Key points:

- Targeting frail older people in their homes led to a predicted potential hospital admissions avoidance of 109 patients in a year.

- The Exeter Cluster Pharmacy (ECP) service demonstrated financial savings of £255,000 in a year by reducing prescribing, social care costs, reducing medication waste and preventing hospital admissions using a team of 2.8 WTE. Taking into account the cost of providing the service, it is estimated that the ECP service delivered an annual saving of approximately £100,000 to the health and social care system.

- Medicines optimisation and patient education in the home can lead to a reduced National Patient Safety Agency risk assessment score of medication-related harm for patients.

- The ECP model enables an initial clinical medication review of the patient by a pharmacist followed by joint working with pharmacy technicians.

- The pharmaceutical interventions led to improvement in patient care, signposting to other health and social care services and helped to improve patients’ quality of life.

Source: Anthony David Baynes / Alamy Stock Photo

The Exeter Cluster Pharmacy (ECP) service, part of Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust, optimises medication for frail older people in their own homes, with the aim of reducing their risk of medication-related harm and preventing unnecessary hospital admission

Introduction

Current pressures on urgent and emergency care in the NHS have led to a focus on new methods for delivering healthcare to patients closer to home[1]

. Of particular interest is how community services can be transformed to help deliver this change to patient-centred care, with the aim of significantly reducing the number of patients being cared for in hospital settings[2]

. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society, the professional membership body for pharmacy in Great Britain, published a report, ‘Now or Never’, in 2013, which proposed that pharmacists could play a vital role in enabling this shift of practice to a community setting[3]

. Pharmacists in primary care can contribute towards keeping people well at home in the long term, through advising and educating patients on their use of medications and by optimising their medication regimes[3]

. This is particularly important to a patient during transitions between healthcare settings (e.g. when they are discharged from hospital to home)[3],

[4]

. In the short term, pharmacists can potentially prevent hospital admissions by intervening when medicines pose an increased risk to the patient at home. The idea of a domiciliary pharmacist is not a new one, but regional and national implementation of this role has been slow[3],

[4],

[5]

.

In 2010, the World Health Organization, a specialised agency of the United Nations concerned with international public health, stated that half of all patients fail to take medicines correctly – the overuse, underuse or misuse of medicines harms people and wastes resources[6]

. A pharmacist is well placed to guide patients on their best use of a medicine, particularly when the annual cost to the NHS of wasted medicines has been estimated at £150m[7]

.

Poor adherence to medicines has been identified as a significant contributing factor to a patient’s sub-optimal use of medicines and wastage[7]

. Some patients do not know how to take their prescribed medicines and need advice and guidance on managing their medicines at home. In the UK, we have an ageing population with many older people being diagnosed with increasingly complex needs[1]

; developing new services focusing on providing pharmaceutical care for older people in their homes could reduce medicines risk and potentially avoid unnecessary hospital admissions. However, patient accessibility to community-based services can often be difficult, particularly for frail older people who may be housebound. One example of specialised community-based pharmacy provision is the Exeter Cluster Pharmacy (ECP) service. The aim of this article is to describe the Exeter model of care and report the findings of a review. This review was designed to gather details of those referred to the service, the pharmaceutical interventions delivered to patients in their homes, their effect on potential hospital admissions, and the impact the service has had on reducing medication-related harm.

ECP service model of care

The ECP service is part of Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust’s community health and social care service, providing a citywide domiciliary pharmacy service to around 145,000 people. The team consists of three band 8a pharmacists – specialist pharmacists with a salary of £39,239–47,088 at the time of the study period – (1.8 whole time equivalent [WTE]), and two technicians (1.0 WTE).

The ECP service optimises medication for frail older people in their own homes, with the aim of reducing their risk of medication-related harm and preventing unnecessary hospital admission. With the patient’s consent, the team have full access to their medical history, including their GP medical notes and prescribed medication, through SystmOne or EMIS Web clinical information systems. Access to this information during the patient consultation allows the team to undertake a level 3 clinical medication review (a face-to-face review of medicines and conditions with the patient[8],

[9]

), including full medicines reconciliation, and to give appropriate health education and advice to the patient in their home, better enabling the patient and/or their carer to manage their medicines at home themselves.

