Steve Gschmeissner / Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- How helminths are classified

- How to diagnose and treat helminth infections common in the Western world

- How helminth infections common in the third world are diagnosed and treated

Helminths either live as parasites, or free of a host, in aquatic and terrestrial environments. There are several types; the most common worldwide are intestinal nematodes or soil-transmitted helminths (STH), schistosomes (parasites of schistosomiasis) and filarial worms, which cause lymphatic filariasis (LF) and onchocerciasis.

An estimated 819 million people worldwide are infected with Ascaris (common roundworm), 464 million with Trichuris (whipworm), and 438 million with hookworm[1]

. Infection is generally most prevalent among rural communities in warm, humid equatorial regions and where sanitation facilities are inadequate. Of the 5.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) caused by STHs globally, 62% are attributable to hookworm[1]

.

Schistosomiasis is endemic in 70 countries with over 200 million people infected; most living in poor communities without safe drinking water or adequate sanitation. An estimated 90% of those infected live in sub-Saharan Africa, where up to 20 million people suffer severe chronic health consequences. Schistosomiasis is estimated to cause 3.3 million DALYs[1]

.

LF is endemic in 83 countries with an estimated 120 million cases, including 25 million with hydrocele and 15 million with lymphoedema. LF is estimated to cause 2.8 million DALYs[1]

.

Helminth infestation causes morbidity and mortality: it compromises nutritional status, affects cognitive processes, induces tissue reactions and causes intestinal obstruction or rectal prolapse. For reasons not well understood, school-aged children (including adolescents) and pre-school children tend to harbour the greatest numbers of intestinal worms and schistosomes and, as a result, experience stunted growth and diminished physical fitness, as well as impaired memory and cognition that leads to educational deficits[2]

. Helminthiasis control requires combined drug treatment, improved sanitation and health education.

Classification

Helminths are invertebrates characterised by elongated, flat or round bodies. Flatworms (platyhelminths) include flukes (trematodes), tapeworms (cestodes) and roundworms (nematodes). Further subdivision is designated by the residing host organ (e.g. lung flukes and intestinal roundworms).

Flukes, or trematodes, are leaf-shaped, and vary in length from a few millimetres to 8cm. Excluding blood flukes, trematodes are hermaphroditic, having both male and female reproductive organs. Both self-fertilisation and cross-fertilisation occur. Blood flukes (schistosomes) are the only bisexual flukes that infect humans (see ‘Common flukes [trematodes]’). Within the definitive (human) host, male and female worms inhabit the lumen of blood vessels and are found in close physical association. Flukes go through several larval stages before reaching adulthood. Eggs are passed in the faeces, urine, or sputum of humans and, on reaching an aquatic environment, the eggs hatch, releasing ciliated larvae, which either penetrate or are eaten by snail intermediate hosts. A sporocyst develops from a miracidium within the tissues of the snail, producing cercariae that migrate to the external, usually aquatic, environment. Cercariae penetrate the definitive host and transform directly into adults.

| Common flukes (trematodes) | |

|---|---|

| Organ inhabited | Fluke |

| Lung | Paragonimus westermani |

| Intestine | Fasciolopsis buski, Heterophyes heterophyes, Mettgonimus yokagawi |

| Liver | Clonorchis sinensis, Opithorchis species, Fasciola hepatica |

| Blood | Schistosoma mansoni, Shistosoma haematobium, Schistosoma japonicum |

Tapeworms, or cestodes, are flat, hermaphroditic, parasitic worms that colonise the human gastrointestinal tract. Some are primarily human pathogens, others are animal pathogens that also infect humans. Adult tapeworms are elongated, segmented, flatworms that inhabit the intestinal lumen. Larval forms, which are cystic or solid, inhabit extra-intestinal tissues and include Taenia saginata, Taenia solium, Diphyllobothrium latum, Hymenolepis nana andEchinococcus species.

