- The role of pharmacy in antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) has evolved significantly since the beginning of the 21st century.

- In the UK, antimicrobial pharmacists play an essential role in AMS; the role is well established and recognised, particularly in secondary and tertiary care.

- All pharmacy professionals across all sectors can significantly contribute to AMS through a number of activities, such as providing clinical advice, developing guidelines and delivering education and training to other healthcare professionals and the public.

- Globally, pharmacy teams have shown the importance of being recognised as part of multidisciplinary AMS or management teams, providing significant contribution to evidence-based decision-making.

- There is scope to develop pharmacy roles further across all sectors of practice, providing that appropriate integration and infrastructural support is assured.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major public health concern with profound impact on both global healthcare and economy. There is no single straightforward approach to tackling AMR, although antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) is widely accepted as a good place to start. AMS can be described as a set of defined, multifaceted, structured and integrated measures to ensure appropriate and safe use of antimicrobials in order to improve clinical outcomes and minimise further development of AMR. There is significant variation in global patterns of AMR and these trends are continuously evolving; therefore, healthcare teams have had to evolve and adapt, with pharmacy increasingly leading and participating in local, national and global AMS activities. A large number of antimicrobial pharmacists in the UK play an essential role in local, regional and national multidisciplinary antimicrobial advisory committees and management teams. A better understanding of the range of pharmacy skills and activities undertaken as part of AMS would be valuable to further develop what pharmacy offers and explore opportunities to increase its impact across all settings and scopes of practice. This article aims to summarise the published literature on the role of pharmacists and pharmacy teams in AMS and the impact of their activities.Methods

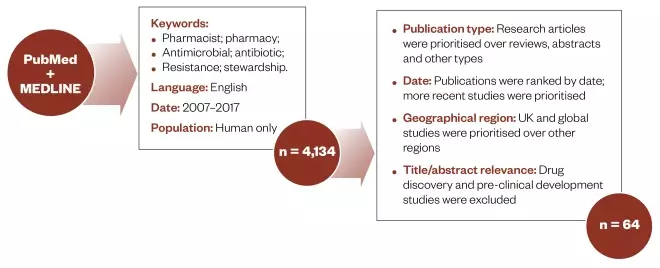

A search of national and international publications was undertaken using the following databases: MEDLINE (Ovid) and PubMed, for articles published in English between 2007 and 2017. The following keywords were used: [pharmacist(s) OR pharmacy(ies)] AND [antimicrobial(s) OR antibiotic(s)] AND [resistance OR stewardship] and only studies involving human population were eligible for inclusion. Literature relating to AMR and AMS was identified, analysed and summarised. Primary focus was given to studies undertaken in the UK and these were compared with international research. Key citations on the topic were also considered in this review (see Figure 1).Results

After excluding duplicates, a total of 4,134 publications were identified through online database searches (see results of data searches in the supplementary information online). These were categorised according to relevance, general theme(s) and geographical location of the study and authors, resulting in 64 publications that were selected for further analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Methodology

Summary of the method used to identify literature about the role of pharmacy in antimicrobial stewardship.

| Themes | Number of articles | Percentage of articles |

|---|---|---|

| †The total number of references do not add up because a single paper may cover more than one of the above themes. | ||

| Aims of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) and the role of pharmacy | 18 | 28 |

| Key AMS strategies in secondary and tertiary care (hospital settings) | 33 | 52 |

| Key strategies in primary and community care (GP surgeries, community pharmacies, care homes, etc.) | 16 | 25 |

| Pharmacy as core part of multidisciplinary AMS teams | 13 | 20 |

| Education and training about antimicrobial resistance and AMS | 15 | 23 |

| Developments in technology enabling innovation in AMS | 10 | 16 |

| Total number of references†| 64 | 100 |

Discussion

Aims of AMS and the role of pharmacy

Pharmacy’s contribution to AMS has significantly evolved over the course of the 21st century[1],[2] . Although microbiologists and infection-specialist physicians are conventionally responsible for providing advice on management of infection in the UK, many pharmacists in clinical practice have now established roles complementing the expertise in multidisciplinary AMS teams, particularly in secondary and tertiary care[3] . A summary of the roles of pharmacy can be found in Box 1.- Development, review and implementation of AMS guidelines and policies;

- Clinical advice to optimise antimicrobial prescribing and use;

- Monitoring, audit and feedback;

- Education and training of healthcare professionals, patients and the general public;

- Development, testing and implementation of digital AMS platforms, including electronic prescribing, smartphone apps and e-learning;

- There is a wider scope to develop pharmacy roles further providing that appropriate integration and infrastructural support is assured.

- Infection prevention and control;

- Antimicrobial prescribing;

- Education and training of healthcare professionals and the general public;

- Discovery and development of new medicines, treatments and diagnostics;

- Better access to and use of surveillance data;

- Research;

- Strengthening collaboration[4] .

