ZEPHYR/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Differentiate the types of bladder cancer;

- Understand the treatment options for the most common forms of bladder cancer (transitional cell carcinoma/urothelial cancer);

- Be able to recognise common treatment side effects;

- Understand the role of pharmacists in bladder cancer management.

Bladder cancer (BC) occurs when there is growth of abnormal tissue, known as a tumour, in the bladder lining. In some cases, the tumour spreads into the bladder muscle and can metastasise to distant parts of the body. There are around 10,000 new cases of BC each year in the UK (see Figure 1), which makes it the 11th most common cancer, accounting for 3% of all new cancer cases[1–3].

The incidence of BC has decreased in the UK since the early 1990s by 41% in females and 47% in males, and it has decreased across the board by 16% between 2006–2008 and 2016–2018 and is anticipated to continue to decrease by a further 34% by 2035 (13 cases per 100,000 people)[1].

Risk factors

Advanced age is the biggest risk factor for BC, with the highest incidence in those aged 85–89 years, and around 56% of all new cases are diagnosed in people aged over 75 years[1]. Data also show that BC affects twice as many males as females: 1 in 50 males and 1 in 133 females in the UK will be diagnosed with BC in their lifetime. It is also more common in white people than African, Caribbean or Asian people[1].

A person’s risk of developing BC depends on many factors, including age, genetics and exposure to risk factors, including some avoidable lifestyle factors (see Figure 2). It is estimated that 49% of cases are preventable[1].

Compared with the general population, BC risk is 1.8 times higher in people with a first degree relative who has the disease[1,4]. Around 980 cases of BC each year in England are linked with deprivation, with deaths more common in the most deprived areas.

Smoking has been shown to triple the risk of BC compared to non-smokers and the risk in former smokers remains elevated for many years after quitting, even for people with moderate smoking histories[5,6]. Pharmacy teams should enquire on the smoking status of patients and offer them support and advice to support cessation and may find the resource ‘Pharmacy guide to smoking cessation consultations’ useful[7].

Chronic inflammatory processes, such as bacterial infections, parasite infestation, having chronic indwelling catheters, or long-term use of cyclophosphamide, result in increased cellular proliferation and increase the risk of developing BC[8].

The spectrum of BC is diverse; however, urothelial cancers (UC) are the most common and make up 90% of all BC[9]. UC is derived from the cells of the bladder lining (urothelium) called transitional or urothelial cells that stretch from the bladder to the ureter, renal pelvis and renal collecting tubules[10]. Transitional cells come into contact with waste products in the urine that may cause cancer (e.g. chemicals from cigarette smoke or chemical industry). These chemicals increase the risk of BC by up to 50-fold, generating genetic mutations that cause the cells to change their behaviour and invade the basement membrane lying below the transitional layer (sometimes called transitional cell carcinoma [TCC] or UC)[9].

Cancer genomics

Around 58 genes have been identified in causing UC. High mutation burden can be of prognostic and predictive value in the era of immune checkpoint inhibition[11].

The mRNA expression pattern can subdivide UC into distinct molecular subtypes, the simplest molecular classification results in luminal and basal or squamous subtypes, in addition to the neuronal subtype[12].

Luminal UC tends to have a relatively good prognosis and responds better to chemotherapy. However, neuroendocrine differentiation is less common, but is a more aggressive disease with high mutational burden[13].

Certain gene expressions can make the cancer either sensitive or resistant to drug treatment. Some mutations can make BC more sensitive (such as ERBB2) or resistant to cisplatin[9,14–16]. Some are enriched with programmed death 1 (PD-L1) T cells and are sensitive to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), such as atezolizumab, pembrolizumab or avelumab[16,17].

UC may also express activating FGFR3 mutations with activating ERBB2 and ERBB3 mutations allowing FGFR and ERBB drug targeting[17].

UC can also enriched with epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) possibly susceptible to small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. erdafitinib) and novel drugs that target hypoxia-inducible factor 1[11,16].

Symptoms

Haematuria, either microscopic or grossly visible blood in the urine, is the most common presenting symptom of UC. It is usually intermittent, painless and presents throughout micturition. The likelihood of cancer increases when haematuria is visible (macroscopic) rather than microscopic (10–20% versus 2–5%, respectively)[8].

Other symptoms can include:

- Pain (e.g. flank, suprapubic or abdominal pain);

- Changes in daytime or nocturnal frequency, dysuria and urge incontinence (which can be signs of carcinoma in situ of the bladder);

- Fatigue, weight loss and anorexia (usually signs of advanced or/metastatic disease)[18].

As patients may present to community pharmacy with any of these symptoms, pharmacy teams should be aware of the ‘red flag’ symptoms requiring urgent referral and ensure patients consult with their GP to ensure the target to get these symptoms reviewed by a specialist within two weeks is met[19].

