“Going gluten-free was a real game changer.” That was the sporty headline carried by the Express online newspaper1 in reference to a story on Novak Djokovic, the Serbian tennis ace who just keeps on winning. Apparently “plagued by tight chest pain and stomach spasms and unable to overcome breathing difficulties and fatigue”, Djokovic was told he had a gluten intolerance, “a diagnosis which would allow the Serbian to overhaul his diet and become the best player in the world”.

On the basis of such headlines it is not hard to see why a diet excluding gluten — a mixture of the proteins gliadin and glutenin — has become so popular in modern times for all manner of reported ills and conditions. The corresponding increase in the availability of gluten-free foods, which now even pervade supermarkets, is estimated to be worth billions annually. What was once a fairly undesirable treatment regimen for a restricted number of people has seemingly turned into a full-blown dietary craze. The popular reading on the topic with titles like “wheat belly” and “grain brain” is further evidence of the changing fortunes of gluten.

Gluten is found in various cereal grains such as wheat, barley and rye and it accounts for a large part of the modern western diet, being present in bread, pasta, cakes and various other foodstuffs. Breakfasts of hot buttered toast and Sunday lunches including Yorkshire puddings reflect the traditional British relationship with gluten.

Some authors have estimated that the frequency of the use of a gluten-free diet outside coeliac disease to be approximately 0.5 per cent

The experiences reported by Djokovic and many others have generated a lot of debate in various medical, scientific and lay circles about whether or not gluten is truly deserving of its growing role as a dietary villain. That is not to say that gluten cannot exert an effect on health as per the example of IgE-mediated wheat allergy or the classic gluten-sensitive enteropathy known as coeliac disease. The confusion seems to arise when wheat allergy or coeliac disease are bundled with reports of gluten intolerance or gluten sensitivity and whether there is such a thing as gluten sensitivity outside those conditions where gluten is known to exert an effect.

Coeliac disease

For the purposes of this article we are going to forgo discussing wheat allergy and instead concentrate on coeliac disease. Coeliac disease is an autoimmune response to gluten, characterised by gastrointestinal symptoms such as functional bowel problems and signs indicative of a state of malabsorption such as anaemia. Science continues to learn about the mechanisms of coeliac disease but the current view is that the condition arises as a function of both genetics and the environment. It all starts with the gluten protein, parts of which are not easily degraded by protease enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract. Segments (peptides) of the gluten protein gain access to the lamina propria (part of the mucosal barrier of our intestinal tract). The enzyme tissue transglutaminase (tTG), which is present at the lamina propria, alters the structure of those gluten peptides in a process called deamidation. This process modifies the peptides in terms of charge and hence binding affinity to the molecules of the major histocompatibility complex also known as the human leukocyte antigen in humans.

A specific type of HLA characterised by the HLA DQ2 or DQ8 heterodimers represents the genetic side of coeliac disease. The interaction between the modified gluten peptides and that specific type of immune system subsequently activates a Th1 CD4+ response after which a host of inflammatory cytokines (chemicals of the immune system) start to work on damaging the gut mucosa.

With these mechanisms in mind, the gold standard diagnostic tests for coeliac disease according to Coeliac UK2 includes serological testing, looking for tissue transglutaminase antibody and endomysial antibody, genetic analysis for the HLA DQ2 and HLA DQ8 genes and a gut biopsy to ascertain the level of any inflammation or damage to the gut mucosa (graded using the Marsh criteria).

The young pretender?

On the basis of various consensus opinions about what is and is not coeliac disease3 and indications that the incidence (not just prevalence) of coeliac disease may truly be on the rise4 among different populations, the question of whether coeliac disease reflects the only way that gluten may affect health and well-being has been increasingly asked.

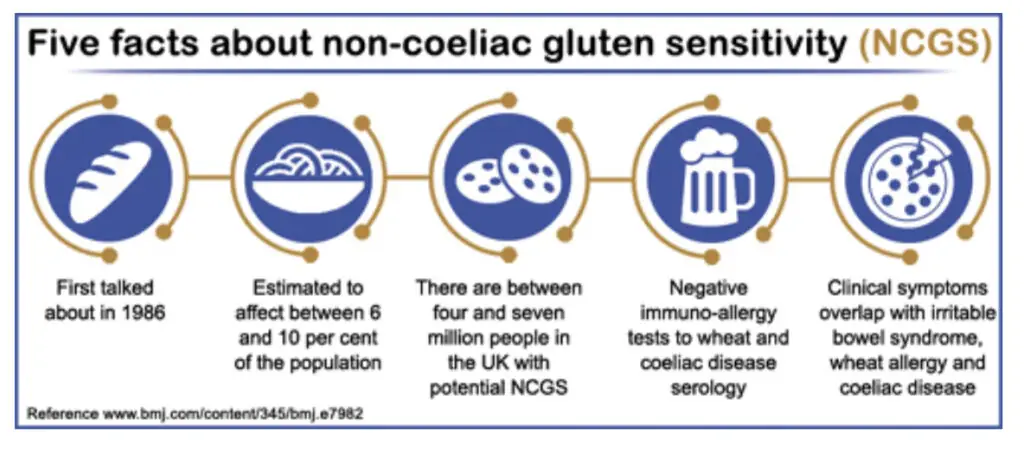

A paper by Catassi and colleagues5 reported on a new frontier of gluten-related disorders beyond coeliac disease. After various expert meetings on gluten sensitivity, Catassi et al highlighted the task ahead in terms of definition and ascertaining prevalence if non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) was indeed going to emerge from the shadows as an equal to its better known gluten-related sibling conditions.

