Andrea Ucini

On 1 February 2018, Australia’s national drugs regulator, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), banned the sale of all over-the-counter (OTC) medicines containing codeine from pharmacies[1]

.

It was a radical move designed to halt the rise in codeine-related deaths, which had increased from 3.5 per million population in 2000 to 8.7 per million population in 2009, and because of a lack of evidence that codeine at OTC doses is any more effective as an analgesic than non-codeine containing products[2],[3]

.

Australia is not the first country to take this step — 25 others, including the United States, Japan and the United Arab Emirates, have done the same[4]

. But despite this, concerns were raised over a complete ban. Some medical professional bodies — for example, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists — were strongly supportive, but pharmacy organisations voiced their reservations[1]

. The Pharmacy Guild of Australia argued that making codeine available on prescription only would unfairly affect people who genuinely need it and use it safely when bying it OTC[3]

.

An analysis of pharmaceutical industry sales data by the TGA has shown that re-scheduling codeine has resulted in a significant decrease in its supply. The number of codeine-containing products supplied during 2018 was approximately 50% lower than the average total supplied in the previous four years[5]

.

Justifying a ban in the UK

The UK’s Commission on Human Medicines — a committee within the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) — is currently carrying out a major review of the risks and benefits of opioid medicines[6]

.

The review, which is expected to conclude later in 2019, will consider whether efforts to minimise the risks of OTC and prescription opioid use have been effective. It was prompted by growing concern, both nationally and internationally, about increased prescribing and overuse of opioid analgesics.

There is some evidence that OTC codeine-containing medicines could be contributing to the problem of opioid overuse. In 2019, Fingleton et al. found that codeine-containing analgesics were the most common OTC medicine of dependence seen in specialist substance misuse treatment services[7]

.

However, overall, concrete evidence for increasing misuse of OTC opioids in the UK is lacking. Usage is not recorded at a national level and those who become dependent are often unaware they are addicted. This addiction is, therefore, often missed by healthcare professionals, leaving people at risk[8]

.

The MHRA has already taken some steps to raise awareness of the dangers of OTC opioid use. In 2009, tighter controls were introduced on OTC painkillers containing codeine or dihydrocodeine in order to minimise the risk of overuse or addiction[9]

. The changes included adding the warning “Can cause addiction. For three days’ use only” to the front of each pack and only allowing packs of 32 tablets or less to be available as pharmacy products. In April 2015, the MHRA recommended that children aged under 12 years should not be given OTC codeine.

Pharmacists were asked to support the measures by giving important safety messages about short-term use and avoiding addiction. However, as Cathy Stannard, a consultant in complex pain and the pain transformation programme clinical lead for NHS Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group, says, “the problem is, it is difficult to police”.

If someone is taking prescribed opioids and getting stuck on a high dose, at least they’re having a healthcare interaction with somebody

“If someone is taking prescribed opioids and getting stuck on a high dose, at least they’re having a healthcare interaction with somebody,” she says. Whereas those who get stuck on OTC codeine are “often quite busy, high-achieving working people — they just want to get on with their lives and before they know it, they’ve got a dependency”.

Scoping out the problem

Scotland has been making significant in-roads in defining OTC opioid dependency and what pharmacists can do to help prevent and manage it.

In 2016, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) in Scotland ran a series of opioid dependency workshops across health boards in response to feedback from pharmacists that this is a difficult area of practice.

The aim of the workshops, which were led by specialist pharmacists in substance misuse, was to help pharmacist attendees to identify, manage and reduce OTC- and prescription-opioid dependency and to provide advice on how to engage in conversations with customers suspected of opioid dependency (see Box 1).

“We asked everyone, can you think of two to three people who come in regularly [who are dependent on OTC opioids]? Everyone had a story and many reported people who had been harmed by their OTC use or where it was masking a ‘red flag’ condition,” Annamarie McGregor, practice development lead at RPS Scotland explains.

Courtesy of Annamarie McGregor

Annamarie McGregor, practice development lead at RPS Scotland, says that having conversations around dependency with users of OTC opioids is difficult but “extremely important”

A lot of OTC opioid users don’t think they’re dependent

But this could be just the tip of the iceberg. “A lot of [OTC opioid users] don’t think they’re dependent,” McGregor continues.