Key strategies in secondary and tertiary care

Implementation of AMS initiatives in secondary care is essential; they can help optimise antimicrobial therapy and improve patient outcomes while reducing the burden of hospital-acquired infections, the spread of AMR and consequent healthcare costs[9],[19] . Several strategies have been developed and implemented in the UK over the years, with large contributions from antimicrobial pharmacists[8] . Between 2003 and 2006, the UK Department of Health (now the Department of Health and Social Care) invested significant funding in this area, enabling the expansion and emergence of new pharmacy roles[2],[6] coinciding with the development of more defined AMS action plans across the UK[2],[13] . Since then, the role of antimicrobial pharmacists has become well established, alongside their formal recognition as part of multidisciplinary AMS teams in secondary and tertiary care settings in England[8],[17],[20] . Similar roles have also evolved in Scotland[2],[5] , Wales and Northern Ireland[2] . In 2011, a national electronic questionnaire disseminated to antimicrobial pharmacists and chief pharmacists from 153 acute hospitals in England (n=120; 78% response rate) revealed around a 1.5-fold increase in the number of specialist antimicrobial pharmacists (n=175) compared with a similar evaluation undertaken in 2005. All hospitals that responded to the survey reported having at least one specialist antimicrobial pharmacist, with 35% having two or more in post; 16% of these roles were full-time[6] . These findings were consistent with similar studies undertaken since then, describing the role of antimicrobial pharmacists as an essential part of the AMS team[3],[20] . Initial AMS activities undertaken by antimicrobial pharmacists in secondary care mostly focused on reducing the incidence and prevalence of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), aligned to national priorities and defined targets[2],[21] . Voluntary reporting of HAIs later became mandatory, driving further development and implementation of AMS programmes in a number of healthcare organisations[2] . Today, the role of antimicrobial pharmacists has evolved dramatically, as shown by a 2011 evaluation that reported the range of AMS activities was greater compared with a 2005 analysis, with 95% of the surveyed hospitals making systematic use of empirical guidance formularies and surgical prophylaxis guidelines[6] . Further activities pharmacy professionals in secondary care undertake include: prescription reviews to improve antibiotic prescribing and use[8],[17] , audits[17],[20],[22] , feedback with promotion of safe and appropriate use of antimicrobials[17],[20],[23] and development of antimicrobial policies[20] . There is, however, an opportunity to expand these roles more widely across sectors and scopes of practice. In 2007, a new antibiotic ‘care bundle’ — the grouping together of key elements of care to provide a systematic method to improve and monitor the delivery of care processes — was proposed as a measure to improve prescribing for treatment and prophylaxis of infectious disease[15],[24] . As with other care bundles successfully implemented at that time, a number of key recommendations were proposed, including appropriate specimen collection and initial antibiotic selection, followed by a daily review for de-escalation, intravenous–oral switch or stopping the antibiotic as required[15],[24] . Pharmacy’s contribution to the design, development and implementation of antimicrobial care bundles has been previously documented[25],[26] . In line with these initial recommendations, the evidence-based guidance ‘Start Smart — Then Focus’ was published in 2011 by Public Health England (updated in 2015)[27] . Specifically designed for use in secondary care, the guidance includes recommendations from NICE and other relevant evidence to help prevent and control infectious diseases[27] . Recommendations include an empirical choice of antibiotic (narrow spectrum whenever possible) at the start of the treatment, followed by a ‘focus’ stage review at 48 hours, and therapy optimisation once laboratory results have confirmed the causative agent. Five options can then be considered, including: ‘stop’ therapy if there is no evidence of infection; ‘switch’ from intravenous to oral; ‘change’ antimicrobial (preferably to a narrower spectrum, with broader spectrum use only if absolutely essential); ‘continue’ therapy with review at 72 hours; or ‘outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy’. The principles of Start Smart — Then Focus have also significantly contributed to the improvement and harmonisation of AMS across hospital trusts in England[7],[19] . One of the main AMS initiatives in hospital settings is the attempt to significantly minimise antibiotic-induced selective pressure by limiting the use of macrolides and ‘4C’ antibiotics (cephalosporins, co-amoxiclav, clindamycin and fluoroquinolones), particularly to reduce the incidence of HAIs such as MRSA and CDI[2],[21],[28],[29],[30] . In addition to this intervention, the implementation of infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, such as hand hygiene, hospital environment inspections and MRSA admission screening, as well as mandatory surveillance of HAIs[29],[30] , have helped reduce the levels of antibiotic prescribing and hospital- and community-associated infections[28],[29] . Moreover, as part of the national UK AMS strategy, focus has also been given to other antimicrobials, such as antifungals[31] . Research studies in this area have similarly outlined the importance of working across disciplines to ensure the focus stage is in effect with consequent improvement in patient management and reduced costs[31] . Despite these recommendations, a number of evaluations of using Start Smart — Then Focus suggest that many organisations do not necessarily implement or reinforce interventions; however, most hospital policies recommend reviewing antimicrobial prescriptions and complying with AMS indicators[3],[19],[23],[32] . It has been suggested that a poorly implemented focus stage is likely to increase the inappropriate use of antimicrobials, particularly of broad-spectrum antibiotics, with concomitant increased risk of emergence of HAIs[11],[32] . A Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) local retrospective audit for prescription of antibiotics for urinary tract infections, undertaken between July and August 2013, highlighted the need for improvement in AMS — particularly in compliance with local guidelines and appropriate documentation of antibiotic prescriptions (stop/review date)[23] . The implementation of education and training sessions to the multidisciplinary team, as well as proactive checks by antimicrobial pharmacists, were shown to be effective interventions to improve AMS over a short period of time[23] . The methods adopted for evaluation and reporting of AMS activities in hospitals can be variable, as there is no universal system and a number of different approaches have been documented[2],[12] ,[22],[33],[34],[35] . In the UK, the web-based Antimicrobial Self-Assessment Toolkit was developed and optimised to assess AMS interventions in acute hospitals. First launched in 2010, the project was led by the Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection and extensively tested in the hospital setting by a national pharmacy reference group. The evidence-based audit toolkit comprises seven domains for action; domain six was specifically designed to ensure maximum use of antimicrobial pharmacists[36] . Since its launch, this online system has been continuously tested and improved to incorporate enhanced features that support the role of antimicrobial pharmacists and multidisciplinary AMS teams[36],[37],[38],[39] . In an attempt to harmonise the use of electronic and digital systems to assist AMS in secondary care, a number of approaches have been evaluated; these are further discussed in the section ‘Development in technologies enabling innovation in AMS’.Key strategies in primary and community care

