Courtesy of Lorraine Jones, Science Photo Library, Shutterstock.com

An ageing population poses challenges for both current and future healthcare systems, with more people suffering from long-term conditions and co-morbidities[1]

, including foot conditions. However, it is important to note that foot conditions can occur among patients of any age and for a number of reasons (e.g. participation in sports, hygiene and lifestyle). See our infographic for further information.

Reviews of international foot surveys conducted in the UK and worldwide demonstrate that 20–78% of people suffer from corns, calluses and bunions; 20–49% have lesser toe deformities; and 28–56% have conditions affecting their toenails[2]

.

Further systematic reviews found that one in five people in middle and old age suffered from foot and/or ankle pain[3]

. The toes and forefoot are the most commonly affected sites, with pain experienced more frequently in females than males[3]

. Two-thirds of patients report that their daily life was affected because of this pain, indicating the high impact that foot conditions have on patients[3]

.

Owing to the large number of the general population suffering from foot problems and the increasing burden of an ageing population, this article will describe the important role of pharmacists and the pharmacy team in engaging patients in preventative care; advising on the correct self-management of common foot-related conditions; and the appropriate referral of patients to allied health professionals for additional treatment and advice.

Fungal foot infections

The most commonly encountered foot infections are fungal and include tinea pedis and onychomycosis. Around 34% of the European population is thought to have a fungal foot infection (FFI) (either tinea pedis, onychomycosis or both)[4],[5],[6],[7]

.

Regional variation shows rates of FFIs are generally higher in Northern European regions — probably because of longer winters, where occlusive footwear is worn for longer periods of the year, which promotes fungal growth. Infection rates are also higher in males and increase with age[7]

.

FFIs can have an impact on quality of life, particularly when the infection affects the nails[4],[5],[8]

. Fungal nails become unsightly, thickened and crumbly, and may become painful within an enclosed shoe owing to pressure from the upper onto the nails. Many people with fungal nails will not wear open-toed sandals because they are embarrassed. In addition, the skin affected by tinea may be itchy, uncomfortable, and at an increased risk of bacterial infection in areas of excoriation. Cycles of reinfection from nail and skin also occur if the infection is not resolved.

Onychomycosis

Up to 50% of fungal diseases of the nail can be attributed to onychomycosis[7]

, which affects around 2–8% of adults in the western world[9]

.

Two dermatophytes (fungi that require keratin for growth), Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, account for more than 90% of onychomycoses[7]

. However, some yeasts and moulds also cause these infections.

Onychomycosis is more common in men than women and there is a correlation between increasing age and infection[3]

. Fungi spreading from fungal skin infections, such as athlete’s foot (known as ‘dermatophyte fungi’) are the cause of most fungal nail infections[8]

.

Signs and symptoms

When fungi infect a nail, they usually start at its free edge, and then spread down the side of the nail towards the base of the cuticle. Eventually the whole nail may be involved. The infected areas turn white, black, green or yellowish, and become thick and friable. Less commonly, there may be superficial white patches on the nail surface. Infected nails may separate from the nail bed (also known as onycholysis).

Studies have identified that the large toenails are the most frequently affected, and patients have, on average, three affected toes[9]

.

Nails and skin, when healthy and intact, are barriers to infection. However, when either skin or nails are weakened, they become more vulnerable to infection. Trauma to the toe nails is a threat to nail integrity, while also making them more vulnerable to fungal infection[10]

.

Fungal nails

Source: Courtesy of Lorraine Jones and Nicholas Masucci

Fungal nails become unsightly, thickened and crumbly, and may become painful within an enclosed shoe owing to pressure from the upper onto the nails.

Treatments

Pharmacists, pharmacy teams and healthcare professionals can recommend over-the-counter (OTC) treatments to patients, which should be used early in the infection.

Topical treatments used most often include antifungal nail lacquers, such as amorolfine 5% nail lacquer and tioconazole 28% nail solution, or nail-softening kits.

Box 1 lists some important considerations pharmacists and pharmacy teams should take into account before recommending antifungal nail lacquers.

Box 1: Important considerations for antifungal nail lacquers

- Topical paint does not reach the deeper layers of the nail and is not as effective as oral medication;

- Topical treatments work well in conjunction with oral treatments;

- Over-the-counter (OTC) treatments rarely work when the whole nail is affected;

- Treatment requires good compliance as it can continue for 6–12 months.

