Sergio Azenha / Alamy Stock Photo

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurological disorder in which there is progressive death of dopaminergic neurones in the substantia nigra — the part of the mid-brain responsible for managing movement and the dopaminergic system — with more than 50% of cell death occurring before symptom manifestation. The subsequent deficiency of dopamine synthesis, owing to this cell death, leads to the progression of motor symptoms including bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor and postural instability[1],[2]

.

Around 137,000 people in the UK have a PD diagnosis[3]

. The cause of the disease is yet to be discovered, but a combination of environmental and genetic factors are thought to increase its risk. Despite this, there is a lack of robust, large-scale evidence of a definitive link between any specific environmental risk factors[4]

. Around 20% of patients affected by PD have a first-degree relative that is affected by the disease

[1]. Prevalence is higher with increasing age and men appear to be at higher risk of developing the disease than women[1],[3]

. Patients with PD have a reduced life expectancy and studies have suggested up to a five-times higher mortality rate than people in the same age group without PD[5]

.

People with PD are particularly vulnerable and are likely to be admitted to hospital for the treatment of conditions not directly related to the condition[6]

. Results from a cross-sectional study analysis of the English Hospital Episodes Statistics by Low et al. in 2015 showed that there were 324,055 PD admissions for 182,859 patients between 2009 and 2013, including multiple admissions for each patient

[6]. The total cost of admissions for people with PD over four years was more than £900m. The results also showed that 72% of these admissions were emergency admissions and resulted in a cost of £777m for the duration of their inpatient stay. The study also reported that patients with PD were more likely to stay in hospital for longer than three months[6]

.

Symptoms

PD typically presents with a range of symptoms that are grouped as motor and non-motor, but patients may experience both.

Motor:

- Tremor;

- Bradykinesia;

- Dyskinesia

- Rigidity;

- Falls and dizziness;

- Freezing of gait;

- Muscle cramps and dystonia;

- End-of-dose deterioration (i.e. deteriorating effect before the next tablet is due)[1]

.

Non-motor:

- Autonomic — postural hypotension, urinary urgency, erectile dysfunction, sweating;

- Gastrointestinal — nausea, constipation, volvulus (when a loop of intestine twists around itself causing bowel obstruction);

- Speech and swallow — drooling, dysarthrophonia (a voice and speech disorder), impaired swallowing;

- Respiratory — aspiration pneumonia (if the swallow reflex is impaired);

- Neuropsychiatric — mild memory and thinking difficulties, anxiety, dementia, depression, impulse control disorders, hallucinations, and delusions. Patients with PD are susceptible to delirium, which may be secondary to constipation, pain, medication, infection, dehydration or electrolyte disturbances;

- Restless leg syndrome;

- Pain;

- Fatigue[1]

.

Each patient has an individual experience; however, the pattern of progression generally consists of four stages:

- Early — when the patient is first experiencing symptoms and is initially diagnosed;

- Maintenance — when patient is likely to achieve almost complete relief from symptoms with medication;

- Complex or advanced stage — symptoms have more effect on daily quality of life;

- Palliative — non-motor symptoms become the most prominent medical problem and the aim of therapy is to provide relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of the condition[1]

.

Pharmacological treatment must be tailored to meet the needs of each patient. There is currently no treatment that slows the progression of the disease and pharmacological therapies are aimed at the management of symptoms. Initiation or alteration of PD medications must only be implemented on the advice of a PD specialist[1]

.

Pharmacological management

Levodopa, a dopamine precursor, remains the ‘gold standard’ for the treatment of PD where motor symptoms have a significant impact on the patients’ quality of life. It is usually given in combination with an aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor (e.g. benserazide or carbidopa). Treatment with a dopamine precursor aims to achieve normal movement and reduce motor symptoms[1]

.

