Shutterstock

Learning outcomes

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Identify common sources of insect bites and stings;

- Recognise the signs and symptoms of an insect bite or sting, including symptoms that require referral;

- Recommend pharmacological and non-pharmacological options to manage symptoms;

- Discuss ways to reduce the likelihood of insect bites and stings.

Introduction

Being stung or bitten by an insect is almost an inevitability, with estimates suggesting it happens in up to 94% of the population at least once during their lifetime[1]. Reactions to bites and stings range from mild localised reactions that last a few hours to medical emergencies, such as anaphylactic reactions[1]. Insects generally sting or bite either as part of their feeding routine or as a defence mechanism; species commonly encountered in the UK include spiders, bees, wasps, horseflies, ticks, fleas and mites[1]. Mosquitoes are present in the UK but are less likely to spread malaria than those found in endemic areas, which is why travel to endemic areas requires suitable prevention and prophylaxis[2].

Most bites and stings are not serious and will heal within a few hours or days. For infected bites, community pharmacies participating in minor ailment services (such as Pharmacy First in England, Pharmacy First Scotland and the Welsh Common Ailments Service) are able to supply antibiotics under patient group directions to patients meeting eligibility criteria.

This article will cover the symptoms pharmacists should be aware of, how bites and stings are diagnosed, considerations for their pharmacological management and self-care advice to provide to patients.

Causes and risk factors

The true prevalence of bites and stings is difficult to measure as many people will either self-manage or seek treatment through their community pharmacy. Although a study of GP consultations suggests that bites are more common in women, particularly from the age of 15 years upwards, bites and stings can occur in anyone of any age[3].

Increased exposure to insects increases the likelihood of being bitten or stung, therefore those working with insects and owners of pets, such as cats and dogs, are at increased risk. Being outdoors with exposed skin increases risk[1].

Symptoms

The pain initially experienced when being bitten or stung comes from the physical action itself and, in some cases, the venom injected. Other symptoms, such as localised inflammation, occur following the body’s immune response to saliva from the insect feeding at the wound site[1]. Specifically with bites, the first exposure generally leads to no reaction, with subsequent bites stimulating type IV immune responses, developing 8–12 hours following the bite and, with continued exposure to the allergen, a type 1 reaction occurring within 20 minutes of the bite; this can lead to anaphylactic reactions[1].

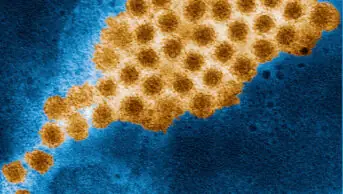

Localised symptoms of bites and stings include inflammation, erythema, itching and pain at the site[1]. If it has not already been removed, the stinger or insect’s mouthparts may be visible. Figure 1 illustrates the appearance of an insect bite:

JANE SHEMILT / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The NHS UK web page for insect bite and sting symptoms shows a variety of images representing the presentation of the skin following a bite or sting from a variety of insects and should be consulted to help familiarise yourself with the varying presentations. See ‘Useful resources’.

Systemic reactions are more common following wasp stings than bee stings, with systemic reactions being rare following an insect bite. Mild reaction symptoms include urticaria (hives and wheals, i.e. swelling of the skin’s surface into red- or skin-coloured welts) and angio-oedema (i.e. swelling in the local area), with more severe symptoms including bronchospasm, upper-airway obstruction, hypotension and seizures[1]. In addition, some patients will present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea[1].

Diagnosis

Other conditions with a similar presentation to insect bites and stings include infections of the skin such as cellulitis (see ‘Complications’), tumours, dermatitis, chicken pox and urticaria[1]. Differentiating between these conditions relies on a combination of history-taking and physical examination. Table 1 shows the important elements to gather as part of history-taking:

Responses that would necessitate referral to primary or secondary care are:

- Fever;

- Flu-like symptoms;

- Erythema migrans rash (round/oval rash with a target-like appearance) appearing more than 48 hours after a tick bite;

- Previous allergic reaction to an insect bite or sting;

- Travel to malaria-endemic area within previous 12 months;

- Bite or sting to mucosal membranes, the mouth, eyes or throat;

- Jaundice;

- Angio-oedema;

- Signs of a systemic reaction, such as hypotension, diarrhoea, vomiting, seizure, difficulty breathing, airway compromise and swelling of mucous membranes;

- Collapse or loss of consciousness[1].

Further investigation is not normally required if the diagnosis of a simple insect bite or sting is made.