Diagnosis

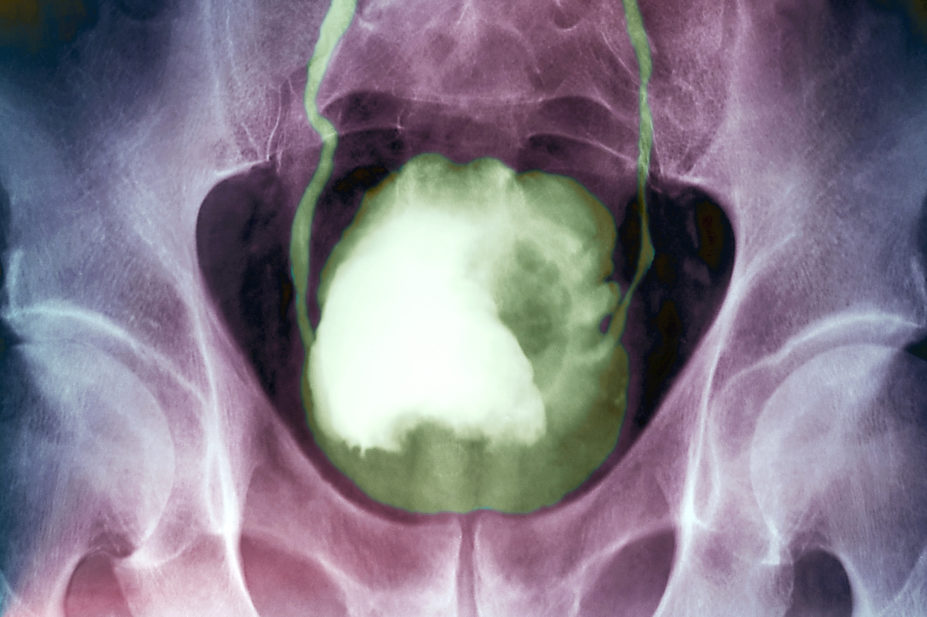

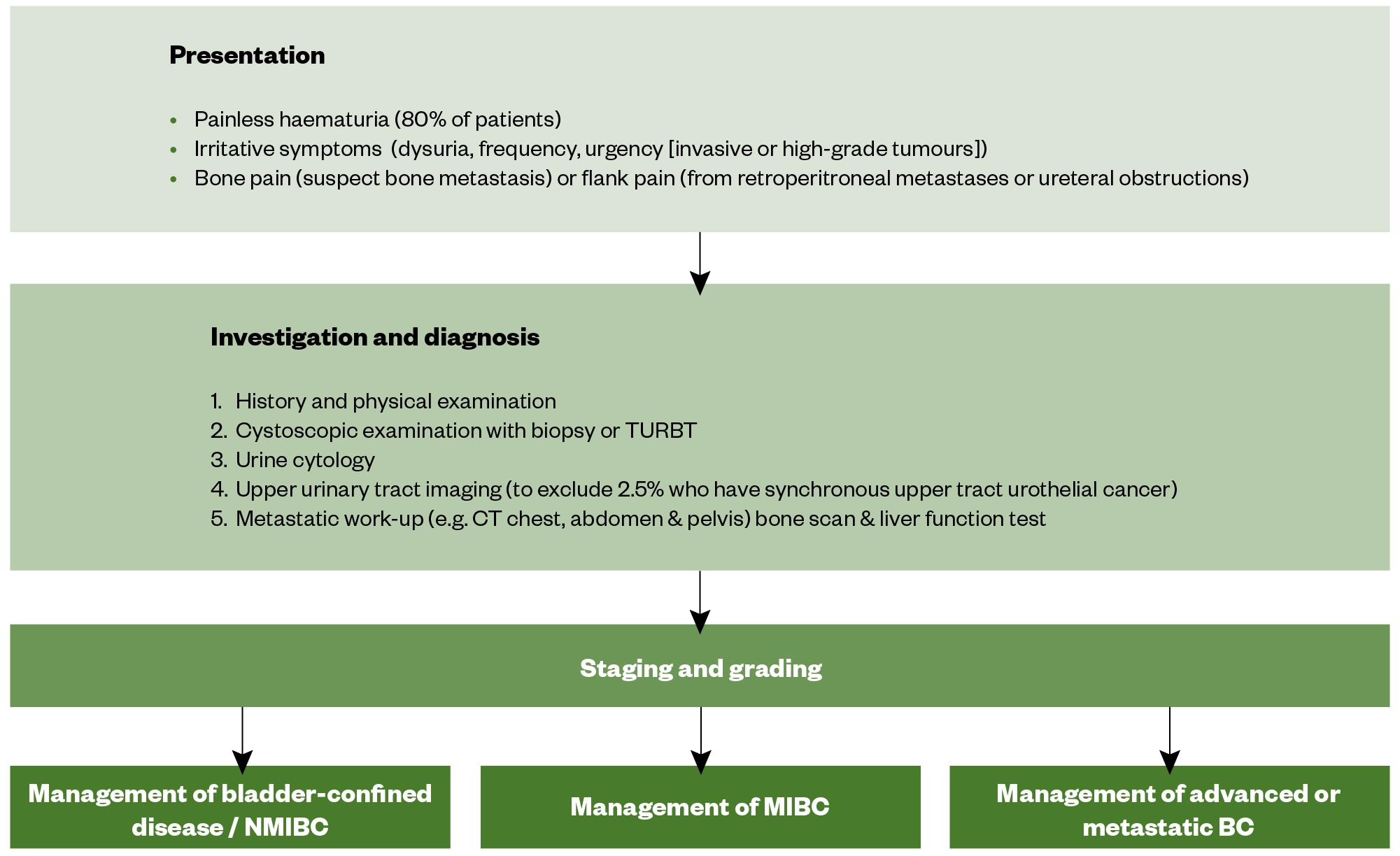

Figure 3 outlines the diagnostic work-up for a patient with suspected BC[2].

While ultrasonography can identify a mass in the bladder, diagnosis requires cystoscopic examination of the bladder and histological evaluation of the tissue either by biopsy or transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT) (see Figure 4)[2]. Complete resection of all tumour tissue should be achieved when possible[2].

Sources: Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support

Presentation

BC can present as:

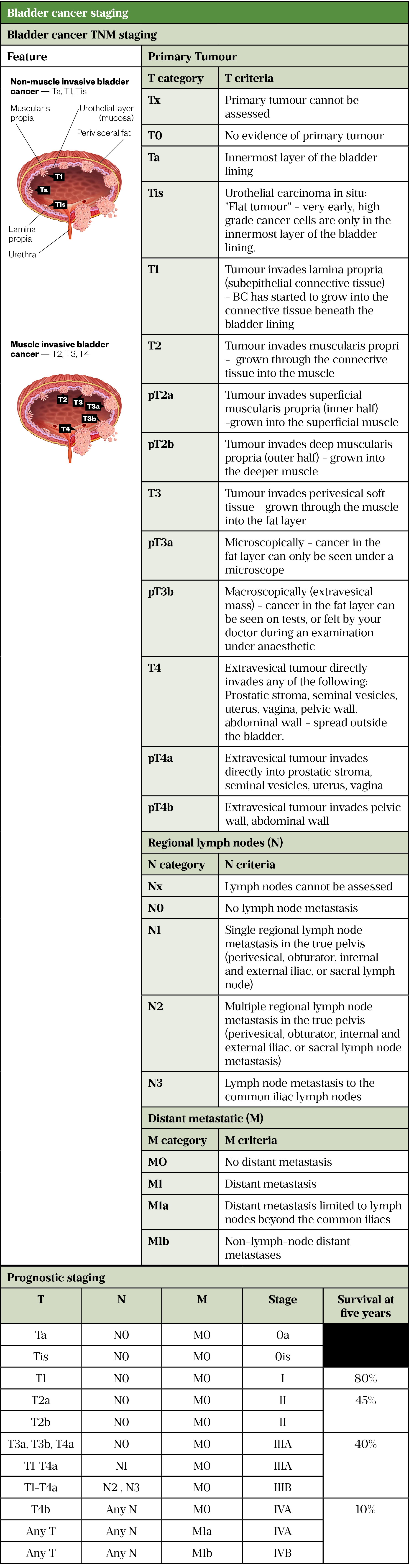

- Early (superficial) cancers (non-muscle invasive bladder cancers [NMIBC]) that have not invaded the deeper layers of the bladder. Around 75% of BC presents as NMIBC, which includes stages pTa-pT1, pTis (see Table 1)[5]. Most patients with MIBC (pT2a-pT4b) are diagnosed with primary invasive BC, but up to 15% have a previous history of NMIBC, almost exclusively high-risk NMIBC[5];

- Those that have invaded deeper (muscle invasive bladder cancers [MIBC]) or;

- Metastatic disease where the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as lungs, liver, lymph nodes in pelvis/abdomen or bones[22].

The pathological findings of a biopsy dictate the approach to management depending on the histology, grade and depth of invasion into the bladder wall (see Table 1)[13,23–26].

If muscle invasion has been confirmed, regional and distant staging should be carried out with further imaging studies, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis, with CT of the chest[2].

