Shutterstock.com

Polypharmacy means “many medicines” and is often defined as the use of five or more medicines[1]

. However, the number of medicines prescribed is less important than assessing their appropriateness[2],[3],[4],[5]

. Patients can benefit from taking multiple medicines, but pharmacists should determine whether each patient is taking too many medicines individually[2],[3],[4],[5]

.

Further distinctions using the terms ‘appropriate’ or ‘problematic’ can be helpful[2],[3],[4],[5]

:

- Appropriate polypharmacy occurs when practitioners combine best available evidence and clinical judgement with the patient’s values and preferences, along with an assessment of what is realistic for that individual;

- Problematic polypharmacy occurs when multiple medicines are prescribed without considering patients’ wishes or ability to take the medicine, where intended benefits are not realised, and where risks of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and negative outcomes are high.

Incidence of polypharmacy is increasing, both in the UK and worldwide, meaning more people are taking more medicines than ever, with this trend likely to continue[5],[6]

. The number of patients receiving more than five regular medicines has increased three to four fold in the past decade, with one English study quoting an increase from 12% to 49% of the older population[7],[8],[9]

. In Scotland, data from NHS Fife show that, in 2016, 3.5% of the Fife population (n=370,000) was prescribed ten or more medicines daily, equating to around 1 in 30 patients per GP practice, up from 3.2% in 2012.

It is easy to understand how polypharmacy arises, with prescribing being the most common healthcare intervention[6]

. Another contributing factor is that advice is plentiful around initiating medicines, but information on stopping therapy is limited[4]

. Guidelines focus almost exclusively on individual diseases, with frail, older or multimorbid patients largely excluded from trials[10],[11]

.

Patients with multimorbidity often attend several disease-specific clinics and encounter many different specialist prescribers. Multiple prescriber involvement increases the prevalence of problematic polypharmacy; therefore, effective teamwork and holistic prescribing approaches are essential for high-quality care[12],[13],[14]

. Patient involvement in making decisions about their medicines is increasingly being advocated[2]

. However, evidence suggests patient preference does not always influence prescribing decisions[15]

. Many patients feel they have little control over their medicines and are passive recipients of care[4],[5]

.

Why polypharmacy is important

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) has described polypharmacy as a “serious and significant public health challenge”[5]

. The more medicines patients take, the greater the risk of ADRs and hospitalisation, leading to patients becoming less likely to take their medicines as prescribed. Therefore, therapy must be tailored to individuals.

Non-adherence with prescribed medicine is, to varying degrees, common and is frequently not visible to healthcare professionals[5],[7]

. The underuse or erratic use of medicines compromises patient outcomes and must be addressed. Multiple studies have identified a link between the complexity of a medication regimen and non-adherence[16]

. A higher number of medicines and complicated schedules or special instructions (e.g. time of day or food interactions) can all contribute to greater patient difficulty or lack of interest in following treatment recommendations[16]

.

ADRs account for 6.5% of UK hospital admissions (based on adult admissions and a median age of 76 years) and more than 70% of these are deemed avoidable[17]

. A person taking ten or more medicines is estimated to be 300% more likely to be admitted to hospital, although it is difficult to disentangle the effect of polypharmacy from the effect of the underlying conditions[18]

.

Older, frailer patients are particularly vulnerable to ADRs owing to:

- Age-related changes and pathologies (e.g. changes in cognitive function);

- Comorbidity of chronic conditions;

- Changes in pharmacokinetics (e.g. renal elimination of medicine reduced) and pharmacodynamics (e.g. increased sensitivity to certain medicines, such as benzodiazepines and opioids)[19]

.

Rigid adherence to guidelines puts patients at risk. For example, the blanket implementation of all prescribing recommendations within national clinical guidelines for diabetes, depression and heart failure in a comorbid patient potentially generates 49 serious drug–disease interactions (such as metformin in heart failure) and 333 drug–drug interactions (such as hyperkalaemia from concomitant use of angiotensin-converting-enzyme [ACE] inhibitors and spironolactone)[20]

.

Role of the pharmacist in tackling polypharmacy

Pharmacists must become more skilled in interpreting the relevance of available evidence to individual patients. Notably, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) says recommendations:

- Are not mandatory;

- Are ‘guidelines, not tramlines’;

- Do not override professional responsibility to make decisions appropriate to patient circumstances[2]

.

Pharmacists should ensure shared-decision making takes place in all medicine-related conversations; therefore, increasing patient engagement in prescribing decisions is essential[5],[21]

. Complex prescribing regimens place significant demands on patients and are futile if not taken as the prescriber intends.

Pill or treatment burden is increasingly recognised and quantified[5],[22]

. Full adherence to disease-specific guidelines for patients with 6 chronic conditions equates to 18 medicines per day, 7 healthcare visits per month and approximately 81 hours per month of health-related activities[22]

. The Photoguide provides visual examples from the authors’ own practice of treatment burden, and overt and hidden non-adherence.

