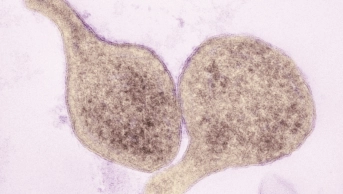

CNRI / Science Photo Library

Syphilis is a multi-stage, multi-system disease caused by Treponema pallidum, a spirochaete bacterium. It is predominantly a sexually transmitted infection (STI), but can also be transmitted congenitally. In 2012, there was an estimated global prevalence of 17 million cases in adults aged 15–49 years, with an incidence of 5.6 million cases. The highest rates of prevalence and incidence are in the World Health Organization (WHO) Africa region[1]

. Treatment with antibiotics early in the onset of the disease is usually effective, but if left untreated it can lead to serious complications.

Epidemiology

While the overall number of STIs diagnosed by sexual health services in the UK fell by 4% from 2015 to 2016, the number of syphilis diagnoses (primary, secondary and early-latent stages) was the largest reported since 1949[2]

. In 2016, there were 5,920 diagnoses of syphilis made in England, compared with 5,281 in 2015 (a rise of 12%). Since 2010, the number of syphilis cases has risen year on year, increasing from from 2,646 cases in 2010 to 5,920 cases in 2016[3]

.

The majority of these diagnoses (n=4,788) were made in men who have sex with men (MSM). Certain behaviours have been associated with an increased risk of bacterial STI transmission, such as chemsex (sexualised recreational drug use)[4]

.

Women accounted for 321 of the 5,920 cases diagnosed in 2016. The increase between 2015 and 2016 was also much lower in women than in men (3% versus 13%). Cases of congenital syphilis can be prevented via appropriate antenatal screening and treatment. An active surveillance system in the UK in 2011–2015 showed a yearly incidence of congenital syphilis below the WHO threshold for elimination of <0.5/1000 live births, with 17 cases reported over the surveillance period[5],[6]

.

Transmission

Most syphilis infections are sexually transmitted via direct contact with an infectious lesion either during sex or through sharing sex toys (acquired). Around a third of sexual contacts with infectious syphilis will go on to develop the disease[7],[8]

. The site of infection is usually the genitals in heterosexual patients but 32–36% of diagnoses in MSM may be at other sites (i.e. oral, rectal and anal)[9]

.

Acquired syphilis is divided into two stages: early and late. The early stage can be subdivided into primary syphilis, secondary syphilis and early-latent syphilis. The late stage can be subdivided into late-latent and tertiary syphilis[10]

.

However, syphilis can also be transmitted congenitally because it readily crosses the placenta. Congenital syphilis is also divided into two stages: early and late. Around two-thirds of infants with congenital syphilis will be asymptomatic at birth but will go on to develop symptoms within five weeks[11],[12]

.

Symptoms

Acquired syphilis

The first symptoms of primary syphilis generally appear after an incubation period of 21 days. Ulcers can appear more quickly with a large infectious dose[10],[13]

. The disease usually starts as a single papule with regional lymphadenopathy. The papule then ulcerates to form a chancre, a painless, indurated skin lesion that is located on the anogenital region. It has a clean base that discharges clear serum. Uncommonly, they can be multiple, painful, extra genital (usually oral) and discharge pus[14]

. Multiple lesions are more common in patients who are co-infected with HIV[15]

. The ulcers usually resolve in 3–8 weeks.

Without treatment, 25% of infected patients will go on to develop systemic symptoms representing secondary syphilis around 4–10 weeks after the initial chancre (ulcer)[16],[17]

. This usually presents as a rash and widespread lymphadenopathy. It is most commonly diffuse, symmetrical, maculopapular, reddish-brown in colour, and involves the trunk and extremities (including the palms and soles). A pustular form can develop[18]

. Mucosal surfaces may become involved, with large grey, highly infectious lesions (known as condylomata lata) developing in warm, moist areas such as the mouth and perineum[9]

. Other symptoms may include: fever, headache, myalgia, weight loss and hair loss. It can also result in hepatitis, glomerulonephritis and splenomegaly. Neurological involvement, including acute meningitis, occurs in 1–2% of patients[16]

. Secondary syphilis resolves in 3–12 weeks, at which point the disease enters the latent stage, defined as early-latent within two years of infection and late-latent thereafter. Around a quarter of patients will experience a recurrence of symptoms during the early-latent stage[17]

.

