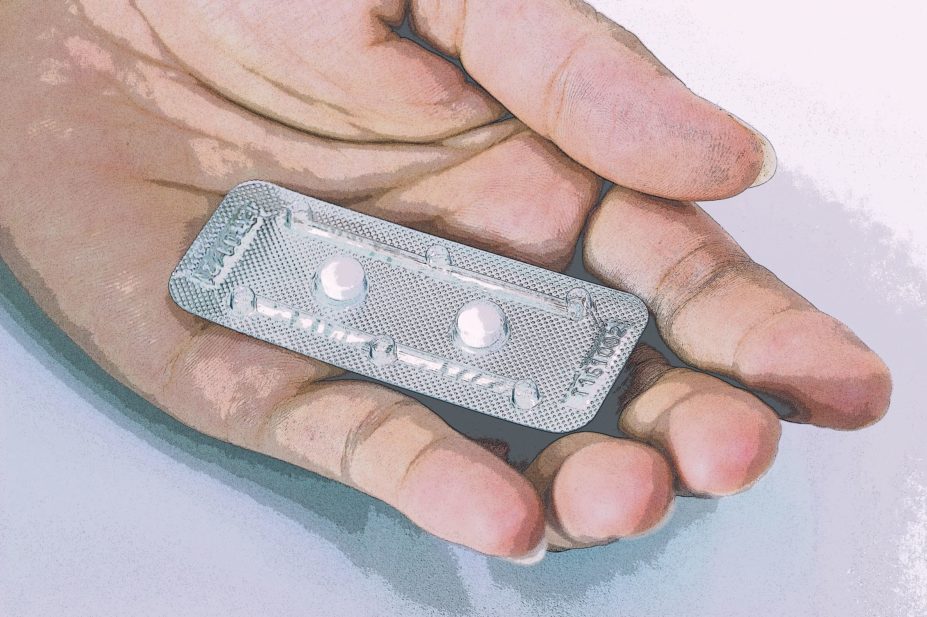

Shutterstock.com

There has been intense media coverage of how Boots responded to a campaign by the British Pregnancy Advisory Service calling on it to lower the price of progestogen-based emergency hormonal contraception (EHC)[1]

. The pharmacy giant claimed to do so would risk “incentivising inappropriate use”, and provoke complaints from those who oppose women using emergency contraception. But although it may have apologised for a “poor choice of words” the offensive principles behind its refusal have underpinned the retail provision of EHC across the pharmacy sector for some time. And women are not having it any more.

Barriers to access

The decision to launch our ‘Just Say Non’ campaign last year — aimed at securing more straightforward, affordable access to EHC from pharmacies for women akin to that in France — was not launched on a whim[2]

. Rather it was borne of frustration after our abject failure to find anyone who could answer what should be a simple question: why was the price of EHC, when sold from a pharmacy in the UK, up to five times higher than that of our European counterparts, where women could often buy it directly from the shelf?

For us, this was not a parlour game or just a matter of intellectual curiosity. As the country’s leading abortion provider, counselling 70,000 women a year with an unplanned pregnancy or a pregnancy they cannot continue, we know that difficulties accessing emergency contraception mean many women do not use it when they need it. These barriers exist at a number of levels: the stigma and shame that is still attached to the ‘morning-after pill’ as a ‘bad girl’s’ drug, the misconceptions that exist about the health risks of this product, difficulties obtaining an appointment, having to undergo a consultation before access can be granted, and, of course, the cost when it is not obtained through an NHS scheme.

What did become clear was that when it came to the cost of the progestogen-based EHC, any quasi normal rules of supply and demand did not apply. When Levonelle was first made available in pharmacies in the early 2000s (‎not, it should be noted, at the behest of the then manufacturer, Schering, but under the orders of the Department of Health) the price was deliberately set high by the company to ensure “that women did not use it as a regular method of contraception”[3]

. It is hard to think of any other product that is priced in accordance with such principles of paternalism — and, in fairness to Boots, it probably thought it was on safe ground parroting such an approach. The medicine would only be available after consultation with a pharmacist.

The UK was a pioneer, one of the first countries to provide women with retail access to emergency hormonal contraception. But other countries quickly surpassed us — recognising that this was an extremely safe medicine which could be sold to women directly and which women could be trusted to use correctly. It became available to buy straight from the shelf in a number of European countries and in North America. As an editorial in the Canadian Medical Association Journal pointed out in 2005: “Why must competent women who have experienced contraceptive failure, a lapse in caution, or sexual coercion or assault be regarded as fair game for unwanted questioning and unsought advice — at their own expense?”[4]

The consultation was eventually dropped, and Plan B — the North American version of Levonelle — became available to buy straight from the shelf.