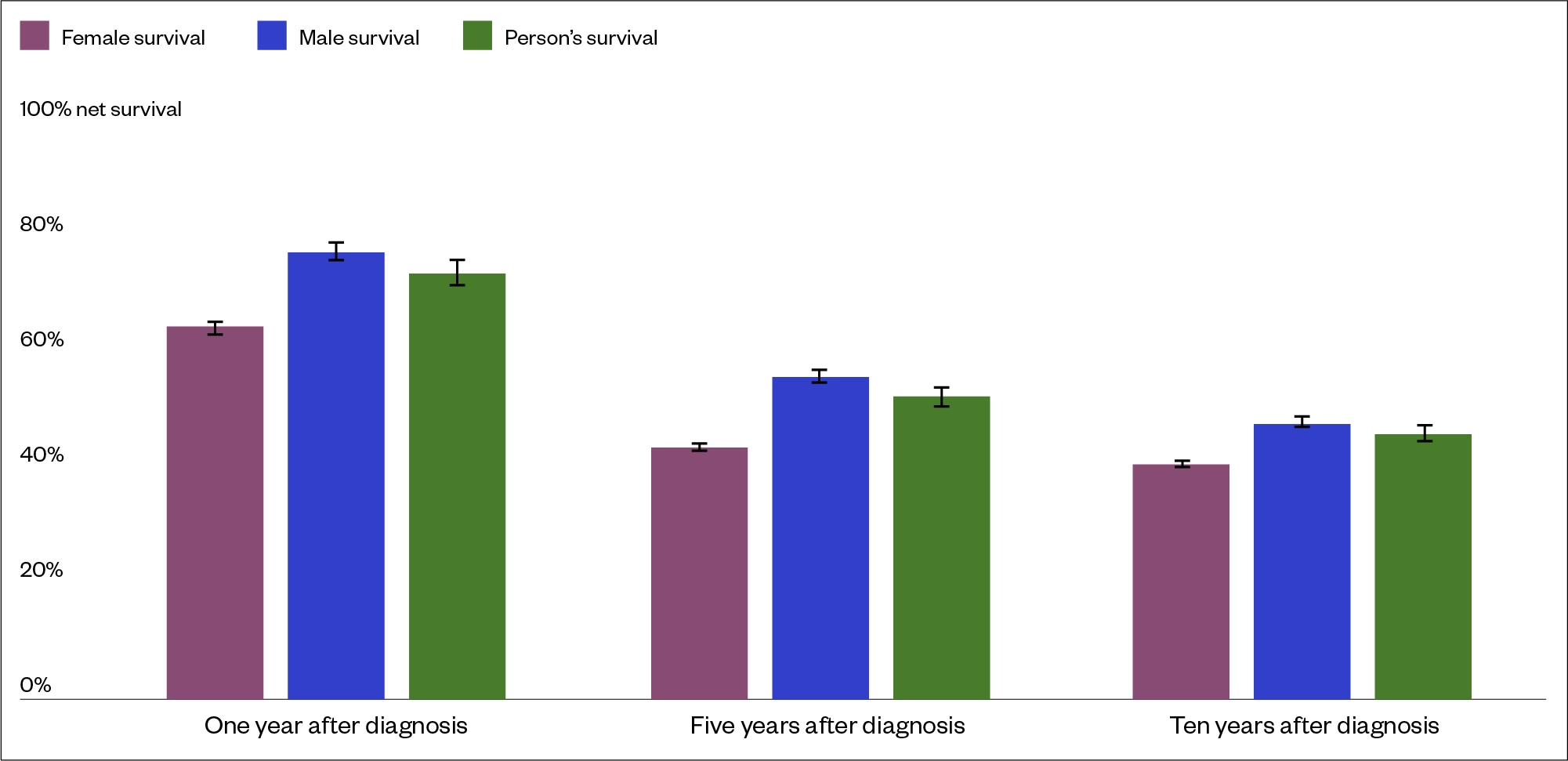

Survival

Survival rates at one, five and ten years for patients in England post-diagnosis of BC between 2013 and 2017 are shown in Figure 5[3,15].

Survival decreases with more extensive disease and ranges from 96% five-year survival for cancer in situ to 6% only when distant metastases are present[26,27].

Management

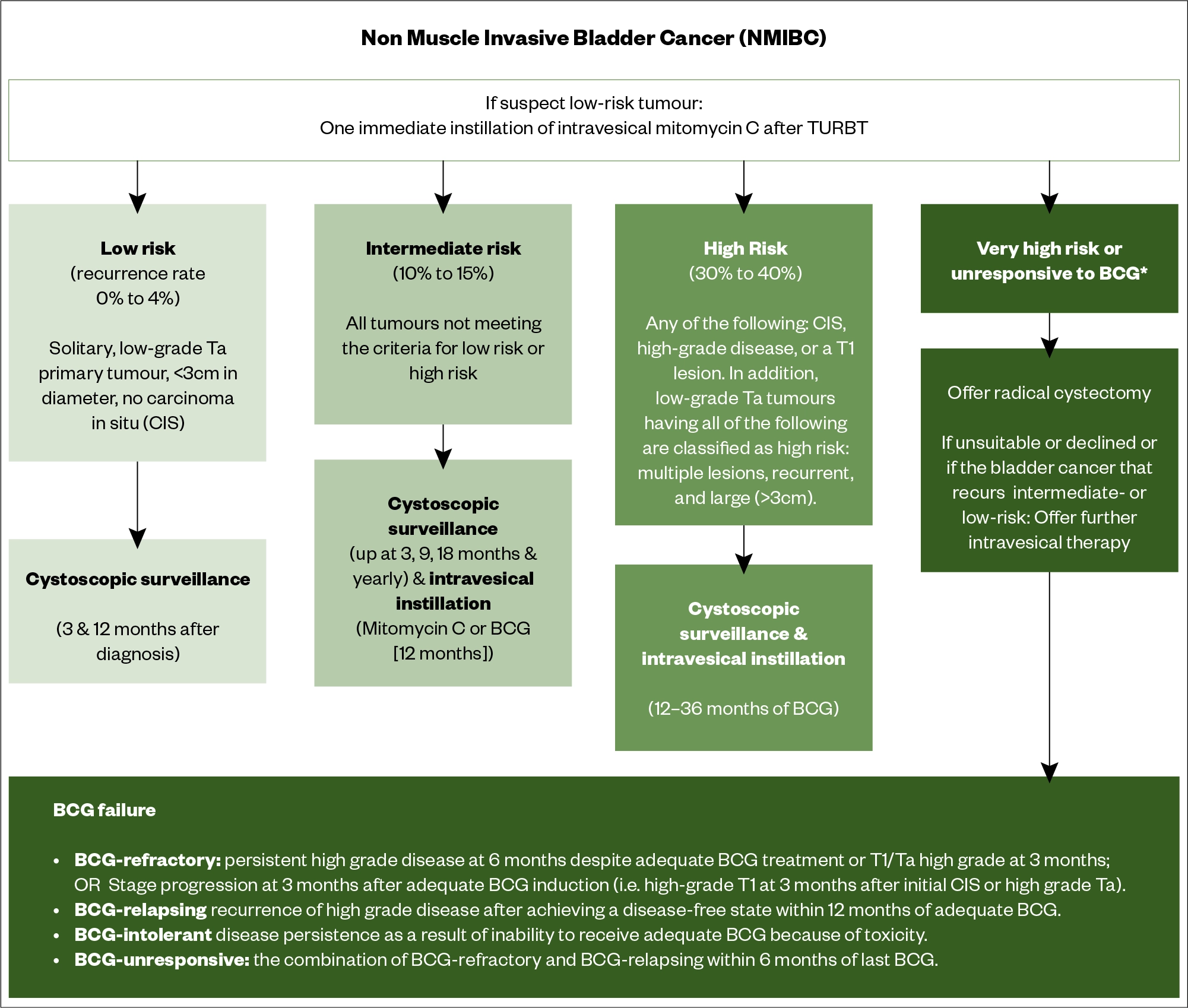

Bladder confined disease or non-muscle invasive bladder cancers

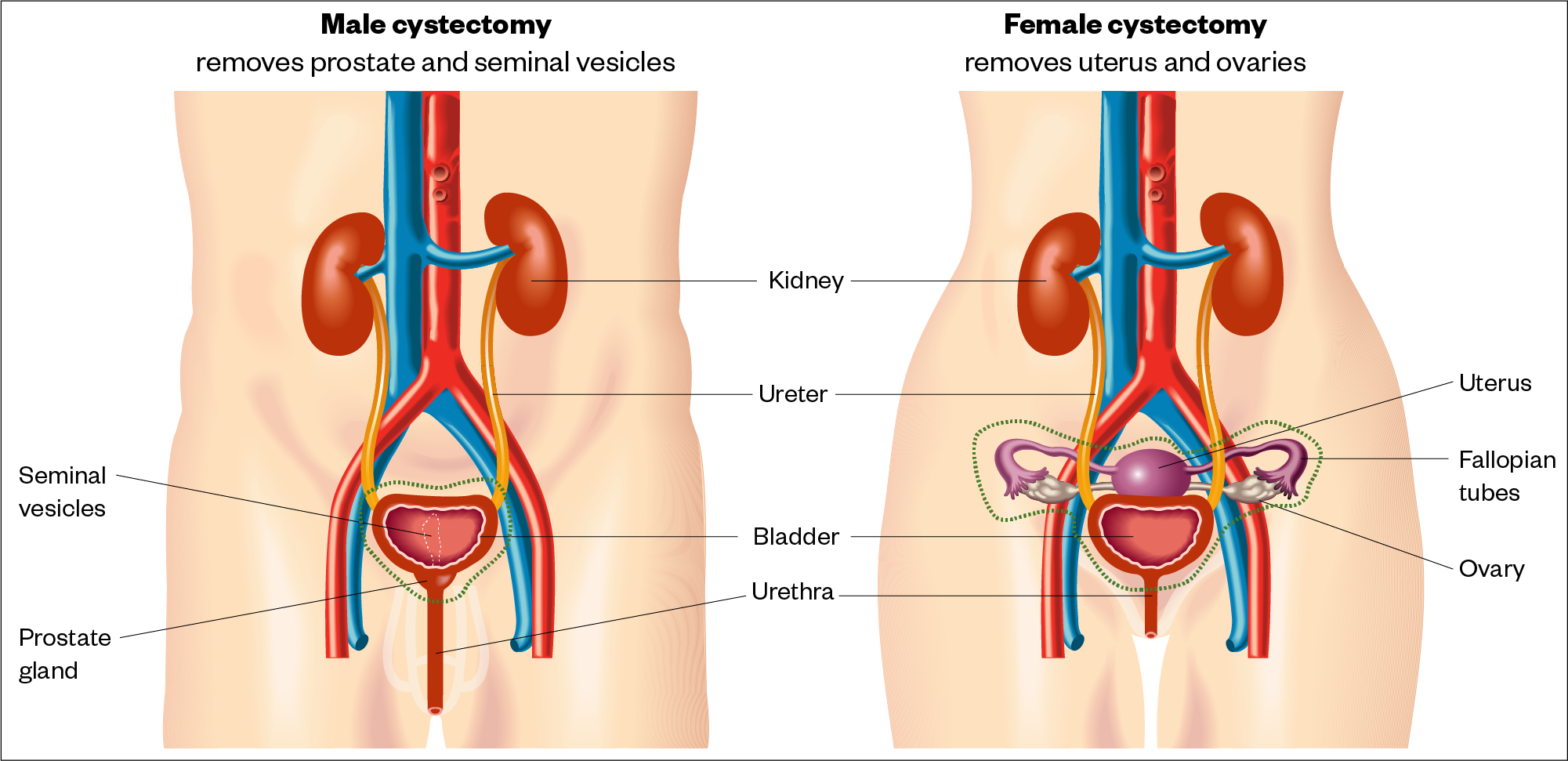

Optimal management of NMIBC requires the complete removal of all visible lesions, followed by intravesical (directly into the bladder) instillations or radical cystectomy (see Figure 6)[2].

