Shutterstock.com

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Differentiate between primary and secondary headaches, including the subtypes of both;

- Understand clinical assessment of headache and recognise red flag symptoms;

- Know how management strategies differ between headache subtypes and appropriately counsel patients on analgesia use.

Headaches are a common neurological symptom with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 91.3%[1].

Large numbers of patients present to community pharmacies for headache relief without previously seeking advice from a doctor[2,3]. It is therefore necessary that pharmacists provide appropriate guidance and information to patients around headache management and analgesia, as well as signpost patients to onward care as necessary.

This article focuses on effective community pharmacy recognition and management of headache. Recommendations have been adapted from the national headache management system created by the British Association for the Study of Headache (BASH)[4].

Headache types

Headache can be categorised as either primary or secondary. A detailed visual guide of headache types can be found here.

Primary headache

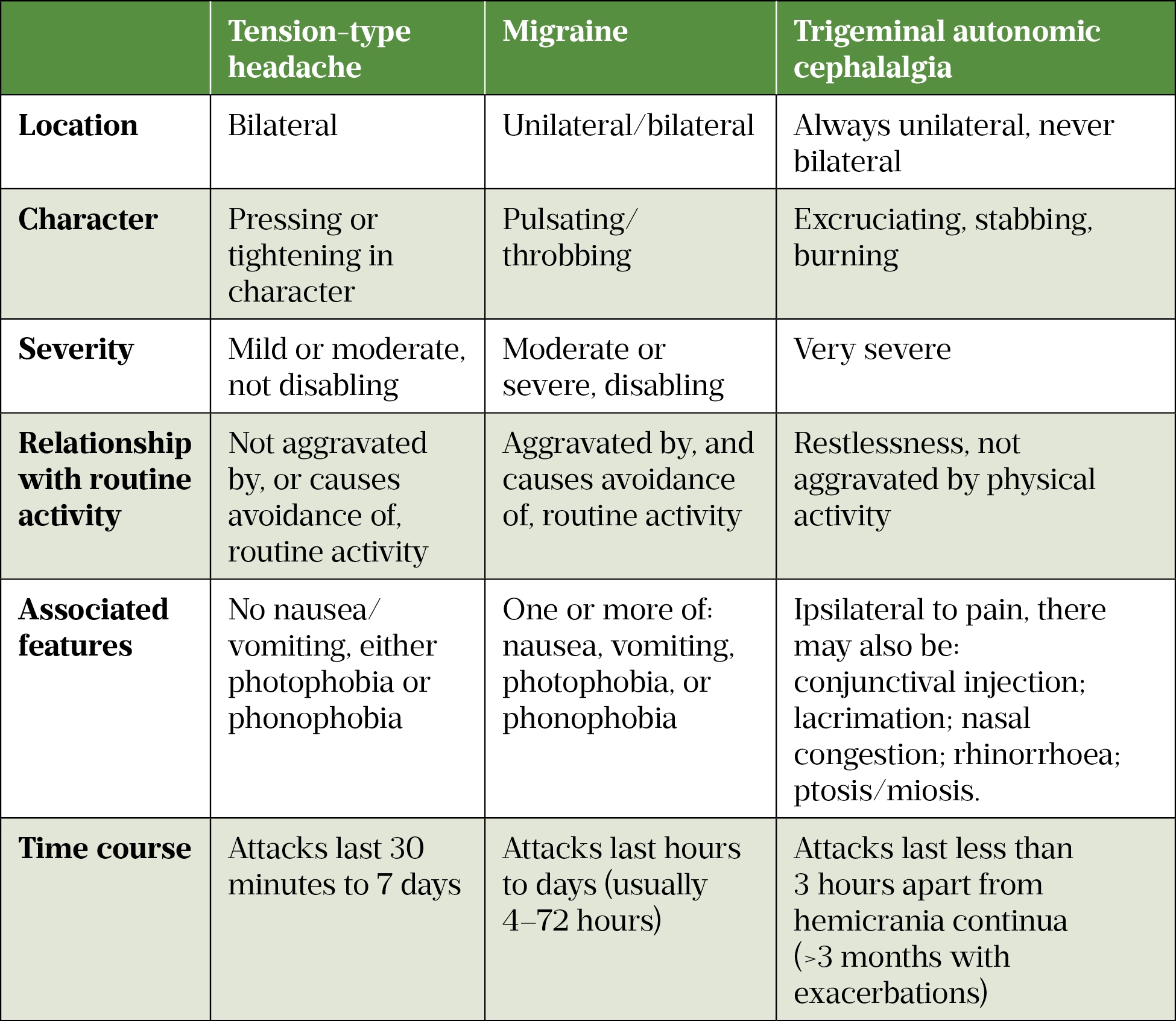

Tension-type headache, migraine and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are types of primary headache, and account for most headache presentations (see Table 1). Patients with primary headache will display normal clinical examination features and no structural lesions on imaging[5]. In contrast, secondary headaches will have an underlying cause.

