BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

Key points:

- A broad range of oral over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics are available, at different amounts per tablet, alone or in combination with other ingredients, which makes appropriate medicine selection confusing for patients presenting with symptoms of acute pain.

- Pharmacy is an important point of care for patients experiencing pain and pharmacy professionals have a responsibility to ensure they are able and confident to advise patients in line with the best available evidence.

- Guidelines are available to pharmacy professionals to help them guide patients through the range of treatment options. However, some guidelines have been developed for prescribed doses, rather than OTC doses. Since the evidence base will update more quickly than guidance, it should be consulted in conjunction with guidelines when a patient has a query about acute pain management.

- The patient’s needs will also affect treatment choice. Pharmacy professionals must understand the range of guidance and literature available so they can best advise patients about the most effective treatment for them.

All healthcare professionals interact with people experiencing pain as part of their everyday working lives. Patients often have high expectations of pain management; therefore, providing the best advice on analgesia to patients seeking relief of acute pain in community pharmacy is critical to its function as a point of care.

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”. It says that pain may also occur in the absence of tissue damage or any identifiable pathophysiological cause, and if an experience is subjectively reported in the same way as pain caused by tissue damage, it should be accepted as pain[1]

. However, pain is more than just a symptom of disease; it can be viewed as a disease state in itself.

Pharmacists and pharmacy teams have a duty to provide patients with information and advice that enables them to self-care for acute pain supported by the use of important over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics, while referring patients to other healthcare professionals when appropriate. This article explores what acute pain is, as well as the importance of reviewing guidelines and the evidence base regularly, to support making appropriate oral OTC analgesic recommendations to adult patients.

Consider guidelines alongside evidence

There are no specific guidelines about how to manage acute pain with OTC medicines at low dose and for short durations. However, there are several national and international guidelines, as well as indication-specific guidelines, available for the prescription of oral analgesics for pain management (see Useful resources).

It is important to consider that although some patients may respond well to a given analgesic, others may respond poorly. Therefore, pharmacists and pharmacy teams should initiate conversations with patients about what they have taken previously (if anything) and how they have taken it.

As well as consulting the guidelines, pharmacists and pharmacy teams should also consider the ever-changing evidence base (see our learning article ‘How to understand and interpret clinical data’ for more information). This is especially important when several years have passed since the relevant guidelines were updated and/or when there is a difference between prescribed and OTC analgesics.

Understanding pain

Pain is a conscious, subjective experience that is shaped by both the stimulus and the psychological response to the experience. Although pain is commonly thought of as a sensation in a part or parts of the body, it is always unpleasant and, therefore, is also an emotional experience. Treating patients who have severe or complex pain problems is challenging. Therefore, pain specialists aim to avoid:

- Acute pain becoming chronic (i.e. a long-term experience);

- The memory of pain causing potentially harmful situations in the future.

Acute pain versus chronic pain

Clinically, pain is often divided into two categories: acute and chronic. Acute pain lasts for less than three months and serves as a warning to alert the body to a problem, with the aim of preventing further tissue injury[2]

. It is often proportional to the severity of injury and usually resolves itself when tissue healing is complete. At any given point in time, the proportion of adults with pain in the UK has been estimated to be around 5%[3]

. The majority of acute pain episodes arise from causes that can be categorised as musculoskeletal conditions[2]

. For example, pain associated with a broken ankle tells the individual that something is wrong and that they should protect the injured area by immobilising it. Chronic pain, on the other hand, persists beyond the expected time of healing or beyond three months[2]

.

Aims of pain management

It is important to reach a shared decision with the patient about pain relief, including their pain management goals and requirements, which can include[4]

:

- Reducing the intensity of pain;

- Enhancing physical functioning;

- Improving psychological functioning;

- Reducing use of healthcare services;

- Promoting return to work or school and/or role within family and society;

- Improving health-related quality of life;

- Supporting pain-management planning decisions.

The patient’s needs will also affect treatment choice. Therefore, pharmacists and pharmacy teams must understand the range of guidance and literature available so they can best advise patients about the most effective treatment for them.

