Brain light / Alamy Stock Photo

In 2004, Cathryn Kemp was struck down overnight with acute-on-chronic pancreatitis. By 2010 she had developed a full-blown addiction to opioids.

Following her diagnosis, Kemp’s life turned into an endless cycle of unpredictable episodes of extreme pain, trips to accident and emergency and drawn-out hospital stays. On the rare occasions that she was allowed to go home, she was bed bound, waiting in constant fear for the next cycle to begin. Throughout this time she was prescribed opioids to deal with the pain — either a morphine drip when in hospital or, oxycodone and tramadol when at home.

Opioids, which also include illegal substances such as such as heroin and fentanyl derivatives, are associated with a significant potential for misuse and physical dependence.

Kemp was eventually referred to a London-based specialist who diagnosed her with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, a condition that affects the circular muscle that controls drainage from the bile and pancreatic ducts. With the diagnosis, surgeons were able to carry out a surgical procedure in an attempt to prevent her acute pain episodes. But Kemp had already developed a physical dependence on her pain relief medication.

“I left hospital basically a heroin addict,” says Kemp. “I was addicted to morphine because I’d been on it for four years.”

Despite this, however, Kemp was given a repeat prescription for fentanyl, which is a 100-150 times more potent than oral morphine, in the form of 200mg lozenges and 100mg patches, to deal with breakthrough pain.

She was told to take a maximum of eight fentanyl lozenges a day. However, after three months, and following a harrowing break up, she decided to take an extra lozenge. Within two years, Kemp had spiralled into extreme addiction and was taking 60 fentanyl lozenges every day.

Courtesy of Cathryn Kemp

In 2004, Cathryn Kemp was struck down overnight with acute-on-chronic pancreatitis, six years later she had developed a full-blown addiction to opioids: “I was completely out of control and completely alone with it and my GP was as well,” she says.

“I was completely out of control and completely alone with it and my GP was as well,” says Kemp.

“It took until January 2010 for [my GP] to turn around and say ‘I just can’t do this anymore’. We both knew by then I was taking a fatal dose every day — I knew I was going to die.”

In February of that year Kemp checked in to a five-week rehabiliation progamme at a private clinic, where she was able to completely come off the opioid medications — and she has been off them ever since.

The bigger picture

In 2015, the annual European Drug Report recorded 330,445 high-risk opioid users in the UK, the highest number in Europe[1]

. According to the Public Health Research Consortium, the proportion of patients on the Clinical Practice Research Datalink prescribed opioids doubled between 2000 and 2012, and the length of continuous prescribing periods increased from 64 days to a peak of 102 days in 2013 and 2014. In addition to this, NHS Digital figures show that, in England, the number of patients admitted to hospital for overdosing on opioid painkillers almost doubled between 2005–2006 and 2016–2017.

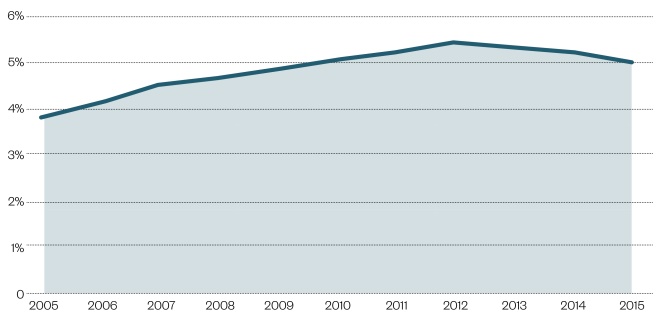

Figure 1: Percentage of patients prescribed opioids in the UK, 2000–2015

Source: Prescribing patterns in dependence forming medicines. 2017. Public Health Research Consortium

The percentage of patients prescribed opioids in the UK doubled between 2000 and 2012, peaking at 5.4% in 2012. Since 2012, there is evidence of a slight decline in opioid prescribing.

