DR P. MARAZZI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Hepatitis A (HAV) is a viral infection of the liver, but unlike hepatitis B and hepatitis C, hepatitis A is generally self-limiting and does not cause chronic disease[1]

. However, for a small number of patients (less than 1% of those infected), hepatitis A can have fatal consequences as a result of the development of fulminant hepatitis (significant necrosis of the liver) and acute liver failure[2]

.

Infection with HAV confers lifelong immunity and is preventable with vaccination. The World Health Organization estimates that hepatitis A caused around 7,134 deaths worldwide in 2016, accounting for 0.5% of the total mortality from viral hepatitis[2]

.

This article describes the main preventative strategies for hepatitis A, as well as how pharmacists can support symptomatic patients.

Transmission

HAV is an RNA virus that is primarily spread via the faecal–oral route. Infection generally occurs following ingestion of food or water that has been contaminated with the faeces of an infected person, although it can also occur via close person-to-person contact[1],[2]

. The disease is most prevalent in areas with inadequate sanitation, where it can be difficult to maintain good personal hygiene.

Other routes of transmission include sexual transmission (particularly in men who have sex with men [MSM]), blood transfusions and through the sharing of illicit drug paraphernalia[2]

.

HAV is relatively resistant to freezing, low pH and inactivation by moderate heating, as well as to many chemical and physical agents. Therefore, it can survive on environmental surfaces, human skin, food items and sewage, facilitating the transmission of infection[3]

.

Epidemiology

In developing countries with poor sanitation and hygiene practices, 90% of children are infected with HAV before the age of ten years and most do not experience any noticeable symptoms[2]

. In these areas, epidemics are an uncommon occurrence, as older children and adults tend to be immune as a result of prior infection in childhood.

Conversely, in developing countries with transitional economies (i.e. changing from a centrally planned economy to a market economy), sanitary conditions can be variable, so children often escape infection in childhood. Many reach adulthood without having developed immunity, leading to large outbreaks in the older age groups[2]

.

Infection with HAV is seen infrequently in developed countries. Outbreaks of infection may still occur, particularly among adolescents and adults in high-risk groups, such as injecting drug users, MSM, people returning from areas of high endemicity, and in isolated populations, such as closed religious communities[3]

. Better levels of hygiene in developed countries limit person-to-person transmission of the virus and, as a result, these outbreaks tend to be short-lived.

During 2017, there were 942 confirmed reports of HAV infection in England and Wales, and around 30% of infections were in people in the 25–34 years age group[4]

. This increase from 444 cases in 2016 was attributed to the outbreak of HAV the MSM population[4],[5]

.

Diagnosis

The average incubation period of hepatitis A is between 28 and 30 days, with a range of 15 to 50 days[6]

.

HAV replicates in the liver and is shed in high concentrations in faeces, with peak concentrations being reached two weeks before symptomatic presentation through to one week after the onset of clinical illness[7]

. Individuals with hepatitis A are infectious during the incubation period and remain contagious for around one week after the onset of symptoms.

Symptoms

Infection with HAV generally leads to an acute, self-limiting illness[1]

.

The presenting symptoms, which are not easily distinguishable from other types of viral hepatitis, include:

- Abdominal pain;

- Anorexia;

- Arthralgia (i.e. pain in a joint);

- Dark-coloured urine;

- Diarrhoea;

- Fever;

- Hepatomegaly (i.e. abnormal enlargement of the liver);

- Jaundice;

- Loss of appetite;

- Malaise;

- Nausea;

- Pale stools;

- Pruritus (i.e. severe itching of the skin).

Not everyone infected with HAV will present with all the symptoms outlined above and clinical outcome is strongly associated with age. For example, in children aged under six years, most infections are asymptomatic; if illness does occur, it is not usually accompanied by jaundice[7]

. Children aged six years and older and adults are more likely to present with signs and symptoms, and have a greater risk of developing fulminant liver failure[7]

. In all patient groups, HAV can cause fulminant hepatitis, with a reported incidence of 0.015–0.500%

[8]

.

