Mclean/Shutterstock.com

Genomic medicine is no longer a thing of the future — it is here.

In several countries, including the UK, pharmacists are already carrying out genetic testing as part of their day-to-day practice, interpreting the results and often adjusting patients’ medicines as a result.

As part of the 100,000 Genomes Project, which launched in 2013, the genomes of 85,000 NHS patients affected by rare disease or cancer have been sequenced, and this has already had an impact on the treatment of patients with cancer and rare diseases, such as Huntingdon’s disease or Fragile X syndrome.

For instance, all four UK nations now routinely test for the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) gene on the NHS, as the presence of certain variants increase a patient’s risk of severe or fatal toxicity to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapies.

However, tests such as these are only the beginning. Increasingly, genetic information is being used around the world, in countries including the United States, the Netherlands and Canada, to personalise people’s medical treatment, with the effectiveness and safety of common drugs — such as opioids and antidepressants — all potentially affected by genetic differences between individuals.

Genomics won’t just transform medicine for pharmacy; it will transform medicine for the whole healthcare system

Ravi Sharma, director for England at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

In 2018, the NHS Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) launched in England and, in the same year, the Genomics Partnership Wales was launched to embed genomic medicine into the Welsh health service. Then, in March 2022, it was revealed that the NHS in Scotland was tendering a £66m pharmacogenomics and pharmaceutical clinical decision support service, developed to identify patients who are at the greatest risk of harm.

“At the moment, it’s very niche,” says Ravi Sharma, director for England at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS).

“You will hear of DPYD testing being done quite often, as a good example of wide-scale pharmacogenomics implementation, but when you look at the strategic priorities for [the] NHS, there will be huge opportunities to do pharmacogenomics testing and analysis.

“Genomics won’t just transform medicine for pharmacy; it will transform medicine for the whole healthcare system.”

Lack of confidence

Pharmacists’ expertise is going to be crucial in this transformation.

“There’s plenty of global evidence that shows successful implementation models need pharmacy leadership,” Sharma adds.

“If you look at the Netherlands, United States, Scandinavia, and you look at other parts of Europe — it’s quite critical that a pharmacist in some form is part of their clinical pathway and process. The NHS in England and Scotland and Wales realise that as well and they are putting infrastructures in place that shows pharmacy leadership is critically important.”

Each GMS Alliance (GMSA), the regional branches of the GMS, now has a chief pharmacist and a lead or consultant pharmacist with a focus on research and delivery of the GMSA’s priorities. In 2021, the Scottish Pharmacy Clinical Leadership Fellowship scheme appointed Jill Swan, principal pharmacist in clinical services at NHS Ayrshire and Arran, to lead on pharmacogenomics, following from Katherine Davidson, who was appointed to the role in 2020.