The contribution of pharmacy professionals in primary and community care (e.g. care and nursing homes) can be instrumental, owing to their medicines expertise together with the service distribution, accessibility and activity outreach. The role of community pharmacy services as the first port of call for patient advice and management for minor ailments has been particularly encouraged in recent years[4],[8] . As with secondary care, the development and implementation of AMS programmes in primary care and in community settings has been essential. Although AMS activities and evaluations have become more common in this sector in recent years, antimicrobial pharmacy roles tend to be less established compared with the hospital environment[8] . A 2014 evaluation by Ashiru-Oredope et al. reported that only 5% of primary care organisations in England (211 Clinical Commission Groups surveyed; 39% response rate) had an antimicrobial pharmacist in post[3] . Several factors can affect the success rates of AMS programmes in primary and community care, including governance, management, financial support and individual practice[5],[8] . It has been reported that 80% of all antibiotics are prescribed in primary care, with substantial variation in prescribing rates and trends depending on location, time and individual circumstances[8],[9],[40] . Similarly to secondary care, initiatives and resources have been developed in an attempt to promote the appropriate use of antimicrobials, particularity to reduce the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics as part of AMS initiatives in primary care[28],[30] . Hosted by the Royal College of General Practitioners, the national AMS TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education Tools) initiative contains a range of resources to promote and support safe antibiotic prescribing and use in primary care, including infectious diseases management guidelines and educational tools. Ashiru-Oredope et al. evaluated the implementation of the AMS interventions recommended by the TARGET toolkit and found that, although most healthcare organisations review the recommendations, many do not necessarily reinforce them; only 13% of CCGs (11 of the 211 total) that responded to the electronic survey proceeded to develop an action plan following guidance[3] . One important advancement in line with AMS recommendations in primary and community care is the development and implementation of quick and reliable diagnostic tests, with support for diagnostics in primary care being less established compared with secondary care[8] . For example, the use of point-of-care C-reactive protein testing aims to facilitate the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infections and reduce antibiotic prescribing[41] . Research into the advantages and disadvantages of diagnostic testing across the UK and European Union (EU), including the views of pharmacists and the potential implementation of diagnostic testing in community pharmacy, has emphasised the potential cost-effectiveness of testing, as well as the key role that pharmacies have in AMS initiatives[42] . Challenges associated with patients and the general public have also been reported in this sector[8] . A retrospective cross-sectional study (2012–2013 data) linking patient satisfaction with antibiotic prescribing in general practice in England suggested that patients were less satisfied in practices with more prudent antibiotic prescribing[43] . The reasons for this included antibiotics making patients feel better, being a proof of illness and making the trip to the doctor worthwhile[40] . In addition, the potential risks and concerns of pharmacy availability of over-the-counter antibiotics have been outlined[44] . One area of expansion within the healthcare sector focuses on the development of online platforms that make antibiotics and other medicines more easily available to the public. It has been shown that there is no standardisation between the different online pharmacies, which may put patients’ safety and AMS efforts at risk, indicating the need for regulation of online antibiotic supplies[45] . Timely and effective patient and public education is essential to ensure that this standardisation is translated correctly, without increasing patient risk or pressure to prescribe antibiotics, especially for coughs and colds, which often do not require antibiotic treatment. Understanding the views of patients and the general public in relation to antibiotics and their interpretation of antibiotic resistance can be crucial to increasing engagement and success of AMS programmes[40],[46] . The results of a 2015 questionnaire disseminated to 145 hospital outpatients in a large teaching hospital in England reported a considerable level of public awareness about the concerns around antibiotic misuse, with 99% of the respondents answering correctly to a specific question about MRSA. By contrast, the definitions of AMR and AMS have been shown to be less clear (85% and 72% incorrect replies; n=122 and 96, respectively)[46] . A similar study published in the same year suggested that many people do not understand these concepts and, therefore, it would be of benefit if the language used to communicate AMR and AMS to the public was simplified[40] . Moreover, more co-ordinated antibiotic prescribing practices in order to minimise variation could potentially better clarify the message delivered to the public[8],[40] . In alignment with other sectors of practice, multifaceted approaches (as opposed to single, direct approaches) have been shown to be more effective in enforcing AMS principles in primary care. For example, a programme in Derbyshire, UK, comprising of a range of interventions such as the development of evidence-based treatment guidelines and support resources, as well as educational sessions delivered to healthcare professionals, patients and local schools, was shown to decrease antibiotic prescribing over the initiative’s four-year period[47] . A more comprehensive understanding of the wider AMS landscape in primary care services and the community has proven to be challenging; many of the activities undertaken have not been systematically evaluated or reported, the levels of engagement have been reported to be low, and the available evidence can therefore be considerably divergent[3],[8] . As a result, further integration of these activities would be of benefit to improve AMS outcomes.Pharmacy as core part of multidisciplinary AMS teams