Tension-type headache is the most common of the primary headache disorders, with a mean lifetime prevalence of 42%[5]. It is non-disabling and usually lasts between 30 minutes and 7 days[6]. Migraine has an average lifetime prevalence of 22% in women and 10% in men[7]. Together, migraine and tension-type headaches affect 2.6 billion people globally[6].

TACs are uncommon headaches with prominent autonomic features including:

- Conjunctival injection and/or lacrimation;

- Nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhoea;

- Eyelid oedema;

- Forehead and facial sweating;

- Miosis and/or ptosis[6,8,9].

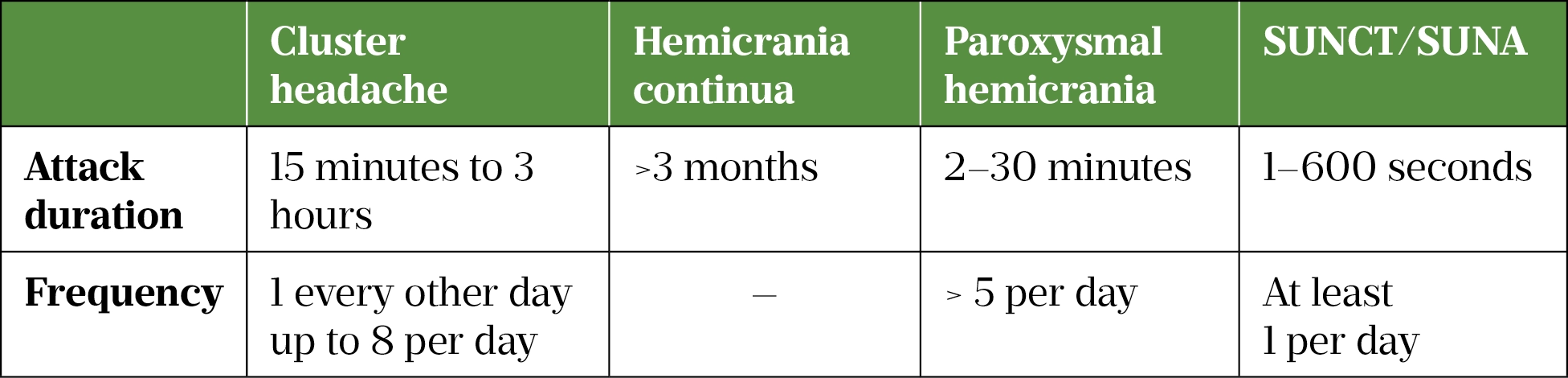

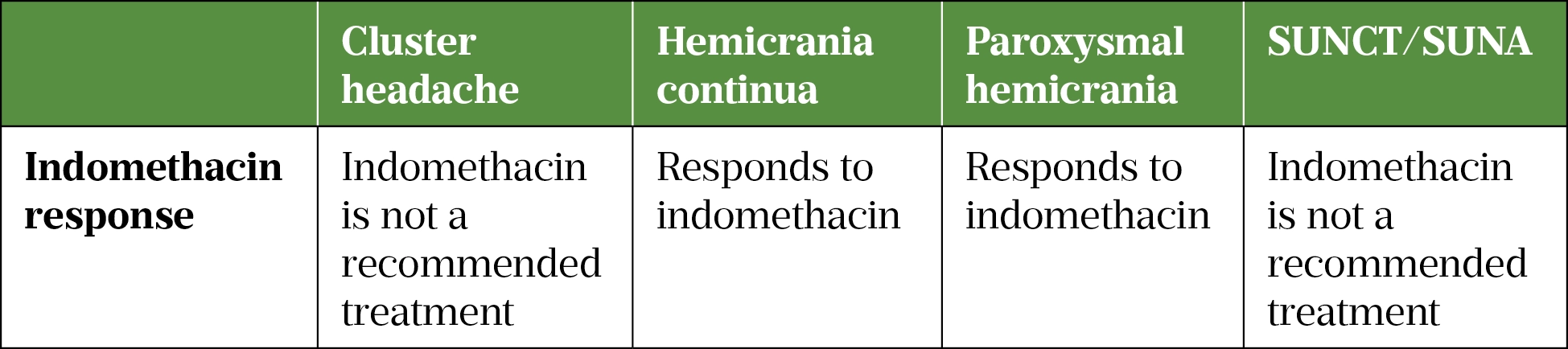

There are four types of TACs, which are differentiated by duration of attack and response to treatment (see Table 2)[6].

