Abstract

Aim

To investigate the role of the medicines counter assistant in the sale of over-the-counter medicines.

Design

Qualitative study using two methods of data collection: (1) non-participant observation and (2) semi-structured interviews.

Subjects and setting

Medicines counter assistants and customers purchasing OTC medicines in a number of community pharmacies in Bristol and South Gloucestershire.

Outcome measures

(a) How counter assistants manage the retail and clinical dimensions of their role, (b) how counter assistants use pharmacy protocols and the extent to which they use their own judgement when making OTC sales, (c) how counter assistants respond to customers who are unwilling or unable to provide full information.

Results

The data showed that counter assistants successfully perform a primary care function. They respond to requests for advice, they recommend OTC and GSL medicines and they perform a risk mediation service for customers requesting products. However, data also showed that dialogue between customers and counter assistants can be problematic.

Conclusion

The research shows that the counter assistant is an effective facilitator in the supply of OTC medicines and is generally recognised as such by customers. However, the research also highlighted problems with the use of pharmacy protocols. We suggest that the protocol may be too rigid a tool to facilitate effective communication between customers and pharmacy staff.

In this paper we examine the role of the pharmacy medicines counter assistant (MCA) in relation to the important changes that have affected community pharmacy. The role of the MCA has changed alongside changes to the role of the community pharmacy which, since the 1990s, has been promoted as an alternative site of primary care. People are now encouraged to visit their local pharmacy for advice on minor ailments. A key factor in expanding the pharmacy’s role beyond a “dispensing outlet” has been the increasing numbers of pharmacy medicines made available to sell over the counter.1 A number of medicines, formerly available on prescription only, have been reclassified as P medicines. Community pharmacies now have a wider range of pharmaceutical products available for direct sale to customers seeking medical advice and treatment.

These changes have shifted the role of the MCA away from retail sales toward a health care role. Their role now involves advising people on suitable medicines for their ailments and the safe and effective use of medicines requested by customers. Although MCAs are formally under the supervision of pharmacists, research has shown that they, more than pharmacists, deal with requests for OTC medicines.2 The burgeoning responsibilities incumbent on MCAs were recognised by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in 1996 when it formalised training programmes for MCAs.3

The developing role of the community pharmacy is reflected in a wide body of research papers. Of particular relevance here are Bissell et al,2 who identified a high degree of variation in the provision of advice when selling OTC medicines. Subsequent authors have also highlighted the resistance of customers to receiving advice or answering questions4 and also whether customers recognise the legitimacy of pharmacy staff to perform a medical role.5 Ward et al6 highlighted the increased ambiguity of the MCA, whose role encompasses a retail sales dimension and a health care dimension. Overall, research has shown the role of the MCA to have problematic aspects, some of which may be linked to the role’s “early” stage of development.

In this paper we will examine the development of the MCA as a health care worker and develop the research themes identified above. The data in this paper are drawn from a qualitative research project that examined the development of the MCA as a health care worker in the context of the changing role of the community pharmacy. The project was based on non-participant observation of MCAs and pharmacy customers and semi-structured interviews with MCAs. This paper is based on both forms of data, with a particular focus on the interview data. A separate paper will develop the qualitative observation data in more detail.

Methods

Six community pharmacies in and around Bristol were recruited as research sites for the project. These were purposively sampled7 to ensure a range of pharmacy types. Of the six pharmacies studied: four were multiples (two were “in store”) and two were independents; three pharmacies were in an urban location and three were suburban. Across the six pharmacies, 479 interactions between customers and MCAs were observed and 22 MCAs were interviewed. All the MCAs interviewed worked in the six pharmacies studied and had been involved in the observation part of the research.

One of us (JB) carried out non-participant observation and interviews. We acknowledge that the presence of the observer can effect the behaviour of those participating in the study.8 This was minimised through lengthy discussions with the participants before starting the observations, emphasising that we were not auditing their behaviour on behalf of their employers and that their identities would be anonymised in any reports or publications. During quieter periods the researcher engaged in informal dialogue with MCAs and pharmacists about their work and other issues to ensure they felt comfortable with the researcher’s presence.