Statistics from the Office for National Statistics, 2016, show that there were 58 deaths involving fentanyl and 75 deaths involving oxycodone in England and Wales compared with 34 and 51 deaths respectively registered in 2015[2]

. The number of drug-related deaths involving tramadol fell by 12% from 208 deaths registered in 2015 to 184 deaths in 2016, which may be explained by the fact that tramadol has been controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 as a class C substance since June 2014.

In the United States, President Donald Trump declared the country’s opioid misuse epidemic a public health emergency following an interim report from the Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, published in August last year. It is estimated there are 142 opioid-related deaths in the United States every day.

However, despite evidence suggesting prescription opioid misuse in the UK could reach the crisis levels of the US, Harry Shapiro, director of DrugWise, an online drug information service and a member of the opioid dependency alliance, says the likelihood of that is low.

“America is a very stark situation,” he says.

“For long periods the US was very opioid-phobic and then it realised it could prescribe strong painkillers for non-malignant pain and that is where the problems began.

The situation in this country [UK] is different, the healthcare systems are different — you don’t have people charging you money for prescriptions unless you go private

“The situation in this country [UK] is different, the healthcare systems are different — you don’t have people charging you money for prescriptions unless you go private,” he adds.

Barry Miller, dean of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and a consultant in pain management and anaesthetics, agrees that the situation in the US is very different and attributes this partly to the fact that pharmaceutical companies have never had the same influence in the UK as they do in the US. He says that “stringent changes” in the UK mean that the overall interaction opioid manufacturers have with healthcare professionals and decision makers has substantially fallen.

“But I’m not sure they ever had the influence here that they appear to have had in the US,” he says, where pharmaceutical companies have been widely reported to shower politicians with substantial donations in an attempt to influence drug legislation.

Shapiro says the increase in opioid use seen in the UK is simply a reflection of increased levels of pain across the population and also, to some extent, due to a cohort of people who take opioids not just for pain but to deal with day to day life.

“They make life fuzzy around the edges which is what a lot of people want,” he says.

Miller points out that the number of admissions to hospital for opioid overdoses in the UK has stabilised over the last two or three years and the peak seen in prescribing data in 2012 has seen a small reduction. He believes this could be attributed to an increased awareness through reporting in the press and work being carried out by the Faculty and other pain organisations, and charities to educate prescribers around opioids, how they should be prescribed and the doses that should be considered.

But, he warns, the situation in the UK should not be underestimated.

“We need to keep a careful eye on this and continue to get the message out,” he says.

Assessing and minimising risk

Miller believes that one of the key issues is that there is very little education in any healthcare system about how to use analgesics safely and appropriately.

“Over the last 20 years, it’s become more acceptable to prescribe opioids,” he says.

Opioids are seen as a very useful means of solving short and intermediate term pain problems that have probably led to their longer term use without any therapeutic value

“They are seen as a very useful means of solving short and intermediate term pain problems that have probably led to their longer term use without any therapeutic value and with significant side effects,” he adds.

A report, written by Shapiro, for the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Prescribed Medicine Dependency in 2015, describes the subject of opioid dependency in the UK as “chronically under-researched” despite the UK having the highest levels of opioid use and sales in Europe[3]

.

“There’s a massive amount of anecdotal evidence around this,” says Shapiro, adding that this has resulted in estimates of the number of individuals who might be misusing opioids in the UK varying from tens of thousands to nearly a million.

Shapiro believes that prescription opioid misuse is linked to two main issues. First, the degree to which GPs and pain specialists are trained, and the time they have, to carry out a risk assessment before prescribing opioids in order to gain insight into whether or not an individual is at risk of misusing their prescription. Secondly, the absence of regular monitoring of an individual’s pain during treatment which can lead to patients, such as Kemp, receiving prescription after prescription from their GP.