Although hepatitis A resolves spontaneously in more than 99% of the cases, although relapse of symptoms has been reported in up to 20% of patients[8]

. This relapse occurs when a person who has recovered experiences another acute episode several weeks after their initial presentation. Recovery from HAV infection should occur within 24 weeks[8]

.

Cholestatic hepatitis can also occur with HAV infection and is characterised by a protracted period of jaundice lasting for more than three months with associated pruritus, weight loss, diarrhoea and malaise[9]

. This typically resolves without intervention within 12 weeks with no lasting effects[9]

.

Several extrahepatic manifestations of HAV have also been reported; these tend to occur most commonly in patients who have experienced a protracted disease course (see Box 1).

Box 1: Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis A infection

- Aplastic anaemia (i.e. when the body stops producing enough new blood cells);

- Arthritis;

- Cryoglobulinaemia (i.e. a form of vasculitis);

- Glomerulonephritis (i.e. damage to the glomeruli);

- Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (i.e. inflammation of small blood vessels);

- Myocarditis (i.e. inflammation of the myocardium);

- Thrombocytopaenia (i.e. abnormally low levels of platelets);

- Transverse myelitis (i.e. an inflammation of both sides of one section of the spinal cord)[8],[9],[10]

,[11]

,[12]

,[13]

,[14]

.

Investigations

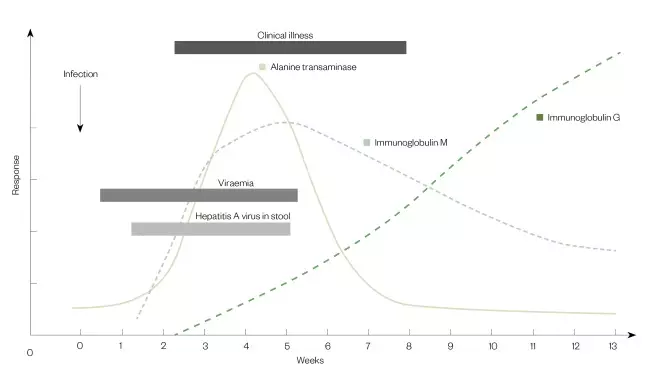

A definitive diagnosis of HAV infection is usually based on the detection of specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to the virus (IgM anti-HAV) in the patient’s blood. These antibodies are detected in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. IgM anti-HAV should be interpreted alongside immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-HAV as described below. The presence of HAV RNA is definitive of an acute HAV infection.

In symptomatic patients, IgM anti-HAV appear within 5 to 10 days of the development of symptoms and clinical illness. The development of antibodies correlates with the peak increase in liver enzymes and typically persists for four months, with a range of 30 to 420 days[10]

. IgG anti-HAV appears simultaneously and dominates the antibody response, persisting for several years, if not indefinitely, and confers lifelong immunity. HAV RNA can be detected in both stools and blood at the time of presentation with acute infection. The presence of IgG anti-HAV in the absence of IgM anti-HAV indicates prior infection or vaccination only.

In cholestatic hepatitis, laboratory findings include elevations in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, with significantly raised aminotransaminases of between 5 times and 15 times the upper normal limit. In view of the cholestasis, ultrasonography is a necessity to exclude coexistent biliary obstruction[10]

.

Very rarely, HAV infection may act as a trigger for the development of autoimmune hepatitis — a chronic hepatitis that is associated with the presence of circulating autoantibodies and characteristic findings on liver histology[11],[12]

(see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The typical course of hepatitis A infection

The highest levels of hepatits A virus are found in the stool, with peak levels occuring in the two weeks before onset of illness.

