Key points:

- Providing medication optimisation support to care homes led to both improved outcomes and the safer use of medicines for care home residents.

- The Wigan Borough model supports care home staff as well as prescribers; focusing on improving processes within the care home, as well as individual reviews for residents. This approach has improved medicines optimisation over and above medicines review, allowing a more holistic approach.

- Medication reviews led to reduced inappropriate polypharmacy and pill burden, and improvements in a number of key quality outcomes including reduced use of hypnotics and reduced use of antipsychotics used for challenging behaviour associated with dementia.

- The support provided to care home staff to improve the safe use of medicines has supported both the local authority and Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspection process and has contributed to an improvement in CQC ratings for the homes supported.

- Wigan Borough CCG has demonstrated financial savings on the prescribing budget of £710,000 over a 2.5-year period, with a 2.7 return on investment.

Introduction

Around 426,000 people in the UK are living in residential (including nursing) care homes; 405,000 of these people are aged over 65 years[1]

. In this article, the term ‘care home’ covers the provision of 24-hour accommodation together with either non-nursing care (residential home) or nursing care (nursing home).

Wigan, a borough of Greater Manchester, England, has a population of 322,000 people. Around 51,000 people living in Wigan are aged 65 years or over, around 3.8% of whom live in a care home[2]

. There are 53 care homes (32 residential and 21 nursing) in Wigan Borough, providing a total of 2,223 beds.

The care home population is commonly associated with multimorbidity, defined as the presence of two or more chronic medical conditions. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), England’s health technology assessment body, estimates that 66% of people aged 65 years or over have multimorbidity and 47% have three or more conditions[3]

. Dementia, stroke, advanced cardio-respiratory disease, cancer and arthritis are the most common conditions associated with older care home residents[4]

.

The King’s Fund, an independent charity working to improve health and care in England, estimates that around 97% of care home residents are prescribed medication[5]

. Evidence suggests that, as a population, care home residents would potentially gain most benefit from medication reviews; research suggests that inappropriate prescribing may occur in 50–90% of older people living in care homes in the UK[6]

.

A 2016 report from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), the professional leadership body for pharmacists and pharmacy in Great Britain, states that each additional medicine prescribed for a patient is associated with an increased risk of errors, such as prescribing, monitoring, dispensing and administration errors and adverse drug reactions[7]

. The prevalence and causes of prescribing errors in general practice (PRACtICe) study found that in general practice in the UK there was a 16.0% increased risk of error for each additional unique medication item patients received over the 12-month study period[8]

. The Care Home Use of Medicines Study (CHUMs) found that care home residents are prescribed an average of 7.2 medicines per day and found errors in 8.4% of observed medication administration events[9]

.

The NICE guideline on managing medicines in care homes[6]

and associated quality standards[10]

advise that care home residents should have a multidisciplinary medication review at least annually. The RPS recommends that medication reviews should be pharmacist-led[7]

. As well as improving safety and rationalising medication regimes, research has shown that pharmacist-led medication reviews can lead to a reduction in the number of falls (secondary to reduction in use of medicines known to cause falls), and the use of psychotropic medicines[11],[12]

.

Falls

Falls are the most common cause of mortality resulting from injury and are a major cause of disability in older people aged over 75 years in the UK. Living in a care home is associated with an increased risk of falls[13]

.

Almost any medicine that acts on the brain or the circulation (e.g. one that reduces blood pressure or slows heart rate) can cause a fall. Stopping cardiovascular medicines reduces syncope and falls by 50%[14]

. Psychotropic medicines cause sedation, slow reaction times, can impair balance and double the risk of falling. There is good evidence that stopping these drugs reduces falls[15]

.

Hypnotics

Risks associated with the long-term use of hypnotics (including benzodiazepine and Z-drugs) have been the subject of a number of safety alerts. The risks include falls, accidents, cognitive impairment, dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and an increased risk of dementia[16]

. Studies have suggested a link with Alzheimer’s disease[17]

, increased risk of fractures[18]

and increased risk of death from any cause in people taking these medications in the long term[19]

.

NICE recommends that people prescribed hypnotics are reviewed with the aim of reducing hypnotic prescribing. Benzodiazepine withdrawal is particularly important in older people as they are more prone to their adverse effects[20]

.

Low-dose antipsychotics for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

The risks and limited benefits of using first-generation (typical) and second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic drugs to manage challenging behaviours associated with dementia (BPSD) are well recognised[16]

. People living with dementia are at a higher risk of strokes from antipsychotic medication, which is associated with increased mortality[21]

, but antipsychotic drugs are of limited benefit for the treatment of BPSD[12]

. A 2009 report from the Department of Health, the ministerial department responsible for government policy on health and social care, found that the level of use of antipsychotics for people living with with dementia presented a significant issue in terms of quality of care, clinical effectiveness and patient safety and experience, and consequently issued a national directive to reduce their use[12]

.

Proton pump inhibitors

There are growing concerns about long-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), with observational studies indicating associations with Clostridium difficile infection and increased risk of bone fractures[22]

. Biological mechanisms suggest potential associations with acute interstitial nephritis, hypomagnesaemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, rebound acid hypersecretion syndrome and increased mortality in older people[22]

.

Osteoporosis prevention

Osteoporosis increases bone fragility and increases an individual’s susceptibility to fracture. Worldwide, osteoporosis is responsible for around 9 million fractures each year[23]

. Several therapies are available for the prevention of fragility fractures in people who are at risk, and for fracture prevention in people who have already experienced one, or more, fragility fractures[23]

. There is some debate over the ideal duration of therapy[24]

, particularly with the emergence of links with the rare but serious complications of osteonecrosis of the jaw and external auditory canal, atypical femoral fracture and atrial fibrillation (AF)[25]

.

NICE recently published quality standards for osteoporosis that recommend adults at risk of fragility fracture be offered drug treatment to reduce their risk, and that those on long-term bisphosphonate therapy be reviewed for continuing treatment need[26]

.

