BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

Aphasia is a disorder caused by damage to the portions of the brain responsible for understanding and using language; it has been defined as the loss or impairment of the power to use or comprehend words, usually resulting from brain damage[1]

. The term is sometimes used interchangeably with dysphasia, which is more commonly used in Europe.

More than 350,000 people are thought to have aphasia in the UK, and around a third of people who suffer a stroke will experience the condition[2]

. The left-hand side of the brain is most commonly affected, and the damage can occur suddenly — often following a stroke or head injury — but may also develop slowly as the result of a brain tumour, progressive neurological disease, dementia or drug misuse. After a stroke, old age, high levels of disability and a high severity of stroke are risk factors for developing aphasia[3]

.

While improvements can be observed in the first year of recovery following a stroke, greater aphasia severity is associated with poorer recovery. Around half of people affected will have long-term aphasia, which should be viewed as a life-changing condition[3]

.

This article will describe the two main types of aphasia and outline methods of communication that pharmacists and healthcare professionals may use when consulting with people with the condition about their medicines.

Types of aphasia

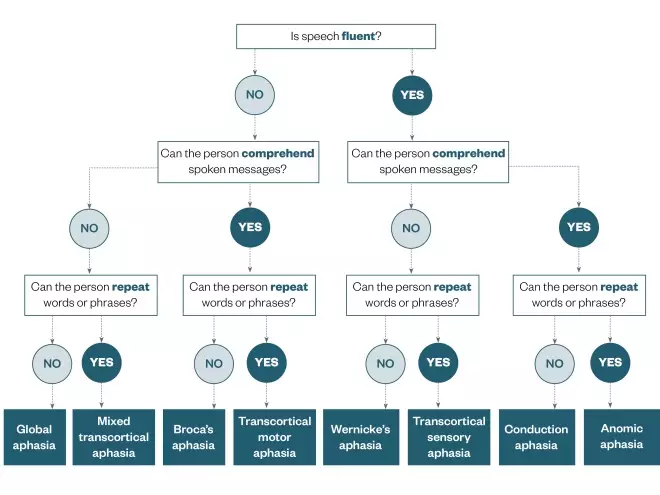

Different types or patterns of aphasia correspond to the location of the brain injury. There are two broad categories and more than eight specific types of aphasia (see Figure 1). It is important for pharmacists and healthcare professionals to understand the two categories of aphasia, known as expressive and receptive aphasia. Aphasia can affect single and multiple communication methods, as well as comprehension and expression, including writing, reading, drawing and gesticulating[3]

.

Figure 1: Types of aphasia

Source: The Pharmaceutical Journal

Flow chart showing the different types of aphasia and how they are identified

Broca’s aphasia is the most generally recognised form of aphasia, also known as expressive or non-fluent aphasia[4]. People with Broca’s aphasia maintain good comprehension of spoken language, but with a disturbance in or loss of speech. This may manifest as a person saying “walk, dog”, meaning “I will take the dog for a walk”.

Wernicke’s aphasia is characterised by a severe deficit in auditory comprehension, with fluent, spontaneous, but incoherent speech being present[4]

. However, people with Wernicke’s aphasia are usually unaware that their speech is unintelligible. An example would be where a patient calls a fork a “gleeb”[5]

.

How aphasia affects communication

The impact of aphasia on communication, and thus relationships, ranges from mild to profound. Aphasia can affect all aspects of communication and can manifest in a number of ways (see Box 1)[3]

. People with aphasia, while being able to think clearly, may have difficulty receiving and transmitting information (messages ‘in’ and ‘out’); however, it is important to remember that no two people are alike with respect to severity, personality, or former speech and language skills.

Aphasia will have an impact on the individual’s ability to communicate their wants and needs, as well as change their ability to undertake and participate in everyday activities. Aphasia can significantly reduce a person’s autonomy, social interactions, educational activities and independence. Therefore, it is not surprising that the emotional wellbeing of people with aphasia is negatively affected, often causing stress on relationships and depression[3]

.

Box 1: Communication challenges for people with aphasia

- Speaking (expressive aphasia);

- Reading;

- Writing;

- Understanding (receptive aphasia);

- Using numbers;

- Dealing with money;

- Telling the time.