Cluster headache has a lifetime prevalence of 0.1%, and hemicrania continua an estimated lifetime prevalence of 0.8–1.5%, although this statistic is debated owing to documented diagnostic inaccuracy in the disorder[9–12]. Paroxysmal hemicrania and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headaches with conjunctival injection, and tearing/short lasting unilateral neuralgiform headaches with cranial autonomic symptom (SUNCT/SUNA) are all very rare[13,14].

Secondary headache

The presence of another pathology is indicative of secondary headache. This can be local (e.g. intracranial/facial structures) or can originate from systemic disease[15–17]. Pathologies include subarachnoid haemorrhage, central nervous system infection, brain tumours and giant cell arteritis[18–21]. However, these are uncommon, accounting for only 2% of all headaches[22]. No clinical features of headache indicate that one secondary cause is more likely than another.

There are four indicators of secondary headache:

- Thunderclap headache (sudden onset headache which reaches maximal intensity within five minutes);

- Associated focal neurological deficit (such as cranial nerve palsies, motor deficits or sensory changes, which may present as changes in special senses, limb or facial muscle weakness, or numbness, respectively);

- Associated systemic features (such as general malaise, fever, and fatigue);

- Patient aged over 50 years, as studies have shown this is an independent risk factor for intracranial pathology regardless of neurological examination findings[23–25].

Clinical assessment

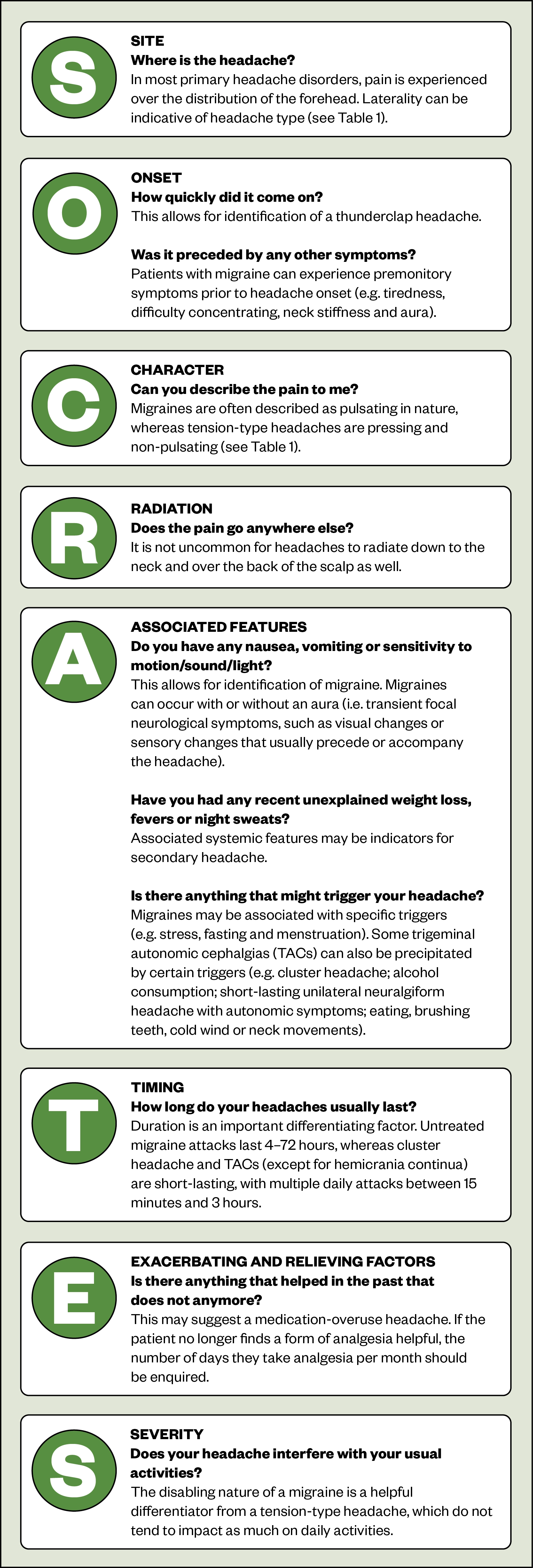

Patient history is essential when establishing a headache diagnosis. SOCRATES is a common mnemonic that can be used as a structure to aid history taking; however, it is worth noting that this is a suggested structure rather than a definitive ‘gold standard’ in history taking:

Red flag symptoms

Patients who present with the following should be referred for medical review:

- Thunderclap headache — requires immediate referral for computerised tomography (CT) scan. It is the most common type of secondary headache, with underlying subarachnoid haemorrhage present in around 19.5–25.0% of cases;

- Focal symptoms (e.g. unilateral limb/facial weakness or sensory changes) or systemic systems (e.g. fever, general malaise or fatigue) with abnormal neurological signs (e.g. hyper- or hypoflexia, loss of muscle power) — significantly increased likelihood of intracranial pathology;

- New type of headache associated with systemic features and/or aged over 50 years — requires referral for a neurological examination[16,18,23,26–28].