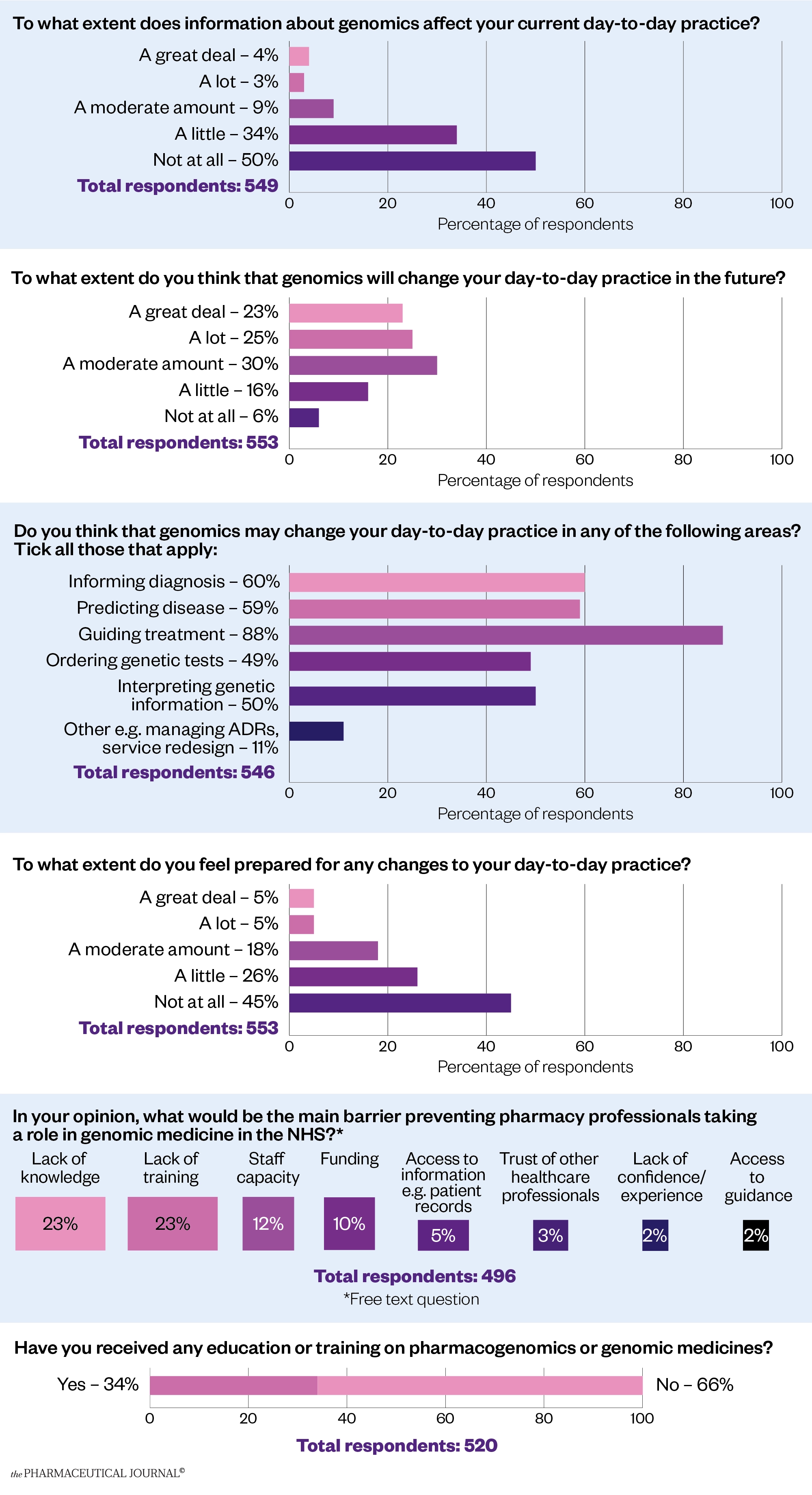

The wider profession is realising that it must get to grips with this new way of working. A survey of more than 600 UK pharmacy professionals from all sectors carried out by The Pharmaceutical Journal in January and February 2022 revealed that the vast majority (94%) of respondents say they expect genomics to change their day-to-day practice in the future, even if just to a small extent (see Figure).

The survey also showed that most respondents (88%) expected to use pharmacogenomics to guide the treatment of patients in future, and more than half thought it would be used to predict disease (59%) and inform diagnosis (60%). Half of the respondents expected to find themselves ordering genetic tests (49%) and interpreting genetic information (50%).

However, the results also show that confidence in the profession is low, with only 10% saying they were very confident that they were prepared for the changes to daily practice that they anticipate coming.

When asked what barriers they perceived to pharmacy professionals taking a role in genomic medicine in the NHS, by far the most cited one was a lack of knowledge and training, but staff capacity and funding were also mentioned frequently.

Two thirds of respondents (66%) have never received any training on pharmacogenomics or genomic medicine, with many saying this was covered in their MPharm course or that they had undertaken some self-directed study.

This is an important area for which there is little training or understanding among pharmacists, particularly those who qualified more than ten years ago

respondent to a survey carried out by the pharmaceutical journal

As one respondent said: “This is an important area for which there is little training or understanding among pharmacists, particularly those who qualified more than ten years ago.”

Another put it more succinctly: “Big gap in my knowledge. I want to be an early adopter and not a laggard.”

Training opportunities

This climate is changing. For new pharmacists, the General Pharmaceutical Council’s standards for the initial education and training of pharmacists, published in January 2021, says that pharmacists should have an “understanding of genomics and how it is applied to drug development as well as patient care” at the point of registration.

For those already on the pharmacy workforce, there are limited learning opportunities. There are several university postgraduate courses that can give a theoretical grounding in genomic medicine across the UK, but a full master’s degree can take up to two years to complete part time and can cost up to £12,000.

There are bursaries available for a set number of places on these courses and Health Education England’s Genomics Education Programme (GEP) offers a master’s in genomic medicine. NHS professionals can apply for course funding and modules, including ‘pharmaceogenomics and stratified healthcare’, can be taken individually as part of continuing professional development.

For a less intensive introduction to genomics, the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE) offers a £10 online course for pharmacists providing an introduction to genomics in pharmacy, which takes two hours of learning time. For a full list of the funding and various options available across the UK, see ‘Box’.

However, experts say that formal training is not necessarily the kind of education that pharmacists will require to take an active role in implementing pharmacogenomics into the NHS.

David Wright, professor of health services research at the University of Leicester’s School of Allied Health Professions, says that even though pharmacogenomics and genetics are taught on the undergraduate pharmacy course in the Netherlands, experience in the field is what matters.

“Even they, after all that [undergraduate study], say they’re not competent, really. That’s because that knowledge is hard science, but it doesn’t tell them what to do when they’re faced with a patient,” he explains.

“So that’s where the training needs to be. You’ve got to trust the science. You haven’t got to spend years learning about and understanding DNA, and everything associated with drug response. What you’ve got to understand is the quality of information you’ve been given and how to use it. And again, that comes with experience”.

