Science Photo Library

Gonorrhoea is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae (N. gonorrhoeae) that primarily affects the urogenital tract and rectum, as well as extragenital sites, such as the pharynx, endocervix and conjunctiva[1],[2]

.

In 2018, the World Health Organization estimated there were 87 million new cases of gonorrhoea worldwide, with 54,798 new diagnoses made in England and 3,233 in Scotland during the same year[3]

,[4],[5]

. With a 14% decrease (equal to £96m) in total local authority spending on sexual health between 2013 and 2018, coupled with increasing infection and antimicrobial resistance rates, gonorrhoea presents a significant public health challenge for healthcare professionals and policymakers[6]

.

Guidance published by Public Health England (PHE) in 2019 suggested that pharmacists could help alleviate some of the current burdens on the system, because of their accessibility to deprived communities and the trusted relationship they enjoy with the local communities they interact with daily[7]

.

Pharmacies are a source of healthcare advice for patients in the community. Pharmacists can refer patients to sexual health services and are opportunistically able to promote good sexual health practices. Pharmacists are also well trained in identifying a wide range of symptoms and making treatment recommendations, which are covered in this article on gonorrhoea infection.

Epidemiology and transmission

With transmission of gonorrhoea occurring through direct inoculation of infected secretions from one mucous membrane to another, anyone who is sexually active can become infected, but particular risk factors include multiple sexual partners, a current or prior history of STIs and inconsistent condom usage[8]

.

The highest incidence of infection is seen in those aged between 20–24 years, in men who have sex with men (MSM), black ethnic minorities and individuals with increased rates of partner change[9]

. Localised geographical outbreaks can occur, often in urban areas as transmission tends to concentrate within sexual networks[10]

. Relative socioeconomic deprivation has been linked with increased infection rates, the reason for which is likely a mix of factors including education, job security and access to services within these communities[11]

.

Signs and symptoms

Gonorrhoea presents as an uncomplicated infection of the lower genital urethral tract with symptoms following a two to five day incubation period[12],[13]

. Male urethral infection is symptomatic in more than 90% of cases; however, one in ten infected men and almost half of infected women do not experience any symptoms[1],[14]

.

White, yellow or green mucopurulent urethral discharge and pain upon urination (dysuria) are among the more common symptoms in men; however, testicular or rectal pain and epididymitis may also occur[13]

.

Women may present with odourless white, yellow or green vaginal discharge or dysuria. In cervical infection, abnormal uterine bleeding and mucopurulent discharge may be found on examination, as well as pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia)[12]

. Lower abdominal pain and fever may indicate ascending infection, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)[15]

.

The majority of men and women with rectal infections are asymptomatic; however, some may present with anal discharge, pain, discomfort and pruritis[13]

. Pharyngeal infection is predominantly asymptomatic, occasionally presenting with a sore throat[13]

.

Complications

An undiagnosed or untreated infection may result in serious complications and further transmission. In men, infection may lead to epididymo-orchitis and prostatitis. In women, PID and an increased risk of complications during pregnancy, such as ectopic pregnancy, low birth weight and spontaneous preterm birth may occur[16],[17],[18]

. There is also the potential for mother-to-child transmission during vaginal delivery, most commonly resulting in eye infections[19]

, but more rarely causing systemic infections in the newborn[20]

. Infertility as a result of untreated infection can occur in both sexes[21],[22]

. Disseminated gonococcal infection may affect joints causing polyarthralgia and, potentially, septic arthritis[23]

.

Furthermore, cohort studies suggest an increased risk of HIV acquisition in the presence of gonorrhoea infection[24]

. Undiagnosed gonorrhoea may also mean other STIs may not be detected and diagnosed, with studies showing chlamydia co-infection in as many as 40% of cases[25]

.

Opportunities for pharmacy

Requests for over-the-counter (OTC) medicine or emergency contraception present opportunities for pharmacists and pharmacy teams to open a dialogue with patients around sexual health and highlight an important role in prevention. Some pharmacies in Southwark now operate as ‘C-card’ outlets, which means that any young person with a C-card can access condoms, free of charge[26]

.