Most referrals to the service come from GPs and the integrated community health and social care team. The pharmacists and technicians delivering the ECP service receive professional support from organisational and national pharmacy networks that ensures appropriate governance, patient safety measures and training are in place. The pharmacy service has been embedded into the referral pathway for the community health and social care services in Exeter for the past nine years.

ECP service in practice

Frail older patients are referred by their GPs and health and social care teams to the ECP service because they have been identified as requiring a medicine review at home. In addition to direct referrals, the pharmacy team also attend monthly ‘virtual ward’ multidisciplinary meetings at GP surgeries to proactively identify additional patients at risk of admission to secondary care or requiring medication support at home. In particular, visits to review vulnerable and frail older people are prioritised by the domiciliary pharmacy service.

Referrals to the service are made via telephone to the health and social care team coordinators, or directly via the service’s generic NHS email account. Pharmacists assess the urgency of the visit request and can review the patient’s medical notes, medication and recent history via smartcard access to the GP clinical information systems (EMIS Web and SystmOne) at their office base. An appointment is then made to visit the patient, often with a representative, in their home (or other preferred setting) by the pharmacist or pharmacy technician. Once a clinical review and case assessment has been completed by a pharmacist, one of the pharmacy technicians may visit the patient, either as a first review meeting or as part of follow-up care, if required.

During a home visit, information is gathered from the patient and/or their carer about the medicines they are actually taking, enabling full medicines reconciliation, a clinical medication review and the identification of any problems with their medicines management to take place. The team is well placed to optimise the patient’s medication following discussion with the patient, GP and carers and to offer advice and education regarding their medication management at home. The service has a range of compliance aids to offer practical support to patients and provide individual medicines reminders or tick charts where appropriate. Following a visit, the patient’s GP is informed and a consultation is recorded on the surgery’s clinical information system, along with the outcome of the visit and any tasks and recommendations for medicines optimisation.

The pharmacy team will also discuss any ongoing needs with carers, nominated community pharmacies, social care, community nursing and mental health practitioners, where appropriate. To provide a more holistic approach to patient care, the team may signpost patients to social services and volunteer organisations who can support them further. The patient is discharged from the service once the episode of pharmaceutical care has been completed.

The ECP service started in September 2006 and has been well received by service users, as evidenced by patient and stakeholder surveys. A comprehensive review of the service was carried out by the team in 2014 to inform the Northern, Eastern and Western Devon clinical commissioning group (CCG) of the impact the service has locally in Exeter, and to guide future service developments in the East Devon locality

Method

A whole-team approach was used to design the evaluation of the service, with advice and guidance sought from the Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust’s clinical effectiveness department. Patient activity data recorded on the trust’s internal database was analysed both retrospectively (February to July 2014) and prospectively (September to December 2014) by the clinical audit facilitator and pharmacists in the team (see online supplementary information for more details). All patients seen by the team during the evaluation periods were included in the review.

The retrospective data from the trust’s internal database was quantitative and lacked the specific clinical information the team sought for their review. The internal activity database included details of referral type and source, and the number and duration of patient visits made, but described little in the way of patient outcomes. To overcome this limitation, a new data collection tool was designed by a trust clinical audit facilitator, and the data for this were collected prospectively (see online supplementary information for more details). This tool also allowed for more comprehensive information to be reviewed, including details about patient demographics, clinical activity and outcomes for the 158 patient contacts made between September and December 2014.

For the purposes of the review, a complex medicines regimen was defined as an individual taking 5 or more medications in multiple frequencies, or more than 12 doses in a day. High-risk medicines were defined as those that have a high risk of causing injury or harm if they are misused or omitted, such as insulin, methotrexate, opioid analgesia and anticoagulants, as per the trust’s policy.