Stroke prevention

AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia. The aim of treatment is to prevent complications (particularly stroke), and to alleviate symptoms[27]

. Anticoagulants are used to reduce the risk of stroke; however, all anticoagulants increase the risk of major bleeds[28]

. Residents and their carers should be supported, through shared decision making, to choose whether to take an anticoagulant based on their personal risks and preferences.

Inhaler technique

Inhaled medications are the standard first-line treatment for both asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, using inhalers can be difficult, leading to suboptimal use and effect[29]

. Studies indicate that around 90% of people using pressurised metered dose inhalers and around 54% of people using dry powder inhalers may not be using their inhalers correctly[30]

. Inadequate inhaler technique lowers drug deposition within the lungs, and can lead to poor disease control, reduced quality of life, increased emergency hospital admissions and higher treatment costs[30]

. NICE quality standards for both asthma[31]

and COPD[32]

include recommendations for healthcare professionals to regularly assess the patient’s inhaler technique.

Polypharmacy and pill burden

Polypharmacy is defined as the concurrent use of multiple medicines by an individual[33]

.

Where the use of multiple medicines results in the risks outweighing the benefits, the term ‘inappropriate polypharmacy’ is used[5]

. Polypharmacy in people with multimorbidity is often caused by the introduction of multiple medicines intended to prevent future morbidity and mortality associated with each individual health condition. However, the absolute benefit gained from each additional medicine is likely to reduce when people take multiple preventative medicines, while the risk of harm increases[16]

. More medicines taken in combination create a higher risk of potentially hazardous interactions and a prescribing cascade can occur as additional medicines are prescribed to treat the side effects of other medicines.

Pill burden (the number of individual doses of medicine a person takes regularly each day), which reflects the overall demand of medicines taking, can become unacceptable. Keeping the medication regimen as simple as possible reduces the pill burden required to provide effective treatment[5]

. This reduces the impact of medicine-taking on the individual, and can help improve medicines adherence[34]

.

Aim

The medicines management group of the Wigan Borough Clinical Commissioning Group (WBCCG) developed an approach to improving medicines optimisation for care home residents. This article describes the WBCCG model of care and the outcomes achieved from the start of the service in August 2014 to the end of the 2016–2017 financial year. This is a service evaluation, so ethical approval was not required.

Method

Funding and staffing

In April 2014, WBCCG secured funding from the Better Care Fund, a programme spanning both the NHS and local government that seeks to join up health and care services[35]

, to employ two whole-time equivalent (WTE; defined as the hours worked as a proportion of the contracted hours normally worked by a full-time employee in the post) pharmacists for one year (August 2014–July 2015) to support GP practices in undertaking medication reviews for care home residents. Before this, no service provided this specific type of support locally. WBCCG’s initial findings identified that care home staff required support for the safe use and handling of medicines.

In May 2015, funding was secured to recruit two WTE care home technicians to work with care home staff to review processes and procedures within care homes (August 2015–July 2016). At this time, funding was also secured to retain the existing two pharmacists for a further 11 months (August 2015–July 2016).

As a result of the service achieving the pre-specified outcomes in May 2016, WBCCG allocated recurrent funding to secure the four permanent posts for continuing service delivery.

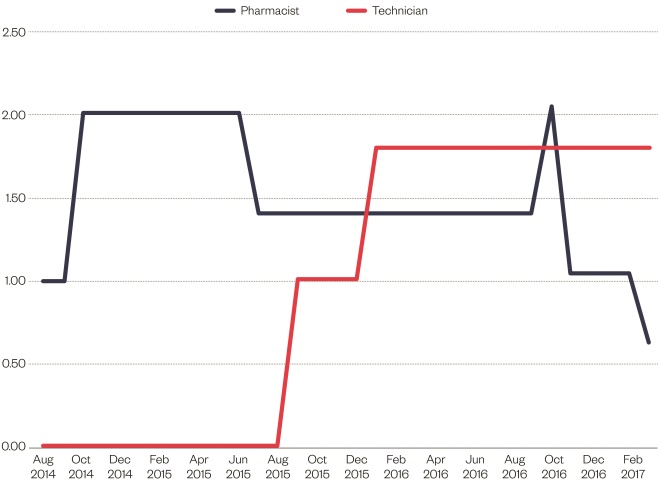

Pharmacist staffing levels varied over the reporting period; they were impacted because the original posts were temporary and there were difficulties encountered in retaining band-7 pharmacists. Pharmacy technician levels remained constant since staff recruitment. On average, the pharmacist staffing level was 1.26 WTE over the reported period (August 2014–March 2017), with 1.8 WTE pharmacy technicians (see Figure 1: Pharmacist and technician whole-time equivalent staffing levels [August 2014–February 2017]).

Figure 1: Pharmacist and technician whole-time equivalent staffing levels (August 2014–February 2017)

Pharmacist staffing levels varied over the reporting period, with the average staffing level being 1.26 whole-time equivalent (WTE) over the reported period. Technician staffing was more stable at 1.80 WTE

Initiating support

Support was initially focused on six care homes within the WBCCG that had received poorer ratings from the Care Quality Commission (CQC), the independent regulator of all health and social care services in England, or had been identified by the Local Authority Oversight team, which carries out care home monitoring locally.

The Local Authority Oversight team monitored CQC ratings and contacted GP practices and care homes directly to offer and arrange support. Relationships were built with the local authority, which was able to contact the care home team as soon as it became aware of any medicines-related issues through monitoring activities or safeguarding reports. This ensured the team prioritised support to those care homes requiring more urgent intervention and support.

The role of the care home team was discussed with all GP practices during the 2015 Medicines Optimisation Peer Review Programme[36]

and at the local authority’s care home forum to raise awareness of the support available.

The team focused work on a care home basis, rather than by GP practice. Residents of a single care home may be registered with several different GP practices; for example, in a single 40-bed care home, residents were registered with a total of 10 different GP practices. By focusing work on the care homes, all appropriate residents were reviewed and support on medicines-related systems and processes was given, addressing multiple medicines-related problems at once (including side effects, monitoring, synchronisation, ordering process, when required [PRN] dosing processes and missed doses).