Opportunities may not always present to the pharmacist directly and, therefore, training of pharmacy teams is especially important.

Some examples of scenarios where there is an opportunity to open a dialogue include:

- Requests for emergency hormonal contraception;

- Purchases of barrier prophylactics — condoms, female condoms and dental dams;

- STI-based consultations (e.g. for those being treated under patient group directions for other STIs);

- Purchases of pregnancy testing kits;

- C-card consultations;

- When seeking advice where a partner has tested positive for an STI.

It is important to approach conversations on sexual health in a sensitive and non-judgemental manner, while being mindful of privacy. Patients will have varying degrees of openness around their sexual health; therefore, making use of the consultation room and obtaining consent prior to questioning around sexual histories may make patients more comfortable. Example phrases include:

- “Is it okay to ask some questions around your sexual history? This is to assess your risk of having acquired an STI.”

- “While you are here, would you like some information on how you can get tested for STIs?”

- “Have you noticed any new symptoms, such as discharge or pain during urination?”

The Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education deliver e-learning programmes on sexual health in the pharmacy, dealing with difficult conversations and consultations skills (cppe.ac.uk/gateway/sexual). The British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) also produce guidance on consultations requiring sexual health histories to guide further learning[27]

.

The identification of patients who may be at risk of infection will allow prompt referral to sexual health services and provide an opportunity to promote good sexual health practices, such as:

- Consistent use of barrier contraceptives for STI prevention, such as condoms (including female condoms) and dental dams;

- Regular STI testing when sexually active, particularly with new and changing partners;

- The early signs and symptoms of STIs, such as discharge or dysuria.

Diagnosis

Testing of gonorrhoea usually takes place in sexual health clinics, either as part of an asymptomatic or symptomatic sexual health screen or as a result of contact tracing. Specimens are usually self-collected with urine samples, as well as penile-urethral, vulvo-vaginal, rectal and pharyngeal swabs. The choice of sample site depends on the type of sexual activity and/or clinical symptoms (e.g. a rectal and pharyngeal sample should be tested for all MSM)[13]

.

A formal diagnosis is made if N. gonorrhoeae is detected in a sample taken from an infected site using either a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) or microbiological culture. NAATs are widely available and, therefore, form the primary method of diagnosis, replacing culture and microscopy. NAATs identify N. gonorrhoeae with high sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (>90%) but may not produce accurate results in the two-week ‘window period’ following exposure. Therefore, those who test negative within two weeks of sexual contact with a positive partner should repeat the test[28]

.

Microbiological culture of N. gonorrhoeae is mainly used to determine antimicrobial susceptibility, the importance of which is increasing in practice owing to emerging gonococcal resistance to antimicrobials. Gonococcal resistance is monitored through the gonococcal resistance to antimicrobials surveillance programme (GRASP) by PHE in England and Wales[29]

.

Treatment

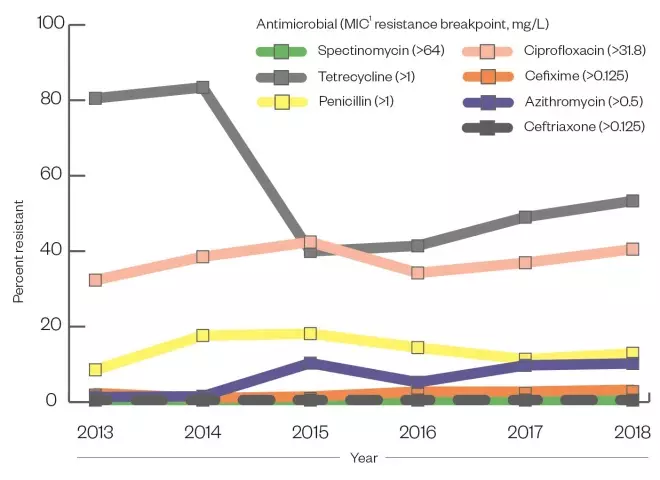

Clearance of gonorrhoea infection can often be achieved with a single dose of a sensitive antibiotic agent. However, extensive antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to all antimicrobial classes used to treat the infection at scale has been observed in recent years. N. Gonorrhoeae is especially adept in generating AMR and does so using multiple mechanisms, including the transfer of genetic material between cells. Given that many infections are asymptomatic, unrestricted access to or misuse of antibiotics may drive resistance, resulting in the need for updated national guidelines and the ongoing surveillance effort by PHE (see Figure)[30],[34]

.