Fungal nails are often dystrophic and thickened, therefore, reduction of the diseased part of the nail plate can often improve effectiveness of antifungal treatments.

The decision to treat toenail onychomycosis with a systemic agent should be considered carefully[11]

because oral medications come with some side effects and risks, and may not be suitable for everyone. Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should refer patients to a podiatrist or GP for antifungal tablets, which include griseofulvin, terbinafine and itraconazole. The latter two are more effective than griseofulvin[11]

.

Current UK guidelines from the British Association of Dermatologists[12]

and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[13]

recommend that any patient with suspected onychomycosis should have laboratory confirmation before treatment, particularly if oral antifungal therapy is being considered.

Some newer, non-oral onychomycosis treatments are available and involve making tiny holes in the nail plate, allowing controlled micro penetration of the topical treatment to reach the nail bed in much higher concentration levels than otherwise possible. Results are usually visible within two to eight weeks[14]

.

Lifestyle factors

Co-morbidities such as diabetes, AIDS and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) may be independent predictors of onychomycosis[7]

, therefore, pharmacy teams should be aware of patients with these conditions and offer them additional counselling about foot health, foot hygiene (see Box 2) and FFIs.

Box 2: Foot hygiene routine

- Daily foot care

- Wash and thoroughly dry feet every day, including between the toes;

- Wear clean socks daily;

- Rotate shoes — do not wear the same pair two days in a row. Give shoes time to dry out, especially if the patient is active or perspires heavily.

- Toenail care

- Trim toenails regularly (at least every two weeks). Cut them straight across, not on a curve, and file down sharp edges using an emery board;

- Use clean nail clippers or scissors. Sanitise them periodically by immersing them in alcohol;

- If a patient has visual or mobility problems, or diabetes and/or neuropathy (loss of sensation in the feet), peripheral vascular disease or other circulatory issues in the feet and legs, they should be advised to visit a foot healthcare professional and, where appropriate, ask family or friends to help file their nails.

- Daily foot inspection

- Check the tops and bottoms of feet, as well as toes, between toes and toenails;

- For any abrasion, area of redness or unusual sensation, tenderness or pain that patients do not know the cause of, or if pain does not go away on its own, patients should be referred to a physician or foot specialist.

Patients with onychomycosis should be advised to avoid using any nail polish, and to treat athlete’s foot immediately (see below).

When to refer

Patients with thickened, brittle or dystrophic nails, paronychia (an infection of the skin around the nails), those resistant to topical treatments and at-risk patients (such as those with immunosuppression, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease or neuropathy) should be referred to a podiatrist or GP.

Athlete’s foot

Athlete’s foot, also known as tinea pedis, is a cutaneous fungal infection caused by dermatophyte infection, which thrives in warm, humid conditions. Athlete’s foot affects around 15% of the population[15]

, and males are more often affected than females.

Over 70% of the population will experience an episode of athlete’s foot infection during their lifetime[16]

, with prevalence increasing with age, most frequent infections occur in adults aged 31–60 years[17],[18]

.

Signs and symptoms

Itching, scaling and redness are the main features of athlete’s foot[19]

and, in severe cases, vesicular eruptions can also be present[20]

.

Skin between the toes may appear macerated, the soles of the feet may become dry and flaky (‘moccasin distribution’), which can be a significant risk factor for acute bacterial cellulitis of the leg[21]

.

The main causative agents are dermatophytes. The most common fungi responsible are Trichophyton rubrum and, to a lesser extent, T. Mentagrophytes var.interdigitale, which between them accounted for around 90% of fungal foot infections in the UK in 2005[11]

.

Athlete’s foot

Source: Shutterstock.com

Athlete’s foot is a cutaneous fungal infection. The affected skin may be itchy, red, scaly, dry, cracked or blistered.

Treatment

Primary treatment usually involves a topical antifungal agent. The most important aspect of treatment is to treat the whole foot and both feet. Creams or sprays are usually preferable as they are associated with better outcomes. Oral antifungal therapy, such as terbinafine, is reserved for people with chronic or extensive disease, or where application of a topical agent is not feasible[22]

.