Sources: Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support

Conservative management may allow preservation of a functional bladder based upon TURBT, potentially combined with adjuvant intravesical therapy (see Figure 4). Intravesical therapy is recommended (either with mitomycin C or bacillus Calmette-Guérin [BCG]) to decrease the risk of recurrence or progression to MIBC leading to cystectomy. Intravesical therapy permits high local concentrations of adjuvant within the bladder, potentially destroying viable tumour cells that remain following TURBT.

In NMIBC, the risk of recurrence and/or disseminated disease after initial treatment is used to guide therapy. Risk stratification is based upon the European Association of Urologists (EAU) guidelines[30]. Risk of progression is stratified based upon tumour grade, invasion into the lamina propria, tumour size, and whether the tumour is recurrent and multifocal. This involves the staging of the BC (see Table 1). Patients are defined as ‘low’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘high’ risk (see Figure 7)[30].

Some patients with clinical features suggestive of high risk for progression may have indications for initial cystectomy (e.g. unresponsive to BCG)[31].

Low-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

Usually managed by TURBT alone plus a single dose of perioperative intravesical mitomycin C[33]. In a 2007 meta-analysis of two randomised trials, single-dose, post-operative instillation of chemotherapy reduced early tumour recurrence rates by 17% compared with TURBT alone[33]. A randomised trial in 2,243 patients compared mitomycin instillation within 24 hours versus at two weeks and demonstrated definitively that early administration is more effective[34]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends cystoscopic follow-up of patients 3 months and 12 months after diagnosis[35].

Intermediate risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

BCG, a live attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, and mitomycin C are widely used as an intravesical agent.

NICE recommends a course of at least six doses of intravesical mitomycin C. Patients should be offered cystoscopic follow up at 3, 9 and 18 months, and once a year thereafter[35]. The activity of mitomycin with extended maintenance therapy was illustrated in a multicentre trial in which 495 patients were randomly assigned to intravesical therapy with BCG (weekly for six doses), mitomycin (20mg weekly for six weeks), or mitomycin (20mg weekly for six weeks, then maintenance [monthly] for three years). The three-year recurrence-free rates with six-week courses of either BCG or mitomycin were inferior to that achieved with maintenance mitomycin (66 and 69% versus 86%)[36].

In addition to intravesical mitomycin C, European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend BCG and state patients should receive “12 months of BCG instillation therapy (induction therapy with six BCG instillations at weekly intervals), followed by maintenance therapy with three BCG instillations each at 3, 6 and 12 months after the start of the induction cycle”[2].

Other intravesical agents have been compared with BCG, but most are inferior or have not consistently proved to be superior.

A meta-analysis comparing BCG to intravesical chemotherapy showed 68.1% of patients had a complete response with BCG compared to 51.1% on chemotherapy. After 3.6 years, 46.7% of patients on BCG had no evidence of disease compared to 26.2% who had received chemotherapy[37].

High-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

NICE and ESMO recommend that another TURBT should be offered as soon as possible and no later than six weeks after the first resection owing to a significant risk of residual disease[2,35,38]. ESMO recommends full-dose intravesical BCG for one to three years (at least 1 year) with three-year maintenance is more effective than 1-year to prevent recurrences[2,39]. Induction consists of weekly instillations for 6 weeks while maintenance consists of weekly instillations for 3 weeks and then, instillations at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months[2]. The three-year maintenance BCG schedule significantly reduces the risk or recurrence compared with one-year maintenance (hazard ratio [HR] for one versus three years: 1.61; 95% CI: 1.13-2.30; P=0.01). This benefit of three-year therapy does not occur for patients with intermediate-risk tumours[39].

NICE recommends that people with high-risk NMIBC undergo regular cystoscopic follow-up[35].

Up to 85% of patients may experience minor non-infectious symptoms including fever, malaise and bladder irritation (urination frequency, dysuria, or mild haematuria) within a few hours of BCG administration[40,41].

Treatment after bacillus Calmette-Guérin failure

Up to 40% of patients with NMIBC will fail intravesical BCG therapy and there is subsequent recurrence or progression. Stratification of these patients can identify those with a better or worse prognosis[42,43].

Radical cystectomy should be offered first, with further intravesical therapy offered if radical cystectomy is unsuitable or declined by the patient, or if the BC that recurs is intermediate or low risk[35].

Pembrolizumab has been approved by the FDA for BCG-unresponsive, high risk, NMIBC with CIS, with or without papillary tumours, who are ineligible for or have elected not to undergo cystectomy following publication of KEYNOTE-057[44,45]. KEYNOTE-057 was an open-label, single arm, phase II study that showed a complete response rate of 41% with a median duration of response of 16.2 months. However, it is not currently approved for use in the UK[44,45].

Muscle invasive bladder cancers

The treatment of both MIBC and metastatic UC (outlined below) involve systemic drug treatments (e.g. cisplatin or carboplatin-based regimen or immune checkpoint inhibitors).

Optimal management of MIBC involves complete removal of all lesions to decrease the risk of recurrence or progression to metastatic disease (see Figure 8)[2].

Platinum eligibility (cisplatin or carboplatin)