Courtesy of Harry Shapiro

A report written by Harry Shapiro, director of DrugWise, in 2015 describes the subject of opioid dependency in the UK as “chronically under-researched” despite the UK having the highest levels of opioid use and sales in Europe

A number of factors have been linked to an individual’s risk of misusing prescription opioids, and, as Shapiro says, should be carefully considered by prescribers. Among these are poverty, deprivation, mental ill health and a history of drug misuse.

Roger Knaggs, an advanced pharmacy practitioner specialising in pain management, agrees that more research is required. He says that although opioids are perceived as some of the most effective analgesics available and can be effective for acute pain or for pain at the end of life, there is little evidence that opioids are effective for other types of long-term pain.

“Most studies are of relatively short duration (3–4 months) and are only modestly effective,” he says.

“There is no study of opioid therapy versus placebo, no opioid therapy, or non-opioid therapy evaluated long-term (>1 year) outcomes related to pain, function, or quality of life.

“In addition there is clear evidence of increased harm, particularly at doses above oral morphine equivalent >100mg/day,” he explains.

In Scotland, problem drug use is disproportionately high compared with England and other European countries[4]

. According to statistics from the National Records of Scotland, of the 867 drug-related deaths in 2016, opiates or opioids were implicated in 765 — 159 more than in 2015[5]

. The number of deaths has been attributed to the fact that drug treatment services have been cut leaving some drug users with nowhere to turn for help.

“Problematic use of opiates and benzodiazepine remains a significant issue in Scotland,” says David Liddell, chief executive of the Scottish Drugs Forum.

“The common factor shared across various subgroups within this population is poverty and lack of life opportunities in education and employment.

“Changes within Scottish society and the economy of Scotland that started in the 1970s continue to cause poverty, inequality and disadvantage and these are the key drivers of this and many other issues we face,” he adds.

In June 2017 it was announced that the Scottish Medicines Consortium had recommended buprenorphine oral lyophilisate (Espranor; Martindale Pharma) for restricted use within NHS Scotland as a treatment for opioid drug restriction for patients aged 15 years and over who have agreed to be treated and for whom methadone is not suitable. It is hoped the approval will draw in individuals not currently in supportive treatment.

Taking the right approach

According to Miller there are no fixed clinical standards to guide prescribers around opioids. The Faculty of Pain Medicine, the professional body responsible for the training, assessment, practice and continuing professional development of specialist medical practitioners in the management of pain in the UK, and Public Health England have together produced the Opioids Aware resource. The British Pain Society also have information about the use of opioids but otherwise, guidance is limited in this area and there have been no new evidence-based guidelines from the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) since 2013.

Source: RSZ

Barry Miller, dean of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and a consultant in pain management and anaesthetics, attributes the opioid crisis in the US as being partly due to the influence of pharmaceutical companies

But, he says, with the right approach to opioid prescription and regular pain reviews it would be possible for patients to take opioids for long periods while avoiding the emotional dependence associated with misuse and addiction.

“From our point of view, opioids are overprescribed,” says Heather Wallace, chair of the board of trustees at Pain Concern.

“However, if prescribed correctly — if the patient is assessed and their medication is reviewed regularly — then prescription opioid misuse is uncommon,” she says.

Following an adverse reaction to an antibiotic aged 15, one female patient, who wishes to remain anonymous, began taking opioids for spinal pain. Twenty-five years on, she is still taking eight 20mg oxycodone a day but, combined with pain management techniques learned via a dedicated pain clinic, regular visits to a good physiotherapist and pain psychologist as well as yearly prescription reviews with their GP, she is able to take opioids safely and continue with her life.

“I am physically dependent on the medication to keep my pain under control, but I am not craving it,” she explains.

“I hope I will be able to reduce the opioids for my own health benefits but I am realistic about the pain. The pain clinic has said it may not settle and I may have to stay on my current dose indefinitely.

“I have a four-year-old child and know I want to be healthy and able for him — painkillers give me the ability to take him to the park and work part time.

“Quality of life is important — before, I was screaming every day in bed, now I have a productive life,” she adds.