A body of evidence suggests that there is great benefit from the establishment of multidisciplinary AMS teams[3],[5],[6],[8],[17],[23],[31],[48],[49] . All healthcare professionals (including pharmacists), commissioning and provider organisations, service users and the public should work together to develop and implement effective AMS strategies[18] . At present, the great majority of hospitals that have antimicrobial management or stewardship teams often include at least one antimicrobial pharmacist[6],[20],[23] . Their range of activities include regular audits[17],[20] , prescription reviews to improve antibiotic prescribing and use[17],[23] , systematic use of empirical guidance formularies and surgical prophylaxis guidelines [6] , feedback with promotion of safe and appropriate use of antimicrobials[17],[20] and development of antimicrobial policies[20] . The multidisciplinary approach to AMS has also been extended to education and training in the UK. Emphasis has been given to the need for a more structured and integrated education strategy at national level, incorporating all relevant disciplines with an essential role in patient outcomes, including pharmacy teams and non-medical prescribers[48],[50] . Cross-sector multidisciplinary actions can also be advantageous, with antimicrobial pharmacists proving to be central to the implementation of AMS principles both across primary and secondary care. The recognised impact of the wider pharmacy role includes improved patient outcomes and reduced healthcare costs[31] , although further research would be useful in order to evaluate more specific outcomes and to describe best practice throughout the patient’s care journey. AMS teams are common in England[17],[20] with similar roles evolving in Scotland[5] , Wales and Norther Ireland[2] . There is, however, wide scope for continuous development, improvement and further integration of pharmacy roles at national and international level.Education and training about AMR and AMS

