c3000 – 1500 BC: Willow is used as a medicine by ancient civilisations like the Sumerians and Egyptians. The Ebers papyrus, an ancient Egyptian medical text, refers to willow as an anti-inflammatory or pain reliever for non-specific aches and pains.

c400 BC: In Greece, Hippocrates administers willow leaf tea, which contains the natural compound from which aspirin is derived, to women to ease the pain of childbirth.

1763: The Royal Society publishes a report detailing five years of experiments on the use of dried, powdered willow bark in curing fevers, submitted by Edward Stone, a vicar in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire.

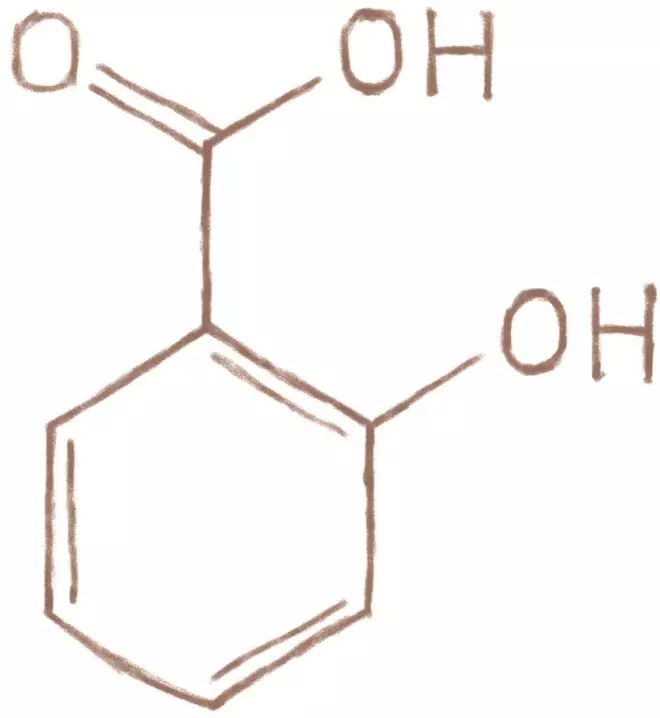

1828: Joseph Buchner, professor of pharmacy at Munich University, Germany, succeeds in extracting the active ingredient from willow, producing bitter tasting yellow crystals that he names salicin.

1830:

Salicin is also found in the meadowsweet flower by Swiss pharmacist Johann Pagenstecher and later by German researcher Karl Jacob Löwig.

1853: French chemist Charles Frédéric Gerhardt determines the chemical structure of salicyclic acid and chemically synthesises acetylsalicylic acid.

1876: The first rigorous clinical trial of salicin finds that it induces remission of fever and joint inflammation in patients with rheumatism (Lancet 1876;1:383).

1897: While working for pharmaceutical company Bayer, German chemist Felix Hoffmann, possibly under the direction of colleague Arthur Eichengrün, finds that adding an acetyl group to salicylic acid reduces its irritant properties and Bayer patents the process.

1899: Acetylsalicyclic acid is named Aspirin by Bayer. The letter ‘A’ stands for acetyl, “spir” is derived from the plant known as Spiraea ulmaria (meadowsweet), which yields salicin, and “in” was a common suffix used for drugs at the time of the first stable synthesis of acetylsalicylic acid.

1950: Aspirin enters the Guinness World Records for being the most frequently sold painkiller.

1971: John Vane, professor of pharmacology at the University of London, publishes research describing aspirin’s mechanism of action (dose-dependent inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis) (Nature New Biology 1971;231:232). He later wins a Nobel prize (1982) for this work, along with Bengt Samuelsson and Sune Bergström.

1974: Data from the first randomised controlled trial of aspirin in the secondary prevention of death from heart attack show a reduction in total mortality of 12% at 6 months and 25% at 12 months but the results are statistically inconclusive (BMJ 1974;1:436).

1991 and 1993: Results from the CPS (cancer prevention study)-II, a large US prospective cohort study, confirm the cancer benefits of aspirin seen in smaller observational studies (NEJM 1991;325:1593 and Cancer Research 1993;53:1322).

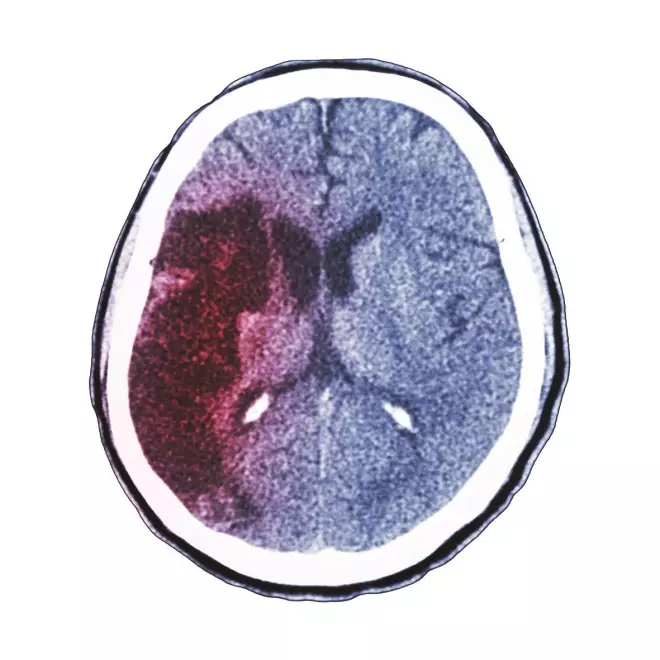

1997: Results from the CAST (Chinese acute stroke trial) study of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke show that aspirin started early in hospital produces a small but definite net benefit (Lancet 1997; 349:1641).

1998: Results from the HOT (hypertension optimal treatment) trial show that aspirin significantly reduces major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients, with the greatest benefit seen in preventing heart attacks. The incidence of non-fatal major bleeds was twice as common (Lancet 1998;351;1755).

2005: Results from WHS (women’s health study), a large, primary-prevention trial among women, suggest that aspirin lowers the risk of stroke without affecting the risk of heart attack or death from cardiovascular causes (NEJM 2005;352:1293). The WHS was conducted by investigators from Harvard Medical School.

2009: A meta-analysis by the ATT (antithrombotic trialists) collaboration suggests that aspirin has substantial overall benefit in secondary prevention but in primary prevention, aspirin is of uncertain net value as the reduction in occlusive events needs to be weighed against any increase in major bleeds (Lancet 2009;373:1849).

2011: A meta-analysis of eight clinical trials finds that, after five years of follow-up, trial participants who took aspirin daily for a mean of four years have a 44% reduced risk of dying from cancer compared with participants who took a placebo (Lancet 2011;377:31).

2013: Follow-up results of the WHS confirm that long-term use of alternate day low-dose aspirin results in a 42% reduction in colorectal cancer incidence, with benefits starting to appear after 10 years. The results also show increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and peptic ulcers (Annals of Internal Medicine 2013;159:77).

2014: A meta-analysis suggests that long-term prophylactic use of aspirin has a favourable benefit–harm profile and leads to a dramatic reduction in the incidence of bowel, stomach and oesophageal cancer (Annals of Oncology, online 5 August 2014).

2015: Results expected from the ARRIVE (aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events) study.

2018: Results expected from the ASPREE (aspirin in reducing events in the elderly) study to determine whether the potential benefits of low-dose aspirin outweigh the risks in healthy people older than 70 years of age.