Complications

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is an acute bacterial skin infection, commonly caused by streptococci and staphylococci[4]. If the site of the bite or sting becomes infected, symptoms include pain, warmth around the infection site, swelling and erythema[4]. Erythema presents as a reddened area on lighter skin tones and as a grey ‘ashen’ or darker brown region on darker skin tones[5]. The lower limbs are the most common site of infection and suspected cellulitis in this area must be differentiated from deep vein thrombosis using an assessment such as Wells Score; however, other areas of the body such as the upper limbs and face can be infected[4].

Figure 2 shows the appearance of cellulitis in different skin tones. More information on how skin conditions may present differently in different skin tones can be found in ‘Recognising common skin conditions in people of colour’.

Lyme disease

Lyme disease is a zoonotic infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted to humans through tick bites[6]. Tick infestation is common at ground level in woodlands, so avoiding exposing the skin when walking through woodlands is an important step to reduce the likelihood of being bitten[1].

In most cases, symptoms include the presence of an erythema migrans rash, although this is not always the case[6]. The rash can be differentiated from cellulitis as it does not present as warm to the touch, itchy or painful; it can also be differentiated from a generalised local reaction to the bite as a generalised rash usually presents within 48 hours, whereas erythema migrans occurs at least 3 days, but usually 1–4 weeks, after being bitten[6]. The rash has a characteristic ‘bull’s eye’ or ‘target-like’ appearance as shown in Figure 3.

Shutterstock.com

Patients may also present with other symptoms, such as fatigue, headache, fever, malaise and inflammatory arthritis[6]. The type and severity of these symptoms determine when and how the condition should be treated. Treatment involves the use of antibiotics and patients should be advised that even with successful treatment, they may still experience symptoms for months or more than one year after finishing treatment[6].

Malaria

Malaria is a life-threatening condition transmitted to humans through being bitten by female Anopheles mosquitoes[7]. Symptoms include fever, headache, malaise, gastrointestinal symptoms, flu-like symptoms and confusion[7,8]. Malaria symptoms can start as early as seven days after entering an endemic area, such as large areas of Africa and South Asia, and it should be considered as a possible diagnosis for up to one year after travel to these areas[8]. Those planning travel to an endemic area should be counselled on suitable protection, such as the use of insect-repellent products and nets and, where indicated, should be sold or prescribed malaria prophylaxis. Anyone with suspected malaria should be referred to A&E as a matter of urgency[7]. Treatment involves the use of antimalarial drugs. Guidance relating to malaria prophylaxis and treatment are available from the UK Health Security Agency website; see ‘Useful resources’.

Management

As most bites and stings are self-limiting, with symptoms generally resolving within a couple of hours, the mainstay of treatment is simple first aid to keep the wound clean, with a cold compress used to help reduce inflammation[1]. The wound should be washed with warm, soapy water and allowed to dry. An antiseptic can then be applied to the area around the bite or sting[1]. There is limited evidence of benefit to support the use of antihistamines, steroid creams and analgesics, with use generally off label; however, these medicines may be of some benefit in the management of symptoms, such as itching and mild pain, so should not be dismissed completely[1].

Removal of the sting

The first step in managing a sting is to ensure the sting itself has been removed if it is still present at the site. This should be done in a sideways motion using a blunt, flat implement, such as a fingernail or credit card, taking care not to burst the venom sac[1].

Removal of ticks

If the tick is still present and visible following the tick bite, the tick should be removed immediately. Tick removal devices are available, but tweezers or forceps (if available) can also be used. To reduce the risk of leaving the mouth pieces in place and release of further contaminants into the wound, the tick should be gripped as close as possible to the skin and removed by pulling perpendicular to the skin[1].

Antihistamines

Oral antihistamines — such as chlorphenamine, cetirizine and loratadine — may be of benefit in helping patients manage symptoms of itching[9–11]. Chlorphenamine can cause drowsiness as a side effect; however, some patients may experience drowsiness with cetirizine or loratadine too[9–11]. It is therefore important to discuss with the patient whether potential drowsiness would be an issue for them and, where appropriate, to advise them not to drive or operate machinery if they feel drowsy[9–11].

In the UK, chlorphenamine can be sold over the counter (OTC) for use in patients aged 1 year upwards and prescribed for those aged 1–12 months (use in this age group is off label)[9,12]. Chlorphenamine should be given at a dose of 4mg every 4–6 hours up to a maximum of 24mg daily in those aged 12 years and over[9]. For children, dosing is dependent on age.

Cetirizine can be sold OTC or prescribed from the age of 2 years. The recommended dose for those aged 12 years and above is 10mg once daily, with lower doses used in those under 12 years[10,13].

