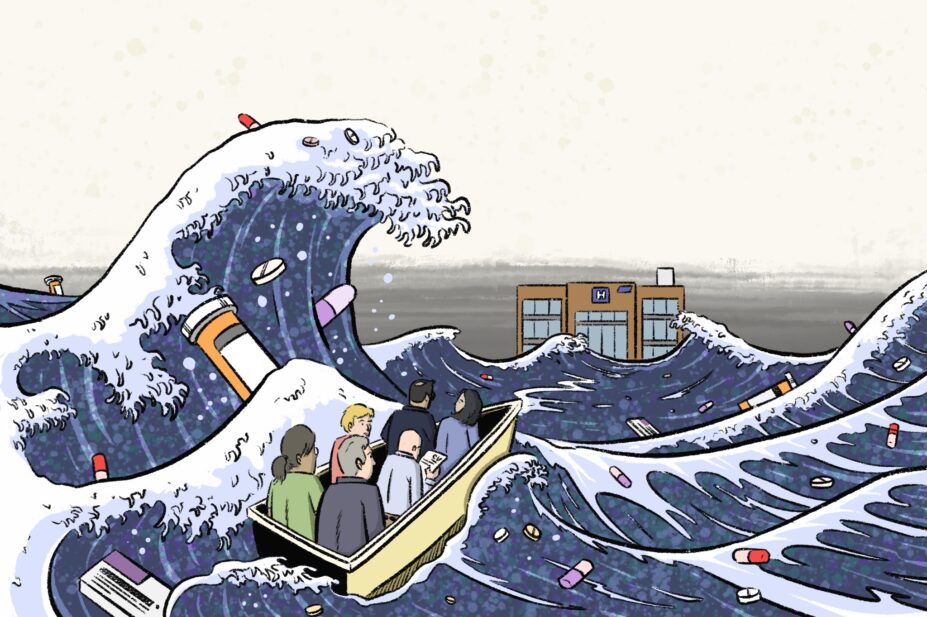

Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

A ‘perfect storm’ of recruitment and funding challenges is brewing within hospital pharmacy, leaving the workforce stretched thin.

“There’s a flux of staffing between the different sectors that people are working in. It’s stabilising, but that is definitely affecting hospital pharmacy teams,” says Nathan Burley, president of the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists.

“There is also a significant volume of work associated with hosting students, coupled with increased clinical service demand and financial pressures. It’s an absolute perfect storm,” he adds.

Declining rates of medicines reconciliations — currently an important metric for clinical pharmacy services — are a symptom of these workforce challenges.

According to Ruth Bednall, assistant director of quality improvement at University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust, medicines reconciliation is the activity that consumes the most time in the clinical service.

Medicines reconciliation is the process of identifying an accurate list of a person’s current medicines and comparing that with the list in use in the hospital, recognising any discrepancies and documenting any changes[1].

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) advises that each patient should have their medicines reconciled within 24 hours of hospital admission[1]. However, analysis of figures obtained by The Pharmaceutical Journal, following a Freedom of Information (FOI) request sent to all NHS trusts, shows that this is not a routine occurrence.

Among the 48 NHS acute trusts that responded with useable data, on average, medicines reconciliations were carried out for 58% of patients within 24 hours of admission in 2022/2023 (see Figure). The data also reveal a gradual decline in the average rate, from 66% of patients in 2020/2021.

During the past five years, no trust recorded having completed a medicines reconciliation for 100% of patients admitted to hospital within 24 hours.

Increased demand

The decline in rates of medicines reconciliation is partly owing to an increase in demand for clinical pharmacy services, forcing pharmacy teams to prioritise discharging patients ahead of other clinical services as trusts aim to turn over as many patients as possible.

In England, data published by NHS Digital show that there were 16.4 million NHS hospital admissions recorded in 2022/2023, a 2.6% increase from the previous year[2].

“One of the biggest challenges is the operational pressures within the organisation,” says Elisabeth Street, clinical director of pharmacy at Calderdale and Huddersfield Trust.

“We absolutely get what a good medicine service should look like, you should see patients at the front door, get the medicines reconciliation done within 24 hours, and follow them through to hopefully review their [medicines] every day they’re in, and at the point of discharge.