A recent, new headache that has evolved over days to weeks and does not present in an episodic fashion is a red flag symptom. Patients should be advised to see their GP for an examination and further investigation, as this may indicate the presence of a space-occupying lesion, such as a brain tumour[23].

Examination

A neurological examination can reassure both the healthcare professional and the patient that there is no underlying pathology. Abnormal neurological signs on examination may be suggestive of secondary intracranial pathology[23].

A brief neurological examination by an appropriately trained clinician (e.g. GP, specialist advanced nurse practitioner or physician assistant) aims to identify abnormal sensation, motor function, cerebellar function, cranial nerves or abnormalities found during fundoscopy[29].

Management

The aims of management are to ease the severity of symptoms and reduce functional impairment, rather than achieve complete cessation of pain.

Migraine therapy is multifaceted and involves acute therapy with basic analgesia and triptans. It is best dealt with through a stratified approach based on headache severity.

When counselling patients, pharmacy teams must educate patients on the correct use of analgesia during an acute attack to prevent medication overuse headache.

The following principles will help guide management:

Previous medication use: determine what medication patients are already using and what they think is effective. This helps identify patients at risk of medication overuse.

Past medical history: Certain comorbidities, such as history of ischaemic heart disease, stroke, myocardial infarction and hypertension severity, are contraindications for triptan therapy[30].

Education: Highlight to patients that primary headaches can be effectively managed with the right treatment. Reassure them that there is no serious cause, explain the natural history of the condition and empower patients to self-manage their condition.

Expectations: Emphasise that the aim of treatment is to reduce severity and functional impairment, rather than a complete cessation of headaches.

Migraine — acute management

The acute management of migraines be approached in two ways:

- A stepped approach, where first-line analgesia is used and stepped up if found to be ineffective;

- A stratified approach, where the treatment is based on attack severity (e.g. if attacks are severely disabling, triptans would be commenced initially rather than basic analgesia). This is the most cost-effective approach[7].

Basic analgesia

Basic analgesia, such as paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are recommended for mild-to-moderate migraine. Opioids are not recommended owing to the high risk of developing medication overuse headache and the risk of withdrawal symptoms on cessation[31,32]. If a treatment is effective. there should be a significant response in two hours (e.g. significant reduction or complete relief of pain)[33]. If this is not the case, an alternative treatment or combination treatment should be considered[34].

Triptans

Triptan therapy should be used if basic analgesia fails, or in severe attacks. Triptans are serotonin receptor (5HT1B/1D) agonists with multiple sites of action[35]. They modulate ascending pain sensory signals and regulate descending signalling in tandem, potentially reducing nociceptive afferent impulses and potentiating descending inhibition of nociception[35].

All triptans should be taken early during an attack, when pain is mild. This significantly improves efficacy of treatment compared to administration when pain is moderate or severe[36]. Almotriptan, eletriptan, frovatriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan and zolmitriptan are all recommended in tablet form[31]. Rizatriptan and zolmitriptan are both available as orodispersers, and sumatriptan and zolmitriptan are available as sprays. Sumatriptan is also available as a 6mg subcutaneous injection; this is the most rapid and effective triptan formulation[4,36].

Choice of triptan will depend on the individual patient, their comorbidities, the pattern of their specific migraines and previously trialled triptans. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network recommend a single dose of 50–100mg oral sumatriptan as an efficacious, safe and cost-effective first-line option[37]. The intranasal spray has identical efficacy and is recommended in patients at risk of vomiting[37].