Loratadine can be sold OTC or prescribed to patients aged 2 years upwards. The recommended dose is 10mg once daily[11,14]. A lower dose of 5mg once daily is used for patients aged 2–11 years with a body weight of less than 31kg[11].

The use of topical antihistamines and antipruritics, such as crotamiton, should be recommended with caution owing to lack of evidence of benefit and the risk of topical products causing localised systemic reactions themselves[1].

Corticosteroids

A mild topical corticosteroid, such as hydrocortisone 1% cream, is an alternative to antihistamines for managing itching in uncomplicated stings and bites. Topical hydrocortisone is not licensed OTC for use on the face, anogenital region, or on broken or infected skin in patients of any age, or for any location in children aged under 10 years; however, it can be prescribed to treat inflammatory conditions, such as eczema, in these areas. Hydrocortisone should not be sold for use by pregnant women[15]. Patients should be advised to use the cream once to twice daily, following the fingertip unit method when determining how much cream to apply[15].

Corticosteroids can be used in the management of a larger, localised reaction; however, this is usually off-label and should be avoided if the site is infected[1].

Analgesia

Simple analgesia with paracetamol or ibuprofen can be considered in line with their product licences (if sold OTC); however, if stronger pain relief is required the patient should be referred for further investigation as this could suggest an infection or other underlying cause[1]. Dosage is dependent upon age.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics should not be used routinely in the management of simple bites and stings; however, they are used in the management of complications associated with them, such as cellulitis and Lyme disease.

Antibiotics such as flucloxacillin, clarithromycin and erythromycin can be supplied under minor ailment services where the patient is experiencing symptoms such as localised erythema and swelling, pain or tenderness, and the area surrounding the bite or sting is hot to the touch[16]. Symptoms need to have been present or worsening for at least 48 hours following the bite / sting for the patient to be eligible[16]. More severe symptoms suggesting systemic infection, such as the patient experiencing fever or being systemically unwell, require urgent referral for further investigation. Pregnant patients, children aged under one year and patients who are immunocompromised are ineligible for antibiotic treatment under Pharmacy First and must be referred[16].

Adrenaline auto-injectors

In secondary care, patients who have experienced anaphylactic allergic reactions should be prescribed adrenaline auto-injectors to keep with them at all times. Each time the device is dispensed, patients should be counselled on how to administer the device and advised on safe storage and how to reorder a prescription through their primary care provider before the device is due to expire or if one or more of the pens have been used. This is to ensure the patient knows how to use the device in an emergency and is particularly important when changing brands. Training videos on how to administer adrenaline auto-injectors can be accessed through the Electronic Medicines Compendium by searching for the brand being prescribed or dispensed. See ‘Useful resources’.

General advice

Patients should be advised not to scratch the wound as this will increase the risk of infection if the skin becomes broken. As part of management within the primary care setting, the need for tetanus prophylaxis should be considered if the site of the bite or sting is likely to have been contaminated by soil or manure, depending on the patient’s vaccination status[1,17]. For bedbug bites, advise the patient to contact the local pest control service if infestation is suspected, and for flea bites, if the patients’ pets are the suspected host, advise them to examine their pets and treat them with suitable flea treatment accordingly[1]. The house may also need treating if fleas are spotted within the house or on furnishings.

Reducing the likelihood of insect bites and stings

There are measures that can be taken to reduce the likelihood of bites and stings. The use of insect-repellents containing diethyltoluamide (DEET) should be considered; DEET-containing products are available in various percentages, with 50% the highest and percentages below 20% not recommended, and are suitable from the age of 2 years[9]. Pregnant women can use DEET-containing products but should use lower percentages, such as 20–30%[8].

Box 1 summaries important advice to provide to help reduce the likelihood of bites and stings:

Box: Advice to reduce likelihood of bites and stings

- Wear suitable clothing to keep the skin covered if going through an area likely to be populated by insects;

- Avoid wearing bright colours and floral prints as these are attractive to insects;

- Avoid walking barefoot or wearing sandals when outside;

- Wearing boots and tucking trousers into socks should be considered when walking through woodland as these may be populated by ticks. Shower and check clothes for ticks when you get home;

- Perfumes, deodorants and other personal hygiene products with strong scents should be avoided;

- If eating outside, check straws, cups and other food vehicles for insects before eating/drinking from them;

- Employ trained professionals to deal with any insects’ nests — they will have appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and access to suitable products to safely deal with the nest;

- Wear appropriate PPE if working with insects that bite or sting;

- Insecticide products that can be used to kill stinging insects from a distance, such as sprays, can be used to avoid being stung;

- Consider the use of insect-repellent products containing DEET; however, these will not help in repelling stinging insects;

- For those with domestic pets, ensure that flea and tick prevention treatments are kept up to date.