“But because of the operational pressures to free up that bed capacity, there’s so much pressure on [to take out medicines dispensed for patients on discharge], which is probably the biggest driver of not doing medicines reconciliations,” she says, adding that this can be frustrating for pharmacists.

Pharmacists are having to handle a more complex workload with lower resources at the same rate

Nathan Burley, president of the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists.

Burley explains that the ageing population of the UK plays a large role in the increased service needs. According to the latest census figures in 2021, the number of people aged 65 years and over has increased from 9.2 million in 2011 to more than 11.0 million in 2021, increasing from 16.4% to 18.6% of the population[3].

“As the population ages, people take more medicines — it’s as simple as that,” says Burley.

“They come to hospital with those medicines, so it takes longer to tease apart the priorities and review these patients, managing the dose, interactions, withholding medicines etc.

“Pharmacists are having to handle a more complex workload with lower resources at the same rate,” he adds.

Recruitment difficulties

Increasing difficulties in recruiting pharmacists is another factor influencing the ability to provide timely medicines reconciliations. With primary care offering a higher income, more desirable working hours and the option of remote working, many hospital pharmacy departments have been struggling to fill vacancies.

Data published by NHS Digital in February 2024 show that there were 24.5% more pharmacists in general practice and primary care networks at the end of 2023, compared with the end of 2022[4].

Meanwhile, data from the NHS Benchmarking Network‘s Pharmacy and Medicines Optimisation project in 2023/2024 revealed a median vacancy rate within NHS trusts of 13.0% for the total pharmacy workforce and 15.2% for pharmacists[5].

However, in many trusts these figures are much higher, with several acute trusts reporting pharmacy staff vacancy rates of around 30%, according to data received by The Pharmaceutical Journal following its FOI request. Bednall says these numbers are quite common within the NHS.

“Recruitment has been increasingly difficult. I know from conversations with colleagues that there are a lot of hospital pharmacies that are running on probably two-thirds of their staffing establishment,” says Bednall.

Our junior pharmacists coming in want greater flexibility

Ruth Bednall, assistant director of quality improvement at University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust

She puts this down to a change in how people want to balance their work and home lives since the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In hospital pharmacy, we’re quite fixed, Monday to Friday, nine to five, the weekends, and if you’re a junior, you’re probably going to be on call as well.

“It’s really quite rigid because there’s a service to be delivered and I think, especially our junior pharmacists coming in, want greater flexibility,” she says.

Raliat Onatade, chief pharmacist at the North East London Integrated Care System, adds that recruitment gets progressively harder with specialist roles. She explains that, as pharmacists gain more seniority, there are more employment opportunities available, which makes hospital vacancies harder to fill owing to increased competition for these pharmacists.

To combat challenges with recruitment, Evelyn Allen, chief pharmacist at Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust, has found success in filling vacancies by employing pharmacists from the European Economic Area (EEA) via a scheme run by the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC)[6].

“We’ve got pharmacists that have qualified from other European countries, such as Bulgaria,” says Allen. “They come in quite junior, at band six level, very similar to how we would take on a community pharmacist. We support them along the way, and hopefully by investing in them, they can stay,” she adds.

Currently, the EEA scheme is one of two main routes to registration for non-GB-trained pharmacists, with those from outside the EEA having to study the Overseas Pharmacists’ Assessment Programme (OSPAP) at university for one year and then complete a year of foundation training before they can take the GPhC registration assessment.

This may soon expand, with the GPhC announcing in February 2024 that it is considering a new framework that would allow pharmacists from countries where initial education and training is similar to that in Great Britain — such as New Zealand, Ireland and Australia — to spend as little as three months working under supervision in a GB pharmacy, with a practical assessment, before registering to practise[7].

Allen says an alternative solution to drive hospital pharmacy recruitment is the introduction of multisector roles. She believes providing opportunities where pharmacists can divide their time between hospital and primary care will attract more foundation pharmacists.

“These roles are difficult to arrange, with funding, managing rotations, and how we can support it, but we’re working on that,” says Allen.