Photoguide: treatment burden and adherence

Source: Courtesy of Fiona Allan

Increasing patient engagement

Research suggests patients are willing to engage in discussions around medicines[21]

. A recent American survey of 2,121 older adults showed that 92% of older adults were willing to stop one or more medicines if their physician said it was possible; 67% wanted to reduce the overall number of medicines they take[23]

.

Information and choice around medicine positively influences change. Results from the EMPOWER trial show that targeted patient information increased benzodiazepine discontinuation rates at six months (27% of intervention patients vs. 5% of controls)[24]

. Haddad et al. showed less than one third of older adults were aware of potential falls-related side effects of their medicine[25]

. However, most expressed willingness to change these medicines if advised by healthcare professionals.

A recent Canadian pharmacist-led study, the D-PRESCRIBE trial, tested the effect of pharmacists working with both patients and prescribers to reduce inappropriate prescriptions[26]

. Pharmacists targeted patients with educational deprescribing brochures and used evidence-based pharmaceutical opinions to communicate with prescribers. At six months, 43% of the intervention group no longer filled prescriptions for inappropriate medicine compared with 12% of the control group.

Guidance and resources

In the UK and internationally, several guidelines on polypharmacy medicine review exist to support good clinical practice (see Additional resources) and they all endorse a structured, step-wise approach to developing individualised, patient-centred management plans. The guidelines encourage practitioners to undertake reviews that:

- Improve quality of life by reducing treatment burden, adverse events, and unplanned or uncoordinated care;

- Are not single interventions, but part of an ongoing process of reviewing and revisiting treatment decisions;

- Do not have medicines discontinuation as their primary focus.

Existing guidelines vary in the number of steps they identify as essential to undertaking polypharmacy reviews, and the language they use to describe them. Nonetheless, their similarities are greater than their differences. Healthcare professionals should feel empowered to select the guideline, or parts of different guidelines, that work best in their clinical practice. Getting started is essential.

The following sections describe a suggested framework for holistic polypharmacy reviews drawn from these guidelines. Each section aims to capture the main points from within these publications. The framework should be used as a supportive tool and not as a rigid set of instructions to be adhered to. Healthcare professionals may choose to focus on sections they feel are not already adequately incorporated within their own practice.

Aims

Clarify what the patient is taking and if they can manage

The King’s Fund, the Specialist Pharmacist Service and the RPS all identify medicines reconciliation and an assessment of medicines adherence as the starting point of a review[4],[5],[27]

. Do not assume patients are taking, or can take, their medicines as prescribed. It is also advised that patients should bring all medicines, including over-the-counter products, medical devices (such as inhalers and sprays) and supplements to a review to aid this assessment. There is a need to effectively communicate with patients to find out more about the medicine they take (see Box 1)[3],[28]

.

Box 1: communicating with patients about their medicine intake

Ensure that any discussion about ‘medicine’ is all-encompassing and includes not only oral prescribed medicines, but also over-the-counter medicines and supplements, inhalers and topical preparations, such as creams, eye drops or nasal sprays. Patient leaflets can be used to encourage this.

The ‘NO TEARS medication review tool’ provides good examples of questions to encourage honest dialogue about adherence, such as:

- “I realise lots of people do not take all their tablets. Do you have any problems?”;

- “It must be tricky taking so many medicines regularly – are there any you miss out or forget to take?”

Pharmacists should look for potential problems and ask their nurse or GP about them specifically. Examples include:

- Can your patient with dementia realistically adhere to complex administration requirements (e.g. for bisphosphonates)?;

- Can your frail older patient with diabetes realistically apply capsaicin cream four times daily to their feet?;

- Can your patient who needs soluble paracetamol swallow their large calcium and vitamin D caplets?

Be the patient’s advocate with respect to setting appropriate medicine goals and consider asking how many medicines the patient is willing to take.

Explore any systems or prompts that patients use at home to support them in managing their medicines. Establish who (if anyone) provides support to help them take their medicines and consider involving these individuals (with patient consent) early in the development of an appropriate care plan.

Establishing patient priorities

The resource, ‘A Patient Centred Approach to Polypharmacy’, developed by the Specialist Pharmacy Service, reminds healthcare professionals to ask patients what medicines are important to them and what they would like to achieve from their medicines review[27]

. Open questions could include:

- “What do you consider to be your most helpful/least helpful medicine?”;

- “What would you like to discuss or change?”

The ‘What Matters to You?’ campaign encourages more meaningful conversations with patients by[29]

:

- Asking what matters;

- Listening to what matters;

- Doing what matters.