Treatment guidelines for the UK produced by BASHH advise on the choice of agent and were recently revised in 2018, reflecting national changes in antimicrobial susceptibility[13]

. Regardless of the agent selected for treatment, patients should be advised to abstain from sexual intercourse during treatment and for at least seven days after completion of the course.

Figure: Percentage of gonococcal isolates resistant to selected antimicrobials

- The use of benzathine and procaine penicillin between the 1940s and 1970s led to a high level of penicillin resistance by the 1980s;

- Tetracycline resistance in the UK was reported in 37% of cases by the 2000s;

- Ciprofloxacin resistance was described at 22% in 2005;

- Azithromycin resistance was observed in 9.8% of isolates sent to Public Health England in 2018.

Key: 1 = minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

Sources: Whittles LK, White PJ, Paul J & Didelot X[30], Public Health England[34]

Ceftriaxone

Indication

A single intramuscular (IM) dose of 1g ceftriaxone is recommended as the first-line treatment for anogenital and pharyngeal infection, where prior antimicrobial susceptibility is unavailable[13]

.

Safety and other considerations

Common side effects include gastrointestinal (GI) upset and local skin reactions[31]

.

As with other cephalosporins, cross-reactivity in a small number of penicillin-allergic patients is an issue; however, this occurs predominantly with first-generation cephalosporins[31]

. Ceftriaxone may potentiate the activity of anticoagulants, such as warfarin and acenocoumarol, increasing the international normalised ratio (INR), particularly in older patients[32],[33]

. Additional monitoring of INR or alternative treatments may be indicated in these patients.

Resistance

Ceftriaxone resistance remains low in England and Wales, with no resistant isolates detected by GRASP in 2018[34]

. However, an 8% rise in the proportion of cases with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) (i.e. the lowest concentration of drug that will inhibit visible growth) greater than 0.03mg/L between 2017 and 2018 suggested an increasing proportion of strains with reduced susceptibility[34]

. In response, BASHH increased the advised dose of ceftriaxone from a single 500mg IM injection to a 1g IM injection[13]

. Previously, dual therapy with ceftriaxone 500mg IM injection and azithromycin 1g IM injection was used as first-line treatment. However, increased prevalence of azithromycin-resistant gonorrhoea (9.7% in 2018) (see Figure), combined with concerns of growing macrolide resistance in other STIs, such as

Mycoplasma genitalium infection, meant this strategy is no longer recommended[13]

.

More recently, PHE reported the diagnosis of two cases of gonorrhoea resistant to ceftriaxone and azithromycin in 2019[35]

. Both cases were successfully treated, and sexual contact tracing and follow-up was required to minimise the risk of onward transmission.

Ciprofloxacin

Indication

When antimicrobial susceptibility is known and is sensitive, a single oral 500mg dose of ciprofloxacin is the first-line treatment. This strategy aims to delay the emergence of ceftriaxone resistance by reducing the selective pressure from using ceftriaxone as monotherapy.

