Abstract

Aim

To compare supplementary prescribing with doctor prescribing of anti-infective agents in haemofiltered patients.

Design

Retrospective study of 6 months before and after introduction of supplementary prescribing.

Subjects and settings

22 bed ICU in a teaching hospital operating electronic prescribing. 145 haemofiltered patients’ drug treatments were assessed.

Results

Before supplementary prescribing, 88 prescriptions (53.7%) were in accordance with the guidelines. After supplementary prescribing was introduced, the doctors’ levels of compliance with the guidelines did not significantly change but all of the 26 prescriptions (100%) issued by the pharmacist supplementary prescriber were appropriate, representing a statistically significant difference (P<0.001).

Conclusion

The pharmacist supplementary prescriber was more likely to adhere to the guideline for drug dosing in haemofiltration in the ICU than the doctors. Supplementary prescribing may improve guideline adherence. However, pharmacists need to be available to prescribe for a greater part of the working week to have a greater impact in this setting.

The introduction of supplementary prescribing provides an opportunity for a new generation of pharmacists to prescribe prescription only medicines for the first time. Following publication in 1999 of “Review of prescribing, supply and administration of medicines”,1 the Department of Health announced plans in 2002 to introduce supplementary prescribing for pharmacists, nurses and midwives. Supplementary prescribing is defined as “a voluntary prescribing partnership between an independent prescriber (a doctor or dentist) and a supplementary prescriber (a pharmacist, nurse or midwife) to implement an agreed patient-specific clinical management plan with the patient’s agreement”.2 The intention was to provide patients with quicker and more efficient access to medicines and to make the best use of the skills of trained professionals.

Previously we have described how a rationale for supplementary prescribing was developed for the intensive care unit, how problems unique to critical care were overcome and how electronic prescribing affected the implementation process.3 The key rationale for supplementary prescribing was that recommendations to rectify inappropriate prescribing were agreed but were then often actioned sub-optimally or not at all. The ICU pharmacist successfully completed the supplementary prescribing course in the first wave. The areas chosen in which to practise supplementary prescribing were dosing in renal failure, gentamicin, vancomycin, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia treatment, steroids in acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock. The scope of this study was for drug dosing in haemofiltration. This area is amenable for investigation because the decision making is predominantly rule-based and, as such, one can clearly judge if the right or wrong dose is chosen. Drugs that are eliminated by the kidney will accumulate in renal failure in a predictable fashion. Kidney dysfunction is common in critically ill patients and once preliminary measures, such as fluid resuscitation and augmentation of urine output with diuretics, have been exhausted then haemofiltration is indicated as a form of renal replacement therapy.

It is important to optimise antiinfective doses in light of renal failure in order to ensure adequate levels are present and to minimise adverse effects. For example, a normal dose of gentamicin can cause nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity in a patient on haemofiltration, and beta-lactam accumulation can cause seizures. A local guideline exists which specifies the appropriate drug doses for patients on haemofiltration. The guideline focuses on anti-infectives since this is the drug group that requires most dose adjustment. This guideline was first written by the ICU pharmacist with the approval of the ICU consultants and microbiologists and was last updated in 2003. The guideline can be viewed from many sources, eg, it can be viewed on the ICU intranet, which has terminals by every bedside, and in the University College London Hospital formulary which is available electronically and in book form.

Haemofiltration-adjusted doses were integrated on to the pick list of the ICU electronic prescribing system. Thus anti-infectives can be prescribed at the preset normal dose or at the haemofiltration dose.

The aim of the study was to compare the prescription of anti-infective drugs that require dose adjustment in haemofiltration prescribed before and after the introduction of supplementary prescribing. The study compared the extent to which the haemofiltration dose adjustment guideline was followed by the ICU doctors and the supplementary prescribing pharmacist. To our knowledge this is the first published study of the impact of supplementary prescribing in a clinical setting.