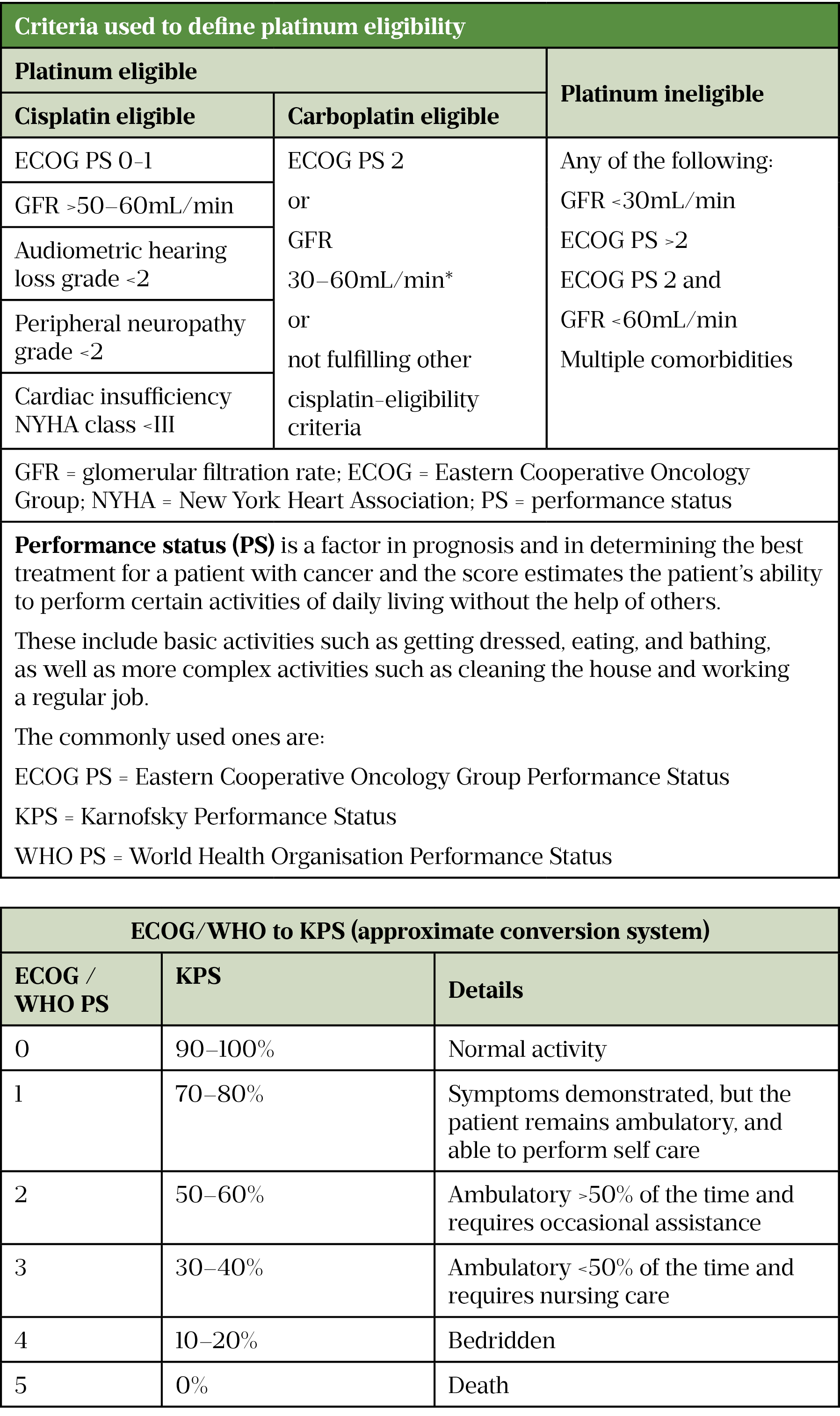

Cisplatin-based combinations are first-line treatment options for MIBC and metastatic UC; however, around 50% of patients are ineligible for cisplatin and struggle to tolerate chemotherapy. Table 2 outlines the eligibility and approach to treatment[46].

Table 2 footnote: The benefit of carboplatin-based therapy was demonstrated in patient’s glomerular filtration rate (GFR) between 30mL/min-60mL/min and/or a poor performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] ≥2) and this is the basis for this recommendation[13]. However, some centres use a lower GFR of >20mL/min as a guide to eligibility to receive carboplatin.

Neoadjuvant is the administration of chemotherapy before either surgery (cystectomy) or radiotherapy to shrink the cancer and lower the risk of recurrence[49]. NICE suggests offering “neoadjuvant chemotherapy using a cisplatin combination regimen before radical cystectomy or radical radiotherapy to people with newly diagnosed muscle‑invasive urothelial bladder cancer for whom cisplatin‑based chemotherapy is suitable”[35].

A 2005 meta-analysis, compared neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy plus cystectomy with cystectomy alone and showed 5% absolute increase in five-year overall survival (OS) and 9% absolute increase in five-year disease free survival[50].

However, there is a lack of clarity about the optimal regimen and several studies have confirmed that GC (gemcitabine/cisplatin) and MVAC (methotrexate/vinblastine/doxorubicin [formerly adriamycin]/cisplatin) regimens show similar pathologic complete response[51–53].

When muscle invasion was not present on initial biopsies before cystectomy, NICE suggests adjuvant (administered after surgery or radiotherapy) cisplatin combination chemotherapy after radical cystectomy with GC[35,49].

A detailed description of regimens used in UC and their common toxicities can be found in Table 3 [54–57].

Metastatic urothelial cancer

Metastatic UC (mUC) is when the disease has spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs, liver, lymph nodes in pelvis, abdomen or bones[22]. Initial management should be a cisplatin-based regimen, which demonstrates a 12–14 month OS[58].

Patients with mUC fall into three groups[13]:

- Fit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy;

- Fit for carboplatin-based chemotherapy (unfit for cisplatin); and

- Unfit for any platinum-based chemotherapy.

Figure 9 provides an outline of the management of metastatic UC and the place of each therapy.

Patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are fit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy

International guidelines recommend either GC or MVAC as first-line options for mUC patients fit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy[1,20,59].

This is because data from several randomised studies indicate that GC and MVAC have equivalent efficacy (similar overall response rate [ORR], time to progression and OS), but GC to have less toxicity (less weight loss, better performance status, less fatigue, deaths owing to toxicity, neutropenia, neutropenic sepsis and mucositis)[60–65].

A randomised trial has found that a dose-dense (dd) MVAC that delivers twice the doses of cisplatin and doxorubicin in half the time was associated with an improvement in complete responses and progression-free survival and with fewer dose delays and less toxicity than MVAC[62,63].

This is reflected in the guideline recommendations[2,13].

Carboplatin-containing chemotherapy is not considered to be equivalent to cisplatin-based combinations and should not be considered in patients fit for cisplatin[13].

Patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are ineligible for cisplatin-based regimens

An analysis of four randomised phase II trials of carboplatin versus cisplatin combination chemotherapy showed lower complete response rates and shorter OS for the carboplatin arms[64]. A multicentre, retrospective study (n=1,333) showed that eligible patients treated with cisplatin lived longer than those who were not and highlighted the importance of using cisplatin in eligible patients to improve survival[65]. It is important to therefore determine the basis for renal impairment before selecting a regimen and if there is a simple or reversible cause (e.g. urinary obstruction) that this is corrected to allow use of dd-MVAC or GC regimens.

The evidence for gemcitabine-carboplatin-based regimens (Gem-Carbo) comes from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial 30986, which included patients that had impaired renal function (GFR >30mL/min to <60mL/min) and/or a poor performance status (ECOG ≥2)[66]. At 4.5 years follow-up Gem-Carbo had similar ORR, median OS and median progression-free survival (PFS) compared to a regimen containing methotrexate/carboplatin/vinblastine (M-CAVI)[66].

Gem-Carbo caused less serious toxicities, such as neutropenia and febrile neutropenia[67].

Maintenance avelumab (an ICI) following initial platinum-based chemotherapy in mUC has been licensed following the JAVELIN-Bladder-100[67,68]. The use of maintenance avelumab in locally advanced unresectable or mUC (irrelevant of PD-L1 tumour expression) with either complete response or partial response or stable disease after four to six cycles of gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy provides an additional median OS of ten months[67].

Maintenance avelumab treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer that has not progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy is now recommended by international guidelines, with NICE recommending this indication provided it is stopped at five years of uninterrupted treatment or earlier if the disease progresses[1,20,59,69].

Patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are unfit for any platinum-based chemotherapy

Gemcitabine and paclitaxel have been studied as first-line treatment for mUC patients unfit for any platinum-based chemotherapy with reported ORR between 38% and 60% but have never been tested in randomised trials[70–72].

ICIs (atezolizumab and pembrolizumab) are licensed for monotherapy in mUC who are ineligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and whose tumour expresses PD-L1[73,74].

Two phase II, non-comparator studies, IMvigor210 and KEYNOTE-052 investigated atezolizumab and pembrolizumab respectively with the ORR between 23% and 29% and complete response 7% and 9%[75–77].

NICE recommends atezolizumab for untreated PD-L1-positive mUC when cisplatin is unsuitable, but in 2021 NICE issued a termination notice for pembrolizumab[78,79].

Three trials IMvigor 130 (atezolizumab), KEYNOTE-361 (pembrolizumab) and DANUBE (duravlumab) included an ICI alone arm[80–82]. No PFS or OS benefit was offered by single agent ICI compared with platinum-based chemotherapy; therefore, Gem-Carbo is the preferred treatment for patients ineligible for cisplatin but eligible for carboplatin.

Second-line management of metastatic urothelial cancer

It is reasonable to rechallenge in platinum-sensitive patients if progression occurred at least 6–12 months after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy[20]. NICE recommend atezolizumab, provided it is stopped at two years of uninterrupted treatment or earlier if the disease progresses[83]. NICE does not recommend pembrolizumab or nivolumab[84,85].

KEYNOTE-045 (pembrolizumab) and IMvigor211 (atezolizumab) are the only ICI phase III trials on second-line treatment[86–90].