Safety and other considerations

The potential side effects related to the use of fluoroquinolones limit their use in some patients. Pregnant women should not be managed with ciprofloxacin owing to the association between quinolones and cartilage toxicity (as demonstrated in animal studies)[36]

. QT interval prolongation is also associated with their use, requiring caution in those with existing arrhythmias or taking concurrent QT-prolonging medicines, such as macrolides and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors[31],[36],[37]

. Tendonitis and tendon rupture have been observed within 48 hours of commencing treatment, as well as potentially irreversible peripheral neuropathies[38]

. A 2018 study aimed to measure the risk of tendon rupture with fluoroquinolones, estimating an addition of 2.9 tendon ruptures per 10,000 patients per year. This figure increased to 5.6 ruptures in patients aged over 60 years[39]

. Furthermore, case reports have suggested that fluoroquinolones may reduce the seizure threshold in patients predisposed to seizures; however, this association is debated[40],[41],[42]

.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) released guidance in 2018 and 2019 recommending restricted use of fluoroquinolones in patients aged over 60 years and those with concurrent kidney disease, among others[43]

. While there are documented risks, they must be weighed against the benefits of treating the infection with a single dose of a susceptible agent.

Resistance

There is widespread resistance to ciprofloxacin in England and Wales. In 2018, 40% of gonorrhoea isolates analysed by GRASP were resistant, an increase of 6.2% since 2016[34]

. For this reason, ciprofloxacin is only used when sensitivity can be guaranteed.

Alternative regimens

When first-line treatments are contraindicated or impractical, such as for those with true penicillin allergy, the use of alternative agents is advised (see Box). Caution must be exercised in patients with pharyngeal infection, where increased rates of treatment failure have been observed with the use of alternatives, such as monotherapy. Dual therapy with azithromycin is therefore encouraged[44],[45]

.

Box. Alternative regimens for the treatment of gonorrhoea[13], [31]

- A single dose cefixime 400mg orally, plus azithromycin 2g orally, can be used where an intramuscular injection is contraindicated or impractical;

- A single dose of gentamicin 240mg intramuscularly, plus azithromycin 2g orally, can be used as an alternative in patients with allergies to cephalosporins or penicillin allergy with a history of cross-sensitivity to cephalosporins;

- A single intramuscular dose of spectinomycin 2g, plus azithromycin 2g orally, can be given, although this regimen is less effective in pharyngeal infection. Supplies for spectinomycin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic that is unlicensed in the UK, are imported from overseas and can be difficult to obtain at times.

Follow-up and partner notification

Clearance of the infection is confirmed via test of cure (TOC), which is advised for all patients, especially where there is a high rate of treatment failure, or in patients showing persistent signs of infection after treatment[13]

. TOC can be performed by repeating the NAAT at least 7–14 days post treatment; culture and sensitivity at this point can also guide treatment options if first-line treatment fails.

Partner notification is the process of advising previous sexual partners of individuals diagnosed with STIs on accessing testing and treatment. The aim is to break the chain of infection and reinfection within sexual networks. Sexual healthcare assistants obtain a detailed sexual history and then either support the patient in contacting previous partners or do so on their behalf via text message, phone or in person. Pharmacy teams should be aware of the practice of partner notification (as it is not normally undertaken in a community pharmacy) and relay its importance to patients[46]

.

Useful resources

Guidelines:

- British Association for Sexual Health and HIV

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence — Clinical Knowledge Summaries

Resources for practising safe sex:

E-learning:

References

[1] Sherrard J & Barlow D. Gonorrhoea in men: clinical and diagnostic aspects. Genitourin Med 1996;72(6):422–426. doi: 10.1136/sti.72.6.42

[2] Barlow D & Phillips I. Gonorrhoea in women: diagnostic, clinical, and laboratory aspects. Lancet 1978;311(8067):761–764. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90870-X

[3] World Health Organisation. Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance. 2018. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/stis-surveillance-2018/en/ (accessed September 2020)

[4] Public Health England. Gonorrhoea diagnostic rate/100,000. 2018. Sexual and Reproductive Health Profiles. Available at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/sexualhealth/data#page/3/gid/8000035/pat/42/par/R3/ati/104/are/E45000001/iid/90759/age/1/sex/4/cid/4/page-options/ovw-tdo-0_car-ao-1_car-do-0 (accessed September 2020)