Fifteen hours of non-participant observation were spent in each pharmacy in five three-hour blocks. The timing of the three-hour blocks was varied over a two-week period and data were recorded during morning and afternoon sessions. The observation was usually undertaken from behind or to the side of the pharmacy counter alongside the MCAs and in full view of the customers. We collected data on the purchase of OTC medicines and the provision of medical and pharmaceutical advice by pharmacy staff. Following Bissell et al2 we classified giving advice or asking questions as anything that related to medical or pharmaceutical issues rather than retail issues. Data were recorded by field notes.

The interviews were semi-structured, lasted 20–45 minutes and were undertaken by JB. Topic covered in the interviews included:

- Changes to MCAs’ role

- MCAs’ views on the use and effectiveness of pharmacy protocols

- MCAs’ working relationships with phamacists

- MCAs’ views on the increased range anduse of OTC medicines

- MCAs’ views on the “social support” they provide in their local communities

Interviews were recorded at the research sites where the MCAs were employed, usually in a back room or a staff rest room with no other persons present. Interview data were audio-recorded and fully transcribed. Analysis of the interview data followed the principle of the constant comparative method9 whereby data were subject to multiple readings to facilitate familiarity and the identification of broad analytical themes. Data were then organised into codes and categories and subsequently reanalysed using the iterative, cyclical process central to qualitative research.10 Atlas.ti, a qualitative software analysis tool, was used to manage the data. The coding framework was cross checked with other qualitative researchers on the research team (MW and AS). For the observational data, field notes were primarily analysed qualitatively, using a similar approach as for the interviews. However, a basic statistical outline was also established to provide a quantitative “flavour” of the types of interactions. The two sources of data (interviews and observation) enabled us to triangulate our findings8 and emerging themes from one data set were developed by comparing with the other. Ethical approval was granted for the research from two NHS local research ethics committees.

Results and discussion

We will outline our findings in three different areas:

- How MCAs manage the retail and clinical aspects of their role

- The use of pharmacy protocols

- How MCAs deal with customers who are reluctant to give full information

Basic descriptive statistical data from the observations are used to illustrate the type of interactions that took place across the pharmacies and qualitative interview data are used to develop the key emerging themes. The qualitative observation data will be reported elsewhere.) The numbers in brackets at the beginning of the data extracts refers to the numerical ID assigned to the MCAs who participated in the research.

Managing the retail and the clinical aspects

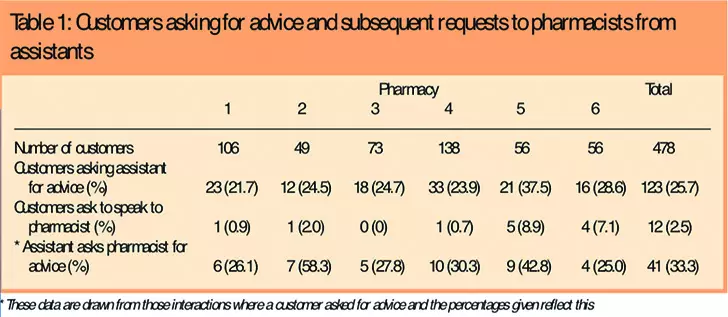

Around a quarter (123/478, 25.7 per cent) of the customers recorded in the observation data came to the pharmacy seeking advice and treatment for minor ailments. MCAs undertook this role with a high degree of autonomy, usually giving advice and recommended medicines without consulting the pharmacist. MCAs consulted the pharmacist on 41/123 interactions (33.3.per cent) where the customer asked for advice, so therefore acted independently on 82 occasions (66.7 per cent).

Observation data also indicated that people were generally happy to talk direct to an MCA about their ailment. Less than 3 per cent of interactions (12/478) featured customers asking to speak direct to the pharmacist. This suggests that MCAs are recognised as a source of advice on medical and pharmaceutical matters.

Interview data highlighted how the primary care aspect of the MCAs work had developed. MCAs who had worked in pharmacies for over five years indicated that their role and the role of the pharmacy in general had taken on more of a medical character. This change was linked to changes in the status of community pharmacies and the deregulation of medicines from POM to P status and is illustrated in the comments below:

MCA (4): That was the sort of big thing, you didn’t ever ask any questions to the patient, you just said xxx, you know, and you spent all day shouting out the P medicines and the pharmacist would either totally ignore you or um, you know, it would be going in and obviously he would be looking up …it has changed in that you now are expected to ask the (xxxx) questions and you tend to just get into the habit of doing it really, over the years.

