Alamy Stock Photo

In a time when the NHS is under tremendous budgetary pressure, decisions about healthcare, including which medicines and treatments are funded, can often lead to polarised opinions.

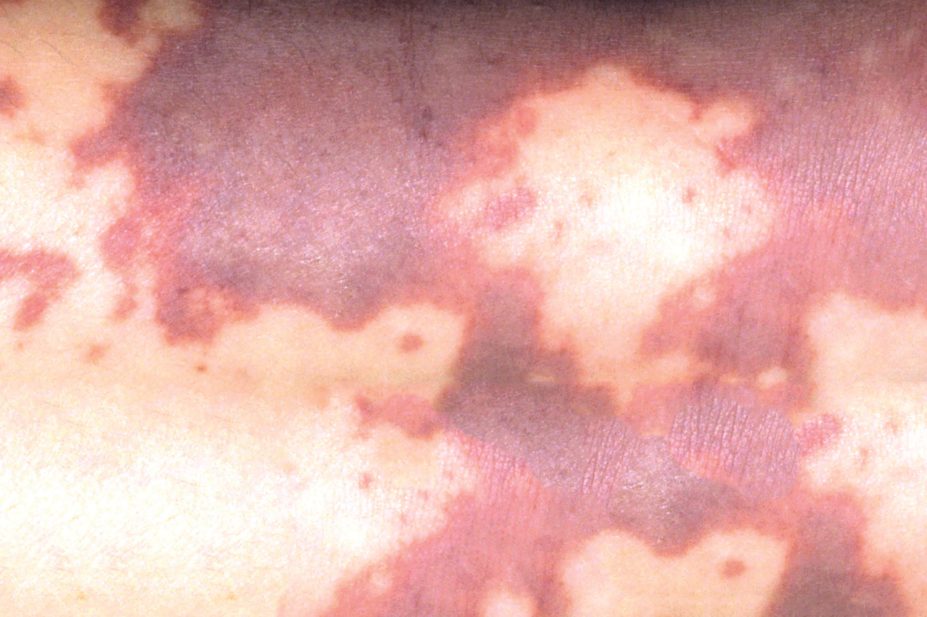

This is certainly the case with the debate surrounding the roll-out of meningitis B vaccine Bexsero by the NHS to babies aged between two and five months old born after 1 July 2015. Parents from Maidstone in Kent recently released photos of their two-year-old girl who died from the disease. One photograph showed the child smiling, while the other showed her bed-bound in hospital a few days later, covered in a non-blanching rash, distinctive in those infected with meningitis. The photos were widely shared on social media with a link to an online petition calling for the vaccine to be made available on the NHS to all children aged up to 11 years. It has since garnered more than 816,000 signatures – the most signed online petition in parliamentary history. On 2 March 2016, the government rejected the petition, but the issue is still scheduled to be debated in the House of Commons.

It is estimated that around 3,200 people develop bacterial meningitis and associated septicaemia in the UK each year, and meningitis B is the most common cause of bacterial meningitis (although cases have been declining steadily since 2000). Those at highest risk of contracting the infection are children aged under one year old.

Those children born before 1 July 2015 can receive the vaccination through private clinics, which costs up to around £200 (older children require two doses, so the cost goes up). However, clinics offering the vaccine outside the NHS vaccination programme are running low on stock. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the pharmaceutical company that makes Bexsero, after acquiring it from Novartis in a complicated asset sway in early 2014, confirmed it is unable to meet the surge in demand for the vaccine and will not be able to increase stock until the summer.

The UK is the first country in the world to offer Bexsero free under an immunisation programme after recommendations in 2014 from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) that the vaccine should be added to the childhood immunisation schedule. However, the road to this recommendation was riddled with controversy. There had already been a year-long pricing stand-off between the Department of Health and Novartis, and the decision to include the vaccine in the schedule only came after a reversal of a JCVI decision made a month prior. The committee did a U-turn on the decision following a substantial review of the cost-effectiveness assumptions and citing new evidence. It is not known how the JCVI adjusted the quality-adjusted life year gained resulting from vaccination with Bexsero (

The Pharmaceutical Journal 2014;293:425).

The UK government is right not to alter its policy on this vaccination on the basis of the petition, especially when data support the rationale for targeting those at highest risk of infection. It is worth noting that the public do have the power to influence decision-making on health policies in some cases, such as when the government set up the Cancer Drugs Fund in response to outcry over decisions not to fund certain cancer treatments. It is important that decisions on how vaccines are funded by the NHS are based on evidence and economic viability. But in this case a line has been drawn, and probably in the right place.