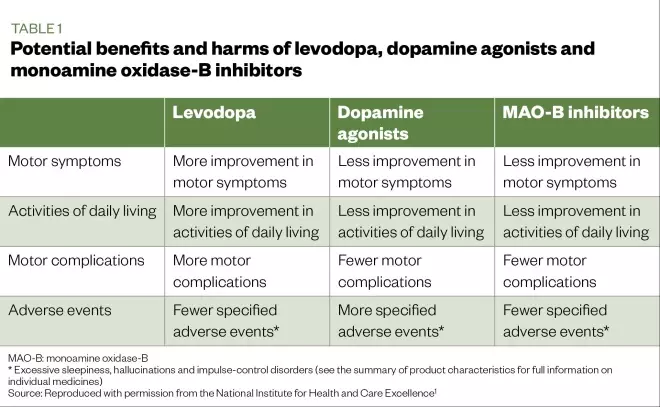

Various other drugs (e.g. monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors, dopamine agonists) may also be used; however, the risk of side effects (e.g. impulse control disorders, hallucinations and daytime sleepiness) is higher than that of the levodopa preparations. The potential benefits and harms of first-line medicines used to manage PD are summarised in Table 1. More detailed information on the management of PD is included in ‘Parkinson’s disease: management and guidance’ (Clinical Pharmacist 2018;10[8]).

Table 1: Potential benefits and harms of levodopa, dopamine agonists and monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors

Patients taking levodopa long term may begin to experience motor fluctuations that result in decreased mobility, dependence and reduced quality of life. Motor fluctuations occur owing to the imbalance of dopamine. Patients may experience end-of-dose deterioration, also known as ‘wearing off’, where the patient’s dopamine levels drop as the time of the next dose approaches, resulting in the progression of motor symptoms. Patients may also experience dyskinesias[1]

,[2]

.

A catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor may be added to levodopa therapy for patients who develop motor fluctuations. Other treatments include oral amantadine, subcutaneous apomorphine and deep-brain stimulation[1]

.

Hospital management

It is acknowledged that the service provided for patients with PD, when they are admitted to hospital, requires improvement. Medicine management is often compromised by a lack of awareness, and a lack of systems and procedures to prevent delayed/missed doses or incorrect prescribing of time-critical PD medicines[7]

.

Patients with PD may be admitted to general medical wards where staff may not recognise the importance of seeking advice from the specialist PD nurse at the earliest opportunity to optimise management of the patient’s PD during their stay. However, ward pharmacists should highlight the urgency of timely PD medication administration, facilitating supply, and ensuring medications are prescribed correctly.

Multiple sources of information should be used to obtain an accurate history, with medicines reconciliation undertaken within the first 24 hours of admission into hospital[8]

. Obtaining an accurate drug history is pivotal to ensure correct prescribing and the timely supply and administration of medicines for PD, this should be sought from a range of sources. For example:

- The summary care record;

- The patient’s own medicines;

- The patient/relative;

- Clinical letters sent to the patient;

- Any previous discharge summaries;

- Any care home records (if possible).

It is important to recognise that an incomplete or inaccurate drug history may lead to delayed or omitted doses. This may be particularly problematic at weekends, when pharmacists may not be present on the wards to conduct medication histories.

As PD medicines are time-critical and delays can lead to deterioration of the patient’s condition it is imperative that:

- PD medicines are ordered from the pharmacy as a matter of priority to prevent omission of doses if the patient’s own supply of medicine is not available;

- Medicines are provided as a matter of urgency. Lack of awareness may highlight the learning needs of the wider team;

- Prescribed medicines are administered at the specific times they normally take them;

- Patients are assessed to determine if they can safely self-administer their PD medicines – this should adhere to local policies[9]

.