KEYNOTE-045 demonstrated that pembrolizumab compared to chemotherapy (paclitaxel, docetaxel, or vinflunine) prolonged survival whereas IMvigor211 demonstrated that atezolizumab did not prolong survival[86,89].

While atezolizumab is both licensed and NICE approved in the UK, its US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval was withdrawn after the publication of IMvigor-211[73,83].

International guidelines recommend pembrolizumab over atezolizumab as the preferred standard of care immunotherapy in the second-line setting; however, this conflicts with the NICE approval of atezolizumab only[1,13,59].

There are several subsequent-lines of management for mUC that are yet to be approved in the UK. These include:

Enfortumab — an antibody drug conjugate (ADC) targeting Nectin-4 which is involved in tumour-cell growth and proliferation and adheres to cell adhesion molecule that is overexpressed in UC[13]. Enfortumab when compared with single-agent chemotherapy after prior platinum chemotherapy and ICI and showed an increase in median overall survival (13 months compared to 9 months)[91]. The most common treatment-related adverse events include alopecia (45%), peripheral neuropathy (34%), fatigue (31%, 7.4% grade ≥3), decreased appetite (31%), diarrhoea (24%), nausea (23%) and skin rash (16%, 7.4% grade ≥3).

Sacituzumab govitecan — another ADC that consists of a humanised monoclonal antibody targeting trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (Trop-2) conjugated to SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan[13]. The phase II TROPHY-U-01 study, administered sacituzumab govitecan to patients pre-treated with platinum-regimen and ICI found that 77% had a decrease in measurable disease with serious side effects: neutropenia (34%), febrile neutropenia (10%), fatigue (52%), alopecia (47%), nausea (60%), diarrhoea (10%), and decreased appetite (36%)[92].

Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) alteration was discovered during genomic profiling of UC (11). In 2019, the FDA approved erdafitinib, a pan-FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for mUC with susceptible FGFR2/3 alterations following platinum-containing chemotherapy including within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy[93]. This was based on a phase II study that showed ORR 40% (complete response 3% and 37% partial response) and ORR in those who received an immunotherapy 59%[94].

Enfortumab has recently been approved in Europe and the US while sacituzumab govitecan (97) and erdafitinib (57) has been approved in the United States[57,95–97].

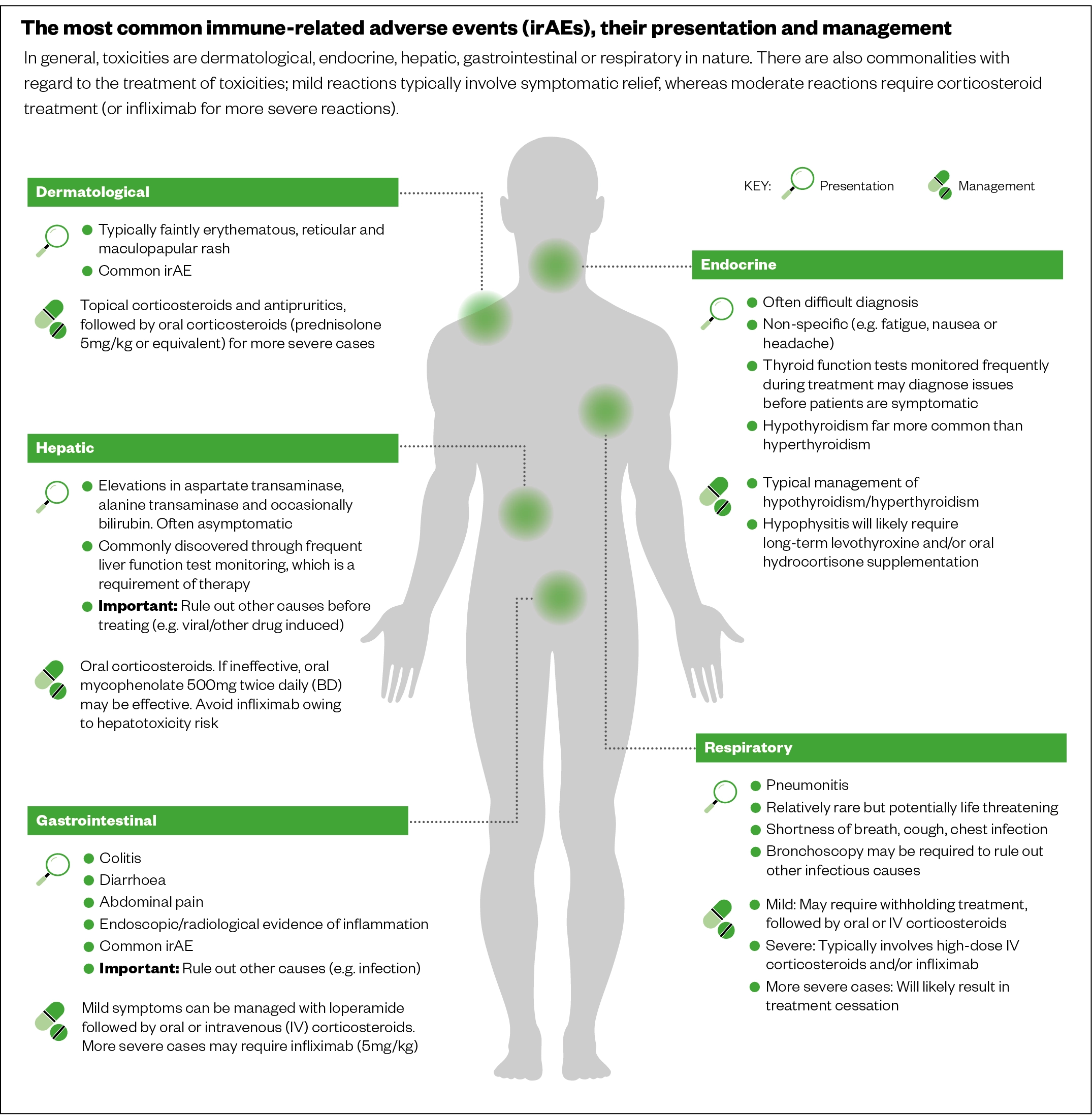

As all pharmacy teams may be a point of contact for cancer patients with potential life-threatening adverse events from treatments, it is therefore important to be able to recognise common adverse events including:

- Immune-mediated adverse events: can be severe or fatal, can occur in any organ system or tissue (see Figure 10)[55];

- Chemotherapy adverse events: neutropenia, neutropenic sepsis, nephrotoxicity, nausea and vomiting.

It is important that the patient urgently discusses potential adverse events and issues with the cancer team and should be referred to their oncology service for urgent advice. All services should run helplines that are easily accessed by patients.

A detailed description of regimens used in UC and their common toxicities can be found in Table 3.

Summary

An improved understanding of the genetics of UC has changed the way metastatic disease is treated. Intravesical BCG has remained the mainstay of therapy for intermediate and high-risk non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer, the therapeutic options for muscle-invasive and advanced disease are expanding to include immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors, targeted therapies, and antibody-drug conjugate.

Useful resources

- Cancer Research UK — Bladder Cancer;

- Macmillan Cancer Support — Bladder Cancer;

- Fight Bladder Cancer;

- Action Bladder Cancer UK;

- Cancer e-Learning for Community Pharmacy (module 1: Early diagnosis & prevention; module 2: What is Cancer?; module 3: Treatment of Cancer; module 4: Supporting your patients with cancer);

- Local hospital services — all NHS cancer teams have a patient helpline.

- 1Bladder cancer incidence. Cancer Research UK. 2022.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bladder-cancer#heading-Zero (accessed Apr 2022).

- 2Powles T, Bellmunt J, Comperat E, et al. Bladder cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2022;33:244–58. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.11.012

- 3Bladder cancer statistics. Cancer research UK. 2022.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bladder-cancer#heading-Zero (accessed Apr 2022).