Segments (proglottids) are hermaphroditic and vary in length from 2mm–10m, with three to several thousand segments per adult tapeworm. Eggs are released when tapeworms shed gravid proglottids into the intestine, which are then shed in stools. All eggs are embryos that develop into different larval stages in both the immediate host (crustacean) and intermediate host (vertebrate). Larvae develop into adults in the definitive (human) host[3]

.

Roundworms, or nematodes, are cylindrical in structure and usually bisexual; copulation between the male and female is important in fertilisation. Most nematodes that are parasitic in humans lay eggs that, when voided, contain either a zygote or a completely formed larva. Some nematodes, such as the filariae and Trichinella spiralis, produce larvae that are deposited in host tissues. The developmental process involves egg, larval and adult stages[3]

. Classification is via infection mode: direct, modified direct, or skin penetration. Direct infection occurs when eggs are transmitted from anus to mouth without reaching soil (e.g. Enterobius vermicularis [pinworm/threadworm] and Trichuris trichuria [whipworm]). Modified direct infection occurs when eggs passed in faeces only become infectious following incubation time in soil (e.g. Ascaris lumbricoides [roundworms]). Skin penetration is used by hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenale andNecator americanus)[4]

.

Diagnosis and treatment of helminth infections

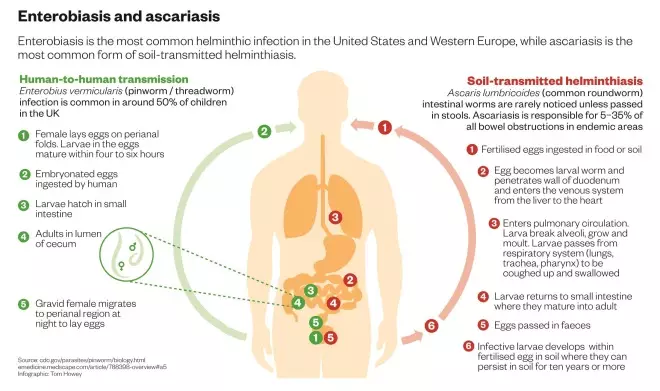

Enterobiasis is the most common helminthic infection in Western Europe and is caused by Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm/threadworm). Gravid adult worms deposit eggs in perianal folds (see ‘Enterobiasis and ascariasis’). Auto-infection can occur by scratching the perianal area and transferring infective eggs to the mouth with contaminated hands. Person-to-person transmission occurs by contaminating surfaces or food items with infective eggs.

Most infections are asymptomatic but pruritus ani is common. Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting are experienced in patients with high worm burden.

Investigation to confirm enterobiasis involves the pinworm paddle or tape test, where tape is applied to the perianal areas (sticky part of the tape down) mainly at night. The tape can then be examined microscopically.

Treatment of enterobiasis is focused on the whole family on the first occasion of infection only[5]

. Mebendazole (100mg immediate dose) is the treatment of choice for enterobiasis infection. If re-infection occurs, the dose can be repeated in affected individuals after two weeks (children older than six months and adults)[6]

. Mebendazole is contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Re-infection of threadworm from fingers and contaminated objects is easy and patients should be advised to avoid scratching and ensure to scrub under nails. Bedding and clothing should be boil-washed or ironed with a hot iron to kill the eggs.

Ascaris (common roundworm) intestinal worms are rarely noticed unless passed in stools. Worms may form a bolus in heavy infections causing intestinal obstruction, volvulus or perforation. In endemic areas, 5–35% of all bowel obstructions are caused by ascariasis[7]

. Wandering worms can obstruct ducts or diverticular causing biliary coli, cholangitis, liver abscess, pancreatitis or appendicitis, or can occasionally be coughed up in sputum (see ‘Enterobiasis and ascariasis’).

