Christian Darkin / Science Photo Library

Walk instead of taking the bus. Climb the stairs instead of using the lift. These are well known public health messages that most people associate with improving their cardiovascular health. But the next time you are standing at the bus stop, you might want to think about how you can keep your brain healthy too.

Dementia is fast overtaking cancer as the disease that middle-aged people fear most. With no cure in sight and a sense of fatalism about the condition, people are left feeling helpless in their fight to prevent it. Epidemiologists are now exploring whether changing people’s behaviour can delay or even prevent the onset of disease.

Source: Alzheimer’s Research UK

Simon Ridley, director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, says that trying to disentangle associations that are causal and those that are not is difficult

“I sometimes challenge people when they say dementia is preventable — I tell them it can be preventable,” says Simon Ridley, director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, referring to a body of evidence that suggests some potentially modifiable risk factors can reduce an individual’s risk of developing the disease. “Whatever we say when talking about risk factors, we have to bear in mind that the evidence is not as strong as we’d like it to be. There are always ifs and buts and qualifications, so it’s important to balance a sense of empowerment with realistic expectations.”

Today, about 47 million people around the world have dementia, a disease that robs people of their memory, personality and intellectual functioning, and this number is set to triple to 131 million by 2050. When this tidal wave of disease burden crashes down, it will destabilise economies, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. The cost of care, along with lost productivity of patients and their loved ones, is estimated to be US$818bn a year, more than the annual revenue of Apple (US$742bn), Google (US$368bn), or Exxon (US$357bn).

For the 1% of people with Alzheimer’s disease who have an early-onset, genetic form of the disease, as well as those with genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia, there is no evidence that behaviour modification can lessen an individual’s risk, he says. But for the other 99% of people with Alzheimer’s, and for those with other forms of dementia, such as vascular dementia, there is hope.

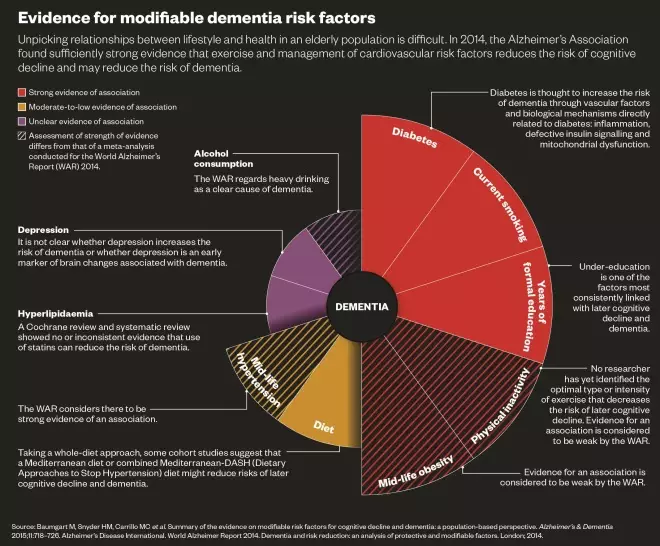

In 2014, the Alzheimer’s Association convened a working group to assess the extent to which people can modify their risk of developing dementia or cognitive decline (see table for summary of evidence). They found “sufficiently strong evidence… to conclude that regular physical activity and management of cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. diabetes, obesity, smoking and hypertension) reduces the risk of cognitive decline and may reduce the risk of dementia”[1]

.

Good for the heart, good for the brain

Although couched in uncertainty given the shortage of studies, other researchers are arriving at similar conclusions. Using data from existing meta-analyses, a UK team showed that up to a third of cases of Alzheimer’s disease worldwide were attributable to seven potentially modifiable risk factors — diabetes, midlife hypertension, midlife obesity, physical inactivity, depression, smoking and low educational attainment[2]

.

The mantra of ‘what’s good for your heart is good for your brain’ is robust enough to get us started

Fiona Matthews, part of the UK team, is an epidemiologist at Newcastle University and programme leader at the MRC Biostatistics Unit in Cambridge. “We’ll still need to understand exactly what’s happening in the third of people whose disease risk might be preventable,” she says, “but in the meantime the mantra of ‘what’s good for your heart is good for your brain’ is robust enough to get us started.”