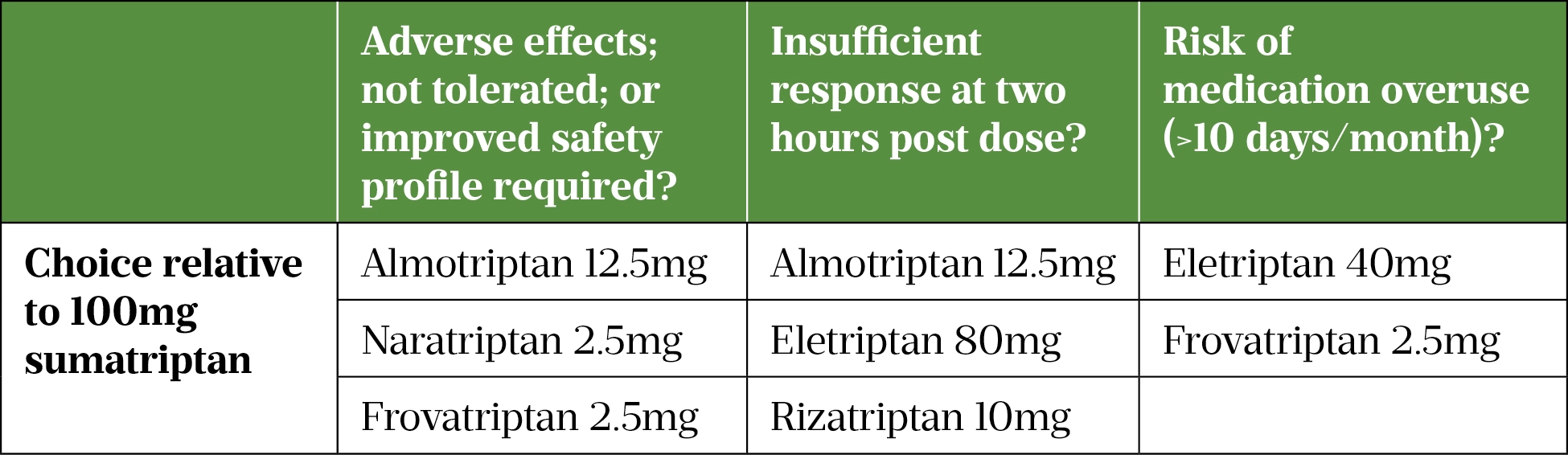

In the case of triptan failure — defined as failure to achieve analgesia during two attacks — switching to an alternative triptan is recommended[31]. Table 3 summarises the recommended alternatives relative to oral sumatriptan 100mg[38–40].

The effectiveness of sumatriptan can be further improved by adding an NSAID with a long half-life (e.g. naproxen)[41]. Anti-emetics (prochlorperazine, domperidone and metoclopramide) are useful adjuncts[42]. However, domperidone and metoclopramide are associated with adverse cardiac and adverse neurological effects, respectively[43,44].

Migraine — preventive treatment

Patients experiencing a migraine four or more times per month should be offered preventive treatments[4]. The drugs below have multiple proposed mechanisms of action, which make them useful prophylactic agents for migraine — independent of their primary indications:

- Amitriptyline: 10–25mg once daily starting dose, titrated in increments of 10–25mg up to a maximum of 150mg/day;

- Candesartan: 2mg once daily starting dose, titrated in increments of 2mg, up to a maximum of 16mg total/day;

- Propranolol: 10mg twice daily, titrated in increments of 10–20mg twice daily up to a maximum of 240mg total/day;

- Topiramate: 25mg once daily, titrated in increments of 25mg, up to a maximum of 200mg total/day[45–51].

There is very little directly comparative data on preventive therapies and so prescribing decisions should be based on individual patient factors, such as previously trialled preventive therapies, concomitant medications that may interact with a preventive therapy and patient comorbidities. For example, propranolol would be contraindicated in an asthmatic patient owing to the risk of precipitating severe bronchospasm.

These medications should be slowly up-titrated to an effective maximum tolerable dose and continued for at least six months and up to one year[52]. For an adequate assessment of effect, the maximum tolerable dose should be continued for six to eight weeks, with evaluation of response to treatment using a headache diary[4]. At its most basic level, it assesses the number, frequency and severity of headaches, as well as analgesics administered. This is not an exhaustive list and patients may use commercially available smartphone apps that record further details about lifestyle habits etc.

For patients who are refractory to initial preventive therapies, injectable treatments can be considered. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies, such as erenumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab, are novel therapies currently available in the UK, which antagonise the action of CGRP (a neurotransmitter responsible for central nociceptive transmission in migraine)[35,53].

Twelve-weekly injections of the muscle relaxant onabotulinumtoxin A is another preventive therapy for patients with chronic migraine (at least 15 headache days per month for more than 3 months, in the absence of medication overuse)[54].

Menstrual migraine

Menstrual migraine occurs between two days before and two days after the first day of menstruation in at least two thirds of menstrual cycles[31]. Acute treatment is the same as for migraines; however, the only triptans recommended are frovatriptan and zolmitriptan owing to proven efficacy[31].

Targeted oestrogen supplementation may be beneficial in menstrual migraine[55]. However, it is contraindicated in migraine with aura owing to increased stroke risk[56].

Medication overuse headache

This occurs in patients with migraine and tension-type headache, who frequently use pharmacotherapy to manage their pain[6]. Medication overuse headache (MOH) often complicates the management of these conditions and is associated with taking triptans or opioids for 10 or more days per month, or standard pain killers for 15 or more days per month[4]. The identification, management and prevention of MOH is an area where pharmacy teams can likely have the biggest impact on patient care.

It is helpful to explain to the patient that restricting use of acute headache medications to no more than two days in a week can help prevent MOH. Treatment for MOH is withdrawal of all analgesia, with no difference in outcome observed between fast or gradual withdrawal[57].