Source: American Medical Association; American Nurses Association-American Nurses Foundation; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration; Food Safety and Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture[7]

Management

Non-pharmacological

Since acute HAV infection is usually a self-limiting illness, primary management is supportive care. The following advice can be offered to symptomatic patients:

- Rest when necessary;

- Avoid alcohol during the acute phase of the illness (while liver function tests [LFTs] are raised and they are feeling unwell) to prevent further damage to the liver;

- Take time off work/school until the infectious period has passed (minimum of seven days after the onset of symptoms);

- If the patient is experiencing pruritus, simple measures, such as wearing loose clothing, may help[15]

.

Pharmacological

Analgesics

If pain relief is required, paracetamol can be used at normal dosages unless there is evidence of moderate or severe liver impairment[15]

. In these instances, specialist advice should be sought with regards to dosing.

A weak opioid, such as codeine, can be given if the liver impairment is mild[15]

. However, codeine should be avoided if there is severe liver impairment owing to the risk of enhanced sedative effects and reduced drug clearance[15]

.

Antiemetics

If treatment of nausea is required, metoclopramide 10mg three times daily when required for a maximum duration of five days may be recommended if liver impairment is mild[15]

. Alternatively, ondansetron 4mg twice or three times daily when required for five days may be suitable.

Antipruritics

If treatment of pruritus is required, chlorphenamine can be taken at night at the standard dose of 4mg. The frequency of dosing can be increased to every four to six hours if the itch is severe[15]

. This should be avoided in patients with severe liver impairment owing to a risk of masking or worsening hepatic encephalopathy from its sedating effect[15]

.

Follow-up and referral

The frequency of LFT monitoring is dependent on both a patient’s symptoms and the trend in LFTs. Initially, LFTs should be checked three to five days after the diagnosis and weekly thereafter until consistent improvement is seen. Monitoring of LFTs can then be reduced to every two weeks, then to monthly once LFTs start to normalise (this may take up to 12 weeks from initial presentation)[15]

.

If LFTs are worsening, or if the patient develops any signs of acute liver failure (e.g. vomiting, jaundice), specialist advice should be sought without delay. The patient may be referred for specialist care in a tertiary liver facility that can undertake liver transplantation.

Prevention

Reducing the risk of transmission

Good hygiene measures can help minimise transmission of HAV. This includes the washing of hands after using the toilet, avoidance of handling food, avoidance of unprotected sexual intercourse and avoidance of the sharing of needles or drug paraphernalia[15]

.

For pregnant women with HAV, and for those who are actively trying to become pregnant during the period of infection, there is a greater risk of miscarriage and premature labour. Therefore, it is necessary for people in these groups to seek specialist obstetric advice. Breastfeeding is safe if good personal hygiene and careful hand washing are observed[15]

.

Immunisation

Mechanisms for the prevention of infection include vaccination against HAV and the use of immunoglobulin

[16]

. The HAV vaccine leads to the development of active immunity, but the response is not immediate. A monovalent HAV vaccine is available, or the HAV vaccine may be combined with typhoid or hepatitis B. The vaccines are all inactivated, do not contain live organisms and cannot cause the disease.

Monovalent vaccines

There are three monovalent vaccines that are currently available in the UK, prepared from different strains of the HAV and grown in human diploid cells[16]

. These are Havrix (GSK), VAQTA (Merck) and Avaxim (Sanofi); these vaccines can be used interchangeably[17],[18],[19],[20],[21]

.

Combined hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine

When protection against both hepatitis A and hepatitis B infections is required, patients can receive combined vaccines (Twinrix [GSK] and Ambirix [GSK]), which contain purified inactivated hepatitis A virus and purified recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen[22],[23],[24]

.

However, if rapid protection against HAV infection is required for adults following exposure or during outbreaks, a single dose of a monovalent vaccine is recommended. In children under 16 years of age, a single dose of Ambirix may also be used for rapid protection against hepatitis A[16]

.