Potential admissions avoided in the retrospective period were assessed by two band 8a pharmacists within the team, using the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) — a UK body that works to improve safety and reduce risks to patients receiving NHS care — risk matrix model[10]

. The risk-scoring methodology from the NPSA uses the likelihood and potential consequence of patient harm to calculate a risk score[11]

.

In this service review, admission avoidance was defined as an intervention that reduced a patient’s risk score from 15–25 (extreme risk) to a risk score of <15. The cases where potential admissions were avoided were further evaluated by two independent pharmacists, a band 8b CCG governance pharmacist and a band 8b lead pharmacist for community services (lead pharmacists with a salary of £45,707–56,504 at the time of the study), who also used the NPSA risk matrix model, and then applied the adapted RiO risk assessment tool[12]

to a randomised sample of patients. Patient and professional stakeholder surveys were also completed from September to November 2014 to assess the view of the service users (see online supplementary information for more details).

Service evaluation results

Over the nine-month combined data analysis period, 346 patients were referred to the ECP service, resulting in a total of 599 patient contacts. The patients referred to, and seen, by the pharmacy service had a range of vulnerabilities, with 57% of patients aged 80 years or over. More than half of those seen were living alone. Around 40% of patients had a care package in place and 61% described themselves as housebound. Of the patient group visited in their homes, 98% had at least one long-term health condition and many had multiple comorbidities. Prospective data analysis demonstrated that four out of five patients were unable to visit their GP or community pharmacy for a medication review at the time of their referral (see online supplementary information for more details).

Patients visited were found to be pharmaceutically complex, with more than half prescribed ten or more medicines; 85% were identified as having an impairment affecting their ability to manage medicines independently (61% had cognitive problems and 55% had a physical impairment). A quarter of the patients had been discharged from hospital within the past eight weeks and a fifth of patients reported that they had experienced a fall recently.

The average time spent on each patient contact was around 120 minutes, including initial preparation time and follow-up activities. The average time spent directly with patients in their home was 43 minutes. After a clinical review by a pharmacist, nearly a third of patients were seen solely by a pharmacy technician, demonstrating the skill mix delivered within the service.

During their home assessments, 58% of patients were found to be taking high-risk medicines and more than half had a complex medicines regimen. The home assessments also identified that 61% of patients visited were not using their medicines as prescribed, half of these also requested further information about their medicines or condition, and 22% were experiencing problems with the pharmaceutical form of medicine or device they had been prescribed.

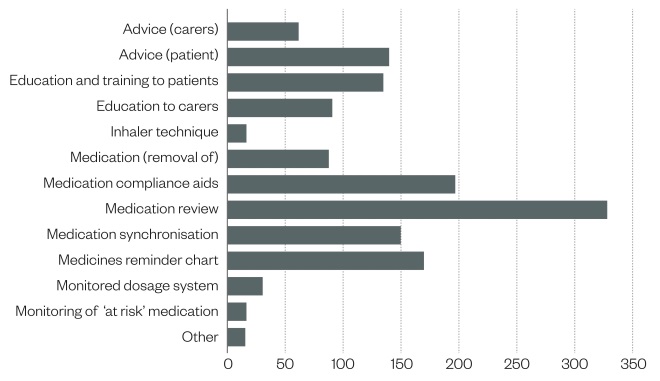

The number of proposed medication changes was recorded over three months as part of the prospective data collection (see online supplementary information for more details). The clinical medication reviews carried out by the team resulted in proposals for medication changes being sent to GPs in 57% of the patients seen. Of these proposals, 79% of the medication changes were fully accepted by the GPs and a further 12% were accepted with modifications. Nearly all patient contacts involved providing information or advice directly to patients or their relatives/carers. Two out of three patient contacts required further actions to be taken, including the preparation of individual medicines reminder charts, resolving problems associated with multi-compartment compliance aids or pill boxes, removal of excess and out-of-date medicines, supply of compliance devices, or arrangement of repeat prescriptions (see ‘Figure 1: Interventions made during patient contact during six-month retrospective review’). During the medicines reconciliation process, 45% of patients identified unwanted medicines and were signposted to local pharmacies to dispose of waste medication appropriately. Non-adherence to medication was assessed during a face-to-face consultation with the patient, as part of the medicines reconciliation process, by recording excess stock in their homes and reviewing their prescription use from GP systems. A large proportion of patient contacts led to the follow-up of medicines-related issues with GPs (78%) and local community pharmacies (56%). Four out of five visits involved dealing with practical problems relating to ordering, obtaining, taking and using medicines correctly.