The most common clinical presentation is Ascaris pneumonitis. Fever, cough, dyspnoea and urticaria may occur in a proportion of those infected on account of migration of larvae through the lungs. A. pneumonitis infection accompanied by eosinophilia is known as Loeffler’s syndrome. Symptoms usually resolve spontaneously after ten days as a result of migration of the worm through the lungs.

A number of investigations can confirm clinical diagnosis of A. pneumonitis. Larvae and eosinophils may be found in sputum. A chest X-ray can confirm the presence of larvae and stool microscopy is adequate in established infections (may be negative if all worms are male).

Treatment of adults aged over 18 years after positive diagnosis of A. pneumonitis is usually with albendazole 400mg immediate dose or mebendazole 500mg immediate dose[5]

. In children aged 1–2 years, mebendazole 100mg twice daily should be given for three days. In children aged 2–18 years, mebendazole should be given 100mg twice daily for three days, or mebendazole 500mg immediate dose[6]

.

Toxocara canis and T. catis

are parasitic roundworms of dogs and cats that are prevalent worldwide. Human infection occurs after ingestion of eggs in sand or soil contaminated by dog or cat faeces. The United States has a seroprevalence of 13.9%[8]

, however it is more prevalent in the developing world. Toxocara eggs are not infective until two weeks post-shedding and ingestion of fresh dog or cat faeces is not a route of transmission. If old faeces are ingested, serological testing (ELISA) could be performed immediately and repeated three months later.

In infections with T. canis and T. catis, patients may present with visceral larva migrans (VLM) caused by migrating larvae that produce symptoms and signs including pneumonitis, fever, abdominal pain, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, sleep and behaviour disturbances, and focal and generalised convulsions. Ocular larva migrans (OLM) may occur in lighter infections caused by larvae migrating to the eye producing a granulomatous reaction in the retina. This may present as visual disturbance or blindness, which is diagnosed via ophthalmoscopy.

Patients with suspected T. canis and T. catis infection should have a full blood count taken and can undergo serology (ELISA). Eosinophilia and anaemia are indicative of active infection. Positive serology tests using ELISA suggest the production of antibodies against antigens produced by the presence of worms and this is confirmed by Western blot.

For the treatment for VLM and confirmed non-ocular cases, patients aged over 18 years should be given albendazole (unlicensed) 400mg twice daily for seven days[5]

. Suspected ocular involvement requires urgent referral for an ophthalmologist’s opinion.