Method

The study was located at the two local ICUs with a total of 22 beds. Details of drug therapy of those patients undergoing haemofiltration were retrieved from the GE Medical Systems QS Clinical Information Management System (CIMS) database, which electronically records all the clinical data required for this study.

The CIMS database was retrospectively searched to identify all patients who underwent haemofiltration in the six months before and six months after the introduction of supplementary prescribing on 6 May 2004. These drug records were checked for anti-infective agents that require dose adjustment in haemofiltration. The presupplementary prescribing prescriptions were assessed by the ICU pharmacist (RS). In order to improve objectivity, all the post-supplementary prescribing prescriptions were assessed by the senior clinical pharmacist (YJ, who was not a supplementary prescriber but was familiar with critical care) for appropriate compliance with the unit guidelines. If one of the figures was below five, a two-tailed Fisher’s Exact test (z) was calculated to address whether the difference in results reached statistical significance (P<0.05). Otherwise a χ2 test was employed.

Results

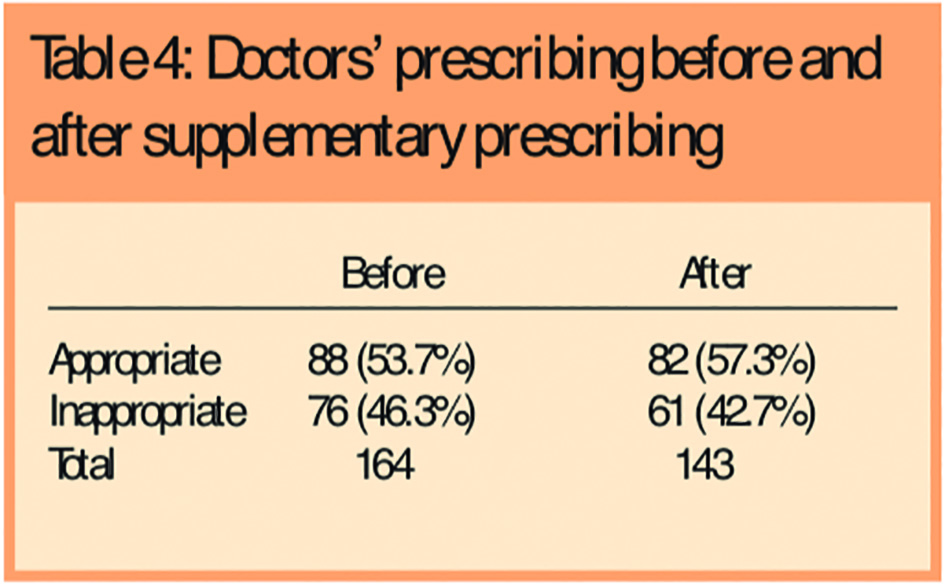

In the six-month data collection period before introduction of supplementary prescribing, 164 prescriptions for anti-infective agents that require dose adjustment in haemofiltration were written by ICU doctors for 89 haemofiltered patients. Of these 88 (53.7 per cent) were in accordance with the guidelines and 76 (46.3 per cent) were not.

In the six months after the introduction of supplementary prescribing, 56 patients were prescribed a total of 169 anti-infective drugs requiring dose reduction. Of these, all 26 of the pharmacist’s prescriptions were judged to be appropriate, while 82 (48.5 per cent) of the doctors’ prescriptions were judged to be appropriate and 61 (36.1 per cent) were judged to be inappropriate. In two cases the supplementary prescriber did not follow the guidelines, but this was judged to have been appropriate by the assessor.