Figure 1: Interventions made during patient contact (n=441 completed patient contacts) during six-month retrospective review (February to July 2014)

Nearly all patient contacts involved providing information or advice directly to patients or their relatives/carers. Two out of three patient contacts required further actions to be taken, including the preparation of individual medicines reminder charts, resolving problems associated with multi-compartment compliance aids or pill boxes, removal of excess and out-of-date medicines, supply of compliance devices, or arrangement of repeat prescriptions.

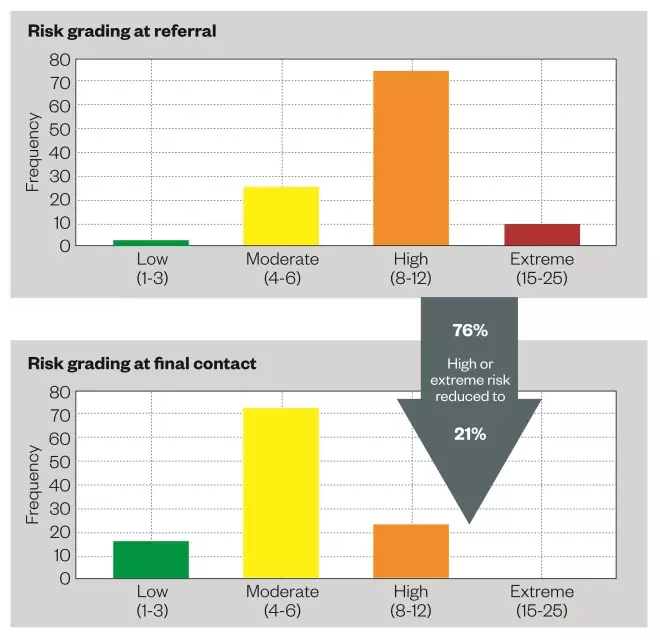

The three-month prospective data collection also evaluated the patient’s risk of medication-related harm in their homes. The level of risk for each patient was assessed by the pharmacy team during home visits by using the NPSA risk assessment tool[10],

[11]

. At point of referral, the patients’ risk of harm from their medicines was shown to be high or extremely high in 76% of patients visited. However, at the final contact with the pharmacy team, the patients’ risk of medication-related harm was reduced to 21% (see ‘Figure 2: Risk score of medication-related harm at initial and final visit’).

Figure 2: Risk score of medication-related harm at initial and final visit

The three-month prospective data collection also evaluated the patient’s risk of medication-related harm in their homes. The level of risk for each patient was assessed by the pharmacy team during home visits using the NPSA risk assessment tool. At point of referral, the patients’ risk of harm from their medicines was shown to be high or extremely high in 76% of patients visited. However, at the final contact with the pharmacy team, the patients’ risk of medication-related harm was reduced to 21%.

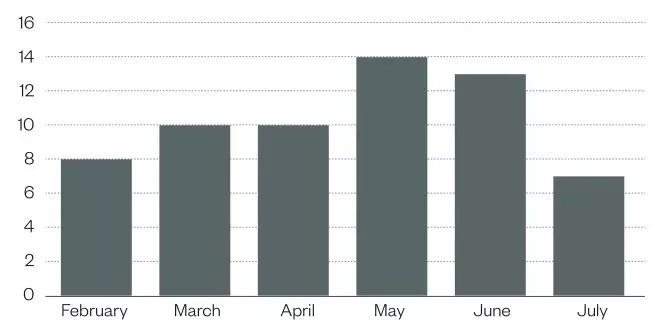

Using patient consultation data collected between February and July 2014, two band 8a pharmacists identified 62 potentially avoidable patient hospital admissions as a result of medicines interventions made by the ECP service (see ‘Figure 3: Admissions avoided during six-month retrospective review’). Two independent pharmacists, one from the local CCG and a lead community services pharmacist (both banded at 8b), then randomly selected and reviewed 20 of these 62 cases. They confirmed the cluster pharmacist’s classification of hospital admission prevention in 85% of these instances by using the NPSA risk matrix[10],

[11]

and adapted RiO risk assessment tool[12]

.