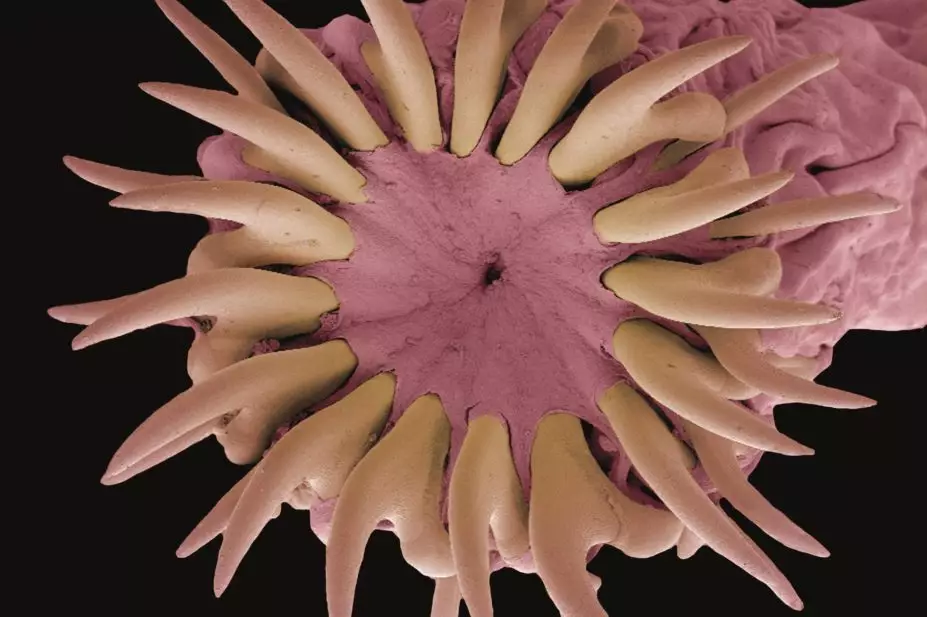

Photo guide: Helminth parasites

Source: Science Photo Library, Wikimedia Commons

1) Schistosome parasite

2) Scolex (head) of the adult beef tapeworm Taenia saginata

3) Echinococcus granulosus scolex

Taenia saginata, or beef tapeworm, causes taeniasis (see ’Photo guide: Helminth parasites’). Patients with T. saginata infection are usually asymptomatic and often only present after having passed a proglottid segment in stools. Patients can present with gastrointestinal symptoms (loss of appetite, nausea or abdominal pain). Rare complications of T. saginata infection occur when segments of proglottids migrate to the appendix, bile or pancreatic duct, causing vomiting. Several metres of tapeworm may also be passed in vomit[9]

.

Investigation for T. saginata involves stool microscopy. Laboratory confirmation of species should occur before treatment, where stool samples are available.

Adults aged over 18 years should be given niclosamide 2g immediate dose or praziquantel (unlicensed indication) 10mg/kg immediate dose; except in cases of Hymenolepis

nana, where praziquantel (unlicensed indication) 30mg/kg should be given immediately. In children aged over four years, praziquantel 5–10mg/kg should be given immediately or 25mg/kg for H.

nana

[6]

.

Taenia solium

, or pork tapeworm, causes cysticercosis. Infected patients will usually present with muscle pain and swelling during initial invasion and development of cysts. Skin nodules may also be present. Calcified cysts in skeletal muscle fibres can be seen on X-rays. In patients experiencing symptoms of new or recent onset epilepsy, this could be indicative of cysts in the brain.

Investigation to confirm T. solium infection involves a full blood count, eosinophilia is usually present, stool microscopy and serology. Patients experiencing neurological symptoms should undergo brain imaging (computerised tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]).

Treatment of cerebral T. solium infection should focus on prioritising symptom control with adequate anticonvulsant therapy. Antiepileptic medication, such as phenytoin, carbamezapine, levetiracetum or tompiramite, could be used[10]

. In cerebral infection, antihelminthic treatment is not considered urgent and may not always be necessary or appropriate[5]

. No treatment is recommended for calcified cysts; endoscopic removal can be performed on ventricular cysts, however, this is only recommended in moderate infections with viable cysts. Antihelminthic use should always be under steroid cover that is carefully considered and discussed with a specialist consultant.

Although both are unlicensed, in adults aged over 18 years albendazole 15mg/kg can be given once daily for eight days in patients who are not pregnant or breastfeeding, or praziquantel 50mg/kg can be given once daily in divided doses for 15 days. Steroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) should also be given and doses and regimen must be discussed with a specialist consultant[5]

.

Fasciola hepatica

infections occur in sheep-rearing areas of temperate climate such as in England and Wales[11]

.

Most infections with F. hepatica are mild and morbidity increases with fluke burden. The acute phase occurs 6–12 weeks post-infection and patients often present with fever, right upper quadrant pain, hepatomegaly and occasionally jaundice. In heavy infections, extensive liver parenchyma necrosis can occur and extra hepatic symptoms (e.g. Loeffler’s syndrome), could occur. The chronic phase usually occurs six months post-infection and can last for ten years or more. Patients are usually asymptomatic, although epigastric and right upper quadrant pain, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, wasting and hepatomegaly can occur. Jaundice is a common complication caused by bile duct obstruction. The most common ectopic site of extra hepatic fascioliasis is in the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior abdominal wall, although all other viscera may be affected.