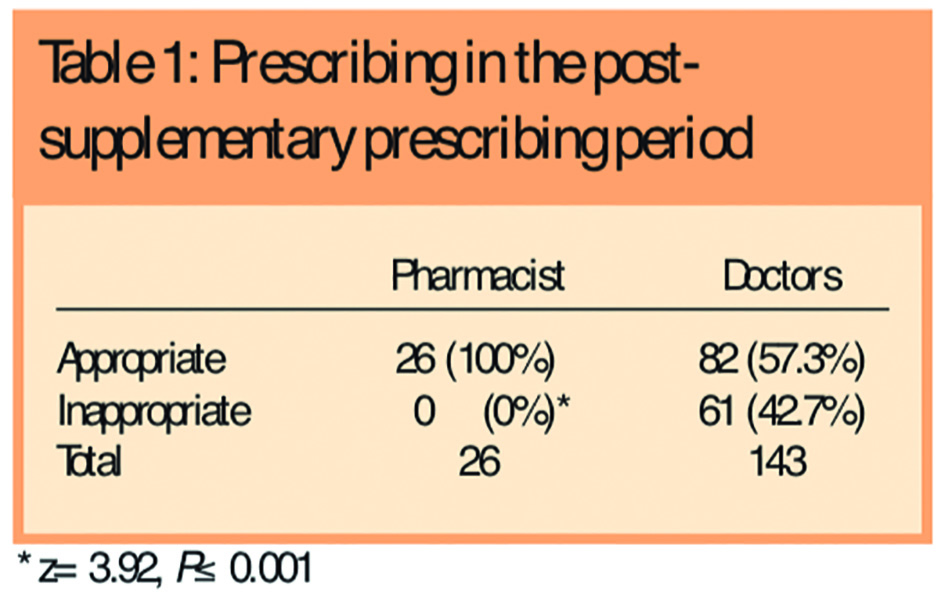

The comparative results of the post-supplementary prescribing period are described in Table 1.

The proportion of appropriate prescriptions attributable to the supplementary prescriber was found to be statistically significantly superior to the doctors (57.3 per cent versus 100 per cent, P<0.001). Comparison of all prescribing before and after the introduction of supplementary prescribing (doctor and pharmacist prescribing combined) did not show any statistical difference (χ2=3.2, P=0.07, see Table 2), although there was a trend suggesting an improvement.

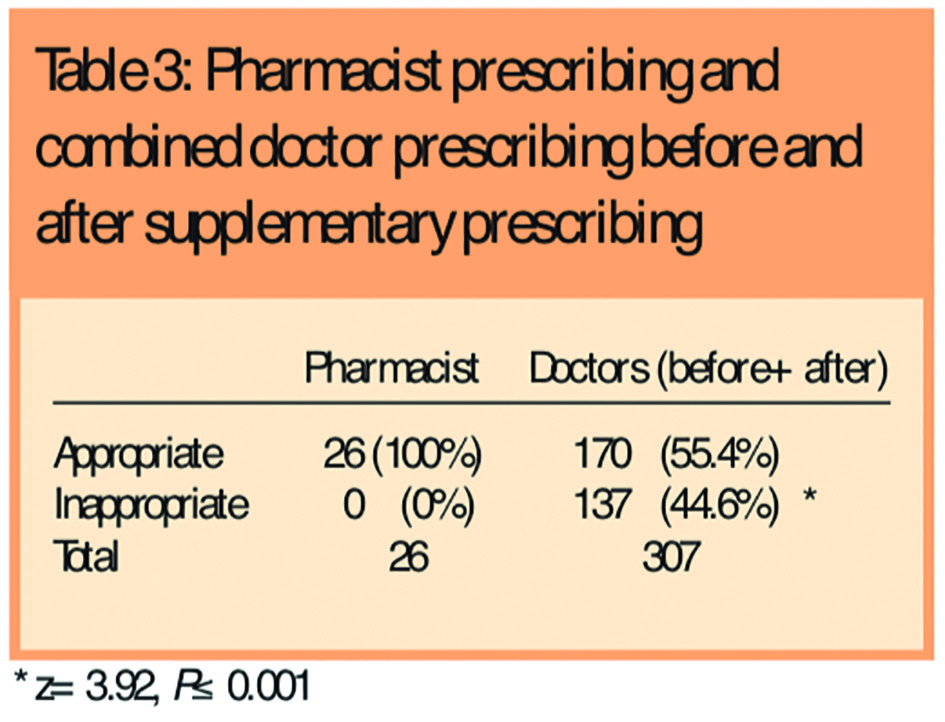

Comparison of the proportion of appropriate prescriptions written by the supplementary prescriber versus the combined doctor prescribing before and after supplementary prescribing (Table 3), revealed that the pharmacist’s prescribing was statistically significantly more in accordance with the guidelines than the doctors’ (55.4 per cent versus 100 per cent, P<0.001).