MCA (18):There are a lot of people come in and, you know, do that, ask for things for various symptoms. I think a lot of people feel it’s something they don’t want to bother the doctor with so if they can get something over the counter they, a lot of them will do that, it’s the first thing.

As the latter quote illustrates, MCAs also believed that people were increasingly using pharmacists and MCAs as an initial point of contact for health problems, thus reinforcing the developing primary care aspect of the role.

Interview data showed that MCAs were generally positive about their role. MCAs highlighted the stimulating nature of the role, which involved learning about medicines and evaluating the suitability and safety of medicines for individual customers. MCAs emphasised the value of variety, with customers presenting with a range of individual queries and problems. A number of MCAs spoke about the status afforded them by the position: they compared it positively to other retail positions they held or had held. Comments by MCAs on the negative aspects of the role tended to be restricted to complaints about rude and difficult customers (see later). The comments below give a flavour of MCAs’ positive endorsement of the role:

MCA (1): Mm, I really enjoy it yeah, I find it quite a challenge and very rewarding as well.

MCA (7): I think it’s quite interesting because obviously every customer’s different. And every customer’s got different needs. Two customers might come in with the same sort of symptoms but it all depends on, basically what they’re taking already or if they’re asthmatic or something like that and you’ve got to sort of advise them on something different, so it’s not the same, like 10 people could come in and you wouldn’t actually tell all those 10 people to take the same item so it is quite varied.

MCA (10):Comparing it to what I used to do it’s a lot more interesting, you get to talk the customers. They respect you more.

The MCAs in this study showed that they have successfully adopted, and welcomed, the medical dimension of their role. When asked for advice they undertook a clinical dialogue in that they were using pharmaceutical and medical knowledge in their interactions with customers. They would consult the pharmacist when they were unsure about something but the data show that most of the time they undertook their advisory work autonomously.

Pharmacy protocols

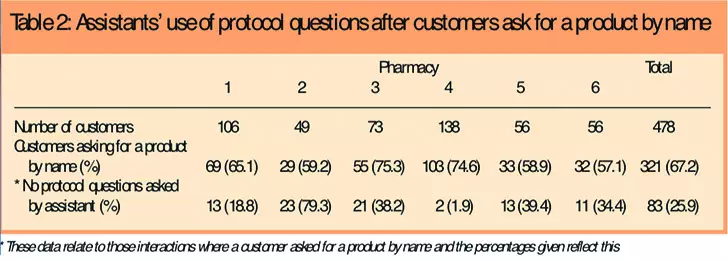

The observation data showed that 67 per cent of OTC interactions (321/478) feature customers asking for products by name (Table 2).

Here, the customer employs a retail discourse: customers come to the counter to buy a product rather than to seek medical or pharmaceutical advice. The MCA also performs a clinical role in this type of interaction, because they have to ensure that the medicine requested is to be used safely and effectively by following pharmacy protocols.11 Within this type of interaction the MCA is still engaged in a health care role but it takes on the form of risk mediation: the MCA evaluates risk on the basis of information they receive from the customer.

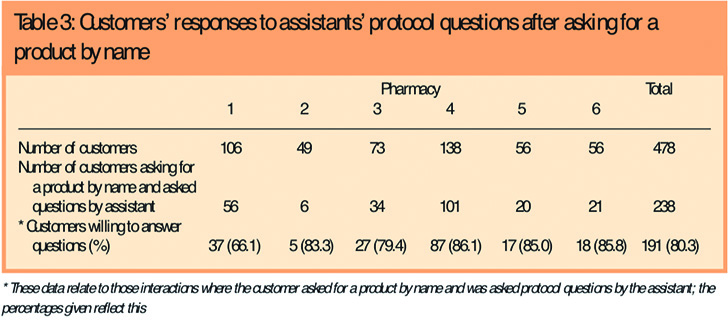

Table 2 also shows that MCAs asked questions in 238 of the 321 encounters of this type (74.1 per cent). Most of the interactions observed (191/238 or 80.3 per cent of those who asked for a product by name and were questioned by the MCA [see Table 3]) featured customers who were cooperative in answering the questions asked by the MCA. In interviews MCAs also thought that most people were comfortable about being questioned when purchasing P medicines and they were generally positive about the protocol. However, there were exceptions (see later).

