Self Portrait 15 painted 27 June 1991 from Self Portrait Series by Bryan Charnley. © James Charnley

The first thing university student Sarah Galloway noticed was that she was tired all the time. Then things got scary. “I became quite violent, tried to harm myself, attack my brother,” she says. She was sectioned and put on antipsychotic drugs. And that would have been the end of it, except that she happened to qualify for a research trial of a new assay for autoantibodies — antibodies that attack the body’s own proteins. Nobody expected the test to come back positive, but it did, for antibodies against a key brain protein: the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) neurotransmitter receptor.

Sarah Galloway was found to have autoantibodies against a key brain protein, and this appeared to underly her psychosis

Galloway was given treatment to dampen down her immune system while she continued taking antipsychotics. “There was a dramatic increase in function,” she says. After taking two years out, she was able to go back to University of Oxford and finish her degree in chemistry.

Probably the most famous case of psychosis caused by NMDA receptor (NMDAR) autoantibodies is that of journalist Susannah Cahalan, described in her memoir Brain on Fire, which is being turned into a Hollywood film. In 2009, Cahalan was initially given a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder but then started having seizures. This caught the attention of neurologists, who eventually diagnosed her with autoimmune-induced brain inflammation, or encephalitis.

But Galloway had no such tell-tale symptoms to alert her doctors to what was going on. “I was really lucky,” she acknowledges.

Schizophrenia isn’t just one disease, but likely multiple diseases with overlapping signs and symptoms

Brian Miller, a psychiatry researcher at Augusta University in Georgia, says current drugs for psychosis all share the same mechanism of action

Psychiatrists have long suspected that the symptoms of schizophrenia have many different causes. Indeed, when Eugen Bleuler coined the term in 1911, he referred to the ‘group of schizophrenias’. “Schizophrenia isn’t just one disease, but likely multiple diseases with overlapping signs and symptoms,” says Brian Miller, a psychiatry researcher at Augusta University in Georgia.

Even so, all the drugs that have been approved to treat psychosis share the same basic mechanism of action: they block the dopamine D2 receptor. Miller contrasts this with other chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure, in which “treatment involves multiple medications with different mechanisms of action, tailored — to some extent — to the individual patient”.

There is a need for new approaches. Schizophrenia affects more than 21 million people worldwide and puts sufferers at risk of unemployment and, more worryingly, suicide. And current antipsychotics are not very effective.

Tom Pollak, a clinical research training fellow at King’s College London who specialises in autoimmunity and psychosis, says that schizophrenia is reminiscent of autoimmune conditions such as multiple sclerosis

The first antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1954. It is still in use today. It was not until 1989 that the FDA approved clozapine, the first of a new generation of antipsychotics designed to have fewer side effects. But in reality, both generations of antipsychotics seem to have similar, often highly debilitating, side effects, including problems with movement and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. And none of them are very good at treating the so-called ‘negative symptoms’ of schizophrenia, such as a lack of emotion, withdrawal from society and low drive. As a result, “a lot of patients don’t like taking them”, says Tom Pollak, a clinical research training fellow at King’s College London who specialises in autoimmunity and psychosis.

The most pressing need is that one-third of patients don’t respond to treatment

In many patients, antipsychotics do not work at all. “The most pressing need is that one-third of patients don’t respond to treatment,” Pollak says.

Prime suspect

In an attempt to find new approaches to treating psychosis, many researchers are turning to the immune system, a suspect that turns up a lot at the schizophrenia crime scene.

For a start, there is a link between being born in winter and being at higher risk for the disease. “[That is] when you’re more likely to have infections,” Pollak points out. There is also an unusual association between owning a cat as a child and going on to develop schizophrenia. This seems strange until you realise that cat faeces carry Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that causes an often silent infection in humans. And a recent large genome-wide study looking at genes associated with schizophrenia found several that are involved in immunity[1]

.