For itchy, inflamed skin with the presence of vesicles, the use of potassium permanganate foot baths is a useful adjunct to treatment.

While fungi cause the main infection, a yeast infection may also develop, therefore, when the usual OTC tinea treatments do not work, switching to a dual action treatment may be successful.

Lifestyle advice

Fungi love warm, dark, damp conditions. Pharmacists, pharmacy teams and healthcare professionals should counsel patients on good foot hygiene, and recommend that patients alternate their footwear and wear clean socks daily (see Box 2). Patients should be reminded that separate towels should be used for their feet as the infection can spread to other parts of the body[22]

. Feet should be dried well, especially interdigitally, and any footwear used during sports activity or exercise should be allowed to fully dry out between each wear.

When to refer

Patients should be referred to their GP if there has been no improvement after one week of treatment. However, depending on the product used, treatments can sometimes take longer than one week to work.

Verrucae and warts

Detailed information on various types of warts, their presentation and treatment can be found in a previous article

[23]

.

Verrucae are plantar warts, located on the sole or toes of the foot and are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of keratinocytes, the most dominant cell type in the epidermis, which results in development of epidermal thickening and hyperkeratinisation[24],[25]

. HPV infection is acquired from direct contact, which may be person-to-person or from the environment (e.g. showers and swimming pools; skin penetration increases if the skin is broken or wet)[26]

.

Around half of verrucae in children disappear on their own within a year, and two-thirds resolve within two years, but they can take many years to resolve in adults (see Infographic).

Signs and symptoms

Often painful when they first start, verrucae have an encapsulated appearance and skin striations appear to punctate areas of haemorrhage (black dots).

Other signs and symptoms of warts include:

- A singular or clustered appearance (sometimes forming a mosaic ranging from 1mm to over 1cm in diameter);

- Raised skin growth with a hard, uneven surface. Cauliflower-like in appearance. Some may appear to lie flat on the skin — these plane warts tend to be less painful;

- Pain or flattened appearance, especially on weight-bearing areas, due to the pressure over them;

- Black dots, which are blood vessels. These may bleed if scratched;

- Deformed and loose nails, caused by their occurrence beneath the free edge of the nail;

- Itching.

Verrucae

Source: Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

Verrucae are plantar warts, located on the sole or toes of the foot. They are white, often with a black dot in the centre, and tend to be flat rather than raised.

Treatment

Treatment is recommended to lessen symptoms (which may include pain), decrease duration and reduce transmission[27]

. Treatment options include salicylic acid, often in combination with lactic acid, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde and cryotherapy (see below). See previous Learning article for more information on treatment of patients who may be immunocompromised[23]

.

Pharmacists and pharmacy teams should advise patients to read the relevant instructions and use a product for only a week or two. However, some patients may require continuous application for 2–3 months, sometimes longer. In the authors’ experience, compliance can be a problem with topical self-treatment, so appropriate counselling may be required.

Salicylic acid based OTC products are most commonly used and may take a few months of consistent application[28]

. Evidence suggests that salicylic acid is the most effective OTC treatment[29]

; however, these treatments may irritate the patient’s skin and do not always work.

Topical salicylic acid (15–50% w/w), applied to the wart daily for 12 weeks, is the treatment of choice for adults and older children. Its exact mechanism of action is not known but it acts as a keratolytic, resulting in the removal of epidermal cells infected by HPV[29]

.

Salicylic acid preparations are available in a range of treatments, including gels, paints, plasters, solutions and ointments, and they often also include lactic acid. Gel treatments may also contain colophony, which may cause an allergic reaction in some patients[30]

.

Salicylic acid should not be applied to warts on the face, intertriginous areas (where skin rubs together, such as the axilla), anogenital warts, moles or birthmarks, warts with hair or red edges, or to open lesions or broken skin[24]

. When using salicylic acid, patients should be advised to protect the surrounding skin to avoid irritation; this can be done by coating the area with soft paraffin or by using plasters.

Salicylic acid is not recommended for use in patients with diabetes, as these patients often have peripheral neuropathy and poor circulation, leading to poor wound healing[24]

. The NHS states that salicylic acid can be used to treat warts in pregnancy but only on a small area for a limited period of time.