Extrapolation of the 85% agreement figure over a 12-month period suggests that 106 hospital admissions could potentially be avoided. The prospective September to December 2014 data replicated these estimated figures: a total of 32 admissions were classified as avoided, which with an assumed accuracy of 85% indicates that 109 admissions may potentially be avoided each year, following pharmaceutical interventions in a patient’s home environment. The case review by senior pharmacists mirrors the ECP results for potentially avoidable admissions to hospital. The authors acknowledge that there are limitations when interpreting these figures, including possible evaluator bias and the use of non-validated assessment tools.

In the prospective study, changes to medications were proposed in more than two-thirds of patients, on average, the equivalent of two medication changes per patient. Annual cost savings were estimated as £242,642 for hospital admissions potentially avoided, based on an average admission cost of £2,430 to the local acute trust for patients aged over 65 years (2014 data). Further savings of £2,740 in medication costs (reduced prescribing and medicines wastage) and £10,140 related to fewer required social care visits for patients were also calculated, which equated to a £255,504 cost saving by the ECP service, when added together. Taking into account the cost of providing the service, it is estimated that the ECP service delivered an annual saving of approximately £100,000 to the health and social care system, using a staff establishment of 2.8 WTE.

Figure 3: Admissions avoided during six-month retrospective review (n=441 completed patient contacts)

Using patient consultation data collected between February and July 2014, two band 8a pharmacists identified 62 potentially avoidable patient hospital admissions as a result of medicines interventions made by the ECP service.

A survey of health and social care professionals was undertaken between September and November 2014 (see online supplementary information for more details). The team received 119 responses from 313 surveys sent electronically, a 38% response rate. The ECP service was rated positively for its impact on optimising medicines management, maximising the benefits of medication, providing individualised care, and providing safer care. In addition, 93% and 89% of respondents felt that the team had a positive impact on providing cost-effective care and reducing hospital admissions, respectively (see online supplementary information for more details). A survey was also given to each patient seen as part of the service during the same time period, with 66 paper-based surveys handed out. Of these, 38 responses were received (a 58% response rate for this cohort). In the patient survey, 97% of patients felt that consultation with the ECP team had improved their understanding of what their medicines were for, 97% felt the team had improved their knowledge of when and how to take their medicines, and nearly all the patients felt they were now able to manage their medicines better as a result of meeting the pharmacy team at home.

The following case studies highlight the work and impact the ECP service has had for two patients.

Case study one

An 84-year-old female, living alone, was visited by a pharmacy technician to review her use of a new monitored dosage system (blister pack), started by the GP surgery to better enable her to manage her medicines independently. The patient handled the change in medicines management well, and had taken the medication as directed. However, she reported feeling faint and unwell after starting the medicines a week previously. On account of her potential previous non-compliance, the pharmacy technician requested that the GP review her immediately as she was prescribed digoxin 250μg, amiodarone 200mg and bisoprolol 5mg daily. The GP visited the patient that afternoon and reduced her digoxin dose to 125μg daily and requested a digoxin therapeutic level. The medicines prescribed in the blister pack were also amended by the GP and a new supply was arranged. On testing, and as suspected, the patient’s digoxin level was 3.8μg/L (range = 0.5–2.0), her symptoms were therefore likely to be caused by digoxin toxicity. A potential hospital admission was documented as avoided in this instance.