Around a third of patients will go on to develop tertiary syphilis 20–40 years after initial infection. This is divided into gummatous disease (15% of patients), cardiovascular disease (10%) and late neurological complications (7%). The late complications vary widely and are rarely seen today owing to widespread antibiotic use[17]

.

Congenital syphilis

Common manifestations of early congenital syphilis (first two years of life) include rash, haemorrhagic rhinitis, lymphadenopathy and skeletal abnormalities. Less commonly, condylomata lata, neurological, ocular and haematological involvement can occur. Late congenital syphilis (after two years) occurs owing to chronic inflammation. Manifestations include a saddlenose deformity, Clutton’s joints (i.e. symmetrical joint swelling, most commonly in the knees), deafness and cognitive impairment[19]

.

Diagnosis and investigations

Syphilis can be difficult to diagnose, therefore, in symptomatic individuals; a thorough clinical history and examination is required to distinguish between late-latent, previously treated and non-syphilitic trepanemal infections (e.g. yaws and pinta), which may have the same serological results.

Laboratory diagnosis

A laboratory diagnosis is made through detection of T. pallidum using dark-field microscopy, genetic techniques (polymerase chain reaction [PCR]), or by blood tests in combination with the clinical history. Each of these tests requires specialist equipment and expertise, and may not be widely available.

Dark-field microscopy is a specific technique for diagnosing syphilis when a chancre or condylomata lata are present. This method is not suitable for examining oral lesions, owing to the presence of commensal bacteria with a similar appearance.

PCR is a technique whereby the DNA of T. pallidum can be detected. It is an appropriate test in lesions where the infecting organism would be expected to be located (e.g. chancre)[14]

. Direct fluorescent testing can also be performed on samples from the lesions using antibodies tagged with fluorescein, which attach to specific syphilis proteins.

Blood tests can be divided into non-specific (i.e. non-treponemal) versus specific (i.e. treponemal). While non-specific tests have traditionally been used for screening, newer versions of specific tests have made them easier to use. The British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) guidelines recommend a specific treponemal test as an initial screening tool (EIA, CLIA, TPPA), followed by confirmation with a different treponemal test. A non-specific VRDL/RPR test is done to help stage the infection or determine the need for treatment (e.g. if a patient has previously been treated and has been re-infected). These tests cannot differentiate syphilis from the endemic treponemal diseases (e.g. yaws and pinta)[14]

.

Treatment of syphilis

The choice of treatment is dependent upon the stage and site of infection (see Table 1). Penicillins are the recommended first-line treatment. Primary syphilis may be treated with a single intramuscular injection of benzathine pencillin[14],[20]

. A longer duration is required for those who have had syphilis for more than two years (i.e. late syphilis) because there is an associated risk of relapse after short courses of treatment[21]

. In cases of neurosyphilis, specific treatment is selected based upon cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) penetration resulting in anti-treponemal levels[22]

.

Although penicillins are considered the gold standard, clinical scenarios may occur where this may be inappropriate. For example, cases of allergy; non-adherence; refusal of parenteral therapy; and resource-poor settings. There are several options for patients who are allergic to penicillin. These include, if deemed appropriate, penicillin desensitisation therapy[23]

or alternative treatments (see Table 1). Doxycycline is the preferred alternative in resource-poor settings owing to its low cost and oral administration. Resistance and reported clinical failure limits the use of macrolides (e.g. erythromycin[14]

); these should only be used in settings with resistance testing or in penicillin-allergic patients who are pregnant; however, follow-up must be carried out[24],[25]

. In patients who may not adhere to complex drug regimens, stat doses of azithromycin have demonstrated efficacy in early syphilis[26]

.