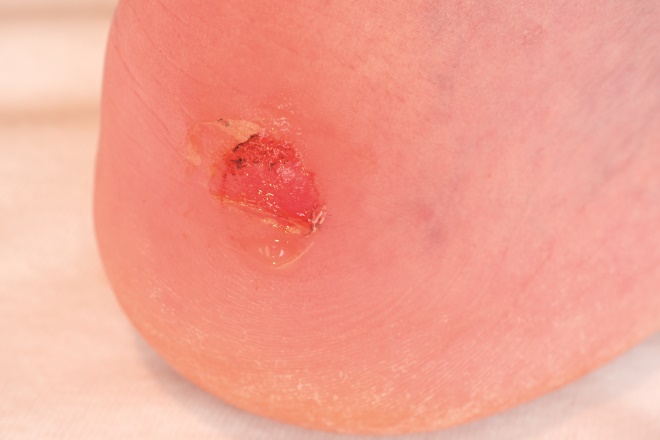

Verruca with maceration from salicylic acid

Source: Courtesy of Lorraine Jones and Nicholas Masucci

Salicylic acid based over-the-counter products are most commonly used to treat verrucae. Salicylic acid is not recommended for use in patients with diabetes.

Formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde are applied in a similar way to salicylic acid. Glutaraldehyde can stain the skin brown, and should be discontinued if skin irritation is severe.

Patients using OTC treatments can be advised to debride the surface of the wart gently with a file (e.g. emery board) or pumice stone once weekly. However, this should be done carefully as there is a risk of further spread of the infectious material. Patients should also soak the wart for five minutes before treatment to soften it.

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen can be offered by trained clinicians, and can be suitable for adults and older children who are able to tolerate it under local anaesthetic. It rapid cools the cells, causing ice crystals to form on the cell surface, disrupting membranes. When thawing occurs, extracellular fluid becomes hypertonic, with the rapid flow of water into cells causing cell death[31]

. There are also some OTC treatments available that are based on cryotherapy.

Advice on how to assess skin lesions can be found in a previous article[23]

.

Other treatments, such as bleomycin and imiquimod cream, are available on prescription and have an increased success rate, but there can be associated sensitisation[32],[33]

.

Lifestyle advice

Cover verrucae and warts with an adhesive bandage while swimming. Wear flip-flops when using communal showers, and do not share towels[24]

.

When to refer

Patients who are resistant to OTC treatments and at-risk patients (e.g. patients with diabetes, presence of neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, who are immunosuppressed, have poor systemic health, pain on walking, inflammation, and patients for whom self-treatment is unsuccessful) should all be referred to their GP or a podiatrist for further care.

Suspicious lesions should be referred to specialists.

Blisters and bullae

A blister may form when the skin has been damaged by friction, heat, cold or chemical exposure. Fluid collects between the epidermis and the layers below, and protects from further damage, allowing the skin below it to heal.

Friction is the most usual cause of a blister on the feet, mainly after walking long distances or by wearing poorly fitting shoes[34]

.

Blisters form more easily on moist skin than on dry or soaked skin[35]

, and are more common in warm conditions.

Blisters and bullae

Source: Shutterstock.com

Blisters are small pockets of fluid that usually form in the upper layers of skin after it has been damaged. This protects the tissue from further damage and allows it to heal.

Treatment

Micropore tape can be used as an excellent preventative measure. Other available OTC products include blister plasters, and antiperspirants can be recommended to patients experiencing excessive sweating. Socks that wick sweat may also be useful.

Patients should be advised not to burst blisters and that they can be covered with plaster or gauze if additional protection or cushioning is required.

Lifestyle advice

Pharmacists, pharmacy teams and healthcare professionals should advise patients to wear well-fitted footwear. Footwear should ideally be laced so that the foot is held securely when walking down- or uphill. Use of surgical spirit interdigitally will help keep the skin dry, reducing potential for blistering.

When to refer

Patients with signs of infection, those experiencing pain, or those with large blisters should be referred to their nurse or GP.

Ingrown toenails

A common condition causing pain and disability, onychocryptosis is caused by the actual penetration of flesh by a sliver of nail.

Most commonly found in the big toe, patients are usually male, aged between 15 and 40 years[36]

. Cases of ingrown nail have a reported male-to-female ratio of 3:1[36]

.