Lack of funding

Difficulties in obtaining more funds for clinical pharmacy staff are another potential contributor to the decline in medicines reconciliations. Chief pharmacists at each NHS trust request funding for their departments by putting forward a business case and quality improvement plan to obtain the money required to run the department effectively. In some cases, additional funding may be provided by NHS England to support the pharmacy department in purchasing high-cost drugs.

It’s very hard to go to somebody and say, ‘I need this’ when there isn’t a national measure behind it

Mohamed Rahman, chief pharmacist at Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Unlike other healthcare professions, such as doctors and nurses, pharmacy does not have a mandated approach to staffing levels (e.g. number of pharmacists per occupied beds)[8–10]. This presents a unique challenge for chief pharmacists, who need to justify capacity requirements to gain more funding.

“It’s very hard to go to somebody and say, ‘I need this’ when there isn’t a national measure behind it,” says Mohamed Rahman, chief pharmacist at Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

“It’s frustrating when you are writing a business case because there is no magic calculator you can pick up that says this is how you work out how much resource you need,” he says.

In response, a team of pharmacists led by Bednall in Stoke-on-Trent, created the clinical pharmacy workforce calculator (CPWC) in March 2022[11]. The tool uses similar methodology to the World Health Organization’s workload indicators of staffing need method.

The calculator factors in the average time taken for each clinical activity, the number of beds, patients and length of stay to guide users on the number of pharmacy staff required and the estimated costs for a general ward.

Many chief pharmacists are aware of the tool but, Bednall says, without support from an authoritative body, such as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), national use is not feasible.

However, Claire Anderson, president of the RPS, says that an “outcome-based approach (rather than endorsing specific staffing levels, e.g. numbers of whole-time equivalents and/or time spent delivering care in a specific setting) is focused on person-centred care and enables our members to use their professional judgment in the context of local service delivery”.

She adds that setting safe pharmacy staffing levels is the responsibility of those managing pharmacy services at a local level or specialties working closely with patients.

Anderson refers to the RPS professional standards for hospital pharmacy services, which outline that staffing levels are to be determined by chief pharmacists to ensure delivery of safe daily services[12].

Rahman agrees that having a national standard for pharmacists per bed or ward is difficult, but adds that, while there is no ‘one size fits all’ clinical pharmacy measure, the CPWC is a good tool, and building on this with a clearly defined scope and role of a pharmacist within each specialty could be a promising step towards better allocation of funding.

A positive example of this is in acute services, where specialised organisations, such as the Royal College of Emergency Medicine and the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, have collaborated with the UK Clinical Pharmacy Association to produce standardised requirements for the clinical pharmacy service in their field[13,14].

Rahman encourages other specialty organisations to endorse this method and make recommendations on their pharmacy needs, which may provide additional funding for pharmacists from the specialty, rather than the pharmacy department.

Metrics evolve with the profession

From 2026, all newly qualified pharmacists will be active prescribers, allowing them to complete all components of the medicines reconciliation process.

“Medicines reconciliation generally has three stages. One is taking the drug history, then identifying any discrepancies between what [the patient] should be on and what they are then prescribed, and the third is correcting those discrepancies,” explains Onatade.

“A lot of the time is spent on correcting discrepancies via a prescriber, so independent prescribing should help improve the medicines reconciliation numbers,” she says.

Bednall adds that the increasing scope of pharmacy technicians will free up pharmacists’ time, enabling them to spend more time on clinical activities. Having a dedicated pharmacist to attend ward rounds, clinically review complex patients and sign off medicines reconciliation will add the most value to the clinical pharmacy service, she says.

While medicines reconciliation is likely to remain a vital component of clinical pharmacy, Burley says there needs to be a shift in focus towards where pharmacists have the most benefit.

“We need to evaluate where the impact is felt most by pharmacy staff, and just because we’ve done a metric in a certain way before, doesn’t mean we have to keep doing it in that way,” he says.

“For example, focusing on keeping people out of hospital and investing in outpatient roles.

“There is no denying that if you keep people healthier at home longer, they won’t have to come to us,” he adds.

Burley also suggests putting a greater onus on patients to take part in their own medicines reconciliation process, such as self-verification of medicines, as a viable way forward.