Different risk factors will likely effect different types of dementia to varying extents, says Ridley. Improvements in cardiovascular health, for instance, could have increased effects on vascular dementia. But the general concept of good cardiovascular health being good for the brain holds true for all types: the brain uses a disproportionately large amount of oxygen and glucose for its size in the body, and any disruption to that supply is bad news. More theoretically, people with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease have trouble clearing the potentially pathogenic amyloid protein from their brain — improvements in perivascular drainage of the protein may therefore help.

Low educational attainment and low physical activity seem to be the most commonly associated risk factors, but discounting any confounding between these and other risk factors is difficult. “The curse of this type of research is trying to disentangle associations that are causal and those that are not,” says Ridley. For most people, randomised controlled trials are the gold standard, but such trials would be unethical if you wanted to assess the effect of smoking, educational attainment or being overweight over the life course.

Kitchen-sink approach

“It may be naive to think that one intervention is going to do it because of the complexity of people’s needs,” adds Ridley. “It’s more than likely that a proverbial ‘kitchen-sink approach’ will be best.”

Such a multimodal, kitchen-sink approach is being tested in the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER). A two-year interim analysis of the study, which randomised more than 1,200 at-risk elderly people to either an intervention group (diet, exercise, cognitive training, vascular risk monitoring) or control group (health advice), showed improvements in cognitive and executive function with the multimodal intervention[3]

.

It will be good in combating the fatalism that surrounds the condition, the idea that nothing can be done to prevent it

If the results prove conclusive over the nine years of the study, it will help stimulate the lacklustre research field in primary prevention for dementia, says Ridley. “It will be good in combating the fatalism that surrounds the condition, the idea that nothing can be done to prevent it. If successful people can go back and unpick the relative importance of each factor. Success can breed success.”

Alzheimer’s Research UK estimates that around 5% of the UK’s dementia portfolio focuses on primary prevention research. It’s a similar proportion to other biomedical disease areas in other high-income countries, but given the comparative underfunding of dementia research compared with economic toll when lined up against diseases such as cancer, researchers are feeling the squeeze.

Even with more funding, research is difficult. Trying to unpick relationships between lifestyle and health in an elderly population is difficult because people in this group often have other things wrong with them. It’s also difficult to quantify an individual’s exposure to every possible risk factor over their entire life course. It’s perhaps even more difficult to persuade a funding body to hand over the cash that will let you attempt this in an entire cohort over 50–60 years.

Evidence could perhaps be pieced together from cohort studies that track trends in prevalence and incidence over time, and link these with changes in public health. In their Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies (CFAS), Matthews and colleagues compared the prevalence of dementia between two generations of people aged 65 years and over in England. They noted a 30% decrease in prevalence, from 7.2% to 6.5%[4]

. “Solid but not spectacular evidence of a decrease,” says Matthews, “but it might support the idea that disease risks can be modified with healthier lifestyles.”

Source: Martin Prince

Martin Prince, a researcher in epidemiology and psychiatry at Kings College London, says that incidence, rather than prevalence, data are more telling of the effect lifestyle changes have on dementia

Policymakers and the media met this 2013 announcement with much enthusiasm, but Martin Prince, a researcher in epidemiology and psychiatry at King’s College London, says such celebrations are “very premature, really”.

At the moment, even within the continent of Europe, the evidence for a decreasing temporal trend in prevalence over the past 20 or 30 years is actually very thin

“At the moment, even within the continent of Europe, the evidence for a decreasing temporal trend in prevalence over the past 20 or 30 years is actually very thin,” he adds.

If the association between improvements in cardiovascular health and decreasing dementia incidence is true, we’d expect to see an increase in prevalence in many low-income and middle-income countries where cardiovascular health is worsening and, says Prince, where such studies have not yet been done. His team have received a grant to look for evidence of trends in Cuba, Peru, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Venezuela and China.