The ‘Me and My Medicines’ campaign is another useful tool to support patients and professionals in having better conversations around medicines[30]

. Pharmacists should enquire initially about their patients’ general health and, more specifically, what they would like to do that their medicines currently do not allow them to do (e.g. walk further or sleep better).

Needs

Check for ongoing valid indications

It is essential to check for an ongoing valid indication for each prescribed item. Medicines may have been initiated appropriately, but may no longer be indicated owing to change in evidence or clinical status. Reviewing evidence from local and national guidelines, and its applicability to the patient, can inform deprescribing decisions.

Also consider:

- Duration — was long-term treatment intended?

- Duplication — are there multiple drugs for the same indication?

- Undertreatment — are there clinical indications that aren’t being addressed?

Consider essential and non-essential items

When making deprescribing decisions, it is important to assess whether medicines are essential because they are fulfilling replacement functions (e.g. levothyroxine), or preventing rapid symptomatic decline (e.g. treatment for Parkinson’s disease or heart failure medicines)[3]

.

Consider how to deprescribe

If a medicine is deemed non essential and suitable for discontinuation, deciding how to stop it (either abruptly or gradually) is crucial to avoiding discontinuation effects[31]

.

Effectiveness

How to assess effectiveness

Pharmacists should consider whether all medicines currently prescribed are achieving beneficial outcomes for their patients and, if not, the reason why and whether the prescription should continue.

Effectiveness can be assessed in different ways, including the monitoring of:

- Clinical signs and symptoms — many of which can be quantitatively measured through the use of validated scoring tools (e.g. pain, breathlessness or urinary frequency);

- Clinical parameters — for example, blood pressure (BP) reduction, cholesterol reduction, patterns of drug consumption (such as a reduction in the use of glyceryl trinitrate [GTN] spray, or ‘as required’ short-acting bronchodilators, or breakthrough analgesia).

Patients may appear to have a valid ongoing clinical indication for a medicine, for example, history of urinary frequency in a patient receiving a bladder antimuscarinic medicine. However, accurately assessing the effectiveness of ongoing medicine can be challenging in long-established therapy, as the opportunity to undertake them before and after measurements following initiation has gone. For established symptomatic treatments, a trial withdrawal is often the most appropriate way to assess ongoing effectiveness with planned monitoring to capture any change in symptoms on discontinuation.

Drug efficacy targets around essential clinical parameters, such as BP, glycaemic control and cholesterol, exist within national clinical guidelines, but must be considered in the context of what is realistic for the individual (based on frailty and life expectancy) and considering the patient’s wishes.

It is important to recognise that treatment goals/targets change as people age, become frailer and their personal priorities alter. As age and medicine burden increases, patients may favour medicines offering symptomatic benefit and improved quality of life, rather than preventative medicines taken to reduce risks of future events.

Determining frailty

Frailty is an important concept for pharmacists to be aware of as it is a stronger predictor of medicine-related harm than age alone[32]

. NICE multimorbidity guidance suggests that walking speed is a simple way of screening for frailty[2]

. This can be done informally (e.g. time taken to walk from the waiting room) or formally (e.g. taking more than five seconds to walk four metres, which indicates frailty).

Several validated assessment tools exist to classify severity of frailty[2]

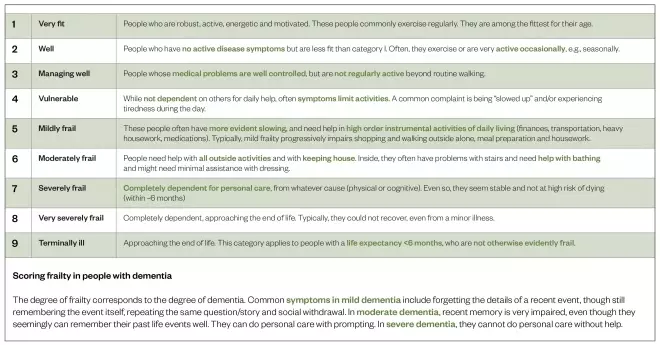

. The Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale (see Figure) is commonly used in clinical practice[33]

. Another tool used by GP practices to identify and target patients identified as being potentially frail is the electronic frailty index (EFI)[34]

.

Figure: Clinical frailty scale

Source: Reproduced with permission from Kenneth Rockwood

[73]

This scale is used to classify frailty severity in clinical practice

Setting realistic targets

Knowledge of frailty is essential in devising individualised treatment targets.

If BP is considered as an example, NICE hypertension guidelines set a BP target of <140/90mmHg for people aged under 80 years without comorbidities[32]

. However, in frail, multi-morbid, older patients, there is increasing evidence that tight BP control may be harmful.