- 4Burger M, Catto JWF, Dalbagni G, et al. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Urothelial Bladder Cancer. European Urology. 2013;63:234–41. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.033

- 5Freedman ND. Association Between Smoking and Risk of Bladder Cancer Among Men and Women. JAMA. 2011;306:737. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1142

- 6Welty CJ, Wright JL, Hotaling JM, et al. Persistence of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder risk among former smokers: Results from a contemporary, prospective cohort study. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2014;32:25.e21-25.e25. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.09.001

- 7Pharmacy guide to smoking cessation consultations. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2021. doi:10.1211/pj.2021.1.109105

- 8Lenis AT, Lec PM, Chamie K, et al. Bladder Cancer. JAMA. 2020;324:1980. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.17598

- 9Hayden A, Douglas J, Sommerlad M, et al. The Nrf2 transcription factor contributes to resistance to cisplatin in bladder cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2014;32:806–14. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.02.006

- 10Chalasani V, Chin JL, Izawa JI. Histologic variants of urothelial bladder cancer and nonurothelial histology in bladder cancer. CUAJ. 2013;3:193. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1195

- 11Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cell. 2017;171:540-556.e25. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.007

- 12Hedegaard J, Lamy P, Nordentoft I, et al. Comprehensive Transcriptional Analysis of Early-Stage Urothelial Carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:27–42. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2016.05.004

- 13Cathomas R, Lorch A, Bruins HM, et al. The 2021 Updated European Association of Urology Guidelines on Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. European Urology. 2022;81:95–103. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2021.09.026

- 14Groenendijk FH, de Jong J, Fransen van de Putte EE, et al. ERBB2 Mutations Characterize a Subgroup of Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancers with Excellent Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. European Urology. 2016;69:384–8. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.014

- 15Plimack ER, Dunbrack RL, Brennan TA, et al. Defects in DNA Repair Genes Predict Response to Neoadjuvant Cisplatin-based Chemotherapy in Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. European Urology. 2015;68:959–67. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.009

- 16Choi W, Porten S, Kim S, et al. Identification of Distinct Basal and Luminal Subtypes of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer with Different Sensitivities to Frontline Chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:152–65. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.009

- 17Kim J, Akbani R, Creighton CJ, et al. Invasive Bladder Cancer: Genomic Insights and Therapeutic Promise. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4514–24. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-14-1215

- 18Lotan Y, Choueiri TK. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging of bladder cancer. UpToDate. 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-diagnosis-and-staging-of-bladder-cancer?search=bladder%20cancer&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. (accessed Apr 2022).

- 19Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. NICE guideline [NG12]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 20Removing the bladder (cystectomy). Cancer Research UK. 2021.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/treatment/invasive/surgery/removing-bladder (accessed Apr 2022).

- 21Cystectomy (removing the bladder). Macmillan Cancer Support. 2021.https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/treatments-and-drugs/cystectomy-removing-the-bladder (accessed Apr 2022).

- 22About advanced bladder cancer. Cancer Research UK. 2022.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/advanced/about (accessed Apr 2022).

- 23Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th edition. 2nd ed. New York: : Wiley-Blackwell and UICC 2016. https://www.uicc.org/resources/tnm-classification-malignant-tumours-8th-edition (accessed Apr 2022).

- 24Shah A, Lemke E. Advances in the Management of Patients With Urothelial Carcinomas of the Bladder. J Adv Pract Oncol 2018;3:316–20.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6333559/

- 25Bladder Cancer > Types, stages and grades. Cancer Research UK. 2021.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/types-stages-grades/stages (accessed Apr 2022).

- 26Survival. Cancer Research UK. 2021.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/survival (accessed Apr 2022).

- 27Survival Rates for Bladder Cancer. American Cancer Society. 2021.https://www.cancer.org/cancer/bladder-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html (accessed Apr 2022).

- 28Transurethral resection of a bladder tumour (TURBT). Macmillan Cancer Support. 2021.https://www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/treatments-and-drugs/transurethral-resection-of-a-bladder-tumour-turbt (accessed Apr 2022).

- 29Trans urethral removal of bladder tumour (TURBT). Cancer Research UK. 2021.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/treatment/early/trans-urethral-removal-tumour (accessed Apr 2022).

- 30Herr H. Re: Marko Babjuk, Andreas Böhle, Maximilian Burger, et al. EAU Guidelines on Non–muscle-invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Update 2016. Eur Urol 2017;71:447–61. European Urology. 2017;71:e171–2. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.030

- 31Soukup V, Čapoun O, Cohen D, et al. Prognostic Performance and Reproducibility of the 1973 and 2004/2016 World Health Organization Grading Classification Systems in Non–muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A European Association of Urology Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel Systematic Review. European Urology. 2017;72:801–13. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2017.04.015

- 32Larsen ES, Joensen UN, Poulsen AM, et al. Bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy for bladder cancer: a review of immunological aspects, clinical effects and BCG infections. APMIS. 2020;128:92–103. doi:10.1111/apm.13011

- 33Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, et al. Guideline for the Management of Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (Stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 Update. Journal of Urology. 2007;178:2314–30. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.003

- 34Bosschieter J, Nieuwenhuijzen JA, van Ginkel T, et al. Value of an Immediate Intravesical Instillation of Mitomycin C in Patients with Non–muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Prospective Multicentre Randomised Study in 2243 patients. European Urology. 2018;73:226–32. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2017.06.038

- 35Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG2]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng2/chapter/1-recommendations (accessed Apr 2022).

- 36Friedrich MG, Pichlmeier U, Schwaibold H, et al. Long-Term Intravesical Adjuvant Chemotherapy Further Reduces Recurrence Rate Compared with Short-Term Intravesical Chemotherapy and Short-Term Therapy with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) in Patients with Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Carcinoma. European Urology. 2007;52:1123–30. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.063

- 37SYLVESTER RJ, van der MEIJDEN APM, WITJES JA, et al. BACILLUS CALMETTE-GUERIN VERSUS CHEMOTHERAPY FOR THE INTRAVESICAL TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH CARCINOMA IN SITU OF THE BLADDER: A META-ANALYSIS OF THE PUBLISHED RESULTS OF RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIALS. Journal of Urology. 2005;174:86–91. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000162059.64886.1c

- 38Cumberbatch MGK, Foerster B, Catto JWF, et al. Repeat Transurethral Resection in Non–muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. European Urology. 2018;73:925–33. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2018.02.014

- 39Oddens J, Brausi M, Sylvester R, et al. Final Results of an EORTC-GU Cancers Group Randomized Study of Maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guérin in Intermediate- and High-risk Ta, T1 Papillary Carcinoma of the Urinary Bladder: One-third Dose Versus Full Dose and 1 Year Versus 3 Years of Maintenance. European Urology. 2013;63:462–72. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.039

- 40Morales A, Nickel J. Immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer. A developmental and clinical overview. Urol Clin North Am 1992;19:549–56.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1378982

- 41Green DB, Kawashima A, Menias CO, et al. Complications of Intravesical BCG Immunotherapy for Bladder Cancer. RadioGraphics. 2019;39:80–94. doi:10.1148/rg.2019180014

- 42Zlotta AR, Fleshner NE, Jewett MA. The management of BCG failure in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an update. CUAJ. 2013;3:199. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1196

- 43Gual F, Palou J, Rodríguez O, et al. Failure of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Definition and treatment options. Arch Esp Urol 2016;69:423–33.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27617552

- 44KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) injection, for intravenous use. US Food and Drug Administration. 2021.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/125514s120lbl.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 45Balar AV, Kamat AM, Kulkarni GS, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for the treatment of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer unresponsive to BCG (KEYNOTE-057): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2021;22:919–30. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00147-9

- 46Galsky MD, Hahn NM, Rosenberg J, et al. Treatment of Patients With Metastatic Urothelial Cancer “Unfit” for Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy. JCO. 2011;29:2432–8. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.34.8433

- 47Guidance on the use of temozolomide for the treatment of recurrent malignant glioma (brain cancer). Technology appraisal guidance [TA23]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta23/chapter/Appendix-D-Karnofsky-Performance-Score (accessed Apr 2022).

- 48West H (Jack), Jin JO. Performance Status in Patients With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:998. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3113

- 49Having chemotherapy for bladder cancer. Cancer Research UK. 2022.https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/treatment/invasive/chemotherapy/treatment (accessed Apr 2022).