When treating pregnant patients, the trimester and staging of disease are important in determining an appropriate treatment regimen, as outlined in Table 1.

| Clinical stage | Recommended regimen | Alternative regimens* |

|---|---|---|

* There are alternative regimens when a recommended regimen is not available or appropriate (e.g. penicillin-allergic patients, parental treatment refused or adherence cannot be ensured); **Follow-up of the child should be ensured to evaluate success of the treatment; ***Steroids should be given with all treatment regimens for late syphilis with cardiovascular or neurological involvement; 40–60mg prednisolone OD for three days starting 24 hours before antibiotics; **** The maximum interval between doses is 14 days. | ||

| Early syphilis (primary, secondary or latent <2 years) in adults | Benzathine penicillin 2.4 MU intramuscularly (IM) as a single dose | Procaine penicillin G 600,000 units IM daily for 10 days Amoxicillin 500mg orally (PO), four times a day (QDS) plus probenecid 500mg for 14 days Penicillin allergic: Doxycycline 100mg PO, twice daily (BD) for 14 days Ceftriaxone 500mg IM daily for 10 days (dependent on allergy) Azithromycin 2g PO stat or azithromycin 500mg daily for 10 days** Erythromycin 500mg QDS for 14 days** |

| Late (late or latent syphilis or syphilis of unknown duration), cardiovascular and gummatous syphilis in adults*** | Benzathine penicillin 2.4 MU IM, given weekly for three weeks (three doses)**** | Procaine penicillin G 600,000 units IM every day (OD) for 14 days Amoxicillin 2g PO, three times daily (TDS) plus probenecid 500mg QDS for 28 days Penicillin allergic: Doxycycline 100mg PO BD for 28 days |

| Neurosyphilis*** | Benzylpenicillin 10.8–14.4g daily, given as 1.8–2.4g intravenously (IV) every 4 hours for 14 days | Amoxicillin 2g PO TDS plus probenecid 500mg PO QDS for 28 days Procaine penicillin G 1.8–2.4 MU IM OD plus probenecid 500mg PO QDS for 14 days Penicillin allergic: Doxycycline 200mg PO BD for 28 days Ceftriaxone 2g IM or IV OD for 10–14 days (dependent on allergy) |

| Syphilis management in pregnancy | ||

| Early syphilis (primary, secondary or latent <2 years) | First and second trimester: Benzathine penicillin 2.4 MU IM single dose Third trimester: Benzathine penicillin 2.4 MU weekly (two doses) | Penicillin non-allergic: Procaine penicillin G 600,000 unit IM daily for 10 days Amoxycillin 500mg PO QDS plus probenecid 500mg PO QDS for 14 days Penicillin allergic: Ceftriaxone 500mg IM daily for 10 days (dependent on allergy) Erythromycin 500mg PO 14 days Azithromycin 500mg PO daily for 10 days** |

| Late syphilis (latent syphilis or syphilis of unknown duration) | Benzathine penicillin 2.4 MU IM given weekly for three weeks (three doses)**** | Procaine penicillin G 600,000 units IM OD for 14 days Amoxycillin 2g PO TDS plus probenecid 500mg QDS for 28 days |

| Congenital syphilis management in neonates | ||

| Congenital syphilis | Benzyl penicillin sodium IV 30mg/kg 12-hourly in the first 7 days of life and 8-hourly thereafter for 10 days | Procaine penicillin 50,000 units/kg daily IM for 10 days |

Treatment side effects

Penicillin use has an associated hypersensitivity risk. Patients may also suffer from a Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction, which manifests as a febrile illness and rash; it is hypothesised that the killed spirochaete releases a causative endotoxin. In cases of cardiovascular and neurosyphilis, steroids are co-administered to prevent atrophy of the corresponding organ by this reaction[20]

. The patient should be aware of this reaction to prevent incorrect labelling as penicillin allergic. On rare occasions, procaine psychosis, an acute psychotic reaction, may occur owing to inadvertent intravenous administration, potentially causing anxiety, hallucinations and convulsions. This can last up to 20 minutes[28]

.