Case studies

Case 1

Consultation

A 38-year-old male has come into the pharmacy for some advice after his 7-year-old daughter was stung on the back of the neck by a wasp while playing in the park. The child appears upset but is not showing any signs of anaphylaxis. The father removed the sting using his fingernail but wants to know if there is anything else he should do.

Assessment/diagnosis

You examine the area where the child has been stung. It is inflamed and red, but the inflammation is localised to the area; the child tells you it is itching and is “a little bit” painful. Upon questioning, the father informs you that his daughter has never been stung before and has no history of anaphylaxis; she has no medical history of note, is not currently using any medication and has no known allergies.

Advice

In this case, simple first aid is recommended[1]. A topical antiseptic should be used to clean after washing of the area with soap and water, and an oral antihistamine (such as chlorphenamine) can be recommended to help with the itching. It is recommended that 2mg should be given every four to six hours when needed, with a maximum of 12mg per day[9]. Use of a cold compress at the site of the sting should be recommended to help with the pain and swelling. Although the evidence of benefit is limited, consideration should be given regarding the need for an analgesic, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, to help with the pain. The father should be advised to monitor for signs of anaphylaxis and to take the child to A&E if she develops a rash, swelling of the tongue or experiences difficulty breathing.

Case 2

Consultation

A 27-year-old woman attends her local community pharmacy seeking advice. She explains that she has noticed a rash on the back of her leg and has not felt well since yesterday. She has recently adopted a dog and took it for a walk in the woodlands near their house last week and remembers being bitten by an insect, which she managed to brush off.

Assessment/diagnosis

The patient shows you the back of her leg and you see an oval area of inflammation with a slightly raised border. Upon questioning, the patient informs you that she thinks it was about ten days ago that she was bitten but she does not know what type of insect it was. She only noticed the area of inflammation yesterday and doesn’t think it has been present for more than a day or two. The site on her leg is not itchy, hot or painful, but she has had a headache and has felt nauseous since yesterday.

The patient has no medical conditions and is currently taking desogestrel as an oral contraceptive. She has no known allergies and is not currently pregnant or breastfeeding.

An infected flea bite is a possibility, although is a less likely diagnosis based on the information provided. As the rash is characteristic of erythema migrans and the patient feels unwell, the overall picture is suggestive of Lyme disease.

Advice

Lyme disease requires further investigation and, if this diagnosis is made, the initiation of antibiotic treatment. The patient should therefore be referred to her local primary care provider as soon as possible. If Lyme disease is diagnosed, treatment with either doxycycline or amoxicillin will be commenced and given for a course of 21 days[6]. The patient should be advised that symptoms may persist for some time following successful treatment and she should be provided with advice on how to avoid future bites, such as wearing clothing to cover the skin when walking through areas where ticks are likely, including woodland, and to shower after walking through these areas [6].

Case 3

Consultation

A 38-year-old man attends the primary care centre where you are working as the pharmacist independent prescriber. He has come to see you as he has noticed an area of swelling above his left ankle, present since yesterday, which has started to spread up his leg. The patient explains that he was cutting the grass a couple of days ago and initially noticed a small red lump that was itchy so assumed he had been bitten. He put some antiseptic cream on it at the time and this helped, but he is concerned that the redness is spreading and would like your advice.

The patient has no medical conditions, is not taking any medication currently and he has no known drug allergies.

Assessment/diagnosis

The patient advises that the area is no longer itchy but feels warm and tender to the touch. He has had no recent foreign travel or surgery. The patient’s temperature is 37.8oC.

As the presenting complaint is within your scope of practice, you perform a Wells’ score to assess for deep vein thrombosis and determine this to be an unlikely diagnosis. Based on the presenting symptoms, this would be considered a non-severe case of cellulitis (class I), secondary to the insect bite.

Advice

At this stage, further investigation is not recommended; however, antibiotic treatment should be started[4]. The antibiotic to prescribe will depend on local sensitivities, with flucloxacillin generally recommended first line, with clarithromycin or doxycycline as the alternative for penicillin-allergic patients[4,18]. For this patient, a five-day course of oral flucloxacillin at a dose of 1g every six hours would be appropriate[18]. In addition to counselling on when and how to take flucloxacillin, the patient should be advised to return to the primary care centre if there has been no improvement in symptoms after two to three days or if symptoms worsen; to help monitor changes in the spread of the infection, an outline should be drawn on the skin using a marker pen[4].