Sophie Harding, pharmacogenomics lead at the RPS, agrees. “There is insufficient training available for pharmacy staff across all healthcare sectors. Many pharmacy staff do not need to be an expert in genomics but they do need to have a suitable level of knowledge and understanding in order to fulfil their day-to-day pharmacy role, which will be impacted by pharmacogenomics.

“A collaborative approach is needed between all organisations across the UK nations, to provide appropriate education resources focused at pharmacy staff related to their individual learning needs.”

A report published by the Royal College of Physicians and the British Pharmacological Society in March 2022 — ‘Personalised prescribing: using pharmacogenomics to improve patient outcomes’ — says the implementation of pharmacogenomics needs to be “accompanied by a comprehensive education and training package aimed at all sectors of healthcare to improve the skills of the workforce and embed pharmacogenomics into curricula for training the future workforce”.

It recommends “a layered approach to learning so that healthcare professionals can access ‘just-in-time’ information, short courses or formal qualifications, depending on their professional requirements and personal interests”.

Decision support

But the level of training required by pharmacists will depend on the access to information and support they are given when implementing pharmacogenomic testing.

Information sharing will be a particular problem in community pharmacy. As one respondent to The Pharmaceutical Journal’s survey said: “In community, it is always difficult to advise the patients on their own specific variations, as we never get to see blood test or investigation results. We might be able to look at summary care records, but are working blindly treating and advising.”

As well as access to patient records, experts say that it will be crucial to provide pharmacists with suitable clinical decision support software that means they can be confident they are giving the right advice.

I don’t think the training needs to be over-complicated to make it the new baseline for everybody

Tracey Thornley, an honorary professor in pharmacy practice at the University of Nottingham

Tracey Thornley, an honorary professor in pharmacy practice at the University of Nottingham, has published research on pharmacogenomics in Dutch community pharmacies. She says the most important area to support pharmacogenetics implementation in practice will be “having the right IT algorithms and infrastructure in place that helps to guide recommendations arising from pharmacogenomics testing”.

“I don’t think the training needs to be over-complicated to make it the new baseline for everybody,” she adds. “I don’t want to oversimplify it, but I also think we shouldn’t overcomplicate it.

“To me this is just about us tailoring the medicines. It’s making it so that it’s more suitable for the person first time: the right dose, and the right medicine. Pharmacogenomics in its simplest form is just an extension of medicines adherence.

“Pharmacists are already experts in medicines use and, if all the enablers are in place, it will become the new norm going forward.”

Wright agrees: “Although the science underpinning [pharmacogenomics] is very high level, the information they need to know is very similar to what you need for knowing how to respond to a drug interaction. Because, effectively, what you’ve identified is a body–drug interaction, rather than a drug–drug interaction.

“It’s just knowing how to respond to that information, and generally when you get the report it says: reduce the dose, or stop the medicine, or change it. The report you get back generally gives you the advice you need to then make a decision, so you don’t really need to understand in any great depth.”

Wright says he would like to see more case studies for training purposes. “And, after a number of those, you will probably be in a position where you can say ‘this is how I would respond’. This is an opportunity that pharmacy needs to seize and they have the skills to do it.”

Box: Genomics training across the UK

England

Health Education England (HEE) provides a module on ‘Pharmacogenomics and stratified healthcare’, which can be taken on its own or as part of a longer course. HEE says the module is funded for students in England working in permanent, full-time posts in the NHS to undertake modules as individual CPD, as part of a PGCert, PGDip or a full master’s degree.

HEE has hinted that this offering may expand in future. A spokesperson told The Pharmaceutical Journal that it is currently working on developing a range of educational materials for pharmacy staff around genomics and pharmacogenomics as part of its genomics education programme.

The spokesperson added that the main element of this pharmacy strategy is a UK-wide survey, ‘Genomics in your practice’, which was open to everyone working in a pharmacy role in the UK, including pharmacy technicians, assistants/support staff and pharmacists, until 15 April 2022. HEE will use feedback from this to identify main areas where genomic education and training is needed.

Scotland

According to a spokesperson for NHS Scotland, the universities of Glasgow, Aberdeen and Strathclyde, in collaboration with the universities of Dundee and Edinburgh, offer a MSc in ‘Precision medicine and pharmacological intervention’. For eligible applicants, including Scottish citizens, as well as people who have been ordinarily resident in Scotland for the three years before starting the course, the fees for this course are covered by the Scottish Funding Council.

Pharmacists in Scotland can also access the online resources provided by the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education and HEE (for a fee), plus webinars from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), if they are members.

The RPS also currently offers members a pre-recorded webinar on pharmacogenomics: ‘Taking it personally: pharmacogenomics and the future of medications safety’.

The NHS Scotland spokesperson added that it does not currently offer specific funding for training in pharmacogenomics, but said NHS Scotland was “currently surveying staff to get a better understanding of their educational needs” as part of the national survey accessible through HEE.

Wales

In Wales, Health Education and Improvement Wales is funding 15 places on Swansea University’s ‘Genomic medicine’ MSc.