Following an assessment or referral that identified a home may benefit from the team’s support, care home managers (or area managers) were contacted directly by the care home team. The medicines-related problems identified by monitoring processes and the care home were discussed at the initial meeting between the pharmacist or pharmacy technician and the care home manager, along with any concerns. The team discussed and agreed the most appropriate way of working with the care home staff and arranged to carry out the NICE baseline assessment audit if required[37]

. The pharmacy technician assigned to the home determined the amount of support provided based on the outcomes of any audits completed and the agreed requirements of the care home, and ranged from single to weekly visits (see Figure 2: ‘Care home support’). The team obtained a list of GP practices with whom residents were registered, and identified associated community pharmacies dispensing medication for the care home.

The pharmacists contacted the relevant GP practices and met with practice managers to discuss the care home team service; they arranged access to the GP clinical records and established the best way of working with the practice.

Medication review

Medication review is defined by NICE as: “a structured, critical examination of a person’s medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the person about treatment, optimising the impact of medicines, minimising the number of medication‑related problems and reducing waste”[38]

.

Pharmacists within the care home team collaborated with the individual residents, the carers and GP to achieve this. They ensured that prescribed medicines: had a clear indication that met the person’s needs; the medicines used were evidence-based and cost effective; the correct dose and formulation was used to ensure maximum benefits and minimum side effects; all monitoring was undertaken to ensure the safe use of the medicine and that any unmet pharmaceutical needs were identified.

The pharmacists were not prescribers and, therefore, made recommendations regarding appropriate interventions or changes to the resident’s GP. Following GP review and feedback on the suggested amendments, the pharmacist ensured all agreed changes were implemented and noted in the resident’s clinical record. Multidisciplinary face-to-face discussions were the preferred method of communication between the GP practices and the care home team because it supported an informed discussion around the suggested interventions, enabling the pharmacist to provide additional detail and context if required. Discussions were carried out within the GP practice ensuring that the GP had access to the individual’s clinical and care records if needed. If the practice was unable to accommodate this approach, the GP reviewed a written list of recommendations, agreeing or rejecting each proposed intervention.

Following implementation of recommendations, the pharmacist or pharmacy technician communicated all changes to the care home ensuring the resident and care home staff understood the treatment plan, and that the care home’s paperwork was updated. They also provided relevant information to the community pharmacy supplying the care home with medicines.

Care home support

Pharmacy technicians used the NICE baseline assessment audit[37]

related to the NICE guideline ‘Managing medicines in care homes’ [SC1] to identify areas where the care home needed additional support. The technicians also discussed medicines issues with staff and managers, observed medicines administration rounds and obtained information from recent inspections or ongoing monitoring, such as those conducted by CQC or the Local Authority Oversight Team to identify areas for improvement.

The level of input and support offered was tailored to meet the needs of the care home, and the pharmacy technicians worked with care home staff to improve and support safe care of their residents by:

- Improving medicines safety (e.g. reviewing administration procedures, providing education and advice to enable staff to better manage residents’ medicines);

- Supporting staff to implement relevant guidance[6],[10],[39]

; - Reducing waste by reviewing ordering procedures and improving medicines handling (storage and disposal).

Data collection

The first medication reviews were completed in October 2014. Data collection for the project was complex, and it was only after the initial medication reviews were completed that the type of interventions were identified and classified. A recording system was developed and tested using a Microsoft Access database and the final data collection tool was defined. It was not practical to record the detail of every medication that residents were prescribed, nor every alteration made, as this would have required the use of a drug dictionary to enable comparison between individuals, which was not available to the team. It was decided to collect demographic data, data for the key quality outcome measures identified and financial savings.

The quality areas that were selected were mainly chosen from those identified in the ‘CCG Medicines Optimisation Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP)[40]

plan’ (see Box 1: Quality areas selected from the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention plan).

Box 1: Quality areas selected from the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention plan

- Reducing hypnotic prescribing;

- Reducing the use of low-dose antipsychotics in dementia;

- Reducing proton pump inhibitor use;

- Prevention of osteoporosis;

- Prevention of atrial fibrillation-related stroke;

- Reducing falls risk associated with medicines;

- Improving inhaler technique;

- Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy;

- Reducing pill-burden.

A separate reporting tool (a Microsoft Access database) was developed for the care home support provided. Support was grouped under general themes and although much of the pharmacy technician input was interlinked, for reporting purposes, interventions were defined as specific areas. For data collection, where systems were in place and generally being followed with only minor feedback, this was not recorded as providing support. For example, when fridge procedures were in place and staff could use the equipment, but occasional failure to record temperatures was noted, this would be documented as not needing support, although a reminder of the importance of recording fridge temperatures would be given. By contrast, a care home where a procedure was not in place, or temperatures were regularly not recorded, or staff were not using equipment correctly (failing to reset the thermometer following recordings) would result in a record of requiring support, with subsequent support and training being provided.

Financial savings

Savings were calculated following processes already in place within WBCCG for the medicines management team interventions when calculating medicines optimisation QIPP savings. This approach was in line with the methodology followed by other CCGs locally. Savings were calculated where prescribing changes were made. As the team implemented changes to prescribing systems, any related savings could be identified and calculated. When recording savings data, it was not planned to analyse savings or to compare these results between individuals. Savings were calculated per medicine changed and recorded as a total saving per resident reviewed.

Overall, savings were calculated as the difference in cost between the previous and the adjusted (or stopped) medication, and were calculated for a 12-month period indicating within which financial year savings would be achieved. For example, a £1,200 annual saving instigated in October 2015 would result in savings of £600 in 2015–2016 and £600 in 2016–2017. Savings for medications that were not used regularly were calculated based on usage over the previous six months.

In situations where review of ordering processes at a care home resulted in the avoidance or reduction in medicines returned for destruction (by carrying stock forward to the next monthly cycle), this was calculated as a one-off saving related to the products that were not destroyed, and these savings were not annualised. These savings were recorded and attributed to the care home where the saving was made rather than to individual residents.