Combined hepatitis A and typhoid vaccine

The combined vaccine containing purified inactivated hepatitis A virus and purified Vi capsular polysaccharide typhoid vaccine (ViATIM [Sanofi]) may be used where protection against hepatitis A and typhoid fever is required for people over the age of 16 years[25]

.

Pre-exposure immunisation

For effective long-term immunisation, two doses of a hepatitis A-containing vaccine at appropriate intervals are required for any individual at high risk of exposure to HAV or at risk of developing complications of the infection.

As per current guidance from the Department of Health and Social Care, there are several groups that are recommended to receive pre-exposure vaccination: people who are traveling or moving, patients with chronic liver disease, patients with haemophilia, MSM, injecting drug users and individuals at occupational risk.

Patients who are traveling or moving

People traveling or moving to an area of high or intermediate prevalence (anywhere outside northern or western Europe, Australia, North America and New Zealand) should recieve pre-exposure immunisation[16]

.

This vaccination is recommended for those over the age of one year, and should be given at least two weeks before departure, but can be given up until the day of departure. Antibodies may not be detectable for 12–15 days following the administration of the monovalent hepatitis A vaccine, but the vaccine may provide some protection before antibodies can be detected using current assays[16]

.

A single dose will provide protection for about one year, but for long-term protection over 25 years, a second dose should be given 6–12 months after the initial vaccine[16]

.

Patients with chronic liver disease

Although they may not be at an increased risk of acquiring HAV, infection can lead to a more serious illness in this patient cohort. This includes patients with:

- Alcoholic liver disease with cirrhosis;

- Chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection;

- Autoimmune hepatitis;

- Primary biliary cholangitis (previously primary biliary cirrhosis and recently updated to reflect that not all patients with this disease have cirrhosis);

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (a long-term, progressive, inflammatory disease of the liver and gallbladder)[16]

.

Patients with haemophilia

Vaccination is recommended as standard viral inactivation processes for blood products may not be effective against HAV. The vaccine should be given subcutaneously in this population[16]

.

Men who have sex with men

Public Health England (PHE) recommends that these patients are informed of the importance of hygeine as UK outbreaks in this group appear to be via the faecal–oral route[16]

.

Injecting drug users

Immunisation is recommended for this group and can be given at the same time as the hepatitis B vaccine, as separate or combined preparations[16]

.

Individuals at occupational risk

There is a wide range of people who work in occupations with a higher risk of infection:

- Microbiology laboratory workers or those working in clinical infectious disease units;

- Staff in large residential institutions;

- Sewage workers;

- People working with primates[16]

.

Individuals may also be considered for hepatitis A vaccination under certain conditions, for example staff in daycare facilities (particularly in situations where there is a well-defined community outbreak) and healthcare workers[16]

.

Post-exposure immunisation

Passive or active immunisation, or a combination of the two, is available for the management of the contacts of cases and for outbreak control[16]

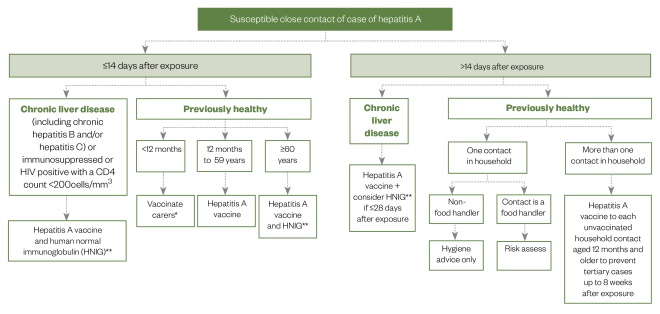

. An individual who is at high risk of being exposed to hepatitis A, owing to close contact with the index case during the infectious period, is known as a close contact. A risk assessment should be undertaken to identify close contacts, with consideration given to contacts who have shared food and toilet facilities with the index case, equivalent to a household-type exposure[26]

. There should be a low threshold for considering someone a close contact.

