Mariona Ribó

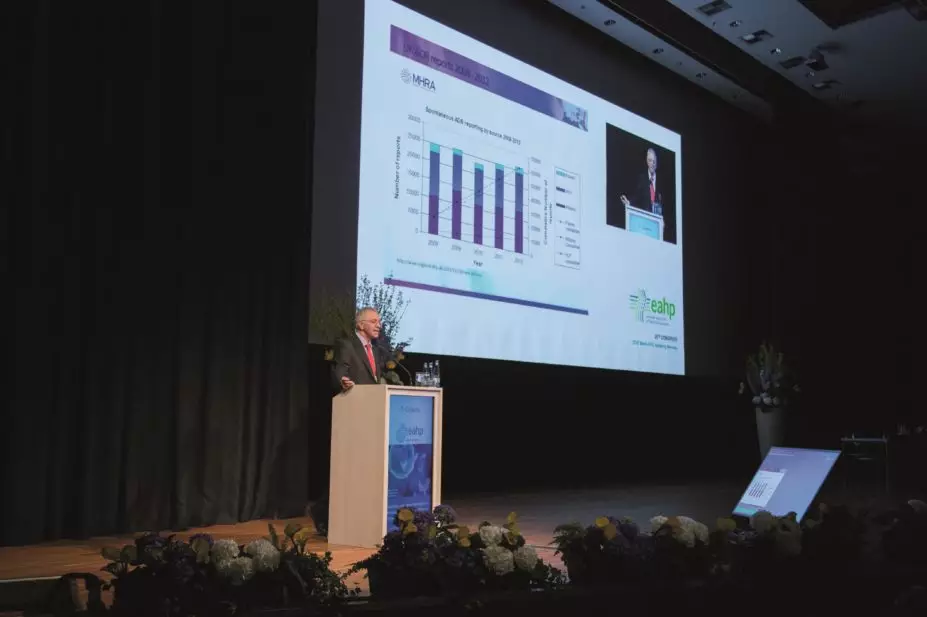

Preventable harm arising from medication-related incidents continues to affect patients in Europe and is a pan-European problem, according to David Cousins, medication and medical devices safety officer at Healthcare at Home Ltd.

Cousins addressed the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists annual congress held in Hamburg, Germany, on 25–27 March 2015 and called for improved European infrastructure to support patient safety.

One example of a preventable adverse drug event in the UK was a case in which a 12-fold overdose of phenytoin was administered to a baby — with fatal results. The staff had misunderstood how to give the loading dose and continued to administer the drug at that level for ten hours. Another case involved a ten-fold overdose of potassium chloride — something that could have been prevented by the use of an administration pump with smart technology, commented Cousins. In a third case, a penicillin allergy was ignored. Although the patient was wearing a red allergy bracelet, neither the doctor nor the nurse involved recognised that Augmentin was a penicillin. The patient developed anaphylactic shock and died.

Cousins drew attention to the Manchester patient safety framework, which describes levels of safety culture starting with ‘pathological’, in which patient safety activity is seen as a waste of time, and working up through ‘reactive’, ‘bureaucratic’ and ‘proactive’ to the ‘generative’ level, in which patient safety is completely integrated into daily practice, information is sought and failures generate more enquiries. It would be valuable for European hospitals to use this simple tool to gauge their culture on an annual basis, he suggested. At present, surveys show there is more interest in gathering financial information about medicines than in reporting safety issues. “Even if managers do not ask for safety data, they should get it alongside the financial data,” said Cousins. Indeed, a World Health Organization resolution in 2002 said that healthcare organisations should “prioritise safety above financial and operational goals”.

From 2005 to 2015, the UK’s National Reporting and Learning System had received 500,000 medication incident reports. The most common causes were omitted medicines and ‘wrong dose’ incidents. Against this background, all large healthcare providers are now required to appoint medication safety officers (MSOs) to support local medication error reporting and learning. So far, 363 organisations have appointed MSOs.

Cousins also highlighted the NHS England “medicines optimisation prototype dashboard”, which contains a useful metric — the total number of incidents with harm reported divided by the total number of incidents reported. A high value is associated with poor reporting culture whereas low values reflect a good reporting culture, explained Cousins, who concluded that hospital pharmacists should play a central role in increasing the governance of medicines and in reporting and learning from incidents.

You may also be interested in

Patient safety commissioner to approach PM over ‘disappointing’ delay to valproate compensation

GPhC writes to pharmacy teams after methotrexate dispensed with instruction to take once daily