Training

All staff joining the care home team required significant training to support them to work effectively. The pharmacists employed came from community and hospital pharmacy backgrounds, therefore they did not have experience of working with general practice or care homes, and had not carried out structured clinical medication reviews in this setting. They were trained and supported to develop effective working relationships with GP practices, gaining a working knowledge of GP prescribing systems and updated their clinical knowledge in relation to conducting medication reviews for frail older people, learned about care home systems and processes, and established a working practice with care home managers.

The technicians came from a community and hospital background and had not worked in the care home or general practice setting. They required support in using primary care systems, care-home monitoring, local authority procedures for improvement and the care home working environment. This was a new area of work for the medicines management team and there was little previous local experience on this type of primary care support.

Training on GP systems and processes and clinical training was provided by the existing medicines management team and relevant clinical training from external providers (e.g. Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education and the Primary Care Pharmacy Association). The team visited a GP practice with a contract to provide services to care home residents within a neighbouring CCG, which employed a pharmacist and technician, to learn from their experience. Shadowing was arranged with care home staff and managers to support understanding of care home systems. Training was provided by the Local Authority Market Oversight Team and a CQC inspector to support understanding of the monitoring processes in place. The technicians attended training provided locally to care home staff. The team also joined relevant forums, such as the RPS care home forum, to learn and share learning with others.

Results

Results from all resident medication reviews and care home support from August 2014–March 2017 are included. Results for 2014–2015 represent eight months of service provision and include the initiation phase of the project where there was a higher need for training and time required to build effective working relationships.

The care home team completed a total of 749 medication reviews during the evaluation period (1 August 2014–31 March 2017); demographic details are summarised in Table 1: ‘Demographic data of care home residents reviewed’.

Overall, 2,947 recommendations were made to prescribers (a mean of 4 per resident), of which 2,515 were accepted (84.5%). Data explaining why GPs chose not to implement recommendations were not collected during the evaluation period, but is something the team plans to record in the future.

| 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of residents reviewed | 93 | 277 | 379 |

| Male | 24 (26%) | 82 (30%) | 106 (28%) |

| Female | 69 (74%) | 195 (70%) | 273 (72%) |

| Aged <65 years | 6 (6%) | 15 (5%) | 20 (5%) |

| Aged 65–75 years | 12 (13%) | 32 (12%) | 42 (11%) |

| Aged 75–85 years | 33 (35%) | 89 (32%) | 105 (28%) |

| Aged >85 years | 39 (42%) | 134 (48%) | 210 (55%) |

The number of reviews completed each year increased, reflecting the increasing experience of the pharmacists and that the introduction of pharmacy technicians could enable pharmacists to focus on the clinical medication review process.

Table 2: ‘Quality outcomes’, contains data collected on the quality-prescribing areas selected for review at the start of the project.

| 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication reviews completed | 93 | 277 | 379 | 749 |

| Medicines associated with falls reduced | 45 | 100 | 151 | 296 |

| Prescribed hypnotic | 20 | 35 | 58 | 113 |

| Recommendation to reduce hypnotic | 19 | 32 | 51 | 102 |

| Hypnotic reduced | 16 | 25 | 33 | 74 |

| Dementia prescribed antipsychotic | 17 | 38 | 23 | 78 |

| Recommendation to reduce antipsychotic | 7 | 35 | 20 | 62 |

| Antipsychotic reduced | 5 | 27 | 11 | 43 |

| Prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) | 44 | 115 | 152 | 311 |

| Recommendation to reduce PPI | 37 | 78 | 105 | 220 |

| PPI reduced | 35 | 70 | 93 | 198 |

| Osteoporosis risk | 68 | 95 | 32 | 195 |

| Bone-sparing agent initiated | 6 | 74 | 27 | 107 |

| Atrial fibrillation, not anticoagulated | 11 | 8 | 19 | 38 |

| Recommendation to inititate anticoagulant | 7 | 5 | 13 | 25 |

| Anticoagulant initiated | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Prescribed inhalers | 13 | 25 | 27 | 65 |

| Inhaler technique assessed | 7 | 23 | 25 | 55 |

| Sub-optimal technique | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

Medicines associated with falls were either reduced or stopped for 296 residents (39.5%). Owing to the limitations of the data collected and the multifactorial nature of falls, it is not possible to quantify an associated reduction in falls risk.

In total, 113 residents (15.1%) taking hypnotic medication were reviewed and recommendations to either reduce or stop this medication were made for 102 of them. Reasons why a reduction was not recommended included appropriate short-term use, or residents being under the remit of mental health teams who were advising on management. Hypnotics were either reduced or stopped in 74 people (65.5% of all those on hypnotics and 72.5% of those on hypnotics where a recommendation was made).

Overall, 58.3% of the residents reviewed had a diagnosis of dementia, 78 of whom (17.8%) were prescribed an antipsychotic. Recommendations to reduce and potentially stop this medication were made for 62 of them. Reasons why no recommendation was made for some residents include them being under the care of a mental health team for their symptoms, or the antipsychotic being prescribed for a diagnosed mental health condition (e.g. schizophrenia). A gradual dose reduction was recommended with residents either stopping the medication or reducing this to the minimum effective dose. Medication was reduced or stopped in 43 people (55.1% of all residents with dementia prescribed a low dose antipsychotic, 69.3% of residents where a recommendation was made).

A PPI was prescribed in 311 (41.5%) of all people reviewed. A recommendation to review this medication with the aim to reduce doses and stop medication was made for 220 residents (70.7%). This recommendation was accepted for 198 residents (63.6% of all those prescribed a PPI and 90.0% of those where a recommendation was made).

Of those reviewed, 195 residents (26.0%) were identified as being at risk of osteoporosis or osteoporosis-related fracture, but had no bone-sparing agent prescribed. GPs initiated therapy on the pharmacist’s recommendation for 107 people (54.8% of at-risk residents). Reasons for not requesting initiation of therapy included contraindications, such as renal impairment and where bisphosphonates had previously been used for three to five years. Data on residents who had been taking long-term bisphosphonates who were reviewed for continued appropriateness of therapy were not recorded. Data on whether the bisphosphonate treatment was for primary or secondary prevention of osteoporosis-related fracture were also not recorded; therefore, potential cost savings of preventing fragility fracture could not be calculated.