[5] Cameron RL, Cullen BL, Wallace LA et al. Health Protection Scotland Surveillance Report. Genital chlamydia and gonorrhoea infection in Scotland: laboratory diagnoses 2009–2018. 2019. Available at: https://hpspubsrepo.blob.core.windows.net/hps-website/nss/2791/documents/1_genital-chlamydia-gonorrhoea-scotland-2009-2018.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[6] Robertson R. Sexual health services and the importance of prevention. The King’s Fund. 2018. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2018/12/sexual-health-services-and-importance-prevention (accessed September 2020)

[7] Public Health England. The pharmacy offer for sexual health, reproductive health and HIV. A resource for commissioners and providers. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pharmacy-offer-for-sexual-health-reproductive-health-and-hiv (accessed September 2020)

[8] Morris S. Gonorrhoea infection: symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. BMJ Best Practic e 2020. Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/51?q=Gonorrhoea%20infection&c=suggested (accessed September 2020)

[9] Public Health England. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): annual data tables. Table 2: New STI diagnoses & rates by gender, sexual risk, age group & ethnic group, 2014–2018. 2010. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-annual-data-tables (accessed September 2020)

[10] O’Brien A, Sherrard-Smith E, Sile B et al. Spatial clusters of gonorrhoea in England with particular reference to the outcome of partner notification: 2012 and 2013. PLoS ONE 2018;13(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195178

[11] Furegato M, Chen Y, Mohammed H et al. Examining the role of socioeconomic deprivation in ethnic differences in sexually transmitted infection diagnosis rates in England: evidence from surveillance data. Epidemiology and Infection 2016;144(15):3253–3262. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816001679

[12] Lewis DA, Bond M, Butt KD et al. A one-year survey of gonococcal infection seen in the genitourinary medicine department of a London district general hospital, 1999. Int J STD AIDS 1999;10(9):588–594. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914717

[13] Fifer H, Saunders J, Soni S et al. 2018 UK national guideline for the management of infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Int J STD AIDS 2019;31(1):4–15. doi: 10.1177/0956462419886775

[14] NHS. Gonorrhoea overview. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/gonorrhoea (accessed September 2020)

[15] Pattman R, Sankar N, Elawad B et al. Oxford Handbook of Genitourinary Medicine, HIV, and Sexual Health Oxford University Press; 2010.

[16] Liu B, Roberts CL, Clarke M et al. Chlamydia and gonorrhoea infections and the risk of adverse obstetric outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89(8):672–678. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051118

[17] Reekie J, Donovan B, Guy R et al. Risk of ectopic pregnancy and tubal infertility following gonorrhea and chlamydia infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019;69(9):1621–1623. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz145

[18] Chen JZ, Gratrix J, Brandley J et al. Retrospective review of gonococcal and chlamydial cases of epididymitis at 2 Canadian sexually transmitted infection clinics, 2004–2014. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2017;44(6):359–361. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000602

[19] Laga M, Meheus A & Piot P. Epidemiology and control of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1989;67(5):471–477. PMID: 2611972

[20] Woods CR. Gonococcal infections in neonates and young children. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases 2005;16(4):258–270. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2005.06.006

[21] Tsevat DG, Wiesenfeld HC, Parks C & Peipert JF. Sexually transmitted diseases and infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.008

[22] Fode M, Fusco F, Lipshultz L & Weidner W. Sexually transmitted disease and male infertility: a systematic review.Eur Urol Focus 2016;2(4):383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2016.08.002

[23] Bardin T. Gonococcal arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003;17(2):201–208. doi: 10.1016/S1521-6942(02)00125-0

[24] Ward H & Minttu R. The contribution of STIs to the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AID S 2010;5(4):305–310. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a8844

[25] Creighton S, Tenant-Flowers M & Taylor CB. Co-infection with gonorrhoea and chlamydia: how much is there and what does it mean? Int J STD AIDS 2003;14(2):109–113. doi: 10.1258/095646203321156872

[26] Tatum M. How pharmacy is helping to contain the resurgence of gonorrhoea and syphilis. Pharm J 2019;303;online. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2019.20207139