Delivery of AMR and AMS education and training to healthcare professionals and the general public has been identified as essential[4],[23] , and is a key area where pharmacy has contributed significantly[2] . Most undergraduate and relevant postgraduate courses across the UK provide education and training in a number of AMR and AMS principles. However, the need for an improvement in education and training of healthcare professionals, including pharmacy, has been recognised[4] , with further standardisation, multidisciplinary and integration recommended across higher education institutions and taught courses[50],[51],[52] . Furthermore, the importance of additional training in subjects such as genomics, bioinformatics and advances in diagnostic testing has been highlighted[1] . A 2013 mapping of undergraduate teaching of AMS principles to future healthcare professionals (including medical, dental, pharmacy, nursing and veterinary) highlighted that the majority of AMS principles were being taught across higher education institutes; this included subjects such as infection prevention and control, specimen collection and testing, and safe antimicrobial prescribing. However, the need for a standardised and integrated undergraduate curriculum was identified[51] . In 2013, a ‘five-dimension’ antimicrobial prescribing and stewardship competency framework was developed for the first time by an independent multiprofessional group, led by the Department of Health’s Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection. The collection of available evidence, including regulatory and guidance documents and national AMS guidance for primary and secondary care, resulted in this framework, which represents a step toward the harmonisation of education and training of healthcare professionals[53] . With regards to postgraduate training on AMS, there is a reported need for increasing the depth of and engagement with AMS principles across disciplines, as there is still poor evidence on their precise application into practice, especially in primary care[52] . In an attempt to improve antimicrobial prescribing practices in primary care, a range of educational resources were made available through the TARGET toolkit[3],[54] . In 2014, a group of antimicrobial pharmacy experts developed an expert curriculum to support the professional development and the role of pharmacists specialising in this area. The curriculum describes pharmacy skills and activities undertaken as part of AMS, and has been endorsed by a number of organisations, including the Royal Pharmaceutical Society — the professional leadership body for pharmacists in Great Britain[55] . Integrated learning of core AMS concepts across all healthcare professions could be better reinforced, particularly at postgraduate level, to ensure efficient implementation and delivery in practice[52] . Moreover, it has been suggested that education and training on antimicrobial prescribing and use should not only be delivered to prescribers, but to all healthcare professionals with essential roles in patient care[50] . Worldwide initiatives and open access to AMS resources for all healthcare professionals have proven to be essential and can have a major impact on the global fight against AMR. In response to the demand from an educational perspective, a joint venture between the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and the University of Dundee developed a comprehensive open online course, available worldwide and comprising free online training on management of infectious diseases and safe use of antibiotics. This initiative reached a total of 33,000 learners in 163 countries between October 2015 and June 2016[56] . The European Antibiotic Awareness Day (EAAD) is an annual public health initiative held on 18 November to raise awareness of AMR by engaging healthcare professionals and the general public and promoting appropriate use of antimicrobials[2],[57] . Since it started during the winter of 2007/2008, the UK has actively promoted and participated in EAAD activities together with other EU member states[2] . The campaign has wider participation from the government, hospitals, GP practices, pharmacies, higher education institutions, professional societies and many other organisations. It builds on the principle that appropriate education is crucial for both healthcare professionals and the general public. Key messages include appropriate management of coughs and colds with prudent antimicrobial use and the importance of seeking advice from the pharmacist or doctor when in doubt[57] . Reflections on the initial 2008 EAAD campaign suggested that the sole use of information posters was not sufficient to change behaviours. To address these findings, other alternatives were explored in subsequent years, including the development of more interactive resources, messages and promotional videos. In 2009, the UK-led ‘e-bug’ website, comprising free interactive learning resources, was launched. The project was aimed particularly at children aged 7–15 years and their teachers, and provided them with educational resources to support learning about microbes and prevention of infectious diseases[58] . During the EAAD 2010 campaign, a greater focus was given to antimicrobial prescribers and prescribing leads, as well as healthcare professionals in general, including pharmacists, surgeons, dentists, veterinary surgeons, paediatricians, microbiologists and infection control teams. The campaign included the development of an evidence-based AMS toolkit (Antibiotic Stewardship, Prevention of Infection and Control), which was launched in 2012 and contained resources for primary care professionals to raise public awareness. Furthermore, recommendations were made to improve AMR/AMS education of healthcare professionals, both at undergraduate and postgraduate levels, particularly in subjects such as hygiene, IPC procedures and appropriate use of antimicrobials[58] . One of the aspects promoted during the 2012 EAAD campaign was the Start Smart — Then Focus guidance for secondary care and the TARGET toolkit for primary care. Healthcare professionals were encouraged to use these resources and to actively engage with AMS activities[54] . EAAD initiatives during 2013 focused on peer education for students and educators; both groups were trained to deliver education to their peers on hygiene and appropriate use of antibiotics. For healthcare professionals, successful activities included the Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children project, aimed at increasing evidence and education for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in children. In addition, the ‘When Should I Worry?’ booklet for primary care was developed to provide information about respiratory tract infections in children[59] . As part of the 2014 EAAD, the Antibiotic Guardian campaign was launched to raise awareness of AMR and increase commitment to AMS by all healthcare professionals and the general public. At the time of publication of this article, this online pledge-based system had received more than 60,858 contributions.Development of technology enabling innovation in AMS