Risk of omitting or delaying PD medicines

PD medication should not be stopped abruptly and should always be given on time. Late or missed doses may result in patients’ swallowing, speech and mobility being affected, leading to further difficulties. In addition, delays in the administration of medicines can lead to an increased risk of falls, care needs, pain, and distress, and may lengthen the hospital stay. The following points highlight the seriousness that delaying or omitting a PD medicine may lead to:

- Deterioration of swallowing ability — this leads to a higher than normal risk of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia;

- Exacerbation of PD symptoms — both motor and non-motor symptoms are more likely to present;

- Deterioration in long-term PD control — there is a risk of a permanent reduction in mobility;

- Dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome — a complication PD patients undergo when their dopamine agonist tapers, resulting in physical (e.g. pain or orthostatic hypotension) and psychiatric (e.g. anxiety, panic attacks, depression or psychosis) consequences. This can cause significant distress to patients. The consequences, such as muscle spasms and freezing of gait, resolve on replacement of the dopamine agonist;

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome — this life-threatening reaction occurs in response to neuroleptic or antipsychotic medication. It presents with pyrexia, fever, confusion, raised creatine kinase, muscle rigidity, and altered consciousness. The onset can take up to nine days and can cause significant mortality;

- Death — patients with PD have greater in-hospital mortality. Ensuring patients receive their usual medication and timely specialist review will reduce this risk[7],[9],[10]

.

Management of non-motor symptoms and associated complications

Although the motor symptoms are often what define the condition, the management of non-motor symptoms and PD associated complications is essential in ensuring optimal patient care.

Nausea and vomiting

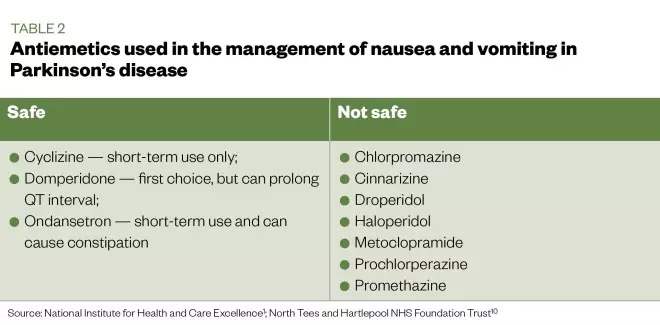

The initiation of PD medicines, and increases or changes of dose, can lead to nausea and vomiting. This may settle over time as the patient develops tolerance, but patients should also be advised to take their medicine with food to reduce nausea. However, if nausea and vomiting persist, pharmacological management may be necessary. Careful consideration of drug interactions and comorbidities should influence the choice of anti-emetic; certain anti-emetics (see Table 2) are not considered to be safe in PD in any situation[1]

.

Table 2: Antiemetics used in the management of nausea and vomiting in patients with Parkinson’s disease

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[1]

; North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust[10]

.

Domperidone is the first-choice anti-emetic for patients with PD; however, this should be used with caution as it can prolong the QT interval — a precursor for further cardiovascular complications. Alternatively, cyclizine and ondansetron may be considered for short-term use, as the use of ondansetron can potentially cause constipation[1]

. Although metoclopramide, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, prochlorperazine, promethazine, and cinnarizine are used for the management of nausea and vomiting, these must be avoided as they are dopamine blockers and can lead to worsening of motor symptoms[10]

.

Vitamin D deficiency

The increased risk of vitamin D deficiency, owing to reduced mobility and therefore a potential reduction in time spent outdoors, is a complication of PD that, in turn, leads to an increased risk of osteoporosis. Pharmacists can recommend the addition of vitamin D supplementation when reviewing PD medicines as an intervention to improve bone health[1]

. Poor mobility can also lead to an increased risk of falls and subsequent fractures; therefore, early intervention from ward physiotherapists should be sought[1]

.

Orthostatic hypotension

This is a fall in blood pressure on standing, also known as postural hypotension. This can precipitate falls and, therefore, requires management. A medication review should be undertaken for patients with orthostatic hypotension to help determine if dose reductions or medicine discontinuations (e.g. antihypertensives or diuretics) are required.

Compression stockings may be considered in order to improve blood circulation and reduce the effects of orthostatic hypotension, provided the patient does not have arterial insufficiency. Midodrine or fludrocortisone, which raise blood pressure, although unlicensed, may be initiated by a specialist for the management of orthostatic hypotension[1],[10]

.