Trauma appears to play a major role[37]

, but common causes also include poor nail-cutting, chemotherapy, moist skin, toe deformities, abnormal nail growth and fleshy toes.

Signs and symptoms

Patients may experience pain, redness, inflammation and infection as a result of nails growing into the nailbed. Exudate and hypergranulation tissue may also be present[38]

.

Differential diagnosis may also include subungual exostosis, periungual fibroma, amelanotic melanoma, glomus tumours and corn in sulci.

Ingrown toenails

Source: Courtesy of Lorraine Jones and Nicholas Masucci

An ingrown toenail develops when the sides of the toenail grow into the surrounding skin. Patients may experience pain, redness, inflammation and infection.

Lifestyle advice

Pharmacists, pharmacy teams and healthcare professionals should advise patients to wear well-fitting shoes, cut nails straight across and promote good foot hygiene practices (see Box 2).

Treatment

At the initial signs of an ingrown toenail, before the nail pierces the skin, patients can use a nail clip and spray that helps to train the nail to grow straight. However, once the nail has pierced the skin, effective treatment can involve either partial or total nail removal and, if the condition is recurrent, either ablation or excision of the nail bed may be required.

When to refer

Pharmacists, pharmacy teams and healthcare professionals should refer patients who are in severe pain, have infection, swelling, exudate or there is bleeding from the wound[38]

, if there is a recurrent problem requiring repeated antibiotics, and also at-risk patients. Referral to a podiatrist should be made if the patient requires a nail to be removed. If neglected, paronychia may occur or spread and lead to osteomyelitis, systemic infection, sepsis or amputation.

Bunions and bursitis

Hallux valgus (HV), often referred to as a bunion, is a common and progressive deformity of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. A 2008 UK study reported a prevalence of 28.4% in adults[39]

, with females affected three times more than males.

HV is a condition more common in the elderly. Around 23% of adults aged 18 to 65 years have HV compared with 36% of those aged over 65[40]

.

Signs and symptoms

The big toe deviates laterally and the first metatarsal moves medially. It is the head of the first metatarsal that gives rise to the bunion prominence. The overlying soft tissue, owing to footwear pressure, can become inflamed and swollen, and can often develop painful bursitis.

HV deteriorates over time and can lead to severe deformity in early middle age. It is associated with bursitis, functional disability, foot pain, impaired gait patterns, poor balance, and falls in older adults[40]

. The pain is due to footwear pressure over the bunion prominence, and to the abnormal alignment at the metatarsophalangeal joint, resulting in inflammation of the joint and pain. This can also lead to excessive lateral loading of the metatarsal heads and associated lesser toe deformities.

Most shoes do not accommodate the resulting protrusion and put pressure on the misaligned joint. Eventually, the bursa (a fluid-filled sac that surrounds and cushions the joint) becomes inflamed, and the entire joint becomes stiff and painful.

Bunions / bursa

Source: Courtesy of Lorraine Jones and Nicholas Masucci

A bunion is a deformity of the big toe, where the big toe excessively angles towards the second toe and leads to a bony lump on the side of the foot. This can also form a large sac of fluid, known as a bursa.

Treatments

Conservative measures may help relieve symptoms, although there is no evidence they can correct the underlying deformity.

Exercises, such as calf stretches to counteract the shortening of the calf, can help to keep feet supple.

Orthoses can help control the alignment of the foot and help accommodate deformity, reduce pain and help increase mobility. Shoe alterations or night splints, which hold toes straight during sleep, can help to slow the progression of bunions in children. Toe alignment splints will not correct bunions but can give temporary relief from discomfort.

Padding, painkillers and ice packs might also help relieve pain.

Bunion shields may help reduce friction and a degree of pressure from the enlarged joint. Orthoses do not prevent the progression of the deformity but may be helpful for those with joint pain.

If conservative management fails, there is surgical correction. Procedures now make use of cuts in bone, which are intrinsically stable, and many internal fixation devices are available to maintain alignment leading to early mobilisation. This is often carried out as a day case.

Lifestyle advice

Footwear has a direct impact on foot function and if the footwear does not fit properly, foot function is compromised.