The national standard questionnaire for hepatitis A risk assessment should be completed by the clinical team looking after the index case. This can subsequently be used to seek the latest advice regarding the use of vaccine and human normal immunoglobulin (HNIG) from the local health protection team at PHE for close contacts of the index case.

Administration of the vaccine is effective in preventing infection in contacts of cases, provided it is given soon after the onset of symptoms in the index case (ideally within 14 days)[27],[28]

. The monovalent hepatitis A vaccine is the ideal choice for the outbreak setting[26]

. Those immunised should be informed that they should receive a second dose of vaccine 6–12 months after the first dose to ensure long-term protection, although this second dose is not essential for outbreak control[26]

.

HNIG is used primarily for prophylaxis for contacts of cases of acute HAV infection as it can provide immediate, passive protection, despite antibody levels being lower than those eventually produced by hepatitis A vaccine[16]

. HNIG can protect against HAV infection if administered within 14 days of exposure and may still modify the disease course if given after that time[27]

. Protection after using HNIG lasts for four to six months. The HNIG licensed for use for prophylaxis against HAV should have a hepatitis A antibody level of at least 100IU/mL. PHE regularly updates guidance on the specific dose and brand of HNIG to use, depending on HNIG brand-specific availability. Current guidance (updated in June 2019) is based on the use of Subgam (Bio Products Laboratory) HNIG[29]

.

When both rapid and prolonged protection is required, vaccination against hepatitis A and HNIG can be given at the same time, but should be administered at different sites of the body[26]

.

Figure 2 depicts a suggested algorithm for the management of close contacts of patients infected with hepatitis A.

Figure 2: Management options for close contacts of patients infected with hepatitis A

* if unfeasible those aged ≥2 months should be immunised (unlicensed)

** if feasible testing for anti-HAV IgG should be done prior to administration of HNIG

Source: Public Health England[26]

Role of the pharmacist

Hepatitis A is a vaccine-preventable disease, yet it remains a common cause of hepatitis globally. The presenting features of acute infection with HAV tend to be clinically indistinguishable from that of other viral hepatitis infections. Thus, a comprehensive history should be taken to identify risk factors for hepatitis A. Acute infection can be confirmed by serological testing for HAV IgM and HAV RNA. The management of acute hepatitis A is primarily supportive, and complete recovery from the illness is the most usual outcome.

Community pharmacists should provide advice on both non-pharmacological management and pharmacological treatment of symptoms described above. Pharmacists should also advise patients to seek medical attention if symptoms are worsening if they describe any symptoms indicating significant liver impairment (see Box 2).

It is essential that hospital pharmacists ensure appropriate medicines and doses are used for patients with significant liver impairment, and counselling is given on how to use medicines for symptom control as well as their potential side effects.

Specialist pharmacists in hepatology who run clinics and see patient with liver disease should be aware of the risk factors of developing hepatitis A and how to diagnose, manage and treat these patients, if this is within their scope of practice.

Box 2: Case study: a patient develops severe symptoms indicative of hepatitis A infection after a trip abroad

A 32-year-old female* self refers to her local A&E department with right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain, vomiting and jaundice.

Medical history

She has asthma and uses a salbutamol inhaler on an as-required basis. She has no known drug allergies. She does not smoke and has not taken any alcohol.

Observations/examination

The patient explains that she had returned from Ethiopia one week ago where she had attended a wedding. She had stayed with close relatives in the local area for 16 days. She adds that she has felt nauseous for one-week, but has had recurrent vomiting and abdominal pain for the past two days and recently noticed that her skin had developed jaundice — most noticeable in her eyes (scleral icterus).

The patient reported pale stools, but no diarrhoea. She had also noticed dark urine. The patient has been having fevers at night, but has no sweats or cold sensations (i.e. rigors). However, she has experienced generalised body aches, particularly in the shoulder joints and mid-thoracic spine.

After questioning, it was discovered that she did not have a headache, neck stiffness, pruritus or a skin rash. The patient says that she had not experienced any confusion.