“It’s a difficult conversation, but an extremely important one.”

A 2015 study from Aberdeen University revealed that 80% of Scottish pharmacists believed OTC products were being misused in their pharmacies and the range of products available is increasing[10]

.

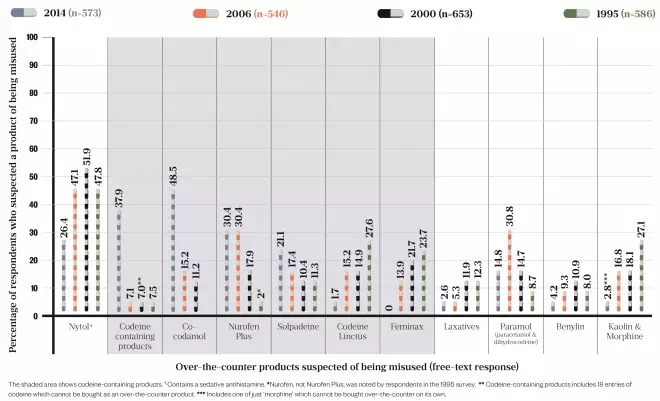

In the study, which was based on a cross-sectional survey posted to all community pharmacists in Scotland, codeine-containing products were mentioned in 95.8% of responses as being suspected of being misused. This was the first time that codeine topped the list for 20 years: in previous surveys, carried out in 2006, 2000 and 1995, the sleep aid diphenhydramine (Nytol) had been the most cited (see Figure).

Figure: Over-the-counter codeine overtakes Nytol as the product community pharmacists most suspect of being misused

Source: Wright J, Bond C, Robertson H et al.

[10]

Catriona Matheson, a substance use expert at the University of Stirling, convener of the Drugs Research Network Scotland and one of the authors of the study, says the most noticeable difference found when analysing more than 20 years of survey data is the increasing number of OTC codeine-containing products on the market.

Adult oral analgesics accounted for almost 15% of all OTC sales in Britain in 2017, with brands that include codeine-containing products in their portfolios topping the list of best-sellers (see Box 2)[11]

.

“What we’ve observed is that there’s a lot more variation in codeine-containing products. There are so many now that [contain] codeine as well as paracetamol and ibuprofen, the range of products is quite considerable,” Matheson adds.

Courtesy of Catriona Matheson

Catriona Matheson, a substance use expert at the University of Stirling, says that the range of codeine-containing products now available to buy over the counter is “quite considerable”

In terms of self-reported misuse, another survey by Matheson et al. sent out to 1,000 randomly selected individuals aged 18 years and over in 2016, found that analgesics (with and without codeine) were the most frequently misused OTC products[12]

. Of those respondents who said they had developed dependence on an OTC medicine, most said they were rarely or never questioned by pharmacy staff about their medicine needs or health condition.

The research revealed that there is public awareness that OTC medicines are associated with risks but it highlighted the need for improved pharmacovigilance of OTC medicines and for healthcare providers to be aware of the potential for misuse, abuse and dependence, particularly in patients with long-term illnesses.

People are self-medicating for chronic pain and don’t appreciate that the products that they’re taking are potentially addictive

“Chronic pain is an issue,” says Matheson.

“People are self-medicating for chronic pain generally and just don’t appreciate that the products that they’re taking are potentially addictive.”

A further study by the same group, published in 2019, found that analgesics containing codeine were the most common OTC medicine of dependence seen by doctors in specialist substance misuse treatment services[7]

. The study identified a clear need for specific clinical guidelines for the treatment of OTC drug dependence.

Taking the right dose

Despite their addictive potential, it is unclear whether the OTC opioid products available are strong enough to have any therapeutic value.

Ash Soni, president of the RPS, says “My concern is whether the dosages that are included in OTC products are therapeutically effective.”

Stannard agrees that patients will probably not get much benefit from 8mg of codeine and that the best thing for acute pain management is ibuprofen and paracetamol.

If we are going to continue to have OTC codeine-based products they need to be the right ones, for the right reasons, and we need to have the appropriate mechanisms to manage them

Soni says that if products are sub-therapeutic and causing addiction, there would be an argument for removing them from OTC sales. But, he adds, if the products do have therapeutic value, they are useful for pharmacists to have in their armoury, provided use is properly recorded, which is not currently the case.

Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Ash Soni, president of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, says that if OTC codeine-based products are sub-therapeutic and causing addiction, there would be an argument for removing them from OTC sales

“If we are going to continue to have OTC codeine-based products they need to be the right ones, for the right reasons, and we need to have the appropriate mechanisms to manage them,” he says.

Before the ban in Australia, pharmacies introduced a real-time monitoring system for OTC sales of codeine-containing products, which required customers to show identification in order for their recent codeine purchases to be monitored[1]

.

But Roger Knaggs, a specialist pharmacist in pain management, says that a system such as that would not work currently in the UK: “In the healthcare system in the UK, the IT would let us down.”

Unless the reporting system was established by an organisation such as NHS England or Public Health England, the likelihood of it happening in the UK is “fairly non-existent”, he adds.

Soni says that pharmacists’ read/write access to patient records would help with tracking purchases of OTC opioids.

“If a pharmacist is aware that someone’s buying an OTC product and can see on the record they’ve purchased [a similar product elsewhere] then at least they can have a greater awareness of the decisions being made in another pharmacy,” he explains.

Banning OTC codeine

Matheson stresses that early intervention in the pharmacy would be preferable to a total ban on OTC codeine.

“[Pharmacists] are clearly observing people buying [OTC opioids] and they can tell us which products are being overused, so we think that’s an obvious place to start — to have a care pathway where pharmacists can intervene in an appropriate way.”

She says that pharmacists would need training to do this properly, but adds that they could also link in with specialist addiction services to make sure people get the support they need.

However, she admits that progress on developing a care pathway has been hindered by a lack of funding: “We’ve tried to get funding in Scotland and England, and we haven’t managed to secure that. Unfortunately, getting the money to develop ideas is quite challenging.”

Courtesy of Cathy Stannard

Cathy Stannard, a consultant in complex pain and the pain transformation programme clinical lead for NHS Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group, says that removing OTC codeine products from sale could be “a step too far”

Stannard is ambivalent about removing OTC codeine products altogether, suggesting it could be “a step too far”, particularly if people turn to buying them from other places, such as the internet.

“There may be a middle group [of patients] who get stuck on [OTC codeine] and then get tempted into going onto legitimate sites [to] get more, and then this can ramp up quite quickly,” she says.

Emma Davies, advanced pharmacy practitioner in pain management at Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board, concurs, saying that removing codeine from OTC sales would be counterproductive.

People will always get hold of things from somewhere … removing things from sale is too simplistic

“People will always get hold of things from somewhere [else] or just take another substance — you’re just shifting the problem, removing things from sale is too simplistic,” she says.

But David Juurlink, a pharmacologist and drug safety researcher based in Canada, where it is still possible to get codeine in low-dose tablets without a prescription in most provinces, disagrees.

“It’s really not a sensible policy to have opioids available OTC,” he says.

“The amount of analgesia from eight tablets per day (the maximum dose) is negligible, and people who take more than is recommended can develop ASA [aspirin] or paracetamol toxicity, because it’s combined with them.”

While he acknowledges that making codeine a prescription-only drug would not “magically solve” the opioid crisis, he believes that it could prevent some people from falling into addiction.

Treating pain and dependency

When it comes to treating dependency, McGregor highlights that there are no services available to help people stop taking OTC opioids. She believes that this is where pharmacists and professional pharmacy organisations, such as the RPS, have a role to play.

“Pharmacists need to take the lead,” she says.

Stannard argues that there is a lot of shame and stigma around people who get stuck on OTC opioids. That stigma needs to be dealt with in order to move forward, she explains.

“Because of how they live their lives they think, ‘I can’t be an addict that’s not me’.

We need to look at strategies to take away the shame and generate more awareness

“[We need to look at] strategies to take away the shame and generate more awareness, [for example] saying to people’s families or their partners ‘look out for this, have a conversation’.”

She adds that it is easy to slip into OTC opioid addiction, but that people who are supported to stop taking these medicines do very well. Individuals may also require support in other areas, for example, for psychological and emotional factors that may be playing a part.

Community initiatives, such as social prescribing, and commissioning from arts and cultural organisations, can help patients to deal with the parts of their lives that may have been overshadowed by pain. These initiatives can address worries and concerns associated with chronic pain, such as finances, social isolation, mobility and weight management, says Stannard.