There were occasions when the protocol was not used, when a customer asked for a product and MCAs made a sale without asking any protocol questions. Such interactions took on a retail rather than a medical/pharmaceutical character. There are a number of possible explanations for this. The MCA may have prior knowledge of the customer and know his or her medical background — both Ward et al6 and Bissell et al2 discuss how this shapes interactions within the pharmacy — or they may avoid questions because they know that the customer is hostile to them. Although not excluding these explanations, our research data point in two particular directions.

First, the working culture of the pharmacy will shape the degree to which questions are asked or not. As shown in Table 2, at research site 4, less than 2 per cent (2/103) of interactions where a product by name was requested featured no questions and research site 2 had nearly 80 per cent (23/29). However, the other sites featured a level of non-questioning between 18 and 40 per cent, which indicates that the working culture of the pharmacy only gives a partial explanation.

Secondly, the data showed that most interactions across the six pharmacies that featured no questions involved requests for medicines that were available in smaller quantities as GSL products available from non-pharmacy outlets with no formal protocols associated with their purchase. They are closer to what Harding and Taylor12 describe as ordinary retail objects. The non-questioning associated with these medicines points toward an informal downgrading to ordinary objects by the MCA. This explanation is given some credence by interview data that highlight the frustration felt by some MCAs over having to ask questions for what seem like everyday products:

MCA (11):You’re supposed to ask — even for something like Calpol — have they had it before? And I mean every kid under the sun has had Calpol over the age of three months, so we don’t usually ask that one then because you think well all kids, that’s a daft question because they’ve all had Calpol.

This explanation also points toward MCAs incorporating a level of autonomy in their role. The MCA is making a judgement about the suitability of questions being asked rather than automatically delivering the questions.

Managing reluctant customers

The observation data show that the biggest problem experienced by MCAs was customers who were reluctant to answer MCAs’ protocol questions. Of the customers that asked for a product by name and received some degree of questioning by the MCA, nearly 20 per cent (47/238) displayed evidence of dissatisfaction about being questioned. During observations, dissatisfaction was evident in subtle signs of resistance: the tone of a customer’s voice may have been distant or answers to questions were delivered in a snappy manner that cut MCAs’ questions short. Customers would also use negative body language such as looking around the shop during the MCAs questions. These non-verbal cues or signs indicating resistance to questioning were supported by data from MCA interviews as illustrated below:

MCA (7): Sometimes you just detect it in the way they answer as if to say, yes, of course I’ve taken it before, but we don’t know that, so we have to ask. Like they, it’s as if they can’t be bothered to answer, they do, but they, I don’t think I’ve had one where they’ve got uptight or annoyed but you just sometimes detect it in their mannerisms . . . So we just say you know, well we have to ask because obviously we want to make sure that we’re not giving you something you shouldn’t be taking.

MCAs expressed a sense of powerlessness when the customer is saying the right things in terms of the protocol but they are not conveying credibility in their answers:

MCA (15): I suppose you do sort of think oh, God. I know that they’re going to be buying that hydrocortisone for their face when they shouldn’t be putting it on their face. But what can you do? I mean who’s to say that if they were given it on prescription they wouldn’t anyway, you can tell them and you can advise them that you shouldn’t be using this and if it goes on for more than X amount of days then you need to go back to the doctor, but I’m sure a lot of people just say yes, yes, yes.

MCAs outlined various informal methods they had developed to create a more meaningful dialogue: some MCAs described a process of extending and rewording questions until they felt they had received satisfactory responses. Others would ask questions or give advice as they were processing the sale (taking money, giving change, putting the product in a bag) thereby indicating to the customer that the sale was not threatened by the questions. All of these factors gave MCAs a greater sense of “making a safe sale”, which is evident in the comment below:

MCA (4): There are the few people who, just think well it’s none of your business really. You tend to just say, have you used it before . . . and you know that they don’t actually want to give . . . so at that stage, when I’m putting it in the bag and giving it to them I just say ‘make sure you don’t take anything else with paracetamol in’ because I feel then that I’ve done my job and I haven’t antagonised them by saying ‘well are you on any other medication’ because you know that they don’t actually want to answer those questions.

In interviews all MCAs said they would consult the pharmacist if they were concerned that a customer was abusing or becoming over-reliant on a medicine. MCAs indicated a variety of responses from pharmacists in such circumstances. These included: approving the sale as long as the protocol has been satisfied, approving the sale but removing the item from view (giving the option of saying “it’s not in stock” when the customer returns) and challenging the customer about their use of medicines.