Golam Khandaker, a clinical lecturer in psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, says that inflammatory markers may have a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia

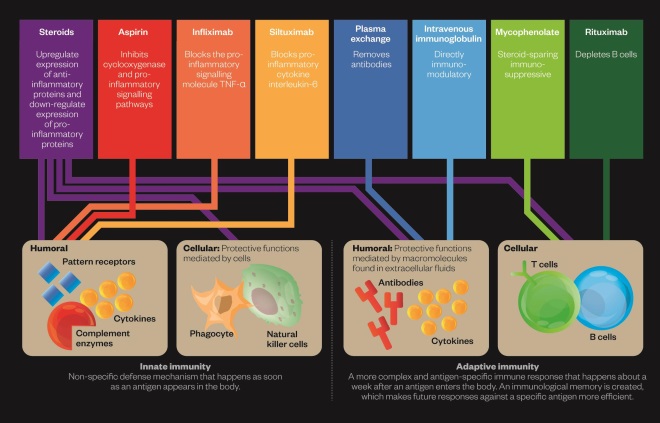

One way of thinking about the role of immunity in schizophrenia is to look at the innate versus the adaptive immune system. Both systems seem to be involved, although not necessarily in the same patients. The innate immune system is a non-specific defence from infection and triggers inflammation. “Since a range of infections have been associated with schizophrenia, it has been suggested that there is a common underlying mechanism, which may be the activation of the innate immune response,” says Golam Khandaker, a clinical lecturer in psychiatry at the University of Cambridge.

The study was able to demonstrate that inflammatory markers may have a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, rather than merely being a consequence of illness or stress

In 2014, Khandaker and colleagues published the results of a longitudinal study, which showed that raised inflammatory markers (interleukin [IL]-6 and C-reactive protein [CRP]) in children was associated with higher rates of depression and psychosis as young adults[2]

. “The study was able to demonstrate that inflammatory markers may have a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, rather than merely being a consequence of illness or stress,” Khandaker says.

Oliver Howes, head of psychiatric imaging at Imperial College London, says that drugs to reduce microglial activation could be a new way of treating psychosis

A study published in 2015 showed that people with schizophrenia have more active microglia — the brain’s main immune cells — than do healthy controls[3]

. Levels of microglial activation were also raised in people deemed to be at high risk of developing schizophrenia. What’s more, the greater the activation, the worse the symptoms were likely to be. “This suggests that treatments to reduce microglial activation could be a new way of treating and even preventing psychosis,” says Oliver Howes, head of psychiatric imaging at Imperial College London and one of the study’s authors.

There is some evidence that anti-inflammatory treatments can be effective in schizophrenia. One meta-analysis from 2014 found that three anti-inflammatory treatments, including aspirin, had a significant effect on the severity of symptoms (as measured on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale) across 26 randomised, controlled trials[4]

. But many other anti-inflammatory agents did not have a significant effect, and the authors point out that the effective treatments have broad activity, so the improvements may not be due to their anti-inflammatory effects.

If some patients have inflammation, why are the results of anti-inflammatory trials not more convincing? A 2013 study of depression, in which inflammation has also been proposed to play a part, may point to an answer[5]

. The study looked at the effects of using infliximab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks a pro-inflammatory signalling molecule, TNF-α. “It was helpful for patients who had elevated levels of CRP before starting treatment, but not for those with normal CRP,” says Khandaker, who did not work on the study.

Miller agrees that treating patients with evidence of inflammation is a helpful approach. His team has completed a small open-label trial of tocilzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-6 receptor. The results are promising and the team has been granted funding for a randomised, controlled trial of siltuximab, a monoclonal antibody which directly blocks IL-6.

Miller does use anti-inflammatories in the clinic for patients who do not respond to conventional treatments and have raised levels of inflammatory markers. But until more convincing results come in, anti-inflammatory drugs will not be licensed to treat schizophrenia. Howes believes this could take four or five years.

Maladaptive immunity

In contrast to the scattergun approach of innate immunity, the adaptive immune system responds in a tailored way to pathogens, generating a long-term immunological ‘memory’, including in the form of antibodies. When the body mistakes its own proteins for invaders, you get autoimmune disease. In some patients, including Sarah Galloway, this seems to underlie their psychosis.

Pollak says that schizophrenia does look a bit like an autoimmune disease. He breaks it down like this: “25% of people with a first episode of psychosis just get better and don’t have symptoms again, 25% have a very progressive, very disabling version of the illness, and 50% have a relapsing–remitting course with reasonable function in between episodes.” He believes this is reminiscent of conditions such as multiple sclerosis. “From a clinical point of view, bells ring there.”