Guidelines on managing acute pain

NHS England has produced guidance about a range of conditions that can be treated with OTC medicines[5]

. Patients are encouraged to self-care for the following acute pain conditions: aches and pains, bruising, colds, cuts, earache, fever, headache, period pain, recovery after a simple medical procedure, self-limiting musculoskeletal pain, sinusitis/nasal congestion, sore throat, sprains and strains, teething and toothache[5]

. However, self-care generally means that patients are presented with a broad range of oral OTC analgesics at different concentrations per tablet, alone or in combination with other ingredients, which makes appropriate medicine selection confusing.

Pharmacists and pharmacy professionals should use guidelines supported by a review of the latest evidence as a basis for recommending OTC oral analgesics for acute pain, while bearing the aforementioned caveats in mind.

Recommendations and guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has produced a clinical knowledge summary (CKS) for mild-to-moderate pain[6]

, which aims to provide primary care practitioners with a readily accessible summary of the current evidence base and practical guidance on best practice[6]

. It recommends that the underlying cause of the pain should be treated whenever possible and that a full therapeutic dose is used before switching to a different analgesic[6]

. The CKS was most recently updated in September 2015 and is due for review by December 2020[6]

. Although the CKS provides a good overarching summary of the evidence base and guidance, first-line recommendations in it differ from some of the indication-specific recommendations (see Table). Consequently, it is worth checking both the CKS and indication-specific recommendations when supporting patients in self-care for acute pain, before supplementing this review by examining the evidence-base (see ‘Why the evidence base should be consulted alongside guidance’).

The table shows some commonly presenting conditions and the recommended OTC evidence-based analgesia.

| Table: Common acute pain conditions and the recommended, over-the-counter, evidence-based analgesia | |

| Presenting condition | Evidence-based recommended analgesic |

| Lower back pain | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g. ibuprofen 400mg three times per day) at the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible time. Do not offer paracetamol alone. |

| Tension-type headache | Aspirin (300mg three times per day), paracetamol or NSAID, taking into account patient preference and comorbidities. |

| Migraine (must be medically diagnosed before over-the-counter medication can be recommended) | Combination of triptan (e.g. sumatriptan no more than two 50mg tablets in 24 hours), NSAID or triptan, and paracetamol. If the patient prefers one drug only, consider monotherapy with oral triptan, or NSAID (e.g. ibuprofen) or paracetamol alone, taking into account comorbidities. Opioids should not be used for the acute treatment of migraine. |

| Sprains and strains | Paracetamol (500mg to 1g four times per day, with a maximum 4g in 24 hours) or topical NSAID (e.g. ibuprofen or diclofenac gels) are recommended first-line. Consider oral NSAID (e.g. ibuprofen 400mg three times per day) 48 hours after the initial injury if needed. |

| Period pain | NSAID (e.g. ibuprofen or naproxen) unless contraindicated. Paracetamol can be used if a NSAID is contraindicated or provides insufficient pain relief. |

Sources: National Institute of Health and Care Excellence[8]

| |

[23]

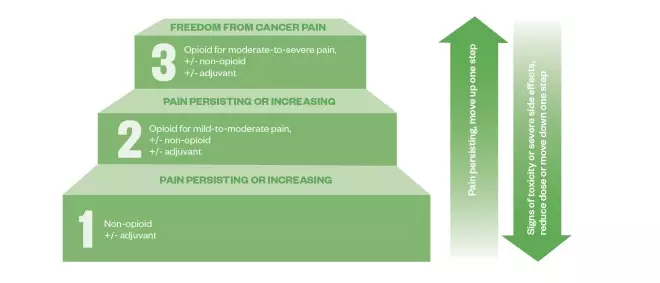

Even though the first-line recommendations vary, all guidelines are in agreement of a step-wise approach to pain management. Figure 1 provides an example from the World Health Organization’s step-wise approach to pain management.

OTC analgesia options

The NICE CKS recommendations state that combination analgesics should be avoided as first-line treatment because prescribing single constituent analgesics allows independent titration of each medicine[6]

. The first-line treatment recommendations vary and additional factors, including clinical presentation, patient comorbidities and contraindications, need to be taken into account[6]

and the evidence base used to determine whether use of any analgesic at an OTC dose over a short duration would be both safe and effective for the patient.