Support for chronic pain, though, is variable across the UK. “One of the problems in the UK is that pain management clinics are often a last resort as opposed to the first [place] someone is directed to when they present,” explains Davies.

“For example, with back pain, they might be given ibuprofen and co-codamol, but then the pain doesn’t go away, their medicines are escalated and they still haven’t seen a specialist.”

“It could be another five years, after they’ve exhausted all surgical options, that they will be sent to a chronic pain service, only for them to be told it’s all around self-management,” she adds.

Davies says that pain management in the UK is currently medicine focused, but pharmacists, as medicines experts, have a huge role to play in educating practitioners and the general public about the rational use of these medicines.

Knaggs has been championing the role of community pharmacy in this area, but says that he has had push-back from community colleagues who say they do not have the time to talk to patients about OTC opioid abuse.

Source: Charlie Milligan

Roger Knaggs, a specialist pharmacist in pain management, has been championing the role of community pharmacy in helping patients understand the rational use of OTC opioids but says that he has had push-back from colleagues who say they do not have the time

But, he adds, pharmacists would only need to take small steps to improve interactions with patients.

“Even if it were very short and simple questions such as ‘so you’ve been taking these for several months, what difference have they made?’ — I don’t think it needs to be any more complicated than that.”

However, a survey carried out by

The Pharmaceutical Journal

in April 2018 indicates that pharmacy teams may need support, backed up by evidence, in order to increase their confidence in the area of pain management. For instance, more than 20% of respondents would recommend co-codamol as a first-line treatment for migraine, which goes against guidelines[13]

.

Government review

Ultimately any decision to further restrict the availability of OTC opioids will depend on the MHRA’s forthcoming review. Both Soni and Stannard are on the agency’s expert working group.

“We’re reviewing the whole category and seeing whether all of the things that are currently in place are appropriate or whether they need changing — whether that’s from an OTC perspective or prescription,” explains Soni.

Whatever the next step for OTC opioids, it will hopefully go some way to ensuring that those addicted to them do not continue to fly below the radar.

- This article was amended on 27 March 2023 to correct Emma Davies’ affiliation

Box 1: Identifying dependence in over-the-counter opioid users

Annamarie McGregor, practice development lead at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in Scotland, says there are four types of opioid user that a pharmacist should look out for when identifying potential dependency:

- Someone who is in chronic pain and has become dependent on painkillers;

- Someone who is in chronic pain and is upset and agitated, and comes across as being dependent when they’re not;

- Someone whose chronic pain has improved but when they are still dependent;

- People who are misusing.

“We need a different approach for each person. We also need to do more to manage acute pain better and use brief interventions … to support people who are dependent,” McGregor says.

The Chabal 5-Point Checklist is used to identify prescription opioid abuse, but is also relevant for over-the-counter abuse, McGregor explains[14]

.

People meeting three or more of the following criteria are considered prescription opioid abusers:

- They have an overwhelming focus on opioid issues;

- There is a pattern of three or more early refills or escalating drug use without acute changes in their medical condition;

- They make multiple telephone calls or visits to request additional opioids or early refills;

- There is a pattern of prescription problems owing to lost, spilled or stolen medicines;

- They acquire supplemental sources of opioids from other providers or illegal sources.

Other questions pharmacists can ask themselves to differentiate between dependence and sub-optimal pain management include:

- What, when and why are they taking opioid-containing medicines?

- Is there undiagnosed neuropathic pain?

- What effect does their pain have on mobility and function?

- What is the pattern of medicines use?

- Have they stopped taking opioids?

- If so, what happened?

- Is the original pain still there?

- Are there any signs of opioid toxicity?