Conclusion

The data showed that the MCAs who participated in the research successfully performed a primary care function, responded to requests for advice, recommended OTC and GSL medicines and undertook a risk mediation service for customers requesting products.

Interview data showed that MCAs were generally positive about the medical and pharmaceutical aspects of their work. In most interactions the customers recognised the legitimacy of the MCA to ask questions about symptoms and pharmaceuticals consumption. Most of the time MCAs’ work was unproblematic in terms of their relationship with customers in that customers positively engaged with the questions asked by the MCA.

MCAs were generally positive about using protocols. However, there were a number of occasions in which they did not use a protocol and the explanations supported by our data were:

- The working culture of individual pharmacies shaped the pattern of protocol use by MCAs

- MCAs tended to use the protocol less when responding to requests for OTC medicines that were also available as GSL medicines

There were a small but regular number of occasions in which dialogue between customer and MCA was made problematic by customers’ reluctance to answer or fully engage with the protocol questions asked by the MCA. Interview data showed that MCAs often encountered customers who would say all the right things in terms of the protocol but their manner lacked the conviction that would enable the MCA to believe they had made a safe and appropriate sale. MCAs used a number of informal methods to create more meaningful dialogue when there was resistance to questioning.

The research set out to examine the role of the MCA against a backdrop of change in the field of community pharmacy practice. Our data showed MCAs to be effective facilitators in the supply of OTC medicines who gave appropriate medical and pharmaceutical advice for their use. However, MCAs work in a retail environment and encounter customers who do not recognise the need to engage in health-related discourse. MCAs also exclude health-related discourse when they do not think it is appropriate. This suggests that the use of pharmacy protocols is problematic. Berg13 has pointed out that the protocol may be too rational a tool for use in medical consultations because it fails to address the complex social and individual dynamics that come to bear upon particular interactions between health professionals or health care workers and patients or customers. Following Ward et al6 we argue that training for MCAs may need to be developed so that MCAs engage in complex issues surrounding medicines communication, with particular emphasis on handling situations where the customer is reluctant to answer questions.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a grant from the Proprietary Association of Great Britain. The authors gratefully acknowledge the help and support they received from the pharmacies and medicines counter assistants who participated in this study. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the Proprietary Association of Great Britain.

This paper was accepted for publication on 3 February 2005.

About the authors

Jonathan Banks, PhD, is research associate and Alison Shaw, PhD, is lecturer in the department of community medicine at the University of Bristol. Marjorie C. Weiss, DPhil, MRPharmS, is senior lecturer in the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath.

Correspondence to: Dr Banks at Department of Community Medicines, University of Bristol, Cotham House, Cotham Hill, Bristol BS6 6JL (e-mail jon.banks@bristol.ac.uk)

References

- Bond C. POM to P — implications for practice pharmacists. Primary Care Pharmacy 2001;2 5–7.

- Bissell P, Ward PR, Noyce PR. Responding to requests for over-the-counter medicines. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy 1997;14:1–15.

- Flint J. Training requirements for medicines counter assistants. Pharmaceutical Journal 1996;256:858–9.

- Hibbert D, Bissell P, Ward PR. Consumerism and professional work in the community pharmacy. Sociology of Health and Illness 2002;24:46–65.

- Seston EM, Nicolson M, Hassel K, Cantrill JA, Noyce PR. Not just someone behind the counter: the views and experiences of medicines counter assistants. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2001;18:122–8.

- Ward PR, Bissell P, Noyce PR. Medicines counter assistants: roles and responsibilities in the sale of deregulated medicines. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 1998;6:207–15.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. (2nd edition). London: Sage;1990.

- Hammersly M, Atkinson P. Ethnography. Principles in practice (2nd edition). London: Routledge; 1995.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research (2nd edition). London: Sage; 1998.

- Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research: observational methods in health care settings. BMJ 1995;311:182–4.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Medicines, ethics and practice: a guide for pharmacists (issue 27). London: The Society; 2003.

- Harding G, Taylor K. Responding to change: the case of community pharmacy in Great Britain. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1997;19:547–60.

- Berg M. Problems and promises of the protocol. Social Science and Medicine 1997;44:1081–8.