Investigations

- Temperature: 36.6ºC;

- Heart rate: 107 beats per minute;

- Blood pressure: 120/65mm/Hg;

- Respiratory rate: 18 breaths per minute;

- Oxygen saturation: 99% on room air;

- Chest: clear to auscultation;

- Heart sounds: normal;

- Abdomen: soft, mild tenderness in the epigastric area, and right upper quadrant. Bowel sounds normal;

- Blood cultures: no growth;

- Hepatitis B, C and E screen: negative;

- Malaria screen: negative;

- Stool cultures: no evidence of infection or parasite;

- HIV screen: negative;

- Non-invasive metabolic and autoimmune liver screen: negative;

- Liver ultrasound: normal liver, spleen size normal, no free fluid;

- Pregnancy test: negative;

- Hepatitis A virus (HAV) IgM positive, HAV IgG negative and HAV RNA detectable.

Diagnosis

The patient is diagnosed with HAV because they meet the clinical case definition, are IgM positive and has been to a region where HAV is more prevalent. As the patient is in hospital, she would be diagnosed by the medical team with microbiology and hepatology input. Follow up would be with the hepatology team.

Management

- Intravenous fluids;

- Anti-emetics: metoclopramide 10mg three times daily as required;

- Pain relief: paracetamol 1000mg twice daily and codeine 30mg four times daily as required.

Public Health England is informed via email and close contacts to her are vaccinated as per guidance.

Discharge medicines

The patient is discharged three days after presentation with the following medicines:

- Paracetamol tablets: 1000g twice daily as required;

- Codeine phosphate tablet: 30mg orally, every six hours as required;

- Metoclopramide: 10mg three times daily as required.

The patient is advised to attend A&E should she feel unwell again.

Follow-up blood tests showed complete resolution of infection with negative HAV RNA in serum and stools after 12 weeks, associated with normalisation of transaminases, as shown in the Table, and no lasting symptoms.

| Table: Blood parameters at presentation and over a 12-week follow-up period | ||||

| Test (reference range) | Day | |||

| Day 0 (at presentation) | Day 2 | Day 28 | Day 84 | |

| AST (10–50IU/L) | 3,565 | 1,546 | 34 | 30 |

| ALT (5–55IU/L) | 4,002 | 1,793 | 52 | 29 |

| GGT (1–55IU/L) | 142 | 95 | 26 | 25 |

| ALP (30–130IU/L) | 176 | 138 | 65 | 50 |

| Albumin (35–50g/L) | 39 | 38 | 39 | 39 |

| Bilirubin (3–20micromol/L) | 137 | 102 | 25 | 11 |

| INR (0.9–1.2) | 1.26 | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.09 |

| Platelets (150–450 x109/L) | 169 | 200 | 439 | 405 |

| Creatinine (45–120micromol/L) | 56 | 54 | 55 | 56 |

| Urea (3.3–6.7mmol/L) | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| HAV RNA (serum) | Positive | – | Positive | Negative |

| HAV RNA (stool) | Positive | – | Positive | Negative |

| HAV IgM | Positive | – | Positive | Positive |

| HAV IgG | Negative | – | Positive | Positive |

| ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate transaminase; GGT: gamma-glutamyltransferase; HAV: hepatis A virus; INR: international normalized ratio; IgG: immunoglobulin G; IgM: immunoglobulin M | ||||

*Case study is fictional

References

[1] World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report, 2017. 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/ (accessed October 2019)

[2] World Health Organization. Hepatitis A. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-a (accessed October 2019)

[3] Sattar SA, Jason T, Bidawid S & Farber J. Foodborne spread of hepatitis A: recent studies on virus survival, transfer and inactivation. Can J Infect Dis 2000;11(3):159–163. doi: 10.1155/2000/805156