Delirium

Patients with PD are susceptible to developing delirium. This may be caused by infection, dehydration, constipation, electrolyte disturbances or PD medicines. In all cases, the underlying cause should be identified and treated.

PD specialists recommend the use of lorazepam (or clonazepam) as a first-line treatment in the acute phase of delirium or confusion. If longer-term treatment is indicated, atypical antipsychotics (e.g. quetiapine, which has the lowest risk of side effects in PD patients) may also be considered. It should be noted these treatments may only be initiated on the advice of a PD specialist[1]

.

Psychosis

This will require specialist review and treatment, and may be treated with quetiapine or clozapine. Risperidone and olanzapine should be avoided owing to their potential risk of worsening PD[1]

.

Parkinson’s disease dementia

Pharmacological management of PD dementia may be initiated by a specialist after careful consideration of comorbidities and risk of adverse effects. This may be treated with cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g. rivastigmine) or a glutamate receptor antagonist (e.g. memantine).

There is a risk of cognitive impairment with the use of antimuscarinic medicines (e.g. oxybutynin, amitriptyline or tolterodine), ranitidine and benzodiazepines. These should, therefore, be used with caution[1]

.

Urinary complications

Bladder problems commonly occur in patients with PD, and this group is particularly prone to developing urinary tract infections (UTIs). Therefore, they should be monitored for changes in urinary frequency, urgency and nocturia. Any confirmed UTIs should be treated as per trust antimicrobial guidelines.

Constipation

This can affect the absorption of medicine and, therefore, should be managed using laxatives where necessary. Choice of laxative usually depends on what has caused the constipation, so each patient will likely be different. In addition, simple measures, such as ensuring adequate hydration, can help prevent this complication. Diet and lifestyle advice should also be offered, with patients advised to increase physical activity and intake of fibre and fluids[1]

. Information leaflets and resources with specific guidance on diet and lifestyle for patients with PD are available on the charity Parkinson’s UK’s website

[9]

.

Dysphagia

A speech and language therapist is necessary for managing patients experiencing swallowing difficulties. Depending on the severity of the dysphagia, a nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy may be necessary for feeding and administration of medicine. This may require alteration of medicine formulation or route of administration, and should ideally be reviewed collaboratively by the pharmacist and PD specialist. Online calculators, such as the one produced by Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust’s PD team, may be used for calculating the doses when changing formulations. The pharmacy team should ensure appropriate formulations of medicines are supplied promptly to prevent delays or omission of doses[1],[9],[10]

. More can be found in ‘How to tailor medication formulations for patients with dysphagia’ (Pharm J 2016;297[7892]).

Surgery considerations

Advanced planning is crucial to ensure the management of PD is not compromised. Patients should discuss their upcoming elective surgery with known PD specialists. Emergency surgery patients with PD should be highlighted to the inpatient PD team and considerations should be made between the initial pre-operative and post-operative periods[11]

.

Pre-operative period:

- PD medicines should be given until the start of induction with a sip of fluid (typically patients are nil by mouth at the point of induction, but swallowing PD tablets with a small amount of water is suitable);

- If the surgery is expected to last more than three hours, or if there is likely to be a nil by mouth period for more than six hours, an alternative route of drug administration must be arranged, such as the use of a nasogastric tube or a rotigotine patch, but this may require specialist advice from the PD team if necessary.

Anaesthetic induction:

- General anaesthesia ensures good control of tremor and dyskinesia, but propofol can increase dyskinesia;

- Avoid anticholinergic medicines (e.g. atropine sulfate, hyoscine butylbromide, glycopyrronium bromide) as they can increase saliva viscosity;

- Local anaesthesia allows close monitoring of PD symptoms with the benefit of being able to continue to administer oral medicine, particularly if the patient requires frequent doses of levodopa.

Intra-operative period:

- Avoid centrally-acting anti-emetics which can exacerbate motor symptoms; domperidone is preferred.