Investigational tools for diagnosis include microscopy of stools, or duodenal or bile aspirates. Endoscopy can be performed, and often adult worms may be found blocking the biliary tract. Positive serology tests using ELISA suggest the production of antibodies against antigens produced by the presence of worms (alive or dead). Infection is confirmed by microscopic examination of eggs in stools.

Although unlicensed and contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding, triclabendazole 10mg/kg once daily for two days is the treatment of choice in adult patients aged over 18 years[5]

.

Schistosomiasis (‘bilharziasis’) is an infection with parasitic blood flukes: Schistosoma mansoni, S. haematobium, S. japonicum, S. interculatum andS. mekongi (see ’Photo guide: Helminth parasites’). NHS data from England reported 77 cases in 2011–2012 and all cases developed in people who had travelled abroad[12]

. Regions where cases are most prevalent are freshwater areas in sub-Saharan Africa (such as Lake Malawi), South East Asia (Mekong River in Cambodia and Laos), and Japan[12],[13]

.

Most infected patients are asymptomatic because of low worm burden[14]

. Acute infection can manifest in a number of ways. Swimmer’s itch is an itchy rash that may appear after swimming in fresh water (see ’Photo guide: Helminth pathologies’). Katayama fever or acute schistosomiasis syndrome occurs three to eight weeks after infection. Patients often experience sudden onset of fever, urticaria and angioedema, chills, myalgias, arthralgias, dry cough, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and headache. This coincides with egg production and increased antigen burden. Symptoms are usually mild and resolve spontaneously in a few days to weeks.

In chronic infection, symptoms usually develop months or years after infection. Symptoms of intestinal schistosomiasis include poor appetite, intermittent abdominal pain and diarrhoea. Patients with heavy worm burden often have colonic ulceration and iron deficiency anaemia. In hepatosplenomegaly schistosomiasis, periportal fibrosis causes an enlarged liver and spleen, leading to occlusion of the portal veins, portal hypertension with splenomegaly, portocaval shunting and gastrointestinal varices.

Investigation to confirm diagnosis includes microscopy to identify Schistosoma eggs in stools and urine, and serology testing using ELISA.

Patients with confirmed schistosomiasis, should be referred to a specialist centre. Praziquantel is only effective against adult schistosomes, which are fully mature at three months. Screening should be delayed until this point and serology may remain positive for years despite treatment. Praziquantel (unlicensed indication) 20mg/kg dose should be given immediately and repeated once four to six hours later (children aged over four years and adults)[6]

. Nausea and vomiting are likely side effects of praziquantel treatment and patients should be advised to take their tablets in the evening.

Katayama fever should be treated as above, plus steroids (e.g. prednisolone 20mg daily) and repeat praziquantel doses six weeks later.

Ancylostoma duodenale

andNicator americanus, or hookworm infections are not endemic in the UK, but infections are sometimes observed in travellers returning from the tropics. Most patients are asymptomatic, but will often experience abdominal discomfort, flatulence, anorexia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea (sometimes containing blood and mucous). Iron deficiency anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and cardiac failure secondary to anaemia may also occur. ‘Ground itch’ may occur at the site of penetration and serpiginous rash of cutaneous larva migrans may be seen in hookworm infections (see ’Photo guide: Helmith pathologies’). This is more commonly associated with infection of dog/cat hookworm.

A full blood count should be taken to confirm diagnosis, with eosinophilia common during tissue migration. Faecal microscopy and stool cultures are also performed to determine whether eggs are present.

The main treatments for hookworm are albendazole 400mg immediate dose (in those aged over two years)[6]

or mebendazole 100mg twice daily for three days (in those aged over one year)[6]

. Both are contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Cutaneous larva migrans can be treated in adults aged over 18 years with ivermectin (unlicensed indication) 200µg/kg immediate dose or albendazole (unlicensed indication) 400mg once daily for three days. Albendazole is contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding[5]

.