Wearing sensible shoes that fit well is a good preventative measure. For example, a shoe with a strap or lace over the instep holds the foot secure and helps stop it sliding forward. Wider shoes provide toes with room to move and heel height should be no more than 4cm for maximum comfort.

Many patients will need to alter the type of sport or exercise they do, particularly activities that aggravate the joint and cause pain.

When to refer

Patients should be referred when pain becomes debilitating (e.g. ongoing daily discomfort, redness, inflammation), despite conservative treatment.

Corns and calluses

Small circular thickenings of the outer layer of skin develop to protect skin against damage from sheer forces, pressure and other forms of irritation. Corns affect between 13% and 48% of the population (see Infographic).

Women are more predisposed than men owing to choice of footwear and possible presence of toe deformities, such as hammer toes, as a result of more restrictive styles of footwear.

Signs and symptoms

With calluses, the thickening is evenly distributed and often caused by friction, related to foot abnormalities that place unusual stress on parts of the foot during walking, and movement in shoes.

Corns usually develop over bony prominences and are the result of excessive pressure. Corns have a deeper core of callus located over the area of greatest friction or pressure.

They can cause pain and difficulty walking. Some may develop discoloration within the corn or callus, which is caused by a small amount of bleeding into the skin, especially in the presence of toe deformities because it is difficult to find shoes to accommodate these deformities.

Corns and calluses

Source: Shutterstock.com

Corns and calluses are areas of hard, thickened skin that develop when the skin is exposed to excessive pressure or friction. They commonly occur on the feet and can cause pain and difficulty walking.

Treatment

Pharmacists, pharmacy teams and healthcare professionals can advise patients with corns or calluses to remove pressure and apply rehydration cream, corn plasters, silicone toe protectors, pads or salicyclic acid products. As previously stated, salicylic acid treatments should not be used in people with poor circulation or diabetes. The use of cushioning insoles can also be helpful.

When to refer

Patients should be referred if pain is constant and affects walking and daily activities or if the area surrounding the corn or callus is red, warm or swollen. Corns and calluses are symptoms of an underlying problem (e.g. friction from a loose shoe or joint deformities) and may need specialist treatment from a podiatrist to identify and address the problem.

At-risk patients, such as those with vascular conditions, neuropathy, neurological conditions, and patients who are immunosuppressed and diabetic should be referred to specialist nurse clinics, podiatrists or their GPs. Those at risk should never use OTC callus or corn removal products containing salicylic acid because skin breakdown/ulceration can occur.

RB provided financial support in the production of this content. The Pharmaceutical Journal retains full editorial control.

UK/SC/0617/0031h

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Office for National Statistics. Overview of the UK population: March 2017. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/mar2017 (accessed August 2017)

[2] Farndon L, Vernon DW & Parry A. What is the evidence for the continuation of core podiatry services in the NHS: a review of foot surveys. Br J Podiatry 2006;9(3):89–94. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238078167_What_is_the_evidence_for_the_continuation_of_core_podiatry_services_in_the_NHS_A_review_of_foot_surveys (accessed July 2017)

[3] Thomas MJ, Roddy E, Zhang W et al. The population prevalence of foot and ankle pain in middle and old age: a systematic review. Pain 2011;152(12):2870–2880. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.019

[4] Turner R & Testa M. Measuring the impact of onychomycosis on patient quality of life. Qual Life Res 2000;9(1):39–53. PMID: 10981205

[5] Lubeck DP, Patrick DL, McNulty P et al. Quality of life of persons with onychomycosis. Qual Life Res 1993;2(5):341–348. PMID: 8136799

[6] Burzykowski G, Molenberghs D, Abeck E et al. High prevalence of foot diseases in Europe: results of the Achilles project. Mycoses 2003;46(11–12):496–505. doi: 10.1046/j.0933-7407.2003.00933.x

[7] Faergemann J & Baran R. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol 2003;149(Suppl 65):1–4. PMID: 14510968

[8] British Association of Dermatologists. Fungal infections of the nails. 2017. Available at: http://www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=205&itemtype=document (accessed August 2017)

[9] Ameen M. Epidemiology of superficial fungal infections. Clin Dermatol 2010;28(2):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.12.005

[10] Shemer A, Trau H, Davidovici B et al. Onychomycosis: rationalization of topical treatment. Isr Med Assoc J 2008;10(6):415–416. PMID: 18669135