Pharmacists should always check the summary of product characteristics and advise the patient to read the patient information leaflet, paying particular attention to the directions on how to take the analgesic. Each analgesic is discussed in this context below and includes essential information about cautions, risks and contraindications.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Ibuprofen is the first-line recommendation for a range of aches and pains, including lower back pain[7]

, period pain[8]

and toothache.

Aspirin is also used for aches and pains, such as headache, migraine, toothache and period pain. It can be used to treat colds and ‘flu-like’ symptoms, and to bring down a fever (38°C and above). Although aspirin can be used first line for migraine[6],[9]

, other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g. ibuprofen) tend to be preferred as they are better tolerated.

Other considerations

NSAIDs should not be sold to patients with active gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding or active GI ulcer; history of GI bleeding related to previous NSAID therapy or history of recurrent GI ulceration (two or more distinct episodes); a history of hypersensitivity/severe allergic reaction to an NSAID — for example, asthma, rhinitis, angioedema or urticaria; severe heart failure; severe liver impairment; or severe kidney impairment[6],[10],[11]

.

Aspirin is contraindicated in history of hypersensitivity to aspirin or any other NSAID, which includes those in whom attacks of asthma, angioedema, urticaria, or rhinitis have been precipitated by aspirin or any other NSAID[12]

. More frequent review and monitoring of adverse effects is required for patients who are recommended NSAIDs, especially older people; people with comorbidities; people who take medicines that may interact with a NSAID; and those at increased risk of GI or cardiovascular adverse effects[13]

.

Paracetamol

This is a suitable first-line choice for most adults with mild-to-moderate pain[6]

, based on the expert opinion of the Committee on the Safety of Medicines Pain Management Working Group, which comprises members from the British Pain Society and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and was published in 2004[14]

.

Paracetamol is specifically recommended first-line for management of strains and sprains[15]

.

Other considerations

Paracetamol has no known GI, renal or cardiac adverse effects at usual OTC and prescribed doses (1–2 tablets four times daily as required)[6]

. However, pharmacists and pharmacy professionals should check with the patient when paracetamol was most recently administered and the cumulative paracetamol dose over the previous 24 hours to prevent overdose[16]

.

Codeine

Often combined with paracetamol in OTC preparations (co-codamol), codeine can be offered for a variety of acute aches and pains, although it is rarely a first-line treatment recommendation. It should only be offered for managing acute lower back pain if an NSAID is contraindicated, not tolerated or has been ineffective[7]

. Opioids should not be recommended for the acute treatment of tension-type headaches or migraines[17]

.

Other considerations

Caution should be used with the long-term use of weak opioids because tolerance and dependence can occur[6]

. Co-codamol is contraindicated in acute ulcerative colitis; antibiotic-associated colitis; conditions where abdominal distention develops; conditions where inhibition of peristalsis should be avoided; and known ultra-rapid codeine metabolisers[18]

.

Figure 1: The three-step World Health Organization analgesic ladder

Source: World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder was introduced in 1986 as a tool for the treatment of pain caused by cancer. Although developed for chronic pain, the principle of using a step-wise approach to analgesia, using stronger analgesia for more severe pain and a step-down approach in cases of toxicity or side effects would be relevant principles to apply to the management of acute pain.

Over-the-counter analgesics can be used for mild pain according to this tool, starting with a non-opioid (e.g. paracetamol or aspirin) for mild pain and moving to opioid plus a non-opioid (e.g. co-codamol) for mild-to-moderate pain. Despite its origin in the management of cancer-related pain, the WHO analgesic ladder now provides a useful guideline for pain management of both acute and chronic pain from malignant and non-malignant causes. However, as pain is a subjective experience, the step-wise escalation on the WHO analgesic ladder may not always be appropriate for managing intense pain[19]