Patient education about the cause and expected course of symptoms following medication withdrawal is a vital aspect of management[58]. It should be explained that improvement can take up to 12 weeks, but that there may be some short-term initial worsening of headache upon withdrawal of the causative medication[31,59]. Reassure patients that withdrawal is likely to improve response to other headache therapies[60].

Tension-type headache

Patients with TTH can be adequately managed with a combination of paracetamol and aspirin, both at a maximum daily dose of 4,000mg[31]. Patients should be reassured that there is no serious underlying cause and that appropriate management with basic analgesia should suffice[31].

There is some evidence to support prevention with acupuncture; however, amitriptyline is the only recommended preventive treatment for TTH that is significantly disabling (interferes with routine activities of daily living)[61]. The starting dose is 10mg once daily, increased in increments of 10–25mg at the discretion of the individual clinician, up to a maximum dose of 150mg[31]. This would likely be over the course of one to two months to observe for a reduction in headache days and severity with a headache diary.

Patient with disabling symptoms should also be clinically assessed to rule out a misdiagnosis of migraine (see Table 1)[55].

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

Management of TACs is determined by response to the NSAID indomethacin, as detailed in Table 4.

Cluster headache

In acute attacks, recommended treatments for cluster headaches are high-flow oxygen, sumatriptan 6–12mg subcutaneous injection or 20–40mg nasal spray, or zolmitriptan 5–15mg nasal spray[31]. Triptans should be used at the onset of an attack, with a maximum daily dose of 12mg subcutaneous sumatriptan, 40mg sumatriptan nasal spray or 15mg zolmitriptan nasal spray[4].

The main preventive therapy is high-dose verapamil, starting at 80mg three times daily and up-titrated by 80mg every 2 weeks to a maximum of 960mg daily[31,62].

An oral corticosteroid at 40mg daily for 10–14 days with subsequent tapering, or greater occipital nerve block with a corticosteroid and/or local anaesthetic injected into the suboccipital region, can be used as interim bridging therapies while longer-term therapy is up-titrated to an effective therapeutic dose[31].

Paroxysmal hemicrania

These attacks are generally too short to respond to acute therapy but are responsive to oral indomethacin at 25mg– 75mg three times daily (the latter dose exceeds the stated maximum dose in the British National Formulary of 200mg per day)[23]. The effect should be rapid; however, some patients may take up to a week to respond. Patients should be counselled on the risks and a clear plan put in place for dose reduction or withdrawal during remission of symptoms. Owing to the potential for peptic ulceration, concomitant prophylaxis with proton pump inhibitors or H2 antagonists is required[31].

Hemicrania continua

Indomethacin for hemicrania continua is also recommended at the same dosage as for paroxysmal hemicrania[4]. Patients with hemicrania continua are also at risk of medication overuse headache[63]. Other analgesics should be withdrawn (as detailed in the medication overuse section) prior to a trial of indomethacin.

SUNCT/SUNA

As with paroxysmal hemicrania, these attacks are too short for acute treatments to be effective. Anticonvulsant therapy is recommended for SUNCT/SUNA; lamotrigine is reported to be most effective, but topiramate, carbamazepine and gabapentin have also been found to relieve symptoms[31].

Summary

Headache disorders are very common and affect a vast proportion of the general population. Pharmacy teams are able to play a vital role in headache care through appropriate identification, patient education and referral. While pharmacists should be vigilant for signs of secondary headache, their most essential role is likely to be working with patients in the use of evidence-based treatment strategies that prevents medication overuse.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ade Williams (superintendent pharmacist, MJ Williams Pharmacy, Bristol), Fayyaz Ahmed (consultant neurologist, Hull Royal Infirmary), Anish Bahra (consultant neurologist, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London) and Alok Tyagi (consultant neurologist, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London) for their help with the conceptualisation of this article.

- 1Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, et al. The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2014;15. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-31

- 2O’Sullivan E, Sweeney B, Mitten E, et al. Headache Management in Community Pharmacies. Ir Med J 2016;109:373.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27685820

- 3Brusa P, Allais G, Scarinzi C, et al. Self-medication for migraine: A nationwide cross-sectional study in Italy. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0211191. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211191

- 4National Headache Management System for Adults. BASH guideline writing committee. 2019.https://www.bash.org.uk/downloads/guidelines2019/01_BASHNationalHeadache_Management_SystemforAdults_2019_guideline_versi.pdf (accessed Dec 2021).