In total, 96 of the residents reviewed had a diagnosis of AF, 38 (39.6%) of whom were not prescribed an anticoagulant. The pharmacists identified that it was appropriate to consider anticoagulant therapy for 25 (65.8%) of these residents, based on contraindications, exception reporting and bleeding risks. Anticoagulant therapy was initiated for six people (15.8% of all residents with AF and no anticoagulant and 24.0% of this group where a recommendation was made). The low uptake of this recommendation is thought to reflect the complex co-morbidity of this group, along with concerns regarding bleeding risks. The benefit obtained from anticoagulants in AF depends on the underlying risk of stroke (calculated using CHA2 DS2 -VASc). The residents’ stroke risk were not recorded and, therefore, it is not possible to identify specifically what impact has been achieved in terms of stroke reduction.

Overall, 65 of the residents reviewed were using inhalers (8.7%), and inhaler technique was assessed for 55 people (84.6%). In the vast majority of cases (n=48; 87.3%), inhaler technique was good, with only seven people identified as requiring support in this area. Counselling on appropriate technique was provided and, where necessary, inhalers were changed to different devices.

The medication review process focused on the safe use of medicines by ensuring that all relevant monitoring was up to date and, where necessary, referrals were made to other healthcare professionals. Monitoring was arranged for 349 people (46.6%); 43 residents (5.7%) were referred to other services. Data were not collected on the costs associated with monitoring or referrals.

One of the aims of the project was to reduce inappropriate polypharmacy, while ensuring residents were on the minimum effective dose, whether this related to dose or frequency. All medications were reviewed with a view to stopping them, reducing the daily dose, or reducing regular medication to PRN use (see Table 3: ‘Polypharmacy outcomes’).

| 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular medications prescribed for all residents pre-review | 759 | 2,749 | 3,372 |

| Mean number of regular medications taken pre-review | 8.2 | 9.9 | 8.9 |

| Regular medications prescribed for all residents post-review | 611 | 2,332 | 2,852 |

| Mean number of regular medications taken post-review | 6.6 | 8.4 | 7.5 |

| ‘When required’ (PRN) medications prescribed for all residents pre-review | 155 | 291 | 381 |

| Mean number of PRN medications taken pre-review | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| PRN medications prescribed for all residents post-review | 179 | 393 | 552 |

| Mean number of PRN medications taken post-review | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Residents where pill burden was reduced | 72 | 233 | 311 |

| Total number of medications stopped | 196 | 565 | 865 |

| Total number of dose reductions | 66 | 210 | 267 |

| Total number of dose increases | 12 | 17 | 13 |

| Total number of medications initiated | 87 | 205 | 384 |

The project achieved a reduction in inappropriate polypharmacy. The residents reviewed were taking 6,880 regular medications at the same dose and frequency every day (mean 9.2, range 1–32) prior to review. A reduction in prescribed regular items of 1,085 (15.8%) was achieved, reducing the mean to 7.7 (range 0–29).

The residents were taking 827 medications on an as-required basis (mean 1.1, range 0–16). Following reviews, the number of medicines increased to 1,124 (mean 1.5, range 0–8). This increase resulted from changing medicines that were prescribed regularly to when required use; this was generally associated with analgesics and laxatives, and was informed by discussions with the individual (or their carer), and administration patterns within the care homes.

Pill burden was reduced for 616 residents (82.2%). Owing to the data collection method used, it is not possible to identify the clinical areas in which pill burden has been reduced, which is a limitation of being unable to record all interventions at individual drug level.

Care home support

Support was offered to 31 care homes during the reported time period, with 29 homes (94.0%) accepting support.

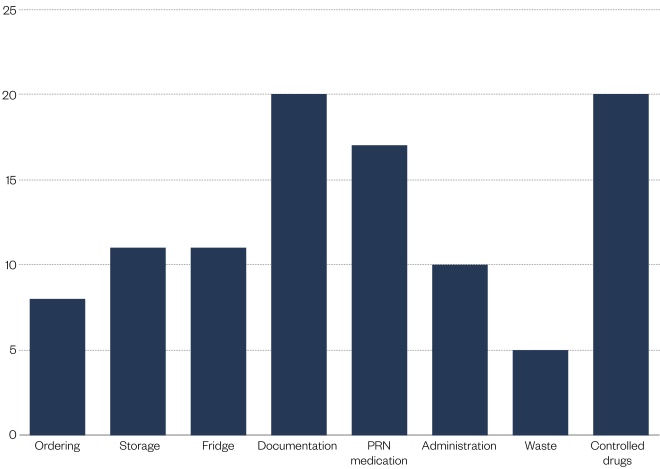

Figure 2: ‘Care home support’, details the support provided, which is categorised as:

- Ordering: not checking orders; lack of stock leading to missed doses; not following NICE guidance;

- Storage: safe storage of medicines, such as locked cupboards and rooms; security of trolleys; room-temperature monitoring; and annotation of reduced expiry dates. Excluded: controlled drugs and fridge issues;

- Fridge: appropriate monitoring of fridge temperatures and procedures where fridge temperatures go outside of range; storage of appropriate items in fridges;

- Documentation: written policies and procedures, such as medicines policy; information included on medication administration records (MAR charts), such as personal identification; use of resident photographs; recording of medication administration, such as missed doses and omission codes; documentation to support safe use of high-risk medication, such as anticoagulants. Excluded: PRN medications;

- PRN: any issues with PRN medication (e.g. use of PRN protocols, recording of administration), ensuring appropriate dose intervals for PRN medication;

- Administration: issues with administration procedures, such as observing time requirements regarding food, secondary dispensing and covert administration. Excluded: the documentation of administered doses;

- Waste: where large stockpiles of medication were found or homes return unused medication at the end of the month for destruction;

- Controlled drugs (CDs): any issues with CDs and their administration; safe and secure storage and recording (e.g. use of CD registers and appropriate dose intervals).

Figure 2: Care home support

Support was offered to 31 care homes during the reported time period, with 29 homes (94.0%) accepting support. Greater levels of support provided focused on documentation, PRN medication and controlled drugs.