Advancements in health technologies have enabled the development of novel systems to support the implementation of AMS principles and improve antimicrobial prescribing, surveillance, intervention and subsequent patient outcomes. Antimicrobial pharmacists, in particular, have had an essential role in the development, improvement and implementation of technology in the healthcare system[1] . Since 2013, additional funds have been invested to improve NHS digital and to develop electronic prescribing (e-prescribing) and medicines administration software[19] for implementation in many organisations in the UK and globally[1],[60] . However, there is potential for a wider application of these systems to further implement and promote AMS programmes[60] . In Scotland, in line with the 2008 recommendation of the Scottish Antimicrobial Management of Resistance Action Plan (updated in 2014), a new infection intelligence platform hosted within the national health data repository, was developed. This initiative was led by the multidisciplinary Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group with the participation of stakeholder groups, including pharmacy. The new platform aims to improve AMS by facilitating national data collation and analysis, and aiding evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice[10] . A study by Hand et al. sought the views of healthcare professionals on e-prescribing systems and demonstrated the importance and utility of several software functionalities; these include indication prompts, treatment protocols, drug-indication mismatch alerts, dose and allergy checkers, interaction checkers, prolonged course alerts, and ‘soft-stop’ functionality. Respondents to this evaluation study were in their majority specialist infection pharmacists practicing in secondary care settings[60] . However, research has shown that e-prescribing systems are used in different manners across organisations[19],[35] , which means better standardisation of electronic systems is needed to improve outcomes and to mitigate prescribing-related risks, such as AMR[1],[35] . The use of online AMS toolkits and checklists has also been explored. For example, the Antimicrobial Self-Assessment Toolkit aims to facilitate self-assessment of AMS across seven domains of standards and recommendations, including: antimicrobial management (structures and lines of responsibility and accountability); operational delivery (AMS standards); risk assessment (treatment and safety); clinical governance assurance (adherence to standards assessed by audit and feedback); education and training (for all healthcare professionals using antimicrobials); antimicrobial pharmacists (ensuring their optimum use), and patients, carers and the public (information and advice)[36] . Innovation in health technology has also enabled the development of AMS smartphone and desktop applications (apps) for healthcare professionals and the general public. Documented examples include apps to support pharmacists and microbiologists to monitor local bacterial resistance profiles[61] , disseminate AMS policy and guidelines to the point of care[62],[63] , increase AMS adherence[62] , support clinical decision-making[62],[63] , facilitate clinical calculations[63] , and optimise antimicrobial prescribing[64] . Evaluation of uptake and acceptability among clinicians, including pharmacy teams, measured through focus group feedback, questionnaires, app downloads and use by healthcare professionals, suggests that these apps can be popular, especially among junior practitioners[63] . Evidence also suggests that patients welcome the use of technology by their physicians during consultation[64] . From a public and patient perspective, mobile apps can be particularly useful to find information about the aetiology, symptoms and management advice for infectious diseases. A number of studies have, however, outlined some of the risks and safety implications on the use of these apps by the public, including the inconsistency and lack of governance for medical apps[64] .Conclusion

This article provides a general outline of the role of pharmacy on AMS, with particular focus on activities in the UK. Regardless of setting or scope of practice, all healthcare professionals (including all pharmacy teams) should work together to use their expertise to help reduce AMR in a more co-ordinated manner. There is also the need to deliver more structured and integrated cross-sector education and training to minimise variation in practice and to better clarify the message delivered to patients and to the general public. Following a basic literature search strategy, this study does not intend to be a comprehensive collation of relevant literature, but rather an overview of a number of relevant publications in this area of practice. Nevertheless, this article outlines some of the current and potential roles of pharmacy in the global fight against AMR.Nominate an early-careers researcher today for the OPERA23 award

Help us in our search for outstanding early-career researchers who are accomplishing great things in pharmacy and pharmaceutical science. For entry criteria and details on how to nominate a colleague, click here.References

[1] Davies SC. Annual report of the chief medical officer, volume two, 2011: infections and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. Department of Health (London), 2013. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/138331/CMO_Annual_Report_Volume_2_2011.pdf (accessed June 2018)

[2] Gilchrist M, Wade P, Ashiru-Oredope A et al. Antimicrobial stewardship from policy to practice: experiences from UK antimicrobial pharmacists. Infect Dis Ther 2015;4(Suppl 1):51–64. doi: 10.1007/s40121-015-0080-z

[3] Ashiru-Oredope D, Budd EL, Bhattacharya A et al. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship interventions recommended by national toolkits in primary and secondary healthcare sectors in England: TARGET and Start Smart — Then Focus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71(5):1408–1414. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv492

[4] Department of Health. UK 5-year antimicrobial resistance strategy 2013 to 2018. Department of Health (London), 2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-5-year-antimicrobial-resistance-strategy-2013-to-2018 (accessed June 2018)

[5] Colligan C, Sneddon J, Bayne G et al. Six years of a national antimicrobial stewardship programme in Scotland: where are we now? Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2015;4:28. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0068-1

[6] Wickens HJ, Farrell S, Ashiru-Oredope D et al. The increasing role of pharmacists in antimicrobial stewardship in English hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(11):2675–2681. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt241

[7] Ashiru-Oredope D, Sharland M, Charani E et al. Improving the quality of antibiotic prescribing in the NHS by developing a new antimicrobial stewardship programme: Start Smart — Then Focus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67(Suppl 1):i51–63. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks202

[8] Public Health England. Behaviour change and antibiotic prescribing in healthcare settings — literature review and behavioural analysis. Public Health England (London), 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antibiotic-prescribing-and-behaviour-change-in-healthcare-settings (accessed June 2018)

[9] Public Health England NHS. Patient safety alert — stage two: resources addressing antimicrobial resistance through implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship programme. NHS England; 2015. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/psa-amr-stewardship-prog.pdf (accessed June 2018)

[10] Bennie M, Malcolm W, Marwick CA et al. Building a national infection intelligence platform to improve antimicrobial stewardship and drive better patient outcomes: the Scottish experience. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(10):2938–2942. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx229

[11] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial stewardship: prescribing antibiotics. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt9 (accessed June 2018)

[12] Ashiru-Oredope D & Hopkins S, on behalf of the English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilization and Resistance Oversight Group. Antimicrobial stewardship: English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilization and Resistance (ESPAUR). J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(11):2421–2423. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt363

