Introduction

In 2019, recognising the threat a global influenza pandemic posed to public health, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched its global influenza strategy, in which it calls for “every country to have a tailored influenza programme that contributes to national and global preparedness and health security”[1]

.

Influenza is a highly contagious viral infection that affects between 3 million and 5 million people globally each year, and is responsible for between 290,000 and 650,000 respiratory deaths over the same period[1]

. For many, influenza is a mild disease; however, for the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions, the outcome can be more serious. As early as 2003, the WHO adopted resolution WHA56.19, which emphasises the need to vaccinate 75% of adults aged 60 years and above, and to increase vaccination coverage for all those in high-risk groups (e.g. patients with diabetes and immunosuppressed patients)[2]

. However, in the 2014/2015 influenza vaccination season, vaccine uptake across Europe for older people was still below the WHO target, with a median uptake of 34% and a range of 0–76% (Scotland being the only country to have achieved the target)[3]

. By 2017, no improvement had been noted, with a vaccination rate of 44% across Europe for people aged 65 years and above — the UK achieved the highest uptake, with 73%[4]

.

Historically, the influenza vaccination was only available from GPs, but following some small-scale, locally commissioned NHS pilots and a larger, region-wide pilot in London in 2015, an NHS-funded national service for all community pharmacies was commissioned, legislated by the community pharmacy seasonal influenza vaccination advanced service direction 7A; part of the National Health Service Act 2006[5],[6],[7]

. Since then, in addition to private services, any community pharmacy in England could deliver this commissioned service, providing it had a private consultation room; could procure the appropriate strains of influenza vaccination for the northern hemisphere for the season; could meet all data-recording obligations; and the pharmacist had completed the identified training requirements, all of which were detailed in the annually revised service specification from NHS England and NHS Improvement[8]

.

Nationally, the service has grown since launch, from 0.6 million doses being administered in 2015/2016, increasing to 1.7 million doses in 2019/2020 across all community pharmacies[9]

. By quantity of vaccinations, the fifth-largest participating pharmacy chain in England is Day Lewis, one of the largest independent pharmacy groups in Europe[10]

. From 1 September 2019 to 31 March 2020, all Day Lewis pharmacies participated in the annual NHS influenza vaccination programme, in addition to offering a private influenza vaccination for those not eligible for the NHS scheme. During this period, 96,183 patients consented to having an influenza vaccine administered by a community pharmacist in a community pharmacy setting[11]

. For 79.8% (n=76,752) of patients, the service was funded by the NHS, while the remaining 20.2% (n=19,431) of patients engaged in the private service[11]

.

While the number of vaccines administered is an important metric for contributing towards delivering the WHO’s ambitions, the quality of the service offered to patients is also paramount. Furthermore, quality improvement to enhance patient experience, through evaluating pharmacy services, is an important part of professional practice. Watson, Silver and Watkins considered service quality in community pharmacy and made recommendations about the quality of care, focusing on three themes: person-centredness, professionalism and privacy, as these were deemed what mattered most to patients from their research[12]

.

For person-centredness, they concluded that “relational aspects with pharmacy personnel” was important; caring and friendly staff were noted as being central to the delivery of a quality service. For professionalism, the participants assessed quality through the appearance of the staff, levels of training attained, competence and confidence in their ability to give advice and, finally, a light, hygienic and clean environment. In terms of privacy, the quality was perceived by the participants to include a confidential room that enabled private consultations[12]

.

Patient satisfaction with community pharmacist-led influenza vaccine services

Research published to date indicates that overall satisfaction with the community pharmacist-led influenza vaccination service appears to be high. For example, one of the first locally commissioned community pharmacy influenza vaccination services was implemented on the Isle of Wight by the primary care trust in 2010; in their analysis of this initiative, Warner et al. concluded that the service helped increase vaccination uptake and was “associated with high levels of patient acceptability”[13]

. The authors noted that proportionately higher levels of carers and frontline healthcare workers were vaccinated than the GP-led service in this locality. In addition, the high level of patient satisfaction was linked with the accessibility of the community pharmacy (with no appointments required), reduced infection risk, ease of access and a perceived reduction in workload for GP practices[13]

. Of the 1,597 respondents, 98% (n =1,540/1,565) stated that they would use the service again in the future and 91% (n =1,427/1,570) assessed the service to be excellent[13]

.