[27] Brook G, Church H, Evans C et al. UK National Guideline for consultations requiring sexual history taking, 2019. British Association Sexual Health and HIV. Available at: https://www.bashhguidelines.org/current-guidelines/sexual-history-taking-and-sti-testing/sexual-history-taking-2019/ (accessed September 2020)

[28] Public Health England. Guidance for the detection of gonorrhoea in England including guidance on the use of dual nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for chlamydia and gonorrhoea. 2015. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/769003/170215_Gonorrhoea_testing_guidance_REVISED__2_.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[29] Public Health England. Gonococcal resistance to antimicrobials surveillance programme report. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gonococcal-resistance-to-antimicrobials-surveillance-programme-grasp-report (accessed September 2020)

[30] Whittles LK, White PJ, Paul J & Didelot X. Epidemiological trends of antibiotic resistant gonorrhoea in the United Kingdom. Antibiotics 2018;7(3). doi: 10.3390/ antibiotics7030060 (accessed September 2020)

[31] BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online). Available at: http://www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed September 2020)

[32] Saum LM & Balmat RP. Ceftriaxone potentiates warfarin activity greater than other antibiotics in the treatment of urinary tract infections. J Pharm Pract 2016;29(2):121–124. doi: 10.1177/0897190014544798

[33] EMC. Ceftriaxone 1g powder for solution for injection or infusion: summary of product characteristics (SmPC). Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10604/smpc (accessed September 2020)

[34] Public Health England. Key findings from the Gonococcal Resistance to Antimicrobials Surveillance Programme (GRASP 2018). 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/834924/GRASP__2018_report.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[35] Public Health England. Two cases of resistant gonorrhoea diagnosed in the UK. Public Health England. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/two-cases-of-resistant-gonorrhoea-diagnosed-in-the-uk (accessed September 2020)

[36] EMC. Ciproxin 500 mg film-coated tablets: summary of product characteristics. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6153/smpc (accessed September 2020)

[37] Gorelik E, Masarwa R, Perlman A et al. Fluoroquinolones and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review, meta-analysis and network meta-analysis.Drug Safety 2019;42(4):529–538. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0751-2

[38] Morales D, Pacurariu A, Slattery J et al. Association between peripheral neuropathy and exposure to oral fluoroquinolone or amoxicillin-clavulanate therapy. JAMA Neurology 2019;76(7):827–833. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0887

[39] Morales DR, Slattery J, Pacurariu A et al. Relative and absolute risk of tendon rupture with fluoroquinolone and concomitant fluoroquinolone/corticosteroid therapy: population-based nested case-control study. Clinical Drug Investigation 2019;39(2):205–213. doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0729-y

[40] Tattevin P, Messiaen T, Pras V et al. Confusion and general seizures following ciprofloxacin administration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998;13(10):2712–2713. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.10.2712

[41] Kushner JM, Peckman HJ & Snyder CR. Seizures associated with fluoroquinolones. Ann Pharmacother 2001;35(10):1194–1198. doi: 10.1345/aph.10359

[42] Chui CSL, Chan EW, Wong AYSet al. Association between oral fluoroquinolones and seizures. Neurology 2016;86(18):1708. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002633

[43] European Medicines Agency. Disabling and potentially permanent side effects lead to suspension or restrictions of quinolone and fluoroquinolone antibiotics. 2019. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/quinolone-fluoroquinolone-containing-medicinal-products (accessed September 2020)

[44] Kirkcaldy RD & Workowski KA. Gentamicin as an alternative treatment for gonorrhoea. Lancet 2019;393(10190):2474–2475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30244-2

[45] Barbee LA, Kerani RP, Dombrowski JC et al. A retrospective comparative study of 2-drug oral and intramuscular cephalosporin treatment regimens for pharyngeal gonorrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56(11):1539–1545. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit084

[46] McClean H, Radcliffe K, Sullivan A & Ahmed-Jushuf I. 2012 BASHH statement on partner notification for sexually transmissible infections. Int J STD AIDS 2013;24(4):253–261. doi: 10.1177/0956462412472804