Shutterstock.com

The pharmacy degree may be the lifeblood of the profession, but there are the first signs of anaemia.

The Pharmaceutical Journal has learnt that education chiefs are increasingly worried about the popularity of the MPharm degree amid rising competition for degree courses.

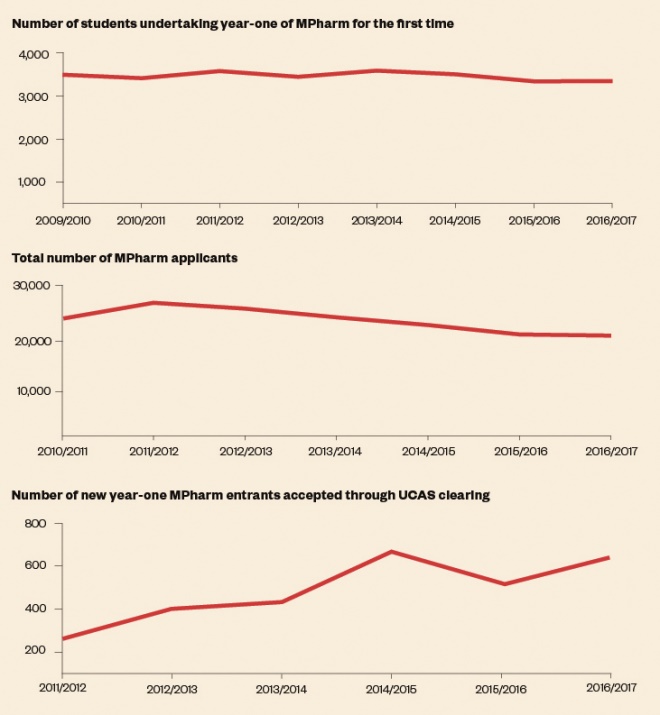

The latest figures available show a sizeable drop in applications and, as a result, pharmacy schools are becoming increasingly reliant on the university clearing system to fill their courses, with a 140% increase in places gained through this process (see Figure).

This is leading to concerns that hundreds more students are beginning the MPharm without the required grades compared with five years ago. The General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) has suggested that this may be a factor in high failure rates for students taking the preregistration assessment for the first time and is proposing that pharmacy schools must explain their decisions if they lower their entry criteria to fill places.

In 2016/2017, the number of students applying to study for the vocational MPharm degree was 21,104, the lowest figure in the past seven years and a 14% drop over that period. The number of first-year MPharm students has stayed relatively constant, although 2016/2017 saw the second lowest figure since 2009/2010. Figures for 2017/2018 were not available.

Tough competition

Several heads of pharmacy schools acknowledge that student recruitment is becoming tougher as they compete for potential students from the same pool as medical schools and from among the limited number of school-leavers with A-Level sciences.

Clive Roberts, head of the school of pharmacy at the University of Nottingham, says all schools realise that there are fewer students applying for pharmacy and that they all have to work harder to recruit. The issue is compounded by competition from other subjects and a dip in the number of 18-year-olds in the UK, which is projected to continue falling until 2020.

In the past five to ten years there has been a lot of negative press about pharmacy which has come home to roost

“Pharmacy schools are talking about this,” says Roberts. “There is competition from other subjects – medicine is one obvious area. I think in the past five to ten years there has been a lot of negative press [about] pharmacy which has come home to roost. We are in a very competitive space but we manage to hold on to our tariff and our numbers. We are at the top end of things which may have assisted us in being a bit more resilient.”

The school has used the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) “adjustment” system — where students who have exceeded their expected grades can look for an alternative course — to fill around 10–15 places annually for the past four or five years. But Roberts added: “We get higher tariff students through adjustment than we do through the normal process. Students today understand the value of their tariff and don’t make a decision [about which course to apply for] until they know what they have got.”

Duncan Craig, director of the UCL school of pharmacy in London, admitted that the “pool of talented students is reducing in size”, but he said his school had not used the clearing process to fill its places.

“There are almost certainly less students applying; the reasons are likely to be multiple, but poor morale in some sectors of the profession, which is being communicated to applicants, is quite possibly a key consideration,” says Craig. He adds that the profession also had to understand that “every time a colleague tells a young person that the profession does not represent a favourable future for them that they are then creating a self-fulfilling prophecy”.

Paul Grassby is head of the new pharmacy school at the University of Lincoln, which accepted its first MPharm students four year ago. He says: “When we went through clearing this year I was more worried about going over our numbers — we picked up a few students but not a substantial number. I think last year nearly every pharmacy school was in clearing and it’s been an issue.”

The Pharmaceutical Journal also contacted the University of Central Lancashire; Kingston University, London; the University of Wolverhampton; the University of Brighton; the University of Portsmouth; and the University of Hertfordshire, but no one was available for comment.

Turning to clearing

The trend to turn to UCAS clearing to find students has grown over the past five years and some medical schools are now facing the same situation. UCAS figures for all undergraduate degrees show that by 13 September 2018, 53,360 students were placed through clearing, compared with 47,830 students in the summer of 2013.

Figures from the GPhC show that 643 first-year MPharm students were taken on though clearing in 2016/2017, compared with 265 students in 2011/2012 — a 143% increase.

Nigel Ratcliffe is chair of the Pharmacy Schools Council, which represents the UK’s 30 pharmacy schools. He told The Pharmaceutical Journal: “More universities are going through clearing to fill their places than there have been before as the number of pharmacy schools has increased, as well as the number of student places having increased in existing schools.”