Canadian consensus BP guidelines for frail, older adults advocate reducing antihypertensives if systolic BP is <140mmHg[33]

. The PARTAGE study shows that frail institutionalised patients with a systolic BP of <130mmHg on two or more antihypertensive drugs are at increased risk of death[34]

. The Leiden 85-plus study further links lower BP with higher all-cause mortality and cognitive decline in the oldest patients[35]

.

With respect to diabetic control, a recent primary care study in the Netherlands found 20% of older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were overtreated with probable harmful consequences[36]

. A consensus statement on T2DM management in older people proposes HbA1c targets based on frailty: <58mmol/L (7.5%) in fit older adults; <64mmol/L (8%) in moderate-severely frail patients; and <70mmol/L (8.6%) in severely frail patients[37]

.

Defining achievable outcomes

It is important to acknowledge limitations of medicine and set realistic expectations and measurable treatment goals.

Considering chronic pain, a 30–50% reduction in pain intensity at four to six weeks, or specific improvements in function or sleep, would be acknowledged as a realistic goal. Numerous assessment tools exist to support assessment of analgesic efficacy[38]

.

In this case, setting expectations that medicine is unlikely to eradicate pain is important. This is specifically true for opioids in chronic pain where research suggests that nine out of ten patients do not derive meaningful benefit, but remain exposed to significant risk[39]

. Goals should focus on reducing pain to tolerable and manageable levels to support active self-management.

Presenting evidence for effectiveness

When evaluating ongoing efficacy of medicine, numbers needed to treat (NNT) data can be helpful. Various NNT websites exist and the NHS Scotland polypharmacy guideline has a dedicated section on NNTs for common therapeutic interventions[3],[40],[41]

.

Safety

Review current and future risk

Medication risk is defined in different ways. Many tools exist to support healthcare professionals in identifying and prioritising high-risk drugs during polypharmacy reviews. There is evidence that pharmacists can reduce iatrogenic disease (i.e. illness caused by treatment or examination) by targeting combinations of high-risk medicines and high-risk prescribing scenarios[42],[43]

.

Another essential component of the pharmacist’s role with respect to medicines safety is to be alert to the presence of the prescribing cascade where patients have been prescribed medicines to treat the side effects of other medicines, rather than stopping the offending medicine[31]

.

Potentially inappropriate prescriptions

The validated tools STOPP/START, STOPPFrail and Beers Criteria identify potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) in older patients and subdivide these by therapeutic category for ease of reference[44],[45],[46]

.

This is mirrored in national guidelines, such as:

- All Wales Strategy Group — Supplementary Guidance. BNF Sections to Target[7]

; - Scottish polypharmacy guidance — Table 2b. An overview of therapeutic groups under each step[3]

.

Hospital admission and falls

Data also exist on medicines strongly correlated with risk of hospital admission and falls[17],[47],[48],[49],[50],[51]

.

Four groups of medicines account for more than 50% of preventable drug-related hospital admissions[47]

:

- Antiplatelets;

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs);

- Diuretics;

- Anticoagulants.

Medication-related falls most commonly occur owing to medication-induced:

- Sedation (e.g. benzodiazepines);

- Hypotension (e.g. ACE inhibitors);

- Bradycardia (e.g. donepezil);

- Syncope (temporary loss of consciousness, e.g. GTN)[49]

.

High-risk drug combinations

Pharmacists should consider medication risk not just individually, but cumulatively. It can be helpful to think about risk in terms of clinical systems (e.g. gastrointestinal [GI] or renal risk) or specific clinical problems (e.g. poor cognition, delirium and falls).

The NHS Scotland polypharmacy guidance includes a table and the ‘Cumulative toxicity tool’, which highlights where an ADR may occur owing to a cumulative effect of multiple medicines[3]

. For example:

- GI bleeding is more likely in the context of combinations of NSAIDs, corticosteroid, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)/serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressants, antiplatelets and/or anticoagulant prescriptions;

- Renal injury is increased as a result of co-prescribing diuretics, ACE inhibitor/angiotensin-II-receptor antagonists and NSAIDs)[51],[52]

.

In the context of cognition, delirium and falls, tools such as the drug burden index (DBI) and anticholinergic cognitive burden (ACB) scale are invaluable[53],[54]

. The DBI is an evidence-based tool that measures patient exposure to medicines with sedative and anticholinergic properties associated with impairment in cognitive and physical function. The ACB scale provides a way of quantifying a medicine’s anticholinergic affinity.

Many anticholinergic drugs are included in the STOPP and Beers Criteria tools as PIPs. However, as combining anticholinergic drugs increases the risk of ADRs (including confusion, falls and death), it is important for healthcare professionals interacting with older or frail patients to become familiar with ACB scores of commonly prescribed medicines. Scores of three or more for individual drugs or medicine combinations is considered significant.