[13] Nathwani D, Sneddon J, Malcolm W et al. Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG): development and impact of the Scottish National Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2011;38(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.02.005

[14] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng15 (accessed June 2018)

[15] Cooke FJ, Matar R, Lawson W et al. Comment on: antibiotic stewardship — more education and regulation not more availability? J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(3):598. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp481

[16] HM Government & Wellcome Trust. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. 2014. Available at: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf (accessed June 2018)

[17] Fleming A, Tonna A, O’Connor S et al. Antimicrobial stewardship activities in hospitals in Ireland and the United Kingdom: a comparison of two national surveys. Int J Clin Pharm 2015;37(5):776–781. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0114-3

[18] NICE antimicrobial stewardship: right drug, dose, and time? Lancet 386(9995):717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61522-7

[19] Ladenheim D, Cramp E & Patel N. Are current electronic prescribing systems facilitating antimicrobial stewardship in acute National Health Service hospital trusts in the east of England? J Hospital Infection 2016;94(2):200–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.07.017

[20] Tonna AP, Gould IM & Stewart D. A cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial stewardship strategies in UK hospitals. J Clin Pharm Ther 2014;39(5):516–520. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12181

[21] Nathwani D, Sneddon J, Patton A & Malcolm W. Antimicrobial stewardship in Scotland: impact of a national programme. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2012;1:7. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-1-7

[22] Cooke J, Stephens P, Ashiru-Oredope D et al. on behalf of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Subgroup of the Department of Health’s Advisory Committee for Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare-Associated Infection. Antibacterial usage in English NHS hospitals as part of a national Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme. Public Health 2014;128(8):693–697. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.06.023

[23] Oppenheimer M & Rezwan N. CQUIN audit for prescription of antibiotics for urinary tract infections in an acute medical assessment unit. BMJ Open Qual 2015;4(1):u208446.w3374. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u208446.w3374

[24] Cooke FJ & Holmes AH. The missing care bundle: antibiotic prescribing in hospitals. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007;30(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.03.003

[25] Coll A, Kinnear M & Kinnear A. Design of antimicrobial stewardship care bundles on the high-dependency unit. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34(6):845–854. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9680-9

[26] Toth NR, Chambers RM & Davis SL. Implementation of a care bundle for antimicrobial stewardship. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2010;67(9):746–749. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090259

[27] Public Health England. Start Smart — Then Focus: antimicrobial stewardship toolkit for English hospitals. Public Health England (London), 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-stewardship-start-smart-then-focus (accessed June 2018)

[28] Lawes T, Lopez-Lozano J-M, Nebot CA et al. Effect of a national 4C antibiotic stewardship intervention on the clinical and molecular epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infections in a region of Scotland: a non-linear time-series analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17(2):194–206. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30397-8

[29] Lawes T, Lopez-Lozano J-M, Nebot CA et al. Effects of national antibiotic stewardship and infection control strategies on hospital-associated and community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections across a region of Scotland: a non-linear time-series study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15(12):1438–1449. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00315-1

[30] Lawes T, Lopez-Lozano J-M, Nebot CA et al. Turning the tide or riding the waves? Impacts of antibiotic stewardship and infection control on MRSA strain dynamics in a Scottish region over 16 years: non-linear time series analysis. BMJ Open 2015;5(3):e006596. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006596

[31] Micallef C, Aliyu SH, Santos R et al. Introduction of an antifungal stewardship programme targeting high-cost antifungals at a tertiary hospital in Cambridge, England. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(6):1908–1911. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv040

[32] Llewelyn MJ, Hand K, Hopkins S et al. Antibiotic policies in acute English NHS trusts: implementation of ‘Start Smart — Then Focus’ and relationship with Clostridium difficile infection rates. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(4):1230–1235. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku515

[33] Aldeyab MA, McElnay JC, Scott MG et al. A modified method for measuring antibiotic use in healthcare settings: implications for antibiotic stewardship and benchmarking. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69(4):1132–1141. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt458

[34] Schelenz S, Nwaka D & Hunter PR. Longitudinal surveillance of bacteraemia in haematology and oncology patients at a UK cancer centre and the impact of ciprofloxacin use on antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(6):1431–1438. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt002

[35] Berrington A. Antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals: be careful what you measure. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(1):163–168. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp399

[36] Cooke J, Alexander K, Charani E et al. Antimicrobial stewardship: an evidence-based, antimicrobial self-assessment toolkit (ASAT) for acute hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(12):2669–2673. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq367

[37] Bailey C, Tully M & Cooke J. Perspectives of clinical microbiologists on antimicrobial stewardship programmes within NHS trusts in England. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2015;4:47. doi: 10.1186/s13756-015-0090-3

[38] Bailey C, Tully M & Cooke J. An investigation into the content validity of the antimicrobial self-assessment toolkit for NHS Trusts (ASAT v15a) using cognitive interviews with antimicrobial pharmacists. J Clin Pharm Ther 2015;40(2):208–212. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12248