Patient counselling

Patients should be counselled to monitor for these symptoms and should contact a healthcare professional if they occur; they should not resume sexual activity until two weeks after treatment completion or, in the presence of any lesion(s), until all lesions have healed[14],[20]

. Latex condoms may protect against transmission from penile lesions and patients should be advised to sterilise any sex toys; this may be done in a dishwasher. Patients should alert previous sexual partners, who may be tested according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines[29]

. As transmission is only thought to occur in patients where lesions are present, timing of exposure is crucial in determining treatment.

Follow-up and evaluation of syphilis treatment

Patients should be evaluated at six months and one year after treatment using both clinical and serological testing[14]

. Reoccurrence may be attributed to re-infection after adequate treatment. Treatment failure following appropriate antimicrobial therapy is not generally owing to resistance, but rather incomplete therapy or unrecognised CNS infection. Therefore, repeat CSF testing may be indicated[14],[20]

. Management of recurrent infection involves weekly injections of benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM for three doses, unless there is CSF involvement or the patient is penicillin allergic (see Table 1). Those who have recurrent infection should be tested and/or retested for the presence of HIV infection[20]

.

The role of the pharmacist

Pharmacists are ideally placed to advise patients about good sexual health and provide referrals to sexual health services. Box 1 provides more information about the opportunities where pharmacists and the pharmacy team can promote good sexual health, as well as specific advice and counselling points.

Box 1: The role of the pharmacist in the promotion of good sexual health

Pharmacists are ideally placed to advise patients about good sexual health and referrals to sexual health services.

Opportunities to engage with patients include:

- Women requesting emergency contraception:

- Pharmacists should always advise that emergency contraception does not protect against the risks of sexually transmitted infections (STIs);

- Pharmacists should also discuss more appropriate methods of contraception to use in the future.

- Patients requesting products for lesions that could be syphilitic:

- If syphilis cannot be excluded, the patient should be referred to a genitourinary medicine clinic or their GP.

- In hospitals or outpatient clinics:

- Pharmacists should check the appropriateness and duration of therapy and potential interactions, and titrating doses for renal or hepatic impairment;

- Pharmacists should counsel patients on their therapy, discuss any issues with concordance and explain the importance of completing the treatment course and attending follow-up appointments.

Good sexual health is an essential component of the prevention of syphilis. Pharmacists should advise people who are at risk to:

- Always use condoms for vaginal or anal sex;

- For oral sex, cover the penis with a condom, or the female genitals and male/female anus with a latex or polyurethane square;

- Sterilise sex toys after use;

- Get tested for STIs regularly;

- Ensure partners of infected individuals are screened and treated.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 2015;10(12):e0143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304

[2] Public Health England. Sexually transmitted infections and chlamydia screening in England, 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/617025/Health_Protection_Report_STIs_NCSP_2017.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[3] Public Health England. STI diagnoses and rates in England by gender, 2007–2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/626359/2016_Table_1_STI_diagnoses___rates_in_England_by_gender.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[4] Hegazi A, Lee MJ, Whittaker W et al. Chemsex and the city: sexualised substance use in gay bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. Int J STD AIDS 2017;28(4):362–366. doi: 10.1177/0956462416651229

[5] Fenton KA, Mercer CH, McManus S et al. Ethnic variations in sexual behaviour in Great Britain and risk of sexually transmitted infections: a probability survey. Lancet 2005;365(9466):1246–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74813-3

[6] Public Health England. Antenatal screening for infectious diseases in England: summary report for 2013. Health Protect Rep 2014;8:43. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/375211/hpr4314_ntntlscrng.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[7] World Health Organization (WHO). Global guidance on criteria and processes for validation: elimination of mother-to-child transmission (EMTCT) of HIV and syphilis. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112858/1/9789241505888_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accesed March 2018)