Drug–disease interactions

Risks can also be amplified in the context of a patient’s comorbidities. For example, the stroke risk of antipsychotics is magnified in patients with dementia, so the DBI and ACB scale are invaluable[55],[56]

.

Risk identification and minimisation

Effective clinical questioning is crucial in identifying the presence of side effects in individuals (see Box 2). Patients may not link certain symptoms to their medicines and ADRs can go undiagnosed unless healthcare professionals specifically ask about them[57]

. It can be difficult for both patients and healthcare professionals to distinguish between symptoms of the condition and side effects of particular drugs, especially as many side effects (e.g. nausea, dizziness, fatigue and headache) are common symptoms of frequently occurring conditions[58]

. No algorithm for identifying ADRs has been shown to be faultless and research indicates that using different questioning methods yields differing results[57],[59],[60]

.

Box 2: consultation skills: risk assessment of medicines

In general, open questions can be useful to start with, for example: “Tell me whether any of your medicines cause side effects or problems.” Specific, closed questions focusing on the most common adverse drug reactionss associated with the medicine being discussed, can follow. For example:

- “Do you think [name of medicine] causes any side effects or makes you feel anything out of the ordinary?”

- “Specifically, are you bothered with dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, poor balance or problems with your memory?”

A mixture of open, closed and checklist questions within a consultation may give the most comprehensive results.

The absence of symptoms does not mean absence of future risk. For example:

- Patients on agents that increase risk of GI events should be told that dyspeptic symptoms are a poor predictor of risk, with less than half of ulcer complications (GI bleeds) presenting with any warning signs[61]

; - Patients on agents with a high ACB score should be aware that increases in this score are associated with reductions in cognition and memory over time (as measured by the ‘mini mental state examination’)[54]

; - Postural hypotension is a risk factor for falls irrespective of whether it is asymptomatic or symptomatic. One study identified the prevalence of postural hypotension as 18% in community dwelling patients aged over 65 years, but only 2% of these patients displayed postural hypotension symptoms[62],[63],[64]

.

Therefore, proactive provision of patient information around risk, active interventions to stop or reduce the dose of high-risk medicines and the implementation of active monitoring, remains the responsibility of pharmacists undertaking polypharmacy reviews.

Efficiency

Consider cost-efficiency and simplicity

Financial pressures on the NHS are severe and show no sign of easing, meaning that healthcare professionals have a duty to consider the cost-effectiveness of the treatments they are providing[65]

. The primary focus of polypharmacy reviews is improved clinical outcomes and quality of life for patients. However, there is also potential to save money by:

- Identifying and addressing non-adherence;

- Discontinuing or reducing PIPs;

- Preventing costs associated with avoidable ADRs (e.g. costly hospital admissions)[3],[66],[67],[68]

.

Considering cost-effective formulations and formulary options provide other opportunities for savings.

Cost benefits must be offset against the resource cost of carrying out a review. The Scottish polypharmacy guidance includes an appendix (‘Health economics analysis of polypharmacy reviews’) suggesting overall cost benefits, especially when targeted at high risk individuals[3]

.

Pharmacists can also use their knowledge of drug dosing and formulations to simplify drug regimens for patients, for example:

- Selecting drugs within the same class with simpler dosage schedules (e.g. bisoprolol once daily vs. atenolol twice daily);

- Changing medicine timing to support adherence (e.g. atorvastatin in the morning vs. simvastatin at night);

- Reducing medicine frequency to support adherence (e.g. pregabalin 75mg twice daily vs. pregabalin 50mg three times daily).

Acceptability

Agreeing an acceptable plan for change

Polypharmacy reviews should involve the patient to encompass shared-decision making. The ‘Choosing Wisely UK’ campaign summarises four questions that should be considered before initiating or changing a patient’s medicines[69]

:

- What are the benefits?

- What are the risks?

- What are the alternatives?

- What if I do nothing?

For example, if the patient is stepping down their diabetic medicine, you may wish to discuss the four questions as follows:

- The benefits could include fewer medicines for the patient to take and a lower risk of hypoglycaemic events;

- The risks could involve the chance that diabetic symptoms may return in the short to medium term (e.g. thirst, polyuria or increased risk of infection) and that diabetic complications might happen in the long term;

- The alternatives may be to stop one medicine completely (e.g. gliclazide 80mg twice daily, or alternatively reduce to the dose to 40mg twice daily and recheck diabetic control);

- If nothing is done, there may be an increased risk of a hypoglycaemic episode and an increased requirement for blood sugar monitoring to mitigate risk.

It is unlikely that it will be appropriate to make all of the possible changes to a patient’s medicine in one consultation. Agreeing the number of appropriate changes at each stage is something that must be done in collaboration with patients. For frail patients, those living alone or with cognitive impairment, more cautious plans for change may be required and the involvement of carers or family members should also be considered.