- 5Ferrante T, Manzoni GC, Russo M, et al. Prevalence of tension-type headache in adult general population: the PACE study and review of the literature. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:137–8. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1370-4

- 6Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202

- 7Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Stone AM, et al. Stratified Care vs Step Care Strategies for Migraine. JAMA. 2000;284:2599. doi:10.1001/jama.284.20.2599

- 8Goadsby P. A review of paroxysmal hemicranias, SUNCT syndrome and other short- lasting headaches with autonomic feature, including new cases. Brain. 1997;120:193–209. doi:10.1093/brain/120.1.193

- 9Fischera M, Marziniak M, Gralow I, et al. The Incidence and Prevalence of Cluster Headache: A Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:614–8. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01592.x

- 10Ramón C, Mauri G, Vega J, et al. Diagnostic Distribution of 100 Unilateral, Side-Locked Headaches Consulting a Specialized Clinic. Eur Neurol. 2013;69:289–91. doi:10.1159/000345707

- 11Bigal ME, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ, et al. Primary chronic daily headache and its subtypes in adolescents and adults. Neurology. 2004;63:843–7. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000137039.08724.18

- 12Rossi P, Faroni J, Tassorelli C, et al. Diagnostic Delay and Suboptimal Management in a Referral Population With Hemicrania Continua. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2009;49:227–34. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01260.x

- 13Sjaastad O, Bakketeig LS. The rare, unilateral headaches. Vågå study of headache epidemiology. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:19–27. doi:10.1007/s10194-006-0292-4

- 14Williams MH, Broadley SA. SUNCT and SUNA: Clinical features and medical treatment. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;15:526–34. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2006.09.006

- 15Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT, et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3016–b3016. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3016

- 16Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, et al. Incidental Findings on Brain MRI in the General Population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1821–8. doi:10.1056/nejmoa070972

- 17Katzman GL. Incidental Findings on Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging From 1000 Asymptomatic Volunteers. JAMA. 1999;282:36. doi:10.1001/jama.282.1.36

- 18Morgenstern L, Luna-Gonzales H, Huber J, et al. Worst headache and subarachnoid hemorrhage: prospective, modern computed tomography and spinal fluid analysis. Ann Emerg Med 1998;32:297–304.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9737490

- 19van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, et al. Clinical Features and Prognostic Factors in Adults with Bacterial Meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1849–59. doi:10.1056/nejmoa040845

- 20Hamilton W, Kernick D. Clinical features of primary brain tumours: a case-control study using electronic primary care records. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:695–9.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17761056

- 21van der Geest KSM, Sandovici M, Brouwer E, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Symptoms, Physical Signs, and Laboratory Tests for Giant Cell Arteritis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1295. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3050

- 22Ahmed F. Headache disorders: differentiating and managing the common subtypes. British Journal of Pain. 2012;6:124–32. doi:10.1177/2049463712459691

- 23Locker TE, Thompson C, Rylance J, et al. The Utility of Clinical Features in Patients Presenting With Nontraumatic Headache: An Investigation of Adult Patients Attending an Emergency Department. Headache. 2006;46:954–61. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00448.x

- 24Ramirez-Lassepas M, Espinosa CE, Cicero JJ, et al. Predictors of Intracranial Pathologic Findings in Patients Who Seek Emergency Care Because of Headache. Archives of Neurology. 1997;54:1506–9. doi:10.1001/archneur.1997.00550240058013

- 25Edlow JA, Panagos PD, Godwin SA, et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Acute Headache. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2008;52:407–36. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.001

- 26Linn FHH, Rinkel GJE, Algra A, et al. Headache characteristics in subarachnoid haemorrhage and benign thunderclap headache. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1998;65:791–3. doi:10.1136/jnnp.65.5.791

- 27Landtblom A-M, Fridriksson S, Boivie J, et al. Sudden Onset Headache: A Prospective Study of Features, Incidence and Causes. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:354–60. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00368.x

- 28Linn FHH, Wijdicks EFM, van Gijn J, et al. Prospective study of sentinel headache in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. The Lancet. 1994;344:590–3. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91970-4

- 29Izumi-Richards N, Simon C. Neurological assessment. InnovAiT. 2013;6:405–15. doi:10.1177/1755738013488013

- 30Dodick D, Lipton RB, Martin V, et al. Consensus Statement: Cardiovascular Safety Profile of Triptans (5-HT1B/1D Agonists) in the Acute Treatment of Migraine. Headache. 2004;44:414–25. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04078.x

- 31BASH guidelines 2019. British Association for the Study of Headache. 2019.http://www.bash.org.uk/guidelines/ (accessed Dec 2021).