Why the evidence base should be consulted alongside guidance

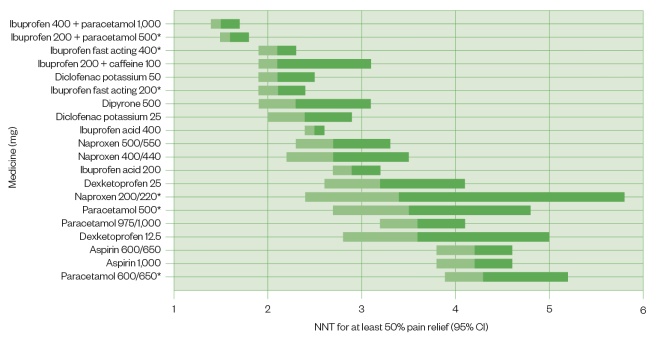

An overview of 39 Cochrane reviews of randomised controlled trials on the efficacy of OTC analgesics in acute pain found that there is a reliable body of evidence to show that simple, inexpensive, readily available analgesics give good pain relief to many patients with acute pain, such as toothache, sprains and strains. The data showed that the most efficacious OTC drugs used were ibuprofen/paracetamol combinations in respective 400mg/1,000mg and 200mg/500mg doses[20]

.

These formulations gave effective relief in seven out of ten patients, with a number needed to treat (NNT; see learning article ‘How to understand and interpret clinical data’) of less than two. Fast-acting ibuprofen 200mg and 400mg was effective in at least five out of ten patients, with a NNT of between two and three patients. Paracetamol alone helped four out of ten patients, with a NNT of between three and five patients, depending on dosage (see Figure 2)[20]

.

Figure 2: A bar graph showing the number needed to treat for analgesics

Source: Reproduced with permission from Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews[20]

Number needed to treat (NNT) for over-the-counter medicines where a minimum of two studies with 200 participants were available (NNT for at least 50% maximum pain relief over four to six hours compared with placebo).

The bars show the 95% confidence interval

*Available in the UK

(CI) and the colour change represents the point estimate.

The overview highlighted an absence of evidence on the efficacy of low-dose codeine, which is found in several OTC preparations[20]

.

This overview of the evidence base demonstrates that simple drug combinations and fast-acting formulations deliver good analgesia in many people with acute pain, at relatively low doses. For example, if paracetamol is started at low dose, it can be increased to a maximum of 1,000mg four times per day before switching to or combining with another analgesic. Ibuprofen 400mg three times per day is a low dose that can be increased to 2,400mg daily, if a higher dose is required and not contraindicated[6]

.

The authors of the overview also question the standard advice supplied with ibuprofen, naproxen, aspirin and other NSAIDs to take them with food. They called for future research in this area as it may be possible that absorption of the drugs is hastened by having an empty stomach[20],[21]

. Since publication of the overview, and following submission and review of clinical evidence by the MHRA, some patient information leaflets for ibuprofen have been updated to state that it needs to be taken with water, with no reference to taking it with food[22]

. Pharmacists should always check the summary of product characteristics to check for updates and to advise patients on correct administration.

Summary

Pharmacists and pharmacy teams have a wide range of guidelines to help patients decipher this range of treatment options. However, it is important to bear in mind that the evidence base updates more quickly than guidance. Therefore, for patients who are not happy with their current pain relief and want to self-care for acute pain resulting from the common conditions described previously, it is worth re-evaluating guidance and the literature in order to provide the most up-to-date evidence-based advice. This will help them select the most appropriate treatment from the range of medicines available.

What now?

Further information and support on how to read the evidence base (‘How to understand and interpret clinical data’) has been produced as part of this campaign and should be used to supplement this article in practice.

The final article in this campaign will examine how behaviour changes can be implemented in through effective patient consultations for acute pain by providing practical tips about how to put guidelines and the evidence base into practice when interacting with patients who have acute pain in a community pharmacy setting.