Document

Ensure the plan is clearly documented and shared with others involved in the patient’s care. Using a defined and agree template within the clinical record may help standardise entries. In NHS Fife, a computerised template with the GP practice clinical system (i.e. EMIS) is used across the primary care pharmacy team, which supports consistent documentation and the extraction of data around review outcomes. For example, polypharmacy reviews undertaken in Scotland are coded with the nationally agreed read code ‘8B31B’.

It may be appropriate to share the plan (with the patient’s permission) with others involved in their care (e.g. family members/care givers) their community pharmacy or any hospital specialists who see the patient regularly. In some cases, discussing the plan with others prior to implementation may be the best step. ‘My medication passport’ (a written record of a patient’s medicines) is a useful resource for improving communication across the interface[70]

.

Monitor

Polypharmacy reviews cannot be viewed as one-off events and pharmacists must explicitly state when they plan to follow up with a patient and what they intend to monitor to ensure changes are both safe and effective.

Medicine changes must be viewed as trials and patients should be provided with realistic timescales in which to expect effects to be seen. For example, it may be appropriate to tell patients that effects could be found four to six weeks after changing their BP medication, or three months after changing their diabetic medication. Reassuring patients that they have the opportunity to revert, if changes are unsuccessful is important to help ensure they feel in control of their own care.

Monitoring for safety and efficacy can be achieved through a combination of:

- Biochemical and clinical assessment (e.g. urea and electrolytes or BP);

- Clinical questioning on:

- Changes in patterns of drug use (e.g. reduction or increase in salbutamol use, increase in glyceryl trinitrate spray use, reduction in as required laxatives) can also be useful elements of monitoring.

Safety-netting around changes is essential, with patients told clearly what symptom changes to look out for and to report any worsening or worrying changes to the pharmacist or broader healthcare team in an appropriate timescale. For example, in a patient in whom a diuretic dose has been reduced, it would be important to advise the patient that if shortness of breath or ankle swelling worsens, they should contact their healthcare team as a matter of urgency to re-instate their previous dose with immediate effect.

Additional resources

- Multimorbidity and polypharmacy. NICE key therapeutic topic (KTT18). 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt18

- Polypharmacy guidance: realistic prescribing. 3rd Edn. 2018. Scottish government. Available at: https://www.therapeutics.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Polypharmacy-Guidance-2018.pdf

- Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation: Making it safe and sound. The King’s Fund. 2013. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf

- Polypharmacy: guidance for prescribing. All Wales Medicines Strategy Group (AWSG) 2014. Available at: http://awmsg.org/docs/awmsg/medman/Polypharmacy%20-%20Guidance%20for%20Prescribing.pdf

- A patient-centred approach to polypharmacy. NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service 2017. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/polypharmacy-oligopharmacy-deprescribing-resources-to-support-local-delivery/

- Guiding Principles for the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity: An Approach for Clinicians. American Geriatrics Society. 2012. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4450364/

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

References

[1] Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017;17(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy. Key therapeutic topic [KTT18]. 2019. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt18 (accessed November 2019)

[3] Scottish Government Polypharmacy Model of Care Group. Polypharmacy Guidance: Realistic Prescribing. 2018. Available at: https://www.therapeutics.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Polypharmacy-Guidance-2018.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[4] Duerden M, Avery T & Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation. Making it safe and sound. The King’s Fund. 2013. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[5] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Polypharmacy: Getting our medicines right. 2019. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/setting-professional-standards/polypharmacy-getting-our-medicines-right (accessed November 2019)

[6] Mair A, Fernandez-Llimos F, Alonso A et al. Polypharmacy Management by 2030: A patient safety challenge. 2017. Available at: http://www.simpathy.eu/sites/default/files/Managing_polypharmacy2030-web.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[7] All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. Polypharmacy: Guidance for Prescribing. 2014. Available at: http://awmsg.org/docs/awmsg/medman/Polypharmacy%20-%20Guidance%20for%20Prescribing.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[8] Moriarty F, Hardy C, Bennett K et al. Trends and interaction of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in primary care over 15 years in Ireland: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008656. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008656

[9] Pike H. Deprescribing: the fightback against polypharmacy has begun. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2018;301(7919). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2018.20205686

[10] NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. NHSGGC Mindful Prescribing Strategy – Polypharmacy. 2012. Available at: http://www.ggcprescribing.org.uk/media/uploads/prescribing_resources/mindful_prescribing_strategy_-_1212.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[11] Guthrie B. Optimising prescribing in primary care in the face of multimorbidity and polypharmacy. 2018. Available at: http://www3.ha.org.hk/haconvention/hac2018/proceedings/downloads/PS7.1.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[12] Hilmer SN. The dilemma of polypharmacy. Aust Prescr 2008;31:2–3. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2008.001