- 32Limmroth V, Katsarava Z, Fritsche G, et al. Features of medication overuse headache following overuse of different acute headache drugs. Neurology. 2002;59:1011–4. doi:10.1212/wnl.59.7.1011

- 33Edmeads J. Defining Response in Migraine: Which Endpoints Are Important? Eur Neurol. 2005;53:22–8. doi:10.1159/000085038

- 34Dahlöf C. Infrequent or Non-Response to Oral Sumatriptan does not Predict Response to Other Triptans—Review of Four Trials. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:98–106. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01010.x

- 35Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, et al. Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing. Physiological Reviews. 2017;97:553–622. doi:10.1152/physrev.00034.2015

- 36Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA. Sumatriptan (all routes of administration) for acute migraine attacks in adults – overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009108.pub2

- 37Pharmacological management of migraine. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2018.https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1091/sign155.pdf (accessed Dec 2021).

- 38Poolsup N, Leelasangaluk V, Jittangtrong J, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of frovatriptan in acute migraine treatment: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30:521–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2005.00677.x

- 39Evers S, Savi L, Omboni S, et al. Efficacy of frovatriptan as compared to other triptans in migraine with aura. J Headache Pain. 2015;16. doi:10.1186/s10194-015-0514-8

- 40Cortelli P, Allais G, Tullo V, et al. Frovatriptan versus other triptans in the acute treatment of migraine: pooled analysis of three double-blind, randomized, cross-over, multicenter, Italian studies. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:95–8. doi:10.1007/s10072-011-0551-2

- 41Law S, Derry S, Moore RA. Sumatriptan plus naproxen for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008541.pub3

- 42Ross-Lee LM, Eadie MJ, Heazlewood V, et al. Aspirin pharmacokinetics in migraine. The effect of metoclopramide. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;24:777–85. doi:10.1007/bf00607087

- 43Domperidone: risks of cardiac side effects. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2014.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/domperidone-risks-of-cardiac-side-effects (accessed Dec 2021).

- 44Metoclopramide: risk of neurological adverse effects. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2014.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/metoclopramide-risk-of-neurological-adverse-effects (accessed Dec 2021).

- 45Sprenger T, Viana M, Tassorelli C. Current Prophylactic Medications for Migraine and Their Potential Mechanisms of Action. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:313–23. doi:10.1007/s13311-018-0621-8

- 46Ziegler DK. Migraine Prophylaxis. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:486. doi:10.1001/archneur.1987.00520170016015

- 47Jackson JL, Shimeall W, Sessums L, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c5222–c5222. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5222

- 48Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic Treatment of Migraine With an Angiotensin II ReceptorBlocker. JAMA. 2003;289:65. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.65

- 49Stovner LJ, Linde M, Gravdahl GB, et al. A comparative study of candesartan versus propranolol for migraine prophylaxis: A randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, double cross-over study. Cephalalgia. 2013;34:523–32. doi:10.1177/0333102413515348

- 50Linde K, Rossnagel K. Propranolol for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003225.pub2

- 51Guo Y, Han X, Yu T, et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy of topiramate in migraine prophylaxis. Neural Regen Res 2012;7:1806–11. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.23.007

- 52Diener H-C, Agosti R, Allais G, et al. Cessation versus continuation of 6-month migraine preventive therapy with topiramate (PROMPT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2007;6:1054–62. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(07)70272-7

- 53Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies. The Migraine Trust. 2021.https://migrainetrust.org/live-with-migraine/healthcare/treatments/calcitonin-gene-related-peptide-monoclonal-antibodies/2021 (accessed Dec 2021).

- 54Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Chronic Migraine: Pooled Results From the Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phases of the PREEMPT Clinical Program. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2010;50:921–36. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x

- 55MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, et al. Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: A double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology. 2006;67:2159–63. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000249114.52802.55

- 56Kurth T, Slomke MA, Kase CS, et al. Migraine, headache, and the risk of stroke in women: A prospective study. Neurology. 2005;64:1020–6. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000154528.21485.3a

- 57Rossi P, Jensen R, Nappi G, et al. A narrative review on the management of medication overuse headache: the steep road from experience to evidence. J Headache Pain. 2009;10:407–17. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0159-6

- 58Grande RB, Aaseth K, Benth JŠ, et al. Reduction in medication-overuse headache after short information. The Akershus study of chronic headache. European Journal of Neurology. 2010;18:129–37. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03094.x

- 59Mathew NT, Kurman R, Perez F. Drug Induced Refractory Headache – Clinical Features and Management. Headache. 1990;30:634–8. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1990.hed3010634.x

- 60Zeeberg P, Olesen J, Jensen R. Probable medication-overuse headache: The effect of a 2-month drug-free period. Neurology. 2006;66:1894–8. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000217914.30994.bd

- 61Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for tension-type headache. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007587

- 62Leone M, D’Amico D, Frediani F, et al. Verapamil in the prophylaxis of episodic cluster headache: A double-blind study versus placebo. Neurology. 2000;54:1382–5. doi:10.1212/wnl.54.6.1382

- 63Young WB, Silberstein SD. Hemicrania Continua and Symptomatic Medication Overuse. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 1993;33:485–7. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1993.hed3309485.x