Pain is one of the most distressing everyday problems we will potentially face in our lives, says Shapiro. A study looking at the prevalence of chronic pain — pain that has existed for more than three months — in the UK found that between a third and half of the UK population, around 28 million adults, are living with chronic pain[6]

. While not all of these people will be taking opioids, there is a need to look at other options by which patients can manage their pain themselves.

Following rehab, Kemp now completely avoids opioids, and instead uses various therapies, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and treatments such as high strength turmeric, as alternative forms of pain management.

Wallace says that ground rules need to be set from the start and doctors need to increase awareness around self-management and the role it can play in helping patients deal with chronic pain.

“Pain treatment is a basic human right but there is no painkiller for chronic pain — 30% pain relief is a good result from an opioid. These medicines work best when you combine them with other ways of managing your pain,” she says.

Miller says the benefit different people get from opioids is very variable.

“Some individuals clearly get a great deal of benefit and others get virtually no benefit but there’s still a reluctance to stop the medication,” he adds.

The crucial role of pharmacists

All healthcare professionals have a contribution to make in tackling this crisis and pharmacists are just as much a part of that. As a pain management specialist, Knaggs spends a large proportion of his time in his clinic discussing the benefits and harms that patients experience from their opioids.

Many patients don’t know how much benefit they gain from opioids or other analgesics, so I encourage gradual dose reduction in order to assess effectiveness and consider de-prescribing

“Many patients don’t know how much benefit they gain from opioids or other analgesics, so I encourage gradual dose reduction in order to assess effectiveness and consider de-prescribing,” he explains.

If there is no marked improvement in pain intensity between four and six weeks of taking the medication, there is unlikely to be any benefit later on and in this case, Knaggs will refer or signpost the patient to other services and also highlight other strategies to manage their pain, such as maintaining physical activity, mindfulness or meditation.

Courtesy, Roger Knaggs

As a pain management specialist pharmacist, Roger Knaggs spends large proportions of his time in his clinic discussing the benefits and harms that patients experience from their opioids

However, pharmacists do not need to be specialists in pain to notice patterns of behaviour in patients and intervene if necessary.

“If you have pharmacists with specialist knowledge of the drugs looking over [a prescription] they can reasonably query whether the mix is appropriate or whether the length of time someone has been on something is appropriate,” says Miller.

“Discussions can then be had to see whether or not that’s right and I suspect in many cases it is not and the medications should be tailed off or stopped.”

Kemp says her pharmacist was a source of great support during the darkest times of her addiction.

“They knew I was going through something I couldn’t control — they were very worried and queried the prescriptions a lot,” she recalls.

The Faculty of Pain Medicine Opioids Aware resource highlights that pharmacists can take a proactive approach to supporting safe opioid prescribing such as ensuring that analgesics available over the counter containing codeine or dihydrocodeine are only used for acute pain of short duration; ensuring that prescribed doses of medication are appropriate for the individual patient; and also supporting monitoring of effectiveness and tolerability of opioids by carrying out medicines use reviews[7]

.

Online pharmacies also need to be considered for the role they can play in facilitating the misuse of opioids

However, online pharmacies also need to be considered for the role they can play in facilitating the misuse of opioids, particularly those that are unregulated.

“Who knows how many people have gone online to buy what,” says Shapiro.

“[There are] online pharmacies that play by the rules and need to see proper prescriptions before they’ll dispense, you’ve got others that have a virtual doctor that asks you a question and if you say yes you get what you want, and others don’t care and will just take your money – and that’s obviously completely unregulated,” he adds.

Rosanna O’Connor, director of drugs, alcohol and tobacco at Public Health England says it is vital that all health professionals make every contact count with patients and are alert to possible signs of misuse and dependence, including to prescribed drugs.

“PHE supports local authorities with advice and data to provide appropriate treatment services, in conjunction with the NHS, to meet a range of dependency problems including addiction to prescribed and over-the-counter medicines,” she says.