Unjustifiable premium

We assumed it was the consultation in the UK which added to the cost of the product, so when we launched our campaign last year it was focused on gaining support for the product to shift to general sale list status, in order for some women to avoid paying for a discussion they neither wanted nor needed, as a key means to reduce the price. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society quickly came out against this, arguing that the consultation was free and that the price was high because of the cost of the product itself[5]

.

The cost of the product to pharmacies was falling, while the price it was being sold to women was not

But in fact the cost of the product to pharmacies was falling, while the price it was being sold to women was not. Shortly after we launched the campaign we were informed that generic versions — widely being sold alongside the Levonelle product — were available for the big retailers to buy for just a couple of pounds, yet they were being sold at almost the same price as the branded version. In addition, if the consultation was free, it looks like Boots and others did not get the memo or were happy to keep using the consultation to justify the high price, and indeed have continued to do so in all their public statements to this point. However, other medicines which rightly require a consultation, like sumatriptan (used to treat migraines), to ensure there are no contraindications (of which there are many, while progestogen-based EHC has none of note), are not subject to the same surcharge.

And here is the issue. Does EHC really require “a lot of counselling” for a “correctly supervised sale”? It does not. And such a statement is not far from the condescension that underpinned the Boots letter. This is an extremely safe product, even when used repeatedly and within the same cycle. Repeat use of EHC is classified as Level 1 in the World Health Organization’s Medical Eligibility Criteria[6]

, indicating there should be no restriction on use, and even when it is low cost and easily accessible, this is not how women use it. Why would they?‎

EHC is ineffective if women cannot access it

Pharmacists play a hugely important role in healthcare, and their input should be valued and respected. But it is unclear why, when it comes to EHC, it is held that a mandatory consultation is the only way that valuable contribution can be made. A useful comparison presents itself in the form of nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs). Walk into any large pharmacy today and a bewildering array of products to support efforts to stop smoking are available. Although NRTs can be fatal if ingested in sufficient quantities by children[7]

— the public health benefits of making these products self-selectable clearly outweigh any risks. Having these products on the shelf does not prevent anyone from seeking further advice from a pharmacist about which product would be most suited to their individual needs, nor how they can access more intensive support to help them quit a habit which poses a serious risk to their health.

With a product as safe as EHC, it is absurd that women are only allowed access if they submit to ‘supervision’, which they are also expected to pay for

With a product as safe as EHC which enables women to avoid the considerable health risks posed by an unwanted pregnancy, it is absurd that women are only allowed access if they submit to “supervision”, which they are also expected to pay for.

The discussion around making EHC more accessible is not far off the concerns expressed when at-home pregnancy tests first became available. Could women really be trusted to use these appropriately? What if they misread the results? Surely they needed supervision? ‎ How would they cope at home on learning of a pregnancy? It turned out women, the people who manage monthly bleeds when they are still children, pregnancies, miscarriages, home abortions, childbirth, could manage just fine — as they would if they were allowed to buy lower cost EHC “unsupervised”. We urge pharmacists to support our drive for more accessible EHC and patient-led care—– with support and advice readily available to those who request it and those who do not left alone to purchase a product which gives them a vital second chance of avoiding an unwanted pregnancy in privacy and peace.

Clare Murphy is director of external affairs at the British Pregnancy Advisory Service

How to have effective consultations on contraception in pharmacy

What benefits do long-acting reversible contraceptives offer compared with other available methods?

Community pharmacists can use this summary of the available devices to address misconceptions & provide effective counselling.

Content supported by Bayer

References

[1] Boots apologises following morning after pill row. Pharm J online, 24 July 2017. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20203251

[2] Wilkinson E. Emergency hormonal contraception should be on general sale in the UK, charity urges. Pharm J online, 30 November 2016. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20202024

[3] Pharmacists believe EHC is too costly. Pharm J 3 May 2003. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/pj-online-news-pharmacists-believe-ehc-is-too-costly/20009356.article (accessed August 2017)

[4] Emergency contraception moves behind the counter. Can Med Assoc J 2005;172(7):845. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050260

[5] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Emergency contraception needs a consultaion. November 2016. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/news/details/Emergency-contraception-needs-a-consultation-says-RPS (accessed August 2017)

[6] Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, Fifth edition 2015, World Health Organisation. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/181468/1/9789241549158_eng.pdf (accessed August 2017)

[7] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Nicorette Combi. Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/par/documents/websiteresources/con062829.pdf (accessed 2 August 2017)