[11] Scher RK, Tavakkol A, Sigurgeirsson B et al. Onychomycosis: diagnosis and definition of cure. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56(6):939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.019

[12] Ameen M, Lear JT, Madan V et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of onychomycosis 2014.Br J Dermatol 2014;171(5):937–58. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13358

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fungal nail infection. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/fungal-nail-infection#!scenario (accessed August 2017)

[14] Menz HB & Lord SR. Foot pain impairs balance and functional ability in community-dwelling older people. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2001;91(5):222–229. PMID: 11359885

[15] Havlickova B, Czaika VA & Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses 2008;51(Suppl 4):2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x

[16] Brooks KE & Bender JF. Tinea pedis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 1996;13(1):31–46. PMID: 8849930

[17] Drakensjö IT & Chryssanthou E. Epidemiology of dermatophyte infections in Stockholm, Sweden: a retrospective study from 2005–2009. Med Mycol 2011;49(5):484–488. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.540045

[18] Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Garlowska E et al. Factors influencing coexistence of toenail onychomycosis with tinea pedis and other dermatomycoses: a survey of 2761 patients. Arch Dermatol 2006;142(10): 1279–1284. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.10.1279

[19] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hygiene-related diseases. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/hygiene/disease/index.html (accessed August 2017)

[20] Martin-Lopez JE. Athlete’s foot. BMJ Best Practice Available at: http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/evidence/background/1712.html (accessed August 2017)

[21] Roujeau JC, Sigurgeirsson B, Korting HC et al. Chronic dermatomycoses of the foot as risk factors for acute bacterial cellulitis of the leg: a case-control study. Dermatology 2004;209(4):301–307. doi: 10.1159/000080853

[22] Andrews MD & Burns M. Common tinea infections in children. Am Fam Physician 2008;77(10):1415–1420. PMID: 18533375

[23] Akram S & Zaman H. Warts and verrucas: assessment and treatment. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2015;294:7867. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2015.20068680

[24] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Warts and verrucae. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Available at:http://cks.nice.org.uk/warts-and-verrucae#!topicsummary (accessed August 2017)

[25] Dinulos JGH. Warts (verrucae vulgaris). Available at: http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/dermatologic-disorders/viral-skin-diseases/warts (accessed August 2017)

[26] Sterling JC. Virus infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N et al. (eds.) Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. 2010;33.1–33.81

[27] NHS choices. Warts and verrucas. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/warts/pages/introduction.aspx?nobeta=true (accessed August 2017)

[28] Kwok CS, Gibbs S, Bennett C et al. Topical treatments for cutaneous warts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD001781. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001781.pub3

[29] Sterling JC, Gibbs S, Haque Hussain SS et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of cutaneous warts. Br J Dermatol 171(4):696–712. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13310

[30] BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. British National Formulary 72. September 2016–March 2017. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society. ISBN: 978 0 85711 273 6

[31] Nguygen NV & Burkhart CG. Cryosurgical treatment of warts: dimethyl ether and propane versus liquid nitrogen — case report and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol 2011;10(10):1174–1176. PMID: 21968668

[32] Dyall-Smith D. Bleomycin and the skin. Available at: https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/bleomycin (accessed August 2017)

[33] Drugs.com. Imiquimod topical side effects. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/sfx/imiquimod-topical-side-effects.html (accessed August 2017)

[34] Naylor PFD. Experimental friction blisters. Br J Dermatol 1995;67(10):327–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1955.tb12657.x

[35] Carlson JM. The friction factor. Orthokinetic Rev 2001;1(7):1–3.

[36] Park DH. The management of ingrowing toenails. BMJ 2012;344:e2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2089

[37] Kline A. Onychocryptosis: a simple classification system. Foot & Ankle 2008;1(5):6. doi: 10.3827/faoj.2008.0105.0006

[38] NHS choices. Ingrown toenail. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/ingrown-toenail/Pages/Introduction.aspx (accessed August 2017)

[39] Roddy E, Zhang W & Doherty M. Prevalence and associations of hallux valgus in a primary care population. Arthritis Care & Res 2008;59(6):857–862. doi: 10.1002/art.23709

[40] Nix S, Smith M & Vicenzino B. Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res 2010;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-3-21