A person with expressive aphasia may only be able to say a few words or very short sentences. Their words may be jumbled and they may end up saying a different word to the one they wanted. Often, they have trouble saying what they are thinking and difficulty writing words and sentences. People with expressive aphasia may be able to understand most of what others are saying, but it is often easier for them to understand family and friends, or when they are in a quiet place. It may be harder for them to understand others when there are a lot of people talking or if the environment is noisy, for example, in a ward or community pharmacy[6]

.

A person with receptive aphasia may have an auditory comprehension problem, and therefore experience difficulty understanding what others are saying. They are often unaware that what they are saying is not correct or does not make sense, even though they speak fluently. In addition, they can have problems understanding what they read[6]

.

Sometimes aphasia may be confused with apraxia and dysarthria. These are both speech problems rather than language problems. People with apraxia have slow, laboured speech and struggle to say the sounds or words (for example, instead of “coffee”, saying “bobee”). People with dysarthria may have slurred, soft speech that is hard to hear[6]

.

Role of speech and language therapists in supporting people with aphasia

Speech and language therapists (SLTs) play a unique role in identifying and assessing people with aphasia. In hospital and community settings, SLTs review patients to identify levels of comprehension, expression and other retained communication abilities. They have a key role in educating and training people living with aphasia and their carers, as well as health, education and social care staff, to optimise patient outcomes. The aim of supporting a person living with aphasia is to improve their capacity to communicate by focusing on the use of their remaining language abilities, restoring these as much as possible, while learning alternative communication methods. For SLTs, individual therapy focuses on the specific needs of the person, while group therapy facilitates the opportunity to use these new communication skills in a group setting. Box 2 describes therapies undertaken by SLTs.

Box 2: Communication support provided by speech and language therapists

Speech and language therapists (SLTs) use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), which includes any communication system that supplements or replaces speech, to help people living with aphasia better communicate orally. This involves both ‘low-tech’ methods, such as drawing, writing and using communication books, and ‘high-tech’ tools, such as computerised voice output communication aids. The objective of AAC is to maximise the person’s communicative functions in areas of life that they have identified as a priority[3]

.

Role of pharmacy staff in supporting people with aphasia

Standard provision of medicines-related information supplied with drugs, and through pharmacy staff, includes written information (such as patient information leaflets and instructions on medication containers), as well as verbal instructions (including explanation of how and when to take medicines, what they are for and any side effects). Pharmacy staff in hospital and community settings may also respond to a patient’s general questions, queries and concerns about medicines. However, if a patient has aphasia, standard methods are unlikely to yield safe, effective communication to optimise medicines use.

People living with aphasia are still competent (have sufficient capacity, ability or authority), unless there is evidence to the contrary, to take part in conversations about their treatment. They will often know what they want to say and ask, but have difficulty doing so. This may be frustrating for healthcare professionals, but it is even more frustrating for people living with the condition.

Consultations with people with aphasia

The proposed process outlined below was developed by London North West Healthcare NHS Trust to support safe, effective, person-centred communication with people who have aphasia.

Step 1: Before undertaking any patient consultation

Speak to people who know the patient well and, where possible, engage help from SLTs to determine the current level of aphasia. Schedule a consultation where you can have support of a relative, carer or advocate (with patient permission), or a nurse or SLT. Each patient will have their own needs and preferences, so think about appropriateness of: pen and paper, using drawings and diagrams, providing written information and listing key words.

It is important to make sure you have the patient’s attention before starting the consultation, and that all background noise is eliminated. This may be challenging in community and hospital settings, and requires thought and preparation. Unless the person with aphasia has indicated otherwise, voices should be pitched at a normal level.

Step 2: During the consultation

Communication should be kept simple, with sentence structures simplified and rate of speech reduced. Closed questions can be used throughout the consultation to check the person’s understanding; they can be helped by allowing a choice from keywords or props, such as pictures or medicines bottles and boxes. Messages should be given simply, one at a time, and then recapped to check understanding before continuing. East and South East England Specialist Pharmacy Services has developed a range of resources to be used during anticoagulation consultations with people with aphasia, and similar communication principles have the potential to be adopted for other specialist areas[7]

.

Sufficient time should be allowed for the consultation, to minimise frustration. During the consultation, healthcare professionals should remain comfortable with silence and wait for the patient to answer. It is very important not to attempt to finish their sentences.