Source: Courtesy of Nigel Ratcliffe

Nigel Ratcliffe, chair of the Pharmacy Schools Council, says institutions that are recruiting students through clearing need to be careful that they choose students with the right qualifications who actually want to be pharmacists

Ratcliffe, who was until recently head of the school of pharmacy at Keele University, adds: “Competition [to fill places] is much tougher today; therefore, universities need to continue to be careful that they are recruiting individuals who want to be pharmacists and that these individuals have the right qualifications and understanding of professional values.

“Finding students through clearing can be fine provided there is a mechanism to ensure that when people graduate and go on to the register that there is a very high minimum standard of knowledge and skills assured.”

This has led to the GPhC expressing concerns over the number of pharmacy graduates who are not passing the preregistration assessment on their first attempt, and it has queried whether pharmacy schools should only accept students who have achieved the required advertised grades.

In November 2018, the GPhC produced proposals to overhaul the education and training standards for pharmacists, which set out how the GPhC is concerned “that around 20% of people have not passed the registration assessment at their first sitting in the past two years”. It says that while there may be a number of reasons for this, the “wider trend” of students beginning university courses “without achieving the advertised grades” may well be a factor.

In its proposals, the GPhC says: “That raises the question of whether our standards should require course providers to admit only those students who have demonstrated their academic ability by achieving the A Level/Highers grades advertised for a course.”

But the GPhC concludes that schools should instead set criteria for accepting students who do not achieve advertised grades.

And the proposals for the future education of pharmacists also say that schools of pharmacy “will be required to have effective measures in place to ensure that, whatever students’ academic performance upon entry to the course, only those who have demonstrated over five years that they are capable of achieving the standard required for registration actually progress to graduation”.

High standards

Malcolm Harrison, chief executive of the Company Chemists’ Association, which represents the major high street pharmacy chains and supermarket pharmacies, says the increasing number of students coming through clearing “is a concern”.

We’re really keen that there is a robust pipeline of professional talent that we can bring through to enable us to deliver care for patients

“We need to make sure that we’re able to ensure that pharmacy professionals coming through are of the right standard that we would expect or need to enable them to deliver the care that we need,” he says.

“We have businesses that we’re trying to support in providing medicines and care for patients and without professionals there to provide that care, it becomes really difficult to perform that function. So we’re really keen that there is a robust pipeline of professional talent that we can bring through to enable us to deliver care for patients. Without that, things become difficult to run.”

Source: Courtesy of Malcolm Harrison

Malcolm Harrison, chief executive of the Company Chemists’ Association, says part of the problem is that the number of pharmacy schools has ballooned in recent years

Harrison adds that part of the issue was “market forces coming into play” with the number of pharmacy schools having “ballooned in recent years”.

According to the Pharmacy Schools Council, the number of pharmacy schools increased from 26 schools in 2013 to 30 schools in 2018, but the number of students entering the first year of the MPharm has reduced by 7% in recent years, from its peak in 2013/2014 (see Figure).

Figure: How the pharmacy school intake has changed

Source: General Pharmaceutical Council

Note: the graphs are not a direct comparison and should be interpreted separately

The contribution of the expansion of schools leading to difficulties in recruitment may well be borne out of the fact that one of those new schools — at the University of Sussex — announced in November 2018 that it was consulting staff over closing its pharmacy programme to new students. The university is proposing to close the programme from September 2019 because of its low student numbers “over a period of time”.

We have a responsibility to develop the future workforce and make it an attractive and an appealing career

The university, which began its MPharm programme only two years ago in 2016, said in a statement: “The demand to study pharmacy at the University of Sussex has been low over a period of time. Should the university ultimately decide to close the course to new entrants, we are committed to fully supporting our existing pharmacy students, including teaching out the course and supporting them into the workplace or further study.”

Attracting future pharmacists

Richard Bradley, pharmacy director at Boots, called for a “road map for pharmacy” to ensure it is an attractive profession that will attract students into the future. He told The Pharmaceutical Journal that the options available to young people with a scientific background in particular are far greater than they were a few years ago.

“We have a responsibility to develop the future workforce and make it an attractive and an appealing career,” he says. He added that in recent years, Boots has developed its “clinical pathways for careers” through the advanced practitioner role and by launching “a new role of specialist practitioner, which really recognises pharmacists who are delivering enhanced care locally”.

Despite the concern over pharmacy student numbers, Harrison maintains that there is a “bright future for pharmacy”, and work is going ahead to attract more young people into the profession (see Box).

“If we can land some of the ideas that are out there in terms of the role that pharmacists can provide, both within primary care and in other aspects of the healthcare system,” he says, “then pharmacy is a great career choice for people to make.”

Box: Promoting the pharmacy profession

Promoting pharmacy as a career should start young, says Duncan Craig, director of UCL School of Pharmacy, highlighting how a strategy to promote scientific careers in schools has been used to great effect by the Royal Society of Chemistry.

He says pharmacy bodies should also work with universities to demonstrate that “the pharmacy degree is a fascinating mix of science, clinical skills and personal development opportunities that renders the graduate capable of taking on a multitude of professional roles”.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) is becoming more proactive in promoting the profession. Chris John, head of workforce development at the RPS, says the RPS is working on a booklet that will be sent to all pharmacy schools “to attract people into MPharm programmes and promote what is now a very varied career”.

The booklet is “aimed at inspiring people into the profession” by detailing the main career paths available, such as community pharmacy, hospital pharmacy, industry and academia, as well as “some of the newer roles”. However, he clarified that the booklet was not produced in response to the declining numbers of MPharm students.

References