Case study two

An 80-year-old male was referred to the ECP service by his GP, as he was thought to be struggling taking his medicines after being discharged home from hospital. The pharmacist noted that the patient’s medication record held on the GP’s Clinical Information system listed his amiodarone dose at 200mg three times a day, but the hospital discharge letter prescribed an amiodarone reducing dose. The patient was also taking digoxin 125μg once daily and warfarin 5mg daily. At the time of the pharmacist’s visit, the patient was only taking amiodarone 100mg once daily and digoxin and warfarin as prescribed. The patient had not had an international normalised ratio (INR) level taken in the previous fortnight, despite it being reported as 3.6 on his last test. Appointments had been made for the patient to attend the surgery for repeat INR but he had cancelled them as he was temporarily housebound. An urgent INR was requested on that day, returning a value of 6.9. A plan was made with his GP to stop the warfarin until his INR had reduced to an appropriate therapeutic level. During follow-up, digoxin therapeutic levels were also monitored and the GP’s Clinical Information system record for amiodarone dosage was corrected.

Other examples of medication optimisation

- Daily warfarin dose was not being taken safely, so rivaroxaban 15mg daily was prescribed in light of the patient’s renal function, and the switch in medication was managed in their home.

- Pulvinal dry powder inhaler device was replaced by a salbutamol Easi-breathe inhaler, as the patient was unable to use the Pulvinal device appropriately.

- A patient refused to take simvastatin at night and flushed them down the toilet; this was switched to atorvastatin to take in the mornings.

- Buprenorphine 5μg/hour and 10μg/hour patches were stopped, as a patient was still in pain. Alternative therapy of morphine SR capsules 10mg twice daily was given, following a 24-hour washout period, and this was managed in the patient’s home.

- Advice regarding the administration of medicines via a PEG tube for stroke patients was given, and carers were educated on the appropriate and safe administration of medication via this route.

Conclusion

The evaluation of the ECP service identified that the patients referred were predominantly housebound frail older people with a range of comorbidities and who had complex and changing medicines management needs. The team’s referrals and follow-up work demonstrated integrated working within the wider community health and social care service, where a broad range of pharmaceutical interventions were delivered. Patients reported that the education and advice provided by the team improved their ability to care for themselves, demonstrating that the team contributed to maintaining a patient’s independence in their homes. Following discussion with their GPs, a large proportion of patient contacts led to the development of proposals for changes to patients’ medications. The pharmacy team also demonstrated a reduction in risk of medicines-related harm as a result of their visits, and some hospital admissions and their associated costs were potentially avoided. The service review calculated an annual saving of £100,000 to the health and social care system. Development plans are in process in the hope that this model can be extended to serve other localities across Eastern Devon.

The ECP service is well regarded by patients and professional stakeholders alike and it has a positive impact on patient safety. The service review findings support the need to ensure proactive pharmaceutical care is available to the frail older person in their home setting to improve quality of life, save money and reduce medicines wastage.

In February 2014, NHS England issued guidance for commissioners and providers[13]

that describes the need for medicines support for vulnerable older people and highlights a requirement to reduce healthcare-related harm in this patient group. With the ECP service focusing on predominantly housebound older adults with a range of comorbidities, the integrated domiciliary pharmacy service delivers a sustainable means of reducing medication-related risks through the provision of personalised pharmaceutical care.

The most crucial time in the care of frail older people occurs during care transitions and at times of crisis, which can make them vulnerable to problems related to them taking their medication[4],

[14]

. A pharmacy home visit service can optimise a patient’s medication, support them during times of vulnerability and crisis, and enable them to remain at home. The initiative of providing pharmaceutical care in a patient’s home has been implemented in other localities across England, including Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation Trust (Integrated Care Clinical Pharmacist Service), London North West Healthcare (Harrow Integrated Medicines Management Service), Coastal West Sussex CCG[11]

, Lewisham Integrated Medicines Optimisation Service[14]

, and South Downs Health NHS Trust[5]

, with cost savings to the NHS and improvements in patient care at home also being demonstrated with these community service models of care.