- 50Vale CL. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Invasive Bladder Cancer: Update of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. European Urology. 2005;48:202–6. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.04.006

- 51Galsky MD, Pal SK, Chowdhury S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:2586–93. doi:10.1002/cncr.29387

- 52Pfister C, Gravis G, Fléchon A, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Dose-dense Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicin, and Cisplatin, or Gemcitabine and Cisplatin as Perioperative Chemotherapy for Patients with Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Analysis of the GETUG/AFU V05 VESPER Trial Secondary Endpoints: Chemotherapy Toxicity and Pathological Responses. European Urology. 2021;79:214–21. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2020.08.024

- 53Flaig TW, Tangen CM, Daneshmand S, et al. A Randomized Phase II Study of Coexpression Extrapolation (COXEN) with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Bladder Cancer (SWOG S1314; NCT02177695). Clinical Cancer Research. 2021;27:2435–41. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-2409

- 54Bellmunt J, Lerner SP, Shah S. Treatment of metastatic urothelial cancer of the bladder and urinary tract. UpToDate. 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-metastatic-urothelial-cancer-of-the-bladder-and-urinary-tract?search=bladder%20cancer%20treatment&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=2 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 55Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer: pharmacology and toxicities. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018. doi:10.1211/pj.2018.20204831

- 56Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. JCO. 2021;39:4073–126. doi:10.1200/jco.21.01440

- 57BALVERSA® (erdafitinib) tablets, for oral use. US Food and Drug Administration. 2021.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/212018s001lbl.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 58Bellmunt J, Petrylak DP. New Therapeutic Challenges in Advanced Bladder Cancer. Seminars in Oncology. 2012;39:598–607. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.08.007

- 59NCCN National Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Bladder Cancer. NCCN. 2021.https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).

- 60Lehmann J, Retz M, Steiner G, et al. Gemcitabin/Cisplatin vs. MVAC. Der Urologe A. 2003;42:1074–86. doi:10.1007/s00120-003-0317-4

- 61von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-Term Survival Results of a Randomized Trial Comparing Gemcitabine Plus Cisplatin, With Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicin, Plus Cisplatin in Patients With Bladder Cancer. JCO. 2005;23:4602–8. doi:10.1200/jco.2005.07.757

- 62Sternberg CN, de Mulder P, Schornagel JH, et al. Seven year update of an EORTC phase III trial of high-dose intensity M-VAC chemotherapy and G-CSF versus classic M-VAC in advanced urothelial tract tumours. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42:50–4. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.032

- 63Sternberg CN, de Mulder PHM, Schornagel JH, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of High–Dose-Intensity Methotrexate, Vinblastine, Doxorubicin, and Cisplatin (MVAC) Chemotherapy and Recombinant Human Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor Versus Classic MVAC in Advanced Urothelial Tract Tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Protocol No. 30924. JCO. 2001;19:2638–46. doi:10.1200/jco.2001.19.10.2638

- 64Galsky MD, Chen GJ, Oh WK, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cisplatin-based and carboplatin-based chemotherapy for treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23:406–10. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr156

- 65Bamias A, Tzannis K, Harshman LC, et al. Impact of contemporary patterns of chemotherapy utilization on survival in patients with advanced cancer of the urinary tract: a Retrospective International Study of Invasive/Advanced Cancer of the Urothelium (RISC). Annals of Oncology. 2018;29:361–9. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx692

- 66De Santis M, Bellmunt J, Mead G, et al. Randomized Phase II/III Trial Assessing Gemcitabine/Carboplatin and Methotrexate/Carboplatin/Vinblastine in Patients With Advanced Urothelial Cancer Who Are Unfit for Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy: EORTC Study 30986. JCO. 2012;30:191–9. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.37.3571

- 67Powles T, Park SH, Voog E, et al. Avelumab Maintenance Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1218–30. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2002788

- 68Bavencio 20 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8453 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 69Avelumab for maintenance treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer after platinum-based chemotherapy [ID3735]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ta10624 (accessed Apr 2022).

- 70Sternberg CN, Calabr� F, Pizzocaro G, et al. Chemotherapy with an every-2-week regimen of gemcitabine and paclitaxel in patients with transitional cell carcinoma who have received prior cisplatin-based therapy. Cancer. 2001;92:2993–8. doi:71Meluch AA, Greco FA, Burris HA III, et al. Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine Chemotherapy for Advanced Transitional-Cell Carcinoma of the Urothelial Tract: A Phase II Trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. JCO. 2001;19:3018–24. doi:10.1200/jco.2001.19.12.301872Calabrò F, Lorusso V, Rosati G, et al. Gemcitabine and paclitaxel every 2 weeks in patients with previously untreated urothelial carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115:2652–9. doi:10.1002/cncr.2431373Tecentriq 1,200 mg concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8442/smpc (accessed Apr 2022).74KEYTRUDA 25 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion. Electronic Medicines Compendium. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2498 (accessed Apr 2022).75Balar AV, Galsky MD, Rosenberg JE, et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. The Lancet. 2017;389:67–76. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32455-276Balar AV, Castellano D, O’Donnell PH, et al. First-line pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer (KEYNOTE-052): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2017;18:1483–92. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30616-277Vuky J, Balar AV, Castellano D, et al. Long-Term Outcomes in KEYNOTE-052: Phase II Study Investigating First-Line Pembrolizumab in Cisplatin-Ineligible Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Cancer. JCO. 2020;38:2658–66. doi:10.1200/jco.19.0121378Atezolizumab for untreated PD-L1-positive advanced urothelial cancer when cisplatin is unsuitable. Technology appraisal guidance [TA739]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta739 (accessed Apr 2022).79Pembrolizumab for untreated PD-L1-positive, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer when cisplatin is unsuitable (terminated appraisal). Technology appraisal [TA674]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta674 (accessed Apr 2022).80Galsky MD, Arija JÁA, Bamias A, et al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2020;395:1547–57. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30230-081Powles T, Csőszi T, Özgüroğlu M, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma (KEYNOTE-361): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2021;22:931–45. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00152-282Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Castellano D, et al. Durvalumab alone and durvalumab plus tremelimumab versus chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (DANUBE): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21:1574–88. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30541-683Atezolizumab for treating locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum-containing chemotherapy. Technology appraisal guidance [TA525]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta525 (accessed Apr 2022).84Pembrolizumab for treating locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum-containing chemotherapy. Technology appraisal guidance [TA692]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta692 (accessed Apr 2022).85Nivolumab for treating locally advanced unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer after platinum-containing chemotherapy. Technology appraisal guidance [TA530]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta530 (accessed Apr 2022).86Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. Pembrolizumab as Second-Line Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1015–26. doi:10.1056/nejmoa161368387Fradet Y, Bellmunt J, Vaughn DJ, et al. Randomized phase III KEYNOTE-045 trial of pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel, docetaxel, or vinflunine in recurrent advanced urothelial cancer: results of >2 years of follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2019;30:970–6. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz12788Vaughn DJ, Bellmunt J, Fradet Y, et al. Health-Related Quality-of-Life Analysis From KEYNOTE-045: A Phase III Study of Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Previously Treated Advanced Urothelial Cancer. JCO. 2018;36:1579–87. doi:10.1200/jco.2017.76.956289Powles T, Durán I, van der Heijden MS, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2018;391:748–57. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33297-x90van der Heijden MS, Loriot Y, Durán I, et al. Atezolizumab Versus Chemotherapy in Patients with Platinum-treated Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: A Long-term Overall Survival and Safety Update from the Phase 3 IMvigor211 Clinical Trial. European Urology. 2021;80:7–11. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2021.03.02491Powles T, Rosenberg JE, Sonpavde GP, et al. Enfortumab Vedotin in Previously Treated Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1125–35. doi:10.1056/nejmoa203580792Tagawa ST, Balar AV, Petrylak DP, et al. TROPHY-U-01: A Phase II Open-Label Study of Sacituzumab Govitecan in Patients With Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Progressing After Platinum-Based Chemotherapy and Checkpoint Inhibitors. JCO. 2021;39:2474–85. doi:10.1200/jco.20.0348993BALVERSA® (erdafitinib) tablets, for oral use. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/212018s001lbl.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).94Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, et al. Erdafitinib in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:338–48. doi:10.1056/nejmoa181732395Padcev: Pending EC decision. European Medicines Agency . 2021.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/summaries-opinion/padcev (accessed Apr 2022).96PADCEVTM (enfortumab vedotin-ejfv) for injection, for intravenous use. US Food and Drug Administration. 2021.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761137s000lbl.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).97TRODELVY® (sacituzumab govitecan-hziy) for injection, for intravenous use. US Food and Drug Administration. 2021.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761115s009lbl.pdf (accessed Apr 2022).