Post-operative period:

- As soon as possible, assess the patient’s ability to swallow and revert to oral medicine where possible;

- Consider an alternative route of administration if there is a delay to oral route (e.g. vomiting, worsening dysphagia, delayed gastric emptying, ileus, strict bowel rest or other);

- Be vigilant for post-operative complications, such as delirium, which may be more common in patients with PD. Discuss individual patients with the care of older people or psychiatry liaison team where applicable.

Transfer to primary care

Pharmacists can improve communication between secondary and primary care by sharing the necessary information relating to a patient’s medicine changes:

- Patients should receive a copy of the discharge letter with an accurate and up-to-date list of their medicine on discharge;

- Hospital pharmacists should liaise with community pharmacists regarding changes to medicine, particularly if the patient uses a compliance aid. The GP will receive a copy of the discharge letter;

- The pharmacy team should counsel patients and carers, where necessary, on any medicine changes, and ensure the patient has an adequate supply of all their medicine on discharge[12],[13]

.

Best practice

It is essential to consider the following:

- Do not stop a patients Parkinson’s disease (PD) medicines when they are admitted — convert to alternative formulation or routes if necessary;

- Always give medicine on time — late or missed doses may lead to PD symptom deterioration;

- Determine the appropriateness of self-administration by patient or carer;

- Avoid medicines that will exacerbate PD symptoms (e.g. dopamine blockers, such as metoclopramide or haloperidol);

- Undertake medicines reconciliation within the first 24 hours of admission to hospital;

- Refer all PD patients that are admitted into hospital to the PD nurse specialist to ensure prompt review and management;

- Communicate any PD medicines changes from hospital to the community pharmacist and GP.

Useful resources

- Parkinson’s UK provides multiple resources for professionals, including the Start Parkinson’s foundation modules for pharmacists;

- The Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education’s neurology programme, which was developed for anyone working in community pharmacy;

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s clinical knowledge summary on Parkinson’s disease.

About the author

Maria Nawaz is a specialist pharmacist at North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust. Oyinkansola Close is an urgent care pharmacist at North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust and North East Ambulance Service.

Correspondence to: maria.nawaz@nth.nhs.uk

References

[1] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Parkinson ’s disease in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG71]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG71 (accessed March 2020)

[2] Cheng H, Ulane CM & Burke RE. Clinical progression in Parkinson’s disease and the neurobiology of axons. Ann Neurol 2010;67(6): 715–725. doi: 10.1002/ana.21995.

[3] Parkinson’s UK. The incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s in the UK: Results from the clinical practice research data-link summary report. 2018. Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-01/CS2960%20Incidence%20and%20prevalence%20report%20branding%20summary%20report.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[4] Pang SY, Ho PW, Liu H et al. The interplay of aging, genetics and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Transl Neurodegener 2019;16(8):23. doi: 10.1186/s40035-019-0165-9

[5] de Lau, LM & Breteler, MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2006;5(6):525–535. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9

[6] Low V, Ben-Schlomo Y, Coward E et al. Measuring the burden and mortality of hospitalisation in Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional analysis of the English Hospital Episodes Statistics database 2009–2013. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21(5):449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.01.017

[7] Oguh O & Videnovic A. Inpatient management of Parkinson disease: current challenges and future directions. Neurohospitalist 2012;2(1):28–35. doi: 10.1177/1941874411427734

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. NICE guideline (NG5). 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/chapter/1-Recommendations#medicines-reconciliation (accessed March 2020)

[9] Parkinson’s UK. Information and support. Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/information-and-support (accessed March 2020)

[10] North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust. In-patient management of Parkinson’s disease. 2019. [Internal trust document — unavailable for public access]

[11] Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust. In-patient management of Parkinson’s guideline: Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust. 2018. Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/patient-management-parkinsons-guideline-plymouth-hospitals-nhs-trust (accessed March 2020)

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transition between inpatient hospital settings and community or care home settings for adults with social care needs. NICE guideline (NG27). 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng27 (accessed March 2020)

[13] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Hospital referral to community pharmacy: An innovators’ toolkit to support the NHS in England. 2014. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Support/toolkit/3649—rps—hospital-toolkit-brochure-web.pdf (accessed March 2020)