It can be helpful to keep a record of the conversation — if either party becomes stuck, acknowledge this, recap where you are at, and decide together how to move forward. Provide the patient with options (using closed questions, if required).

As consultations are often limited in time, and perhaps limited by ability to engage, it is important to provide the person, and any family members and carers, with a chance to prepare questions. It is a good idea to find out beforehand what they want to know and provide key safety information in a variety of ways. Box 3 provides suggestions of questions that people with aphasia may wish to consider, working with the SLT. This form can be given out before the consultation and the completed form can be used by the pharmacist during the consultation. Additional information and guidance is available from the Aphasia Alliance.

Box 3: Questions that patients may want answered in a medicines-related consultation with a pharmacist

Healthcare professionals, including speech and language therapists (SLTs), can ask patients questions about their medicines (in the form of a pro forma) to determine what information pharmacists should focus on during consultations relating to medicines. Patients could be asked if they would like information relating to:

- What is the medicine for?

- I don’t want this medicine, so what can I do instead?

- What do I need to know about the medicine?

- When should I take the medicine?

- How should I take the medicine?

- How long should I take the medicine for?

- What can I do to make the medicine work well?

- I have a lot of medicines to take, so is it OK to take all of the medicines together?

- What if I miss a dose of my new medicine?

- Where can I get more information?

- Is there any other information you would like about your medicine?

Source: Nina Barnett & Sunaina Kaher 2014. [8]

To engage effectively and optimise education with people who have aphasia, pharmacy staff should prepare in advance and allocate enough time for the consultation. Using their knowledge of the type of aphasia, pharmacy staff can utilise communication tools (see Box 4 and useful resources section) to improve safety, efficacy and the patient experience for people with aphasia.

Box 4: Communication tips to optimise communication with a person who has aphasia

- Check that they understand what you are talking about;

- Encourage them to use gestures, writing and drawing to make their meaning clear;

- Keep a pen and paper close by;

- Spend as much time as possible together;

- Encourage the patient to contribute;

- If they get tired, give them some time to rest;

- Relax, be patient and hopeful.

Useful resources

Aphasia-friendly medicines information have been developed by the Medicines Use and Safety Team, NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service, working with consultant pharmacists in anticoagulation and speech and language therapists (SLTs). These resources are designed to support all healthcare professionals who communicate with people with aphasia who have been prescribed oral anticoagulants, and patients who have aphasia or reduced cognition. The resources are free to download. Specialist Pharmacy Service — consultations about oral anticoagulants for patients with aphasia

Other resources

- Beyond aphasia; therapies for living with communication disability

- Stroke.org Accessible Information Guidelines

- The Stroke and Aphasia Handbook 2008 (Book)

Create your own resources

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online. Definition of Aphasia. Available at: www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aphasia (accessed February 2018)

[2] Stroke Association. Aphasia and its effects. Available at: www.stroke.org.uk/what-is-stroke/what-is-aphasia/aphasia-and-its-effects (accessed February 2018)

[3] Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists. Resource manual for commissioning and planning services for speech, language and communication needs. Aphasia 2014. Available at: https://www.rcslt.org/members/docs/aphasia_resource_updatedfeb2014 (accessed February 2018)

[4] United States National Institute of Health (NIH) Health information. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Voice, speech and language: aphasia. Available at: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/aphasia (accessed February 2018)

[5] National Institute on Deafness and Other Communicable Disorders (NIDCD) FactSheet. Voice, speech and language – Aphasia. Available at: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/health/voice/Aphasia6-1-16.pdf (accessed February 2018)

[6] Wallace G, Purdy M & Hasselkus A. Communication after stroke: understanding how stroke affects language & speech. Available at: http://www.strokeassociation.org/idc/groups/stroke-public/@private/@wcm/@hcm/@mag/documents/downloadable/ucm_444442.pdf (accessed February 2018)

[7] Specialist Pharmacy Service. Consultations about oral anticoagulants for patients with aphasia. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/warfarin-consultation-for-patients-with-aphasia/ (accessed February 2018)

[8] Barnett N & Kaher S. The ‘Patient Prompter’. How useful is it to patients? Presented at Health Service Research and Pharmacy Practice conference 3–4 April 2014. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.19019.90403