[4] Public Health England. Laboratory reports of hepatitis A infections in England and Wales, 2017: health protection report; volume 12 number 27. 2018. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/730084/hpr2718_hav-nnl.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[5] Beebeejaun K, Degala S, Balogun K et al. Outbreak of hepatitis A associated with men who have sex with men (MSM), England, July 2016 to January 2017. Euro Surveill 2017;22(5). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.5.30454

[6] Hawker J, Begg N, Blair Iet al. Communicable Disease Control Handbook. 2nd edn. New Jersey: Wiley; 2005

[7] American Medical Association; American Nurses Association-American Nurses Foundation; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration; Food Safety and Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture. Diagnosis and management of foodborne illnesses: a primer for physicians and other health care professionals. MMWR Recomm Rep 2004;53(RR-4):1–33. PMID: 15123984

[8] Glikson M, Galun E, Oren Ret al. Relapsing hepatitis A. Review of 14 cases and literature survey. Medicine (Baltimore). 1992 71(1):14–23. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199201000-00002

[9] Schiff ER. Atypical clinical manifestations of hepatitis A. Vaccine 1992;10(S1):S18–S20. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(92)90534-Q

[10] Gordon SC, Reddy KR, Schiff L & Schiff ER. Prolonged intrahepatic cholestasis secondary to acute hepatitis A. Ann Intern Med 1984;101(5):635–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-5-635

[11] Rahaman SM, Chira P & Koff RS. Idiopathic autoimmune chronic hepatitis triggered by hepatitis A. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89(1):106–108. PMID: 8273775

[12] Vento S, Garofano T, Di Perri G et al. Identification of hepatitis A virus as a trigger for autoimmune chronic hepatitis type 1 in susceptible individuals. Lancet 1991;337(8751):1183–1187. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92858-Y

[13] Shenoy R, Nair S & Kamath N. Thrombocytopenia in hepatitis A — an atypical presentation. J Trop Pediatr 2004;50(4):241. doi: 10.1093/tropej/50.4.241

[14] Ilan Y, Hillman M, Oren R et al. Vasculitis and cryoglobulinemia associated with persisting cholestatic hepatitis A virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85(5):586–587. PMID: 2337062

[15] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Hepatitis A. 2016. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/hepatitis-a (accessed October 2019)

[16] Public Health England. Immunisation against infectious disease; hepatitis A: chapter 17. 2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hepatitis-a-the-green-book-chapter-17 (accessed October 2019)

[17] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: Havrix monodose vaccine. 2016. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1158/smpc (accessed October 2019)

[18] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: Havrix Junior monodose vaccine. 2016. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1157/smpc (accessed October 2019)

[19] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: VAQTA adult. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1396 (accessed October 2019)

[20] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: VAQTA paediatric. 2017. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1397 (accessed October 2019)

[21] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: AVAXIM suspension for injection in a pre-filled syringe. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1394 (accessed October 2019)

[22] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: Twinrix adult vaccine. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1163 (accessed October 2019)

[23] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: Twinrix paediatric vaccine. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1164 (accessed October 2019)

[24] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: Ambirix suspension for injection in pre-filled syringe. 2016. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6172 (accessed October 2019)

[25] eMC. Summary of product characteristics: ViATIM suspension and solution for suspension for injection in pre-filled syringe. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1534 (accessed October 2019)

[26] Public Health England. Public health control and management of Hepatitis A. 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/727411/Public_health_control_and_management_of_hepatitis_A_2017.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[27] Sagliocca L, Amoroso P, Stroffolini T et al. Efficacy of hepatitis A vaccine in prevention of secondary hepatitis A infection: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353(9159):1136–1139. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08139-2

[28] Winokur PL & Stapleton JT. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis for hepatitis A. Clin Infect Dis 1992;14(2):580–586. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.2.580

[29] Public Health England. Human normal immunoglobulin (HNIG) for hepatitis A post-exposure. 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/810199/Immunoglobulin_handbook_hepatitis_A.pdf (accessed October 2019)