Table 4 shows the dates when technician support to each care home commenced. Table 5 shows the CQC ratings achieved by the care homes supported. Under the current CQC inspection framework, care homes are awarded one of four ratings: ‘outstanding’, ‘good’, ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’[41]

. This can be subdivided into five domains with medicines management forming one component of the ‘safe’ domain[42]

. Where the technician support was provided before CQC ratings were published, there was either prior knowledge of the outcome of the inspection or the care home had been highlighted by the local authority monitoring processes. Where homes have been rated ‘good’ by CQC but subsequent support was provided, this was a result of local authority monitoring or safeguarding reports.

| Care home | Date | Care home | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13/10/2015 | 16 | 04/04/2016 |

| 2 | 01/11/2015 | 17 | 04/05/2016 |

| 3 | 07/01/2016 | 18 | 05/05/2016 |

| 4 | 15/01/2016 | 19 | 08/05/2016 |

| 5 | 20/01/2016 | 20 | 11/05/2016 |

| 6 | 28/01/2016 | 21 | 24/05/2016 |

| 7 | 29/01/2016 | 22 | 25/05/2016 |

| 8 | 26/01/2016 | 23 | 22/06/2016 |

| 9 | 01/02/2016 | 24 | 30/08/2016 |

| 10 | 21/03/2016 | 25 | 26/09/2016 |

| 11 | 08/02/2016 | 26 | 30/11/2016 |

| 12 | 18/02/2016 | 27 | 24/01/2017 |

| 13 | 07/03/2016 | 28 | 25/01/2017 |

| 14 | 07/03/2016 | 29 | 01/03/2017 |

| 15 | 07/03/2016 | — | — |

| Care home | Date | Overall rating | Safe rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18/05/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 03/08/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate | |

| 03/02/2017 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 2 | 11/05/2015 | Requires improvement | Inadequate |

| 27/01/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate | |

| 02/07/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 19/08/2017 | Good | Good | |

| 3 | 10/08/2016 | Good | Good |

| 4 | 08/02/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate |

| 24/08/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate | |

| 27/01/2017 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 5 | 22/09/2016 | Good | Good |

| 6 | 07/10/2015 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 21/02/2017 | Good | Good | |

| 7 | 28/07/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate |

| 24/01/2017 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 8 | 14/04/2017 | Good | Good |

| 9 | 24/06/2016 | Good | Good |

| 10 | 15/06/2016 | Requires improvement | Inadequate |

| 06/07/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 27/06/2017 | Good | Good | |

| 11 | 30/06/2017 | Good | Good |

| 12 | 19/07/2016 | Good | Good |

| 13 | 24/08/2016 | Good | Good |

| 14 | 07/04/2016 | Requires improvement | Inadequate |

| 17/11/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 01/04/2017 | Requires improvement | Good | |

| 15 | 14/10/2016 | Good | Good |

| 16 | 22/02/2016 | Good | Good |

| 17 | 05/10/2015 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 13/05/2017 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 26/09/2017 | Good | Good | |

| 18 | 02/04/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 19 | 28/10/2016 | Good | Good |

| 20 | 21/06/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate |

| 26/01/2017 | Good | Good | |

| 21 | 28/08/2015 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 16/07/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate | |

| 13/12/2016 | Good | Good | |

| 22 | 28/05/2016 | Inadequate | Inadequate |

| 23/12/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 17/05/2017 | Requires improvement | Good | |

| 23 | 22/05/2015 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 01/02/2016 | Good | Requires improvement | |

| 24 | 13/05/2015 | Good | Good |

| 15/08/2017 | Inadequate | Inadequate | |

| 25 | 11/06/2015 | Good | Requires improvement |

| 26 | 02/03/2015 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 26/08/2015 | Requires improvement | Not assessed (focused visit) | |

| 28/01/2017 | Good | Good | |

| 27 | 21/09/2015 | Requires improvement | Inadequate |

| 28/04/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement | |

| 10/06/2017 | Good | Good | |

| 28 | 25/08/2016 | Good | Good |

| 29 | 10/09/2016 | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

The support from the care home technicians contributed to rating improvements; particularly where the CQC rating was followed by a local authority service improvement plan (SIP) to address concerns identified. Where medicines-related SIPs were implemented, the care home team was responsible for developing, reviewing and updating the SIP, and advising the local authority when improvements were sustained, allowing the sign-off of the medicines-related section of the SIP.

Financial savings

The full range of work carried out from August 2014–March 2017 achieved savings of £710,000 on prescribing costs.

Based on actual staffing levels and midpoint salary, plus on-costs from agenda for change 2016–2017 (band 7=£45,389 and band 5=£30,053), staffing costs for the project were £259,193. Therefore, the return on investment for this project is 2.7, based on the prescribing savings achieved. This means that for every £1 invested, savings of £2.70 were achieved, although costs from other sources (e.g. monitoring and referral) are not included in this calculation

There may also have been secondary savings resulting from the prevention of adverse events, such as falls, fractures and stroke. However, from the data available, it is not possible to calculate these savings.

Discussion

A Cochrane review[43]

and NICE[6]

have concluded that although there is limited evidence for medication review and pharmacist-led interventions to resolve medicine-related problems, these interventions are promising and represent good practice.

Medication review

This service evaluation shows that pharmacist-led multidisciplinary medicine reviews for care home residents can lead to a reduction in inappropriate polypharmacy, reduced pill burden, support for the safe use of medicines, reduced cerebrovascular and cardiovascular risk, and reduced falls and fracture risk. There are additional clinical areas where the team could collect data to evidence improved care, such as in reducing anticholinergic burden (the cumulative effect of using multiple medications with anticholinergic properties together[44]

), that is increasingly recognised as a problem for older people[45]

. The team is currently developing the data collection method for this.

Other projects, such as the SHINE study[46]

, have used pharmacist independent prescribers in similar roles. No problems were encountered within this service because the pharmacists were not prescribers, although this is a potential future development.