[13] Tamblyn R, McLeod P, Abrahamowicz M et al. Do too many cooks spoil the broth? Multiple physician involvement in medical management of elderly patients and potentially inappropriate drug combinations. CMAJ 1996;154(8):1177–1184. PMID: 8612253

[14] Barber ND, Alldred DP, Raynor DK et al. Care homes’ use of medicines study: prevalence, causes and potential harm of medication errors in care homes for older people. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:341–346. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.034231

[15] Dooley J, Bass N, Livingston G & McCabe R. Involving patients with dementia in decisions to initiate treatment: effect on patient acceptance, satisfaction and medication prescription. Br J Psychiatry 2019;214(4):213–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.201

[16] McDonald MV, Peng TR, Sridharan S et al. Automating the medication regimen complexity index. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20(3):499–505. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001272

[17] Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15

[18] Payne RA, Abel GA, Avery AJ et al. Is polypharmacy always hazardous? A retrospective cohort analysis linked to electronic health records from primary and secondary care. BJ Clin Pharmacology 2014; 77(6):1073–1082. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12292

[19] Mortazavi SS, Shati M, Keshtkar A et al. Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010989. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010989

[20] Dumbreck S, Flynn A, Nairn M et al. Drug-disease and drug-drug interactions: systematic examination of recommendations in 12 UK national clinical guidelines. BMJ 2015;350: h949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h949

[21] King E, Taylor J, Williams R et al. The MAGIC programme: evaluation. 2013. Available at https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/TheMagicProgrammeEvaluation.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[22] Buffel du Vaure C, Ravaud P, Baron G et al. Potential workload in applying clinical practice guidelines for patients with chronic conditions and multimorbidity: a systematic analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6(3):e010119. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010119

[23] Reeve E, Wolff JL, Shekan M et al. Assessment of Attitudes Toward Deprescribing in Older Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(12):1673–1680. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4720

[24] Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R et al. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(6):890–898. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949

[25] Haddad YK, Karani MV, Bergen G & Marcum ZA. Willingness to Change Medications Linked to Increased Fall Risk: A Comparison between Age Groups. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;67(3):527–533. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15696

[26] Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A et al. Effect of a Pharmacist-Led Educational Intervention on Inappropriate Medication Prescriptions in Older Adults. The D-PRESCRIBE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018;320(18):1889–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16131

[27] NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service. A patient centred approach to polypharmacy. Polypharmacy Resource 2 July 2015 V10 (NB) (LO) (KS). Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/polypharmacy-oligopharmacy-deprescribing-resources-to-support-local-delivery (accessed November 2019)

[28] Lewis T. Using the NO TEARS tool for medication review. BMJ 2004;329:434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7463.434

[29] Healthcare Improvement Scotland. What Matters to You? Campaign. 2019. Available at: https://www.whatmatterstoyou.scot (accessed November 2019)

[30] Me and My Medicines. The Medicines Communication Charter. Available at: https://meandmymedicines.org.uk/the-charter (accessed November 2019)

[31] Frailty, polypharmacy and deprescribing. Drug Ther Bull 2016:54(6):69–72. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2016.6.0408

[32] Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S et al. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

[33] Rajkumar C, Ali K & Parekh N. Frailty predicts medication-related harm requiring healthcare: a UK multicentre prospective cohort study. 2018. Available at: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/77388 (accessed November 2019)

[34] NHS England. Electronic Frailty Index. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/older-people/frailty/efi (accessed November 2019)

[35] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults. Quality Standard [QS28]. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs28 (accessed November 2019)

[36] Hart HE, Rutten GE, Bontje KN & Vos RC. Overtreatment of older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20(4):1066–1069. doi: 10.1111/dom.13174

[37] Strain WD, Hope SV, Green A et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older people: a brief statement of key principles of modern day management including the assessment of frailty. A national collaborative stakeholder initiative. Diabet Med 2018;35(7):838–845. doi: 10.1111/dme.13644

[38] NHSGGC Library Network. Diagnostic tools and outcome measures specific to pain. Available at: https://www.quest.scot.nhs.uk/hc/en-gb/sections/115000816529-Pain (accessed November 2019)

[39] Stewart C. Where now for opioids in chronic pain? Drug Ther Bull 2018;56:118–122. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2018.10.000007

[40] Dr Chris Cates’ EBM website. Available at: http://www.nntonline.net (accessed November 2019)

[41] The NNT. Quick summaries of evidence-based medicine. Available at: http://www.thennt.com (accessed November 2019)

[42] Morrison C & MacRae Y. Promoting Safer Use of High-Risk Pharmacotherapy: Impact of Pharmacist-Led Targeted Medication Reviews. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 2015;2:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s40801-015-0031-8