Based on studies of NCGS, including those by Sapone and colleagues on a spectrum of gluten-related disorders6 and the preliminary findings on the differentiation of coeliac disease and gluten sensitivity,7 the weight of evidence for NCGS is slowly moving in favour of an effect albeit with much more to do. Although prevalence data on NCGS is still currently lacking, some authors have estimated that the frequency of the use of a gluten-free diet outside coeliac disease to be approximately 0.5 per cent.8

Experimental studies such as the one reported by Biesiekierski and colleagues9on an effect of NCGS in relation to gastrointestinal symptoms (under double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled rechallenge conditions) contribute to the notion of a non-coeliac effect of gluten in specific patient groups, the focus being on the various bowel complaints that pester a significant portion of the general population and as yet remain unexplained by science. Whether the associated assertions by Carroccio and colleagues10 of differing populations within the spectrum of NCGS holds true has yet to be seen because still more investigation is needed to replicate and verify these findings.

Gluten and psychiatry

As odd as it might sound, one area in particular seems to have received the lion’s share of debate when it comes to NCGS: childhood developmental disorders such as the autism spectrum conditions. There is an interesting but limited body of work linking the presentation of some types of autism to diet and, in particular, foods containing gluten and casein (the protein found in mammalian milk sources).11

The paper by Ludviggson and colleagues12 reported that, although the rates of coeliac disease were not elevated in cases of autism, there was an increased risk of children with autism presenting with the serological markers of coeliac disease without the corresponding bowel findings. This set against previous work indicating similar observations outside coeliac disease in cases of autism13,14 pointing towards the presence of a possible NCGS variant. Such work has generated excitement among some quarters of the autism research community.15

The theory that gluten might be linked to cases of autism is not the only example of a potential NCGS at work in psychiatry. Similar reports have emerged in relation to cases of schizophrenia,16 including the detailing of individual reports of psychiatric symptom abatement following the use of a gluten-free diet.17 In addition there is a history of research suggestive of extra-intestinal effects associated with untreated coeliac disease and other gluten sensitivities.18 Once again, further research is required to substantiate these initial findings and inform whether dietary changes might have any effect.

Conclusions

In these days of celebrity diets and our growing obsession with the health implications of the foods we eat, it is little wonder that reports illustrative of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity continue to emerge in the media and popular press. Although it is easy to pass such reports off as mere speculation and media hype, the suggestion of an effect of gluten outside the classical association with coeliac disease or classical wheat allergy remains a topic of significant speculation with some accumulating evidence of effect for certain groups. At the current time, the precise cause and progression of NCGS is unknown as is the prevalence of such conditions across different populations. The implications of adopting a gluten-free diet both in terms of nutritional value of the gluten-free alternatives and the risk of nutritional deficiency as a result of removing a staple food group have, as yet, received little consideration.

That being said, the growing acceptance of a spectrum of gluten-related issues occurring alongside the more traditional gluten-related conditions may well have far-reaching implications for how we view this staple part of our modern diet and its relationship to our health and well-being.

References

1 Novak Djokovic: going gluten-free was a real game changer. Express. 10 September 2013. Available at: http://www.express.co.uk/life-style/health/428272/Novak-Djokovic-Going-gluten-free-was-a-real-game-changer (accessed 17 December 2013).

2 How to get diagnosed. Coeliac UK. Available at: http://www.coeliac.org.uk/coeliac-disease/how-to-get-diagnosed (accessed 17 December 2013).

3 Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease.Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2012;54:136–60.

4 White LE, Merrick VM, Bannerman E et al. The rising incidence of celiac disease in Scotland. Pediatrics 2013 Sep 9. [Epub ahead of print].

5 Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B et al. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients 2013;5:3839–53.

6 Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Medicine 2012;10:13.

7 Sapone A, Lammers KM, Casolaro V et al. Divergence of gut permeability and mucosal immune gene expression in two gluten-associated conditions: celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. BMC Medicine 2011;9:23.

8 DiGiacomo DV, Tennyson CA, Green PH et al. Prevalence of gluten-free diet adherence among individuals without celiac disease in the USA: results from the Continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 2013;48:921–5.

9 Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2011;106:508–14.

10 Carroccio A, Mansueto P, Iacono G et al. Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2012;107:1898–906.

11 Whiteley P, Shattock P, Knivsberg AM et al. Gluten- and casein-free dietary intervention for autism spectrum conditions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2012;6:344.

12 Ludvigsson JF, Reichenberg A, Hultman CM et al. A nationwide study of the association between celiac disease and the risk of autistic spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2013 Sep 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2048. [Epub ahead of print].

13 de Magistris L, Picardi A, Siniscalco D et al. Antibodies against food antigens in patients with autistic spectrum disorders. BioMed Research International 2013;2013:729349.

14 Lau NM, Green PH, Taylor AK et al. Markers of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity in children with autism. PLoS One 2013;8:e66155.

15 Autism study finds no link to celiac disease; gluten reactivity real. Autism Speaks. Available at: http://www.autismspeaks.org/science/science-news/autism-study-finds-no-link-celiac-disease-gluten-reactivity-real (accessed 15 December 2013).

16 Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P et al. Elevated gliadin antibody levels in individuals with schizophrenia. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2013;14:509–15.

17 Jackson J, Eaton W, Cascella N et al. A gluten-free diet in people with schizophrenia and anti-tissue transglutaminase or anti-gliadin antibodies. Schizophrenia Research 2012;140:262–3.

18 Hadjivassiliou M, Sanders DS, Grünewald RA et al. Gluten sensitivity: from gut to brain. Lancet Neurology 2010;9:318–30.