Useful resources

- The Prescription Opioid Misuse Index — this can be used to identify if the person is dependent

- Opioids Aware— a resource for patients and healthcare professionals, to support prescribing of opioids for pain, from The Royal College of Anaesthetists’ Faculty of Pain Medicine

Box 2: Opioid products available over the counter

There are several codeine-containing analgesic compound products available over the counter in the UK, each containing varying amounts of codeine:

Almus ibuprofen and codeine (Almus) — 12.8mg codeine phosphate hemihydrate, 200mg ibuprofen;

CODIS 500 (RB) — 8mg codeine phosphate, 500mg aspirin;

Nurofen Plus (RB) — 12.8mg codeine phosphate, 200mg ibuprofen;

Paracodol tablets (Bayer) — 8mg codeine phosphate, 500mg paracetamol;

Paramol (SSL International) — 7.46mg dihydrocodeine tartrate, 500mg paracetamol;

Solpadeine max soluble tablets (Omega Pharma) — 12.8mg codeine phosphate hemihydrate, 500mg paracetamol, 30mg caffeine;

Solpadeine max tablets (Omega Pharma) — 12.8mg codeine phosphate hemihydrate, 500mg paracetamol;

Solpadeine plus capsules, tablets and soluble tablets (Omega Pharma) — 8mg codeine phosphate hemihydrate, 500mg paracetamol, 30mg caffeine;

Syndol headache relief tablets (Sanofi) — 8mg codeine phosphate, 500mg paracetamol, 30mg caffeine;

Ultramol Soluble (Sanofi) — 8mg codeine phosphate, 500mg paracetamol, 30mg caffeine;

Veganin (Omega Pharma) — 8mg codeine phosphate, 500mg paracetamol, 30mg caffeine.

Migraleve Complete (McNeil Products):

- Migraleve Pink — 8mg codeine phosphate, 500mg paracetamol, 6.25mg buclizine hydrochloride (also sold separately);

- Migraleve Yellow — 8mg codeine phosphate, 500mg paracetamol.

Own-brand codeine-containing analgesic products are also available.

Source: National Pharmacy Association[15]

References

[1] Kirby T. The end of over-the-counter codeine in Australia. Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5(5):395. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30146-9

[2] Roxburgh A, Hall W, Burns L et al. Trends and characteristics of accidental and intentional codeine overdose deaths in Australia. Med J Aust 2015;203(7):299. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00183

[3] Klein A. Australia bans non-prescription codeine to fight opioid crisis. 2017. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2116813-australia-bans-non-prescription-codeine-to-fight-opioid-crisis/ (accessed June 2019)

[4] Meyerowitz-Katz G. Making codeine prescription-only was right. Where do we go from here? The Guardian. 14 February 2018. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/14/making-codeine-prescription-only-was-right-where-do-we-go-from-here (accessed June 2019)

[5] Australian Department of Health & Therapeutic Goods Administration. Significant decrease in the amount of codeine supplied to Australians. 2019. Available at: https://www.tga.gov.au/media-release/significant-decrease-amount-codeine-supplied-australians (accessed June 2019)

[6] Wickware C. MHRA expert working group launches review of opioid use. Pharm J 2019. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2019.20206169

[7] Fingleton N, Duncan E, Watson M & Matheson C. Specialist clinicians’ management of dependence on non-prescription medicines and barriers to treatment provision: an exploratory mixed methods study using behavioural therapy. Pharmacy 2019;7(1):25. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7010025

[8] Cooper R. ‘I can’t be an addict. I am.’ Over-the-counter medicine abuse: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002913. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002913

[9] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Over-the-counter painkillers containing codeine or dihydrocodeine. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/over-the-counter-painkillers-containing-codeine-or-dihydrocodeine (accessed June 2019)

[10] Wright J, Bond C, Robertson H & Matheson C. Changes in over-the-counter drug misuse over 20 years: perceptions from Scottish pharmacists. J Pub Health (Oxf) 2016;38(4):793–799. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv169

[11] Connelly C. Breakdown of the OTC medicines market in Britain. Pharm J 2018;7913(300):292–293. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2018.20204913

[12] Fingleton N, Watson M, Duncan E & Matheson C. Non-prescription medicine misuse, abuse and dependence: a cross-sectional survey of the UK general population. J Pub Health (Oxf) 2016;38(4):722–730. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv204

[13] Robinson J. Pharmacists should do more to help patients with OTC analgesics, experts say. Pharm J 2019. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2019.20205474

[14] Chabal C, Erjavec M, Jacobson L et al. Prescription opiate abuse in chronic pain patients: clinical criteria, incidence, and predictors. Clin J Pain 1997;13(2):150–155. PMID: 9186022

[15] National Pharmacy Association. Counter Intelligence Plus: The training guide for pharmacy assistants. London: Communications International Group; 2019:B2–B12