Ivermectin use should be avoided in children weighing less than 15kg and/or aged under five years. Albendazole dose should be reduced to 200mg in children weighing less than 10kg[5]

.

Trichuris trichiuria

, or whipworm, causes trichururiasis. Most patients are asymptomatic, however, heavy infestations may cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms such as colitis and dysentery. Iron deficiency anaemia is common in children on poor diets and chronic infections in children could cause growth retardation. Severe dysentery could cause rectal prolapse but this is rare.

A positive diagnosis of whipworm can be made easily in children presenting with rectal prolapse. In other patients, stool microscopy and full blood counts are useful, with eosinophilia likely present in blood counts. Albendazole (unlicensed) 400mg can be given twice daily for three days, but should be avoided in children aged under two years. Mebendazole 500mg can be given as an immediate dose in adults, and in children aged 1–18 years, 100mg can be given twice daily for three days[5],[6]

. Albendazole and mebendazole are contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Photo guide: Helminth pathologies

Source: Wikimedia Commons

1) Cutaneous Larva Migrans

2) Lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis)

3) Schistosomiasis (swimmers itch) shows parasite entry on skin

Echinococcus granulosus and

Echinococcus multilocularis

cause echinococcosis (Hydatid disease), common in central and Eastern Europe (see Photo guide: Helminth parasites’).

Patients presenting with primary infection are often asymptomatic. Latent infections may present years later with symptoms caused by mass effect within organs, obstruction of blood or lymphatic flow, or complications such as rupture or secondary bacterial infections. Fever and acute hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, may be the principal manifestations of cyst rupture.

Imaging, including ultrasound, CT scan and MRI, are useful diagnostic techniques. Serology testing with ELISA (or other techniques) can also be performed to confirm presence of hydatid disease.

Treatment of hydatid disease varies according to cyst type and the approach should be discussed with an expert. Alveolar echinococcosis caused by E.

multilocularis is usually fatal if untreated. Surgery or puncture, aspiration, injection, and re-aspiration (PAIR) using protoscolicide (such as 95% ethanol) could be considered in some patients[5]

.

Albendazole (unlicensed) 400mg twice daily can be given to adults aged over 18 years. Albendazole is contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding and patients should be advised to use a barrier method for contraception during treatment and for one month after treatment because hormonal contraception can fail and albendazole is teratogenic[5]

. Children aged over two years can be given albendazole 7.5mg/kg twice daily (maximum of 400mg twice daily)[6]

. If undergoing surgery or PAIR, patients aged over 18 years can be given praziquantel (unlicensed) 20mg/kg twice daily for 14 days before and after the procedure. If cyst rupture is suspected, both drugs should be used at the same dose[5]

.

Filariasis is caused by filariae nematode parasites and of the hundreds described, only eight filarial parasites cause disease in humans. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified LF as the second leading cause of permanent and long-term disability in the world, after leprosy. The cutaneous group includes Loa loa, Onchocerca volvulu s and Mosonella streptocerca. The lymphatic group includes Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi and Brugia timori and the body cavity group includes Mansonella perstans and Mansonella ozzardi. In the UK, filariasis is seen in patients arriving from sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, many of the Pacific islands and focal areas of Latin America and the Caribbean (including Haiti). B. malayi occurs mainly in China, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and various Pacific islands. B. timori occurs on the Timor Island of Indonesia.

In endemic areas, up to 70% of infected patients are asymptomatic[15]

. Patients with LF often present with fever, inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy and males can present with testicular and inguinal pain. Skin exfoliation is common. In instances of limb or genital swelling, repeated episodes of inflammation and lymphoedema lead to lymphatic damage, chronic swelling and elephantiasis of the legs, arms, scrotum, vulva and breasts (see ’Photo guide: Helminth pathologies’).