[39] Bailey C, Tully MP, Pampaka M & Cooke J. Rasch analysis of the antimicrobial self-assessment toolkit for National Health Service (NHS) Trusts (ASAT v17). J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(2):604–613. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw434

[40] Good Business, Wellcome Trust. Exploring the consumer perspective on antimicrobial resistance. Wellcome Trust (London), 2015. Available at: https://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b24978000#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0 (accessed June 2018)

[41] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. QuikRead go for C-reactive protein testing in primary care. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib78 (accessed June 2018)

[42] Huddy JR, Ni MZ, Barlow J et al. Point-of-care C-reactive protein for the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infection in NHS primary care: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to adoption. BMJ Open 2016;6(3):e009959. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009959

[43] Ashworth M, White P, Jongsma H et al. Antibiotic prescribing and patient satisfaction in primary care: a cross-sectional analysis of national patient survey data and prescribing data in England. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66(642):e40–e46. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X688105.

[44] Dryden MS, Cooke J & Davey P. Antibiotic stewardship-more education and regulation not more availability? J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;64(5):885–888. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp305

[45] Boyd SE, Moore LSP, Gilchrist M et al. Obtaining antibiotics online from within the UK: a cross-sectional study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(5):1521–1528. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx003

[46] Micallef C, Kildonaviciute K, Castro-Sanchez E et al. Patient and public understanding and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance and stewardship in a UK hospital: should public campaigns change focus? J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(1):311–314. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw387

[47] Harris DJ. Initiatives to improve appropriate antibiotic prescribing in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(11):2424–2427. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt360

[48] Nathwani D & Christie P. The Scottish approach to enhancing antimicrobial stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60(Suppl 1):i69–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm162

[49] Dryden M, Johnson AP, Ashiru-Oredope D & Sharland M. Using antibiotics responsibly: right drug, right time, right dose, right duration. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011;66(11):2441–2443. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr370

[50] Davey P & Garner S, on behalf of the Professional Education Subgroup of Specialist Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance. Professional education on antimicrobial prescribing: a report from the Specialist Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance (SACAR) Professional Education Subgroup. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60(Suppl 1):i27–i32. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm154

[51] Castro-Sanchez E, Drumright LN, Gharbi M et al. Mapping antimicrobial stewardship in undergraduate medical, dental, pharmacy, nursing and veterinary education in the United Kingdom. PLOS One 2016;11(2):e0150056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150056

[52] Rawson TM, Butters TP, Moore LSP et al. Exploring the coverage of antimicrobial stewardship across UK clinical postgraduate training curricula. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71(11):3284–3292. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw280

[53] Ashiru-Oredope D, Cookson B, Fry C et al., on behalf of the Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection Professional Education Subgroup. Developing the first national antimicrobial prescribing and stewardship competences. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69(11):2886–2888. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku350

[54] McNulty CA. European Antibiotic Awareness Day 2012: general practitioners encouraged to TARGET antibiotics through guidance, education and tools. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67(11):2543–2546. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks358

[55] Sneddon J, Gilchrist M & Wickens H. Development of an expert professional curriculum for antimicrobial pharmacists in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(5):1277–1280. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku543

[56] Nathwani D, Guise T & Gilchrist M, on behalf of British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. E-learning for global antimicrobial stewardship. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17(6):579. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30275-X

[57] Finch R & Sharland M. 18 November and beyond: observations on the EU Antibiotic Awareness Day. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63(4):633–635. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp039

[58] McNulty CAM, Cookson BD & Lewis MAO. Education of healthcare professionals and the public. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67(Suppl 1):i11–i18. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks199

[59] Lecky DM & McNulty CAM. Current initiatives to improve prudent antibiotic use amongst school-aged children. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(11):2428–2430. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt361

[60] Hand KS, Cumming D, Hopkins S et al. Electronic prescribing system design priorities for antimicrobial stewardship: a cross-sectional survey of 142 UK infection specialists. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(4):1206–1216. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw524

[61] Johnson AP. Improving antimicrobial stewardship: AmWeb, a tool for helping microbiologists in England to ‘Start Smart’ when advising on antibiotic treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(10):2181–2182. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt216

[62] Charani E, Gharbi M, Moore LSP et al. Effect of adding a mobile health intervention to a multimodal antimicrobial stewardship programme across three teaching hospitals: an interrupted time series study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72(6):1825–1831. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx040

[63] Charani E, Kyratsis Y, Lawson W et al. An analysis of the development and implementation of a smartphone application for the delivery of antimicrobial prescribing policy: lessons learnt. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68(4):960–967. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks492

[64] Micallef C, McLeod M, Castro-Sánchez E et al. An evidence-based antimicrobial stewardship smartphone app for hospital outpatients: survey-based needs assessment among patients. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4(3):e83. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5243