[8] Simms I, Tookey PA, Goh BT et al. The incidence of congenital syphilis in the United Kingdom: February 2010 to January 2015. BJOG 2017;124(1):72–77. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13950

[9] Anderson J, Mindel A, Tovey SJ et al. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years’ experience. 3: Diagnosis, treatment, and follow up. Genitourin Med 1989;65:239–243. doi: 10.1136/sti.65.4.239

[10] Hook EW & Marra CM. Acquired syphilis in adults. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1060–1069. doi: 10.1056/nejm199204163261606

[11] Herremans T, Kortbeek L & Notermans DW. A review of diagnostic tests for congenital syphilis in newborns. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;29:495–501. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0900-8

[12] Rawstron S & Hawkes S. Treponema pallidum (syphilis). In: Long S, Pickering L and Prober C (eds) Principles and practice of paediatric infectious diseases. Edinburgh: Elsevier Saunders, 2012.

[13] Magnuson HJ, Thomas EW, Olansky S et al. Inoculation syphilis in human volunteers. Medicine (Baltimore) 1956;35:33–82. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195602000-00002

[14] Kingston M, French P, Higgins S et al. UK national guidelines on the management of syphilis 2015. Int J STD AIDS 2016;27(6):421–446. doi: 10.1177/0956462415624059

[15] Rompalo A, Lawlor J, Seaman P et al. Modification of syphilitic genital ulcer manifestations by coexistent HIV infection. Sex Transm Dis 2001;28:448–454. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200108000-00004

[16] Baughn RE & Musher DM. Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18:205–216. doi: 10.1128/cmr.18.1.205-216.2005

[17] Gjestland T. The Oslo study of untreated syphilis; an epidemiologic investigation of the natural course of the syphilitic infection based upon a re-study of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1955;35(Suppl 34):3–368. (Annex I–LVI). PMID: 13301322

[18] Hicks C & Clement M. Syphilis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations in HIV-uninfected patients. 2017. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/syphilis-epidemiology-pathophysiology-and-clinical-manifestations-in-hiv-uninfected-patients (accessed March 2018)

[19] Fiumara NJ & Lessell S. The stigmata of late congenital syphilis: an analysis of 100 patients. Sex Transm Dis 1983;10:126–129. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198307000-00005

[20] World Health Organization (WHO). WHO guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis). Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/249572/1/9789241549806-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed March 2018)

[21] Dunlop EMC. Survival of treponemes after treatment, comments, clinical conclusions and recommendations. Genitourin Med 1985;61:293–301. doi: 10.1136/sti.61.5.293

[22] Dunlop EM, Al-Egaily SS & Houang ET. Production of treponemicidal concentration of penicillin in cerebrospinal fluid. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;283:646. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6292.646

[23] Chisholm CA, Katz VL, McDonald TL et al. Penicillin desensitization in the treatment of syphilis during pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 1997;14:553–554. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994332

[24] Stamm LV. Global challenge of antibiotic resistant Treponema pallidum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:583–589. doi: 10.1128/aac.01095-09

[25] Zhou P, Li K, Lu H et al. Azithromycin treatment failure among primary and secondary syphilis patients in Shanghai. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:726–729. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e3181e2c753

[26] Hook EW, Behets F, Van Damme K et al. A phase III equivalence trial of azithromycin versus benzathine penicillin for treatment of early syphilis. J Infect Dis 2010;201:1729–1735. doi: 10.1086/652239

[27] Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N et al. 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28(12):1581–1593. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12734

[28] Hedley L & Panesar P. Play your part in managing syphilis. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2012;289:263–266. Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/learning-article/play-your-part-in-managing-syphilis/11106216.article (accessed March 2018)

[29] Workowski KA & Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2010;59(RR12):1–110. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5912a1.htm (accessed March 2018)