Patients may experience syndromes that include: acute adenolymphangitis (ADL) with symptoms of fever and painful lymphadenopathy; filarial fever without associated adenitis and no lymphadenopathy; and tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE), with symptoms of dry paroxysmal cough, wheezing, shortness of breath, malaise and weight loss associated with a high eosinophil count.

Onchocerciasis

often presents in patients as a clinical triad of infection, which includes dermatitis (skin lesions include oedema, pruritus, erythema, papules, scab-like eruptions, altered pigmentation and lichenification), skin nodules (or onchocercomas, which are common over bony prominences) and ocular lesions, which are usually related to the duration and severity of infection, caused by the host’s immune response to microfilariae. Loss of visual acuity may occur.

Loiasis (African eye worm), is transmitted by the bite of Chrysops fly, which is endemic in West and Central Africa. The majority of patients with loiasis are asymptomatic. Calabar swelling (transient subcutaneous swelling) can occur on account of hypersensitivity related to migration of the adult worm or release of microfilariae, and often resolves spontaneously in two to four days. Patients may also experience migration of the worm across the conjunctiva.

Mansonella

infections are usually asymptomatic. Fever, pruritus, skin lumps, lymphadenitis and abdominal pain are common.

Filariasis is suspected in those with epidemiologic exposure, consistent clinical findings and supporting laboratory findings. Microfilariae can be detected through examination of the following:

- Blood: microfilariae of all species that cause lymphatic filariasis and the microfilariae of Loa loa, M. ozzardi and M. perstans are detected in blood;

- Urine: if lymphatic filariasis is suspected, urine should be examined macroscopically for chyluria, then concentrated to examine for microfilariae;

- Skin: O.

volvulus and M. streptocerca diagnosed when microfilariae are detected in multiple skin snip specimens from different sites located on both sides of the body; - Eye: microfilariae of O. volvulus may be detected in the cornea or anterior chamber of the eye using slit lamp examination.

Imaging techniques are also of use in diagnosis. Chest X-ray can be used to identify diffuse pulmonary infiltrates in patients with TPE. Ultrasound can be used to monitor lymphatic obstruction, and occasionally to demonstrate adult worms. Lymphoscintigraphy could also be used as an alternative. Serology testing with ELISA can also be performed.

Ivermectin (unlicensed) 150–200µg/kg is the treatment of choice for onchocerciasis in adults aged over 18 years. Two further doses should be given at monthly intervals, repeated after three to six months as needed, usually for several years; plus doxycycline 200mg once daily for six weeks[5]

.

Albendazole (unlicensed) 400mg twice daily should be given to patients aged over 18 years with W. bancrofti for 21 days for lymphatic filariases and 200mg twice daily for 21 days for Loa loa; plus ivermectin dosage as for onchocerciasis[5]

.

For Loa loa, diethylcarbamazine (unlicensed) should be given 50mg once daily for the first day, increasing as tolerated to 50mg three times daily on the second day, 100mg three times daily on the third day, then 200mg three times daily, for a total of 21 days at that dose in adults aged over 18 years. Oral steroids should be included for microfilaraemic patients aged over 18 years with loiasis; four-day course of oral prednisolone 20mg once daily, one day before diethylcarbamazine[5]

.

For M. perstans, patients aged over 18 years should be given doxycycline 200mg once daily for six weeks[5]

.

Preventative chemotherapy

The WHO recommends preventive chemotherapy as a public health strategy in endemic areas. Antihelminthics used alone, or in combination, prevent morbidity, usually covering multiple helminths at a time, and contribute towards a sustained reduction in transmission[16]

. Since many antihelminthics are broad-spectrum, allowing several helminths to be tackled simultaneously, preventive chemotherapy interventions are drug-based rather than disease-based, with emphasis on the best use of available drugs rather than specific infections. The greatest challenge is reaching all at-risk individuals; preventive chemotherapy should begin early in life, and every opportunity should be taken to reach at-risk populations[16]

. For advice to give to people travelling to areas where helminthic infections are prevalent, see ‘Prevention advice’.