While NICE says that medicines reconciliation enables “early action to be taken when discrepancies between lists of medicines are identified”, Bednall questions its evidence base, which was generated in the late 1990s[15]. More recent studies suggest its impact may not be as influential as initially thought[16,17].

Bednall believes that, with increased technology and digitalisation of health records across all sectors, the process of medicines reconciliation may disappear.

“Medicines reconciliation is really an area we as a profession should be challenging,” she says.

- This article was amended on 15 April 2024 to correct Elisabeth Street’s job title

- 1National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. NICE guideline [NG5]. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 2NHS England. Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2022-23. NHS Digital. 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-admitted-patient-care-activity/2022-23 (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 3Office for National Statistics. Profile of the older population living in England and Wales in 2021 and changes since 2011. Census 2021. 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/profileoftheolderpopulationlivinginenglandandwalesin2021andchangessince2011/2023-04-03 (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 4NHS England. Primary Care Workforce, England – full-time equivalent (FTE) Nurses, Direct Patient Care and Admin/non-clinical staff. Primary Care Workforce Quarterly Update, 31 December 2023, Experimental Statistics. 2024. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/primary-care-workforce-quarterly-update/31-december-2023 (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 5NHS England. Pharmacy & Medicines Optimisation Dashboard. 2024.

- 6General Pharmaceutical Council. EEA-qualified pharmacists. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2024. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/registration/registering-pharmacist/eea-qualified-pharmacists (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 7General Pharmaceutical Council. GPhC Council meeting on 22 February 2024. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2024. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/news/gphc-council-meeting-22-february-2024 (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 8Royal College of Physicians. Guidance on safe medical staffing. Safe medical staffing. 2018. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/safe-medical-staffing (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 9Royal College of Nursing. Setting appropriate ward nurse staffing levels in NHS Acute Trusts. RCN Policy Unit. 2006. https://www.rcn.org.uk/About-us/Our-Influencing-work/Policy-briefings/pol-1506 (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 10National Quality Board. Supporting NHS providers to deliver the right staff, with the right skills, in the right place at the right time. National Quality Board. 2016. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/nqb-guidance.pdf (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 11Bednall R, White S, Mills E. Pharmacy workforce: matching staffing resource to service demand . Hospital Pharmacy Europe. 2022. https://hospitalpharmacyeurope.com/news/editors-pick/pharmacy-workforce-matching-staffing-resource-to-service-demand/ (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 12Royal Pharmaceutical Society. The Standards for Hospital Pharmacy Services. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2022. https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/setting-professional-standards/hospital-pharmacy-professional-standards/the-standards (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 13Royal College of Emergency Medicine, UK Clinical Pharmacy Association. Joint Position Statement between UK Clinical Pharmacy Association and the Royal College of Emergency Medicine regarding Pharmacists & Pharmacy Services in Emergency Departments . Royal College of Emergency Medicine. 2023. https://rcem.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/RCEM_UKCPA_Joint_Position_Statement_Pharmacists.pdf (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 14The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Critical Care Workforce Development Toolkit. The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. 2024. https://www.ficm.ac.uk/careersworkforcepharmacy/pharmacy-resources (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 15International Pharmaceutical Federation. Medicines reconciliation: A toolkit for Pharmacists. International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). 2021. https://www.fip.org/file/4949 (accessed 3 April 2024)

- 16Cheema E, Alhomoud FK, Kinsara ASA-D, et al. The impact of pharmacists-led medicines reconciliation on healthcare outcomes in secondary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193510. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193510

- 17Redmond P, Grimes TC, McDonnell R, et al. Impact of medication reconciliation for improving transitions of care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010791.pub2

3 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You may also be interested in

From experience it is less a problem of recruitment but more a problem of retention of staff. Also pharmacists being asked to spend an inordinate amount of their time conducting audits which go on to achieve nothing.

I think a challenging aspect of medicines reconciliation is that the Summary Care Record is not accurately updated with recent medication changes from hospital discharge letters or medications prescribed from the private sector or out-of- hours GP prescriptions etc. As a result medicines reconciliations take an inordinate amount of time to complete when an accurate medication history should be readily available via an up to date Summary Care record.

Agreed