Sara Dilks, Kate Emblin and Ian Nash are cluster pharmacists for the Exeter Cluster Pharmacy Service (ECP), Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust, Poltimore Centre, Exeter Community Hospital, Hospital Lane, Exeter, EX1 3RB. Sally Jefferies is senior clinical audit facilitator, Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust, North Devon District Hospital, Suite 1 Chichester House, Raleigh Park, Barnstaple, EX31 4JB. Correspondence to:

sara.dilks@nhs.net

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure:

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements:

The authors are grateful to Susan Nichols for collating information from ComPAS, the Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust community service activity database and to Karena Mulcock from Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust and Gail Foreshew at NEW Devon CCG for reviewing the admissions avoided consultations. The authors would also like to thank Karena Mulcock, Sarah Fowler and Gillie Smith for their comments on the manuscript.

Following the the service evaluation, the ECP service was shortlisted as a finalist in The Health Service Journal Value in Healthcare Awards, in the medicines management category in September 2015. The service was also selected by NHS Providers to exhibit in their Provider Showcase at the November 2015 annual conference. The ECP model has also been presented by poster at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society conference in September 2015 and at the Primary Care Pharmacists Pharmaceutical Network (PCCPN) clinical meeting in October 2015. It was also presented orally at the UKCPA Clinical Pharmacy Autumn Symposium in November 2015.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] NHS England. Urgent and Emergency Care Review Team. Transforming urgent and emergency care services in England. Urgent and Emergency Care Review: End of Phase 1 Report. November 2013. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/keogh-review/Documents/UECR.Ph1Report.FV.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[2] Edwards N. Community services: how they can transform care. King’s Fund, 2014. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/community-services (accessed June 2016).

[3] Smith J, Picton C & Dayan M. Now or never: shaping pharmacy for the future. The report of the Commission on future models of care delivered through pharmacy. Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013. Available at: http://www.rpharms.com/promoting-pharmacy-pdfs/moc-report-full.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[4] Dilks S. The emerging role of the domiciliary pharmacist in Devon. Journal of Integrated Care 2007;15(5):20–25. doi: 10.1108/1 4769018200700035

[5] Stimpson H. Type 3 reviews in Brighton and Hove: a service in development. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2009;282:83–84. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/career/career-feature/type-3-reviews-in-brighton-and-hove-a-service-in-development/10046928.article URI: 10046928

[6] World Health Organization. Medicines: rational use of medicines. Fact sheet No338, May 2010. Available at: http://www.wiredhealthresources.net/resources/NA/WHO-FS_MedicinesRationalUse.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[7] York Health Economics Consortium & The School of Pharmacy, University of London. Evaluation of the scale, causes and costs of waste medicines. November 2010. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/files/90/111804.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[8] Clyne W, Blenkinsopp A & Seal R. A guide to medication review. NPC Plus. 2008. Available at: http://www2.cff.org.br/userfiles/52%20-%20CLYNE%20W%20A%20guide%20to%20medication%20review%202008.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[9] Clinical medication review: a practice guide. NHS Cumbria Medicines Management Team, February 2013. Available at: http://www.cumbria.nhs.uk/ProfessionalZone/MedicinesManagement/Guidelines/MedicationReview-PracticeGuide2011.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[10] National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA). A risk matrix for risk managers. London: NPSA, 2008. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?EntryId45=59833 (accessed June 2016).

[11] Dowell G. Pharmacists can help reduce avoidable hospital admissions in the community. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2013;291:387–388. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/news/pharmacists-can-help-reduce-avoidable-hospital-admissions-in-the-community/11128324.article doi: 10.1211/pj2013.1112832

[12] Croydon Borough Pharmacy Team. NHS Croydon – capturing and analysing clinical interventions. 2012. Available at: www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/upload/documents/Communities/SPS_E_SE_England/Croydon_summary.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[13] NHS England, South. Safe, compassionate care for frail older people using an integrated care pathway: practical guidance for commissioners, providers and nursing, medical and allied health professional leaders. 2014. Available at: http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/safe-comp-care.pdf (accessed June 2016).

[14] Lai K, Howes K, Butterworth C et al. Lewisham Integrated Medicines Optimisation Service: delivering a system-wide coordinated care model to support patients in the management of medicines to retain independence in their own home. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2015;22:98–101. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2014-000565