When the technicians joined the team there was an increase in the number of medication reviews completed. The technicians were able to support this process by collating information from MAR charts, liaising with care home staff, assessing inhaler technique, ensuring care home records were updated and liaising with community pharmacies.

The feedback from GPs has been positive and the support welcomed. In particular, GPs have suggested that some of the success in reducing both hypnotics and low-dose antipsychotics was a result of the additional ongoing support the pharmacist provided when implementing the reduction regime. This support ensured staff, including night staff, were aware of: the treatment plan; the need to try any dose reduction for at least two weeks, to ascertain the true impact of any effects; what action to take if problems were experienced and addressed specific care home staff concerns

Arranging the timely discussion of medication reviews between the pharmacist and GP, as well as ensuring the resident (or their carer) was actively involved in the process, was a challenge for the team. A ward-round approach is being developed that will facilitate a person-centred approach for both the pharmacist and GP.

Care home support

The pharmacy technician role was developed to meet a need identified in the early stages of the project. The results show the impact of this role for care homes with poorer CQC ratings. The role is particularly valued by the local authority owing to the support provided following their own, and CQC, monitoring and safeguarding reports. Those care homes who have received support prior to CQC inspections, have also benefited from the team who have highlighted areas for improvement and provided support in these areas.

When developing this role, it was important that the technicians were flexible in their approach with care homes and were responsive to their needs, as well as those of, for example, the local authority. It was particularly important to be clear that the team’s role was to provide support and was not a monitoring function and not to add to the workload, legislation and requirements the care home was already required to meet.

Overall, the feedback on this aspect of the service has been positive. The majority of care home managers have welcomed the support. Feedback shared by care home managers, both informally and formally, via the local authority care home forum has facilitated the team to initiate support with new care homes, overcoming some of the concerns managers may have about staff coming into their environment to review the care being provided to residents.

Limitations

With regard to medication reviews, the data are insufficient to inform a full review of cost-effectiveness. Return on investment has been calculated using actual staffing costs for both pharmacists and technicians giving a return on investment of 2.7. However, there are also likely to have been secondary savings that have not been calculated (e.g. admission avoidance). Other studies have calculated savings on admission avoidance using RiO scoring adapted from the hospital avoidance scale[47]

. This was not utilised within this service as the Wigan medicines optimisation QIPP approach, savings related to avoiding events, have not previously been calculated. If adoption of this approach was considered, training and peer review would be required to ensure scoring was both appropriate and consistent.

In addition, the time taken to complete each medication review was not recorded. The team is currently considering how this can be achieved and what this should include (e.g. time collating information from MAR charts, discussions with residents and care home staff, GP time, time spent ensuring documentation at the care home is updated following review, liaison with community pharmacies). Future research should compare different ways of working to identify the most effective and time-efficient process.

Data regarding time spent supporting care homes were not collected, although data regarding the number of visits each home has received are available. The time spent in care homes, developing SIPs, reviewing policies and procedures and developing staff training would be useful to support evaluation of the service.

Although there is anecdotal feedback on the service from GP practices, care home staff, CQC inspectors and local authority staff — all of which is positive — there is currently no formal feedback process. This is under development with the aim to obtain feedback from care home staff and managers following support from the technicians, GPs and care home residents on the medication review process. This will inform future service evaluation and identify areas for development and improvement.

Conclusion

Through a collaborative multidisciplinary approach, the care home team has successfully reviewed prescribing for care home residents and addressed inappropriate polypharmacy. There was a 15.8% reduction in the number of prescribed regular medications overall (reducing the mean number of regular medications from 9.4 to 7.9 per person). The resulting improvements in several key quality-prescribing indicators and patient safety has led to better person-centred care.

Developing the role of the care-home pharmacy technician has been particularly successful. Care homes have been supported to implement policies and procedures to improve the safe, efficient use of medicines, resulting in improved CQC ratings. The feedback from care home staff, CQC inspectors and the Local Authority Oversight Team has been extremely positive, with the team now embedded in monitoring and improvement processes locally. Although CCGs are not responsible for monitoring or regulation of care homes, the approach used demonstrates it is possible for CCG staff to work with care homes to improve outcomes for older people, and to support social care colleagues meet their obligations.

Financial and conflicts of interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Age UK. Later Life in the United Kingdom. 2016. Available at: www.ageuk.org.uk/Documents/EN-GB/Factsheets/Later_Life_UK_factsheet.pdf?dtrk=true (accessed March 2018)

[2] Wigan Council. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment for the Borough of Wigan. Chapter 2: Overview of Wigan’s Older People’s Social Care Needs, Service Costs and Requirements. 2011.

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. 2016. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-2615543103 (accessed March 2018)

[4] British Geriatrics Society. Quest for Quality. 2011. Available at: www.bgs.org.uk/campaigns/carehomes/quest_quality_care_homes.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[5] Duerden M, Avery T & Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation: making it safe and sound. The Kings Fund, 2011. Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Managing medicines in care homes. 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc1 (accessed March 2018)

[7] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. The right medicine: improving care in care homes. 2016. Available at: www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Publications/The%20Right%20Medicine%20-%20Care%20Home%20Report.pdf?ver=2016-10-19-134849-913 (accessed March 2018)

[8] Avery T, Barber N, Ghaleb M et al. Investigating the prevalence and causes of prescribing errors in general practice: The PRACtICe Study. General Medical Council, 2012. Available at: www.gmc-uk.org/Investigating_the_prevalence_and_causes_of_prescribing_errors_in_general_practice___The_PRACtICe_study_Reoprt_May_2012_48605085.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[9] Barber ND, Alldred DP & Raynor DK. Care home use of medicines study: prevalence, causes and potential harm of medication errors in care homes for older people. BMJ Quality & Safety 2009;18(5). doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.034231

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines management in care homes. Quality Standard (QS85). 2015. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs85 (accessed March 2018)

[11] Zermansky AG, Alldred DP, Petty DR et al. Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly people living in care homes a randomised trial. Age Ageing 2006;35(6):586–591. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl075