[43] Avery AJ, Rodgers S, Cantrill JA et al. A pharmacist-led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicentre, cluster randomised, controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. The Lancet 2012;9823:1310–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61817-5

[44] O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015;44(2):213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145

[45] Lavan AH, Gallagher P, Parsons C & O’Mahony D. STOPPFrail (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy): consensus validation. Age Ageing 2017;46(4):600–607. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx005

[46] American geriatrics Society Beers criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(4):674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767

[47] Howard RL, Avery AJ, Slavenburg S et al. Which drugs cause preventable admissions to hospital? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63(2):136–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02698.x

[48] Dreischulte T & Guthrie B. High-risk prescribing and monitoring in primary care: how common is it, and how can it be improved? Ther Adv Drug Saf 2012;3(4):175–184. doi: 10.1177/2042098612444867

[49] Darowski A, Dwight J & Reynolds J. Medicine and Falls in Hospital: Guidance sheet. 2011. Available at: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/933 (accessed November 2019)

[50] de Jong MR, Van der Elst M & Hartholt KA. Drug-related falls in older patients: implicated drugs, consequences, and possible prevention strategies. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2013;4(4):147–154. doi: 10.1177/2042098613486829

[51] Lapi F, Azoulay L, Yin H et al. Concurrent use of diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: nested case-control study. BMJ 2013;346:e8525. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8525

[52] Waitemata District Health Board. The Triple Whammy - Safe Prescribing - A Dangerous Trio. 2014. Available at: http://www.saferx.co.nz/assets/Documents/full/66598cdaca/triplewhammy.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[53] Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM et al. Drug burden index score and functional decline in older people. Am J Med 2009;122(12):1142–1149.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.02.021

[54] Aging Brain Program of the Indiana University Center for Aging Research. Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale. 2012. Available at: http://www.miltonkeynesccg.nhs.uk/resources/uploads/ACB_scale_-_legal_size.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[55] Douglas IJ & Smeeth L. Exposure to antipsychotics and risk of stroke: self controlled case series study. BMJ 2008;337:a1227. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1227

[56] Valkhoff VE, Sturkenboom MC & Kuipers EJ. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding associated with low-dose aspirin. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2012;26(2):125–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.01.011

[57] Ferner RE & McGettigan P. Adverse drug reactions. BMJ 2018;363:k4051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4051

[58] Gavin F. Helping patients understand adverse drug reactions. BMJ Opinion. 2018. Available at: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/11/06/frank-gavin-helping-patients-understand-adverse-drug-reactions (accessed November 2019)

[59] Bent S, Padula A & Avins AL. Brief Communication: Better Ways To Question Patients about Adverse Medical Events A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(4):257–261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-4-200602210-00007

[60] Allen EN, Chandler CI, Mandimika N et al. Eliciting adverse effects data from participants in clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;1:MR000039. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000039.pub2

[61] MacRae F, MacKenzie L, McColl K & Williams D. Strategies against NSAID-induced gastrointestinal side effects: part 1. Pharm J 2010;(272):187–189. URI: 10996993

[62] McDonagh ST, Mejzner N & Clark CE. Prevalence of postural hypotension in primary care, community and institutional care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Society for Academic Primary Care. ASM 2018 - London. Available at: https://sapc.ac.uk/conference/2018/abstract/prevalence-of-postural-hypotension-primary-care-community-and-institutional (accessed November 2019)

[63] Lanier JB, Mote MB & Clay E. Evaluation and management of orthostatic hypotension. Am Fam Physician 2011;84(5):527–536. PMID: 21888303

[64] Gupta V & Lipsitz LA. Orthostatic hypotension in the elderly: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med 2007;120(10):841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.023

[65] Robertson R, Wenzel L, Thompson J et al. Understanding NHS financial pressures: how are they affecting patient care? Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/understanding-nhs-financial-pressures (accessed November 2019)

[66] Mirk A, Echt KV, Vandenberg AE et al. Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders: Can We IMPROVE Outcomes? Fed Pract 2016;33(3):39–41. PMID: 27536053

[67] Kojima G, Bell C, Tamura Bet al. Reducing cost by reducing polypharmacy: the polypharmacy outcomes project. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13(9):818.e11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.019

[68] Rollason V & Vogt N. Reduction of polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review of the role of the pharmacist. Drugs Aging 2003;20(11):817–832. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320110-00003

[69] Academy of Royal Colleges. UK Choosing Wisely campaign. 2019. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.co.uk (accessed November 2019)

[70] National Institute for Health Research. My Medication Passport. 2018. Available at: http://clahrc-northwestlondon.nihr.ac.uk/resources/mmp (accessed November 2019)

[71] Kroenke K, Spitzer RL & Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

[72] Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

[73] Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005 30;173(5):489–495. Available at: https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/clinical-frailty-scale.html