There are antibodies to brain-channel-associated proteins that can cause symptoms that look like schizophrenia initially

Michael Zandi, a neurologist at the University of Cambridge, says that most neurologists and psychiatrists are now referring patients to each other

The first clue that autoimmunity may have a role in schizophrenia came in 2001, when neuroimmunologist Angela Vincent’s team at the University of Oxford identified two patients with autoantibodies to a voltage-gated potassium channel (VGKC) complex who presented with encephalitis[6]

. One of the patients had auditory and visual hallucinations. “[Vincent] found that there are antibodies to brain-channel-associated proteins that can cause symptoms that look like schizophrenia initially,” says Michael Zandi, a neurologist at the University of Cambridge.

In 2007, Josep Dalmau, a neuroimmunologist at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Barcelona, identified a group of patients who had antibodies to the NMDAR[7]

. These patients also had “behavioural changes, delusions, hallucinations. [It] looked like the beginning of schizophrenia,” says Zandi. But then, “they’d go on to have seizures, coma and rhythmic movements”.

However, other researchers, including Zandi, have since identified patients who, like Galloway (who is not one of his patients), do not have the typical features of encephalitis, such as seizures. These patients present with predominantly psychiatric symptoms but have autoantibodies in their blood.

Zandi’s group tested the blood of 46 patients who presented with a first episode of psychosis, and found that three patients (6.5%) were positive for autoantibodies to VGKC or NMDAR[8]

. The autoantibody-positive group of patients appeared to be clinically indistinguishable from those who tested negative. “If you’ve got someone like that and you don’t think they have encephalitis, we don’t know what to do with them,” Zandi says. “Some would treat them with immune treatments. Some would say there’s not enough evidence for that.” He and others are currently designing a clinical trial to fill this gap in the evidence, in the hope that more patients like Galloway can benefit from immune treatments such as steroids and plasma exchange. Galloway has also been given mycophenolate, traditionally used as an immunosuppressant in rheumatoid arthritis, and her doctors are currently applying for funding for the monoclonal antibody rituximab.

Modulating the immune response

Editorial advisers: Golam Khandaker and Michael Zandi, University of Cambridge

Both the innate and adaptive immune systems may be involved in schizophrenia and drugs to target these are being investigated in clinical trials or in individual patients.

Joined-up thinking

Genes are also part of the story, as schizophrenia is known to be highly heritable. Where one identical twin has schizophrenia, there is an almost 50% chance that its twin will have it too. It seems likely that certain genes predispose people to react to an environmental insult in a damaging way.

If you have an autoimmune disease, you’re significantly more likely to develop psychosis, and vice versa

For inflammation, “the theory is that some people have an overactive innate immune system where you’ve got this grumbling level of inflammation, and that accelerates what is the primary problem”, explains Zandi. And some people seem to be genetically at higher risk for developing autoimmune diseases. “If you have an autoimmune disease, you’re significantly more likely to develop psychosis, and vice versa,” says Pollak.

As the complexities of schizophrenia come into focus, it will be important for neurologists and psychiatrists to work together. Galloway has experienced this need first hand. “There is almost a tension between the psychiatric side and the neurological side — they’re not quite connected,” she says. Zandi thinks this is changing. “Most neurologists and psychiatrists are sharing patients and referring patients to each other,” he says.

Since a third of patients do not respond to conventional treatments, ultimately, as Galloway says, “the real issue is to treat people who need treatment with the right treatment”.

References

[1] Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595

[2] Khandaker GM, Pearson RM, Zammit S et al. Association of serum interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein in childhood with depression and psychosis in young adult life: a population-based longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:1121–1128. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1332

[3] Bloomfield PS, Selvaraj S, Veronese M et al. Microglial activity in people at ultra high risk of psychosis and in schizophrenia: an [11C]PBR28 PET brain imaging study. The American Journal of Psychiatry 2016;173:44–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101358

[4] Sommer IE, Van Westrhenen R, Begemann MJH et al. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory agents to improve symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: an update. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2014;40:181–191. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt139

[5] Raison CL, Rutherford RE, Woolwine BJ et al. A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: the role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:31–41. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.4

[6] Buckley C, Oger J, Clover L et al. Potassium channel antibodies in two patients with reversible limbic encephalitis. Annals of Neurology 2001;50:73–78. PMID: 11456313

[7] Dalmau J, Tüzün E, Wu HY et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Annals of Neurology 2007;61:25–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.21050

[8] Zandi MS, Irani SR, Lang B et al. Disease-relevant autoantibodies in first episode schizophrenia. Journal of Neurology 2011;258:686–688. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5788-9