Useful resources

- General pain guidelines

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical knowledge summary: analgesia — mild-to-moderate pain. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/analgesia-mild-to-moderate-pain#!scenarioRecommendation:1

- Indication-specific guidelines

- Headache

- NICE. Headaches in over-12s: diagnosis and management [CG150]. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg150;

- British Association for the study of Headache. Guidelines for all healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache and medication-overuse headache. 2010. Available at: http://www.bash.org.uk/guidelines/;

- International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 3rd edn. 2018. Available at: http://www.ihs-headache.org/ichd-guidelines;

- NICE. Low back pain and sciatica in over-16s: assessment and management [NG59]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/chapter/Recommendations

- Dysmenorrhoea

- NICE. Clinical knowledge summary: dysmenorrhoea. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/dysmenorrhoea#!scenario

- Sprains and strains

- NICE. Clinical knowledge summary: sprains and strains. 2016. Available at:

https://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!scenario

- NICE. Clinical knowledge summary: sprains and strains. 2016. Available at:

Lower back pain and sciatica

- Headache

Safety, mechanism of action and efficacy of over-the-counter pain relief

These video summaries aim to help pharmacists and pharmacy teams make evidence-based product recommendations when consulting with patients about OTC pain relief:

- Safety of over-the-counter pain relief

- Mechanism of action of over-the-counter pain relief

- Efficacy of over-the-counter pain relief

Promotional content from Reckitt

References

[1] International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Classification of Chronic Pain. IASP terminology. 2017. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698&navItemNumber=576 (accessed July 2019)

[2] Royal College of Anaesthetists Faculty of Pain Medicine. Introducing pain management. Epidemiology and the burden of pain. 2013. Available at: https://portal.e-lfh.org.uk/Component/Details/82159 (accessed July 2019)

[3] Department of Health. Pain: breaking through the barrier. 2008. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130105045453/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_096233.pdf (accessed July 2019)

[4] International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP interprofessional pain curriculum outline. 2018. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/CurriculumDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=2057 (accessed July 2019)

[5] NHS England. Conditions for which over-the-counter items should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: Guidance for CCGs. 2018. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/otc-guidance-for-ccgs.pdf (accessed July 2019)

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: analgesia — mild-to-moderate pain. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/analgesia-mild-to-moderate-pain#!scenarioRecommendation:1 (accessed July 2019)

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE guidance [NG59]. lower back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/chapter/Recommendations (accessed July 2019)

[8] National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: dysmenorrhea – primary dysmenorrhea. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/dysmenorrhoea#!scenario (accessed July 2019)

[9] British Association for the Study of Headache. Guidelines for all healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, medication-overuse headache. 2010. Available at: http://www.bash.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/10102-BASH-Guidelines-update-2_v5-1-indd.pdf (accessed July 2019)

[10] British National Formulary. Ibuprofen. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/ibuprofen.html (accessed July 2019)

[11] British National Formulary. Naproxen. 2015. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/naproxen.html (accessed July 2019)

[12] British National Formulary. Aspirin. 2017. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/aspirin.html (accessed July 2019)

[13] National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: NSAIDs – prescribing issues. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/nsaids-prescribing-issues#!scenarioRecommendation:5 (accessed July 2019)

[14] Committee on the Safety of Medicines Pain Management Working Group. Advice on analgesic options in treatment of mild to moderate pain in adults. 2004. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20080611060618/http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-a/documents/websiteresources/con019464.pdf (accessed July 2019)

[15] National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summary. CKS Sprains and Strains. 2016. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/sprains-and-strains#!scenario (accessed July 2019)

[16] British National Formulary. Paracetamol. 2017. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/paracetamol.html (accessed July 2019)

[17] National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Headaches in over-12s: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG150]. 2012. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg150/chapter/Recommendations#management-2 (accessed July 2019)

[18] British National Formulary. Co-codamol. 2017. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/co-codamol.html (accessed July 2019)

[19] World Health Organization. WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. 2002. Available at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/ (accessed July 2019)

[20] Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S et al. Non-prescription (OTC) oral analgesics for acute pain - an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;4(11):CD010794. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010794.pub2

[21] Cochrane UK. How well do over-the-counter painkillers work? 2015. Available at: https://uk.cochrane.org/news/how-well-do-over-counter-painkillers-work (accessed July 2019)

[22] Emc. Boots ibuprofen caplets 200mg (GSL). 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9029/pil (accessed July 2019)

[23] National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summary. CKS Back pain — low (without radiculopathy). 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/back-pain-low-without-radiculopathy#!scenario (accessed July 2019)