Prevention advice

The following prevention advice should be given to all patients travelling to areas where helminthic infections are prevalent:

- Contaminated food and water pose an infection risk; take adequate hygiene and food and water precautions.

- Wash hands with soap and water before eating, after using the bathroom, and after direct contact with pre-school aged children, animals or faeces.

- Avoid eating salads, unpeeled raw fruits and uncooked vegetables; only eat food that is served hot and fully cooked, and fruit that has been washed in clean water, then peeled. Unless known to be safe, avoid using tap water for drinking, preparing food and beverages, making ice, cooking, brushing teeth, and avoid contact with the mouth during showering or bathing.

- Avoid contact with water that may be contaminated with sewage, faeces or wastewater runoff; near storm drains; after heavy rainfall; or in freshwater of schistosomiasis-endemic areas in the Caribbean, South America, Africa and Asia.

- To prevent hookworms, avoid walking barefoot in areas where hookworm is common or there may be human faeces-contaminated soil. To protect from bites, diethyltoluamide (DEET)-containing insect repellent, permethrin-soaked clothing, and thick, long-sleeved, long-legged clothing should be worn.

Lucy Hedley, MPharm, MRPharmS, MFRPSI, PGDipGPP, is senior clinical pharmacist HIV/GUM & infectious diseases, University College London NHS Foundation Trust.

Robert L Serafino Wani MBBS, MRCP, FRCPath, MSc (Trop Med), SCE (ID) specialty trainee in infectious disease & microbiology/virology, Hospital for Tropical diseases, University College Hospital, London.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Global Atlas of Helminth Infections. Available at: www.thiswormyworld.org/worms/global-burden (accessed October 2015).

[2] Crompton DW & Nesheim MC. Nutritional impact of intestinal helminthiasis during the human life cycle. Ann Rev Nutr 2002;22:35–59. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.120501.134539

[3] Baron S. Medical Microbiology, 4th Edition. The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7627/ (accessed October 2015).

[4] Gill GV & Beeching N. Lecture Notes: Tropical Medicine, 6th Edition. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

[5] University College London Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Diagnosis and Treatment of Tropical Infections Clinical Guidelines, September 2012.

[6] British National Formulary for Children (BNFC). August 2015. Available at: www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/bnfc/current/index.htm

[7] Khuroo MS. Ascariasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996;25(3):553–557. doi:10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70263-6

[8] Won KY, Kruszon-Moran D, Schantz PM et al. National seroprevalence and risk factors for Zoonotic Toxocara spp. infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008;79:552. PMID: 18840743

[9] Botero D, Tanowitz HB, Weiss LM et al. Taeniasis and cysticercosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1993;7(3):683–697. PMID: 8254166

[10] Kaushal S, Rani A, Chopra SC et al. Safety and efficacy of clobazam versus phenytoin-sodium in the antiepileptic drug treatment of solitary cysticercus granulomas. Neurol India 2006;54(2):157–160. PMID: 16804259

[11] McCann CM, Baylis M & Williams DJ. The Veterinary Record, 4 June 2005.

[12] NHS choices. Schistosomiasis (bilharzia). Available at: www.nhs.uk/Conditions/schistosomiasis/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed October 2015).

[13] Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A et al. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop 2000;77(1):41–51. doi:10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00122-4

[14] Tukahebwa EM, Magnussen P, Madsen H et al. A very high infection intensity of Schistosoma mansoni in a Ugandan Lake Victoria Fishing Community is required for association with highly prevalent organ related morbidity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7(7):e2268. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002268

[15] Kazura J, Guerrant R, Walker DH, Weller PF, eds. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone;1999;2:852.

[16] World Health Organization. Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: coordinated use of anthelminthic drugs in control interventions: a manual for health professionals and programme managers, 2006. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43545/1/9241547103_eng.pdf (accessed October 2015).