There was no difference in doctors’ prescribing before and after the introduction of supplementary prescribing (Table 4).

Conclusion

Compliance with the haemofiltration drug dosing guideline in this ICU setting before supplementary prescribing was introduced, was found to be 53.7 per cent. This is despite a degree of electronic decision-support and guidelines available. This high degree of error justifies the suitability of this area for supplementary prescribing, since the previous performance was sub-optimal. These figures represent the standard system of doctor prescribing, with the pharmacist suggesting guideline compliance on daily ward visits. The introduction of supplementary prescribing provided an outlet for a new type of prescriber who was conversant with the guidelines and was motivated to implement them.

This study found that the prescriptions written by the supplementary prescriber were in accordance with the guidelines to a substantially greater extent than the prescriptions written by doctors. Although not achieving statistical significance there was a trend suggesting an improvement in global prescribing in this area following the introduction of supplementary prescribing. This may have occurred because of the raised profile of these issues at the time, although the rate of appropriate prescribing by the doctors did not improve after the introduction of supplementary prescribing. Overall the pharmacist prescribed appropriately in all cases but the doctors did so in 55.4 per cent of cases (P<0.001).

Few interventions in critical care have been shown to improve mortality or outcome and it is unrealistic to be able to demonstrate that supplementary prescribing will improve these aspects of care or indeed cost or length of stay. Perhaps a more pragmatic aim is to endeavour to use supplementary prescribing as a method to implement evidence-based medicine. It has been noted in a systematic review4 that outcomes for patients and organisations improve if clinical practice in health care is evidence-based, and if evidence-based clinical practice guidelines are used. Furthermore, it is reported that primary care doctors and nurses rarely access and use explicit evidence from research or other sources directly, but rely on “mindlines”, ie, collectively reinforced, internalised, tacit guidelines.5 Our results suggest that supplementary prescribing may be used as a measure to increase adherence to clinical guidelines and this is a worthwhile endeavour in its own right.

The medical and nursing staff were extremely supportive of supplementary prescribing and there were no issues raised or comments made that reflected adversely on the venture; they were merely surprised that the scope was so limited.

This study demonstrated that supplementary prescribing can be used to harness pharmacists’ expertise to improve prescribing in acute care. Pharmacists have a unique focus on medicines management and are highly motivated to see guidelines, which in many cases they have written, put into practice. However, it highlights that to impact on the overall prescribing quality, pharmacists need to be available to prescribe for a greater part of the working week, particularly in the critical care setting.

This paper was accepted for publication on 17 March 2005.

About the authors

Robert Shulman, Clin Dip Pharm, MRPharmS, is ICU pharmacist, University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust

Yogini Jani, MSc, MRPharmS, is senior clinical pharmacist, University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust

Correspondence to Robert Shulman, Pharmacy Department, UCL Hospitals, Mortimer Street, London W1T 3AA (e-mail robert.shulman@uclh.nhs.uk)

References

- Department of Health. Review of prescribing, supply and administration of medicines (Crown Report). London:Department of Health; 1999.

- Department of Health. Supplementary prescribing by nurses and pharmacists with the NHS in England: a guide for implementation. London: Department of Health; 2003.

- Shulman R. Is there a role for supplementary prescribing in acomputerised ICU? The Pharmaceutical Journal 2004;273:263–5.

- Bahtsevani C, Uden G, Willman A. Outcomes of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 2004;20:427–33.

- Gabbay J, le May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. BMJ 2004;329:1013–20.