[12] Banerjee S. The use of antipsychotic medication for people with dementia: time for action. Department of Health, 2009. Available at: www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Antipsychotic%20Bannerjee%20Report.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[13] Department of Health. National Service Framework for Older People. 2001. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/198033/National_Service_Framework_for_Older_People.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[14] PrescQIPP. Care Homes — medication and falls. 2014. Available at: www.prescqipp.info/care homes-medication-and-falls/send/138-care homes-medication-and-falls/1715-bulletin-87-care homes-medication-and-falls (accessed March 2018)

[15] Darowski A, Dwight J & Reynolds J. Fall Safe, Medicines and Falls in Hospital: Guidance Sheet. 2015. Available at: www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/fallsafe-resources-original (accessed March 2018)

[16] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines optimisation: Key therapeutic topics. 2017. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-advice/Key-therapeutic-topics/KTT-2017-compiled-document.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[17] de Gage SB, Moride Y, Ducruet T et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: case-controlled study. BMJ 2014;349:g5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5205

[18] Frisher M, Gibbons N, Bashford J et al. Melatonin, hypnotics and their association with fracture: a matched cohort study. Age Ageing 2016;45(6)801–806. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw123

[19] Weich S, Pearce HL, Croft P et al. Effect of anxiolytic and hypnotic drug prescriptions on mortality hazards: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:g1996. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1996

[20] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Knowledge Summaries - Benzodiazepine and z-drug withdrawal. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/benzodiazepine-and-z-drug-withdrawal#!scenario (accessed March 2018)

[21] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Drug Safety Update (May 2012). Available at: www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/antipsychotics-initiative-to-reduce-prescribing-to-older-people-with-dementia (accessed March 2018)

[22] PrescQIPP. Bulletin 92: Safety of long term proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). May 2015. Available at: www.prescqipp.info/safety-of-long-term-ppis/send/166-safety-of-long-term-ppis/1942-bulletin-92-safety-of-long-term-ppis (accessed March 2018)

[23] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture. 2012. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg146 (accessed March 2018)

[24] PrescQIPP. Bulletin 110: Bisphosphonate treatment breaks. 2015. Available at: www.prescqipp.info/resources/send/245-osteoporosis-bisphosphonate-treatment-breaks/2389-b110-bisphosphonate-treatment-break (accessed March 2018)

[25] Department of Health. Bisphosphonates use and safety. 2014. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/bisphosphonates-use-and-safety/bisphosphonates-use-and-safety (accessed March 2018)

[26] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Quality Standard Osteoporosis (QS149). 2017. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs149/chapter/Quality-statements (accessed March 2018)

[27] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Atrial fibrillation: management. 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180 (accessed March 2018)

[28] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Atrial fibrillation: management resources. 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180/resources/patient-decision-%20aid-243734797 (accessed March 2018)

[29] UK Inhaler Group. Inhaler standards and competency document. 2016. Available at: www.respiratoryfutures.org.uk/media/69774/ukig-inhaler-standards-january-2017.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[30] Murphy A. How to help patients optimise their inhaler technique. Pharm J 2016;297(7891):online. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201442

[31] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Asthma Quality Standard (QS25). 2013. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs25 (accessed March 2018)

[32] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults Quality Standard (QS10). 2011. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs10 (accessed March 2018)

[33] Greater Manchester Medicines Management Group. Polypharmacy Guidance 2016. Available at: http://gmmmg.nhs.uk/docs/guidance/NWCSU-Polypharmacy-guidance-2016.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[34] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. 2009. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76 (accessed March 2018)

[35] NHS England. Better Care Fund. Available at: www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/part-rel/transformation-fund/bcf-plan/ (accessed March 2018)

[36] Swift A. NICE Shared Learning Database. 2015. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/medicines-optimisation-peer-review-programme-engaging-gp-practices-to-deliver-medicines-optimisation-and-implement-nice-guidance (accessed March 2018)

[37] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Managing medicines in care homes. Tools and resources. 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/sc1/resources (accessed March 2018)

[38] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. 2015. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-6775454 (accessed March 2018)

[39] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Handling medicines in social care. 2007. Available at: www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Support/toolkit/handling-medicines-socialcare-guidance.pdf?ver=2016-11-17-142751-643 (accessed March 2018)

[40] Department of Health. QIPP. The National Archives. 2013. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130104162058/http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/category/policy-areas/nhs/quality/qipp/ (accessed March 2018)

[41] Care Quality Commission. The state of health care and adult social care in England. 2015–2016. Available at: www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20161019_stateofcare1516_web.pdf (accessed March 2018)

[42] Care Quality Commission. The five key questions we ask. 2017. Available at: www.cqc.org.uk/content/five-key-questions-we-ask (accessed March 2018)

[43] Ryan R, Santesso N, Lowe D et al. Interventions to improve safe and effective medicines use by consumers: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD007768. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007768.pub3

[44] Bain T. Anticholinergic burden — tracking adverse effects. Aging Well 2011;4(2):8. Available at: www.todaysgeriatricmedicine.com/archive/spring2011_p8.shtml (accessed March 2018)

[45] PrescQIPP. Anticholinergic drugs. 2016. Available at: www.prescqipp.info/resources/send/294-anticholinergic-drugs/2864-bulletin-140-anticholinergics-drugs (accessed March 2018)

[46] Baqir W, Barrett S, Desai N et al. A clinico-ethical framework for multidisciplinary review of medication in nursing homes. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2014;3(1). doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u203261.w2538

[47] NHS Croydon CCG. Specialist Pharmacy Service. Croydon explanatory document. 2017. Available at: www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Croydon-explantory-doc.pdf (accessed March 2018)

<div class=”ad siteBanner”> <div class=”sponsoredAd sponsored”> <div class=”sleeve”> <p class=”heading”> A new series of ebooks from <em> The Pharmaceutical Journal </em>. The first book in the series focuses on the care of older patients.

</p> <div class=”sub”> <div class=”image”> <a href=”https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/publications/cpd-kindle-edition/“> <img alt=”ebook cover old age v3” src=”/Pictures/web/k/r/m/ebook-cover-old-age-V3.jpg” /> </a> </div> </div> </div> </div></div><p> Advertisement</p>