Disease burden

“The problem is that things that improve cardiovascular health may reduce the incidence of dementia,” says Prince, “but they also very plausibly increase survival with dementia, keeping the prevalence — what we’re paying for — roughly the same.” Incidence data, he says, are more telling of the effect lifestyle changes have on the disease, and there are signs of declining trends in incidence in high-income countries. Incidence data from CFAS are under peer review and should be published soon. Prince says the argument is an academic one, with no dispute about the data but disagreements about the inferences that can be drawn.

Nevertheless, he believes the consequences are important. “In my view, looking at the totality of global evidence on prevalence, incidence and survival, if governments and policymakers think that in the future we’re going to need less community care, or less provision in general, and that we’re going to be… saved from the consequences of population ageing by this phenomenon, then that’s really quite an unlikely scenario,” he says.

This note of caution, which Matthews agrees with, was issued in the Alzheimer’s Disease International’s ‘World Alzheimer’s Report 2015’, which Prince co-authored[5]

. The charity nevertheless advocates for more attention to be given to brain health promotion and dementia prevention, joining a chorus of similar recommendations, including those from the Blackfriars Consensus in 2014, which called for governments to focus on dementia risk prevention strategies[6]

.

Unpicking relationships between lifestyle and health in an elderly population is difficult. In 2014, the Alzheimer’s Association found sufficiently strong evidence that exercise and management of cardiovascular risk factors reduces the risk of cognitive decline and may reduce the risk of dementia.

Personal choice versus macro changes

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence working group for dementia, disability and frailty in later life in the UK published its recommendations in October 2015 and came to a similar conclusion about the importance of efforts to change behaviours in midlife[7]

. John Britton, an epidemiologist and director of the UK centre for Tobacco Control Studies at the University of Nottingham, chaired the group.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty about holistic interventions,” he says, referring to ways in which governments can succeed in their efforts to change behaviours. “It’s probably best to concentrate on doing the things that we know work: population-measure interventions to reduce the affordability, availability and accessibility of tobacco and alcohol, and encourage healthy food choices.”

The number of years of formal education has been steadily improving but, he says, the built environment of our cities could be tweaked to encourage people to be more active. “We’re talking about making it safer and easier to walk or cycle to work, or changing the layout of new buildings so that walking up the stairs is the first option over a lift or escalator.”

There is individual responsibility to an extent but to rely on that alone goes quite against the whole history of successful and unsuccessful attempts at behaviour modification

Prince agrees with the need to tackle the problem from a macro level rather than expecting people to make changes themselves. “There is individual responsibility to an extent but to rely on that alone goes quite against the whole history of successful and unsuccessful attempts at behaviour modification,” he says. “Individuals actually need a lot of help and are not necessarily masters of their own destiny. The… state and other actors — food and drink manufacturers and so on — [have a responsibility] to make it easier for people to make the right choices.”

In high-income countries, fear of dementia may be enough to motivate some people into making healthier life choices where warnings of heart health or cancer have fallen short, but this messaging is likely to be less effective in developing countries, Prince says. “Right now, awareness [of dementia] is very low in low-income countries so telling people that they’re not going to get a condition that they don’t know about is probably not going to be so impactful,” he says. “Improving awareness of dementia ought to be a public health priority in all of those regions.”

With the inevitable lag between public health efforts and demonstrable results, worldwide improvements in modifiable risk factors, says Prince, “are unlikely to make much of a dent on the current projections [of dementia’s future disease burden]”. Should we not, then, focus all our attention and research funding on trying to find a treatment? “Not at all,” says Prince, “if we don’t push forward with primary prevention then the projections are only going to get even worse.”

References

[1] Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC et al. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspective. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2015;11:718–726. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.016

[2] Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE et al. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurology 2014;13:788–794. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X

[3] Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2015;385:2255–2263. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5

[4] Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE et al. A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. The Lancet 2013;382:1405–1412. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61570-6

[5] Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London; 2015.

[6] Lincoln P, Fenton K, Alessi C et al. The Blackfriars Consensus on brain health and dementia. The Lancet 2014;383:1805–1806. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60758-3

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia, disability and frailty in later life – mid-life approaches to delay or prevent onset. NICE guidelines NG16. London; 2015.