The patient should also be advised to drink plenty of fluids, keep the leg elevated if they experience any oedema, and to use simple analgesia (such as ibuprofen or paracetamol) if they experience any pain[4].

Best practice

- Reactions to most bites and stings are self-limiting and tend to clear within a couple of hours;

- The sting or any mouth parts should carefully be removed immediately;

- Good hygiene around the affected area is necessary to reduce the risk of infection. The skin should be washed with soap and water, allowed to dry, and an antiseptic applied to the local area;

- A cold compress may be helpful in reducing localised swelling;

- The evidence of benefit for the use of antihistamines, corticosteroid creams and analgesics is limited, however may be helpful in managing symptoms;

- Any patient with a history, or demonstrating signs of, anaphylaxis should be referred to A&E immediately;

- Patients with a history of anaphylaxis should always carry an adrenaline auto-injector with them and receive counselling on appropriate use;

- There are simple steps that can be taken to reduce the likelihood of insect bites and stings, such as covering the skin and use of insect repellent sprays containing 20–50% DEET[1].

Useful resources

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc;

- NHS UK: Insect bites and stings symptoms. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/insect-bites-and-stings/symptoms/;

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Cellulitis – acute. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cellulitis-acute/;

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Insect bites and stings. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/insect-bites-and-stings/;

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Lyme disease. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/lyme-disease/;

- PAGB OTC Directory. Available at: https://www.otcdirectory.co.uk/;

- UK Health Security Agency. Malaria: guidance, data and analysis. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/malaria-guidance-data-and-analysis;

- MHRA advice on adrenaline auto-injectors. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vNR5N1-iBw.

This article has been updated by The Pharmaceutical Journal team and reviewed by the expert authors to ensure it remains relevant and up to date, following its original publication in June 2023.

- 1Clinical knowledge summaries: insect bites and stings. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/insect-bites-stings/ (accessed June 2023)

- 2Insect bites and stings. NHS. 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/insect-bites-and-stings/ (accessed June 2023)

- 3Elliot AJ. The association between impetigo, insect bites and air temperature: a retrospective 5-year study (1999-2003) using morbidity data collected from a sentinel general practice network database. Family Practice. 2006;23:490–6.

- 4Clinical knowledge summaries: cellulitis – acute. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2023. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cellulitis-acute/ (accessed June 2023)

- 5Sangha AM. Dermatological Conditions in skin of colour: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:S20–2.

- 6Clinical knowledge summaries: lyme disease. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2022. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/lyme-disease/ (accessed June 2023)

- 7Clinical knowledge summaries: malaria. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/malaria/ (accessed June 2023)

- 8Blenkinsopp A, Duerden M, Blenkinsopp J. Symptoms in the Pharmacy: A guide to the management of common illnesses. Malaria prevention. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell 2023.

- 9Chlorphenamine. British National Formulary. 2023. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/chlorphenamine-maleate/ (accessed June 2023)

- 10Cetirizine. British National Formulary. 2023. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/cetirizine-hydrochloride/ (accessed June 2023)

- 11Loratadine. British National Formulary. 2023. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/loratadine/ (accessed June 2023)

- 12Piriton Syrup Patient Information Leaflet. Medicines Complete. 2023. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3928/pil (accessed June 2023)

- 13Zirtek Allergy Solution 1mg/1ml Patient Information Leaflet. Medicines Complete. 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6752 (accessed June 2023)

- 14Clarityn Allergy 1mg/1ml Syrup Patient Information Leaflet. Medicines Complete. 2018. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/13696 (accessed June 2023)

- 15Hydrocortisone. British National Formulary. 2023. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/hydrocortisone/#exceptions-to-legal-category (accessed June 2023)

- 16Infected insect bites patient group directions. Supply of flucloxacillin capsules/oral solution/oral suspension for the treatment of infected insect bite(s) and sting(s) under the NHS England commissioned Pharmacy First service. NHS England. 2025. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/PRN01010-4a.-infected-insect-bites-flucloxacillin-patient-group-direction-pharmacy-first.pdf (accessed January 2026)

- 17Tetanus: advice for health professionals. Public Health England. 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tetanus-advce-for-health-professionals (accessed June 2023)

- 18Cellulitis. University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust: Adult Antimicrobial Guide v3.65. 2023. Available through Microguide (accessed June 2023)

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You might also be interested in…

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control

A very useful guide which is up to date and will help to reduce unnecessary demands for antibiotic scripts

SHENU BARCLAY LOCUM PHARMACISTGLOUCESTERSHIRE