Increasing awareness and taking action

Throughout her ordeal, Kemp diarised her experiences with pancreatitis and her consequent opioid misuse. In 2012 she published her experiences in a book and received a huge response from many others who spoke of going through their own experiences with addiction.

But, she says, this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Through her charity, Painkiller Addiction Information Network, her book and appearances at various conferences speaking to GPs, prescribers and commissioners, Kemp has seen an improvement in the level of awareness among healthcare professionals and the public over the past five years, but there are still few places for people to turn.

“The one thing we always come back to is that there are no resources for people — we [now] recognise there’s a problem, but what can we do about the problem and where can we send people? It’s then that we get stumped,” she says.

“When I first started speaking in 2012, people were really shocked and now people are more shocked that there’s no help out there rather than the fact that this condition exists.”

She suggests the need for addiction and pain services to work more closely together — something her charity is campaigning for.

“If we can make that connection — even in primary care, if patients can meet up with a pain team or an addiction team in the area, if we can have days where these services work together I think that would be really beneficial,” she says.

While more research is needed to assess the full scale of the problem of prescription opioid misuse in the UK, it is arguably more important that specialist support and help is made available to patients who see themselves heading towards addiction.

In October 2016, the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence called for a national helpline to support patients affected by Prescribed Drug Dependence[8]

. The helpline service would be targeted at patients who are experiencing side effects of withdrawal as a result of dependence on drugs such as antidepressants, sleeping pills and opioids. It would also provide information for patients who are considering coming off these drugs.

The service will provide a combination of support and guidance including details of local specialist in-person support services, recommendations for non-drug alternatives, and, where appropriate, liaison with the patient’s GP to ensure coordination of treatment.

The helpline proposals have received support from the Royal Colleges and the British Medical Association but discussions are ongoing and are reliant on funding being available.

Although we do not have a full picture of the problem in the UK as yet, we know enough, from stories such as Kemp’s, to realise that there is a vital need for services in this area. Now is the time for government and healthcare bodies to come together to safeguard resources to support those who find themselves in a similar situation and ensure that the problem does not escalate further.

References

[1] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. European Drug Report: Trends and Developments 2015. Available at: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_239505_EN_TDAT15001ENN.pdf (accessed November 2017)

[2] Office for National Statistics. Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2016 registrations — deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales from 1993 onwards, by cause of death, sex, age and substances involved in the death. 2 August 2017. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2016registrations#the-majority-of-drug-misuse-deaths-are-accidental-poisonings (accessed November 2017)

[3] Shapiro H. Opioid painkiller dependent (OPD) An overview. A report written for the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Prescribed Medicine Dependency 2015. Available at: http://www.drugwise.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/opioid_painkiller_dependency_final_report_sept_201.pdf (accessed November 2017)

[4] SPICe The Information Centre; SPICe Briefing: Drug Misuse. 27 March 2017. Available at: http://www.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefingsAndFactsheets/S5/SB_17-22_Drug_Misuse.pdf (accessed November 2017)

[5] National Records of Scotland. Drug-related deaths in Scotland in 2016 – statistics of drug-related deaths in 2016 and earlier years, broken down by age, sex, selected drugs reported, underlying cause of death and NHS Board and Council areas. 15 August 2017. Available at: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files//statistics/drug-related-deaths/drd2016/16-drug-rel-deaths.pdf (accessed November 2017)

[6] Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford et al. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010364. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364

[7] Faculty of Pain Medicine. Role of pharmacists in supporting safe opioid prescribing. Available at: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/faculty-of-pain-medicine/opioids-aware/best-professional-practice/role-of-pharmacists (accessed November 2017)

[8] All Party Parliamentary Group for Prescribed Drug Dependence. Call for national helpline to support patients affected by Prescribed Drug Dependence (PDD) 22 October 2016. Available at: http://prescribeddrug.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Proposal-for-a-national-PDD-helpline.pdf (accessed November 2017)