Following an evaluation of the NHS influenza vaccination service in London in 2015, Atkins et al. noted a high level of patient satisfaction with the first large-scale community pharmacy pilot[6]

. Of 11,754 patient respondents, 97.3% (n=11,436) were very satisfied with the service and 99.1% (n=11,645) were happy to have other vaccines administered by the community pharmacist[6]

. In a subsequent study in the West Midlands in 2017, Rai and Wood noted that patient satisfaction was, again, high, with 95.8% (n=8,066) respondents stating that the influenza vaccine administration was as good as that by a nurse or GP[14]

. Furthermore, 99.6% (n=8,156) of patients stated that they would use the service in the future, with key factors including increased patient choice and convenience[14]

.

In a mixed methods research study conducted in Western Australia in 2016, Hattingh et al. noted that “vaccine delivery was safe” and that community pharmacies were both accessible and convenient for service users and, as a result, the service could be extended to other vaccines[15]

. In another Western Australian study in 2018, Burt, Hattingh and Czarniak evaluated patient satisfaction and the experience of an influenza vaccination service in 13 community pharmacies[16]

. Overall, 99.5% (n=432) of patients were satisfied with the service and 97.2% (n=422) agreed that they would return to a community pharmacy for a vaccination in the future. In addition, 60.4% (n=262) of patients stated that they would like pharmacists to administer vaccines for other conditions[16]

.

To profile citizens accessing the pharmacist-led service, Anderson and Thornley surveyed 1,741 patients across 55 pharmacies in England in 2016. They noted that there was access from “all postcode areas, including some from the most deprived localities”[17]

. They concluded that the influenza vaccination service was “highly accessed by patients from all socio-demographic areas”, including frontline healthcare workers, carers and people of working age, because of the accessibility and convenience of community pharmacy[17]

.

In a 2017 review of the influenza vaccination service in England, the United States and Portugal, Kirkdale et al. noted that a community pharmacist-led vaccination service overall increased the number of at-risk patients receiving the vaccination and, furthermore, that the service could “create value for payors and reduce pressure on health systems[18]

. In a second paper in the same journal, Kirkdale et al. described the barriers to implementation of a vaccination service, including differing regulatory frameworks, remuneration mechanisms, training requirements and operating models[19]

. They also noted the varying requirements for facilities, recording of data, patient engagement and interprofessional working[19]

.

In summary, a high similarity in findings has been noted across the various studies, with overall patient satisfaction levels high.

Study background

For this study, a service evaluation was conducted to assess a specific service in a healthcare setting, which sought to “assess how well a service is achieving its intended aims” from the perspective of patient benefit[20]

. This was conducted using the NHS Health Research Authority (HRA) definition: that the single aim of a service evaluation is “to define or judge current care”, and to measure and assess the delivery of the current service, without randomisation or allocation of patients to a particular intervention, with the desired outcome being to inform local decision making and improve the service in the future[21]

. The service evaluation framework used themes on patient perspective highlighted by Watson, Silver and Watkins that focused on quality of pharmacy services in the community setting, person-centeredness, professionalism and privacy[12]

.

Aim

To achieve an improvement of quality in patient care, a service evaluation of the Day Lewis influenza vaccination programme was completed between 1 January 2020 and 29 February 2020. This aimed to evaluate the person-centredness, professionalism and privacy of the service, with the desired outcome to make recommendations for service improvement for the 2020/2021 influenza vaccination season.

Objectives

- To design a survey instrument to evaluate the quality and acceptability of an influenza vaccination service in a community pharmacy setting through attitudinal measurement;

- To implement the survey instrument across 55 community pharmacy settings towards the end of the 2019/2020 influenza vaccination season;

- To evaluate the results from the survey instrument for the attributes of person-centredness, professionalism and privacy;

- To make recommendations based on collected data for service improvement for the 2020/2021 influenza vaccination season.

Ethics approval

As this study was a service evaluation and as all data were anonymised, ethical approval was confirmed to not be required, using the HRA assessment tool[22]

.

Methods

A sample of 19% (n=55) of Day Lewis pharmacies were identified to be included in this study. These pharmacies all hosted a preregistration pharmacist who collected the data as they had a professional knowledge of the service, but had not personally been involved with the administration of the vaccine. Geograhically, these pharmacies were spread across the country, represented the 270 pharmacies within the business, covered a mix of demographic profiles, and were placed in both rural and urban settings. Pharmacies (n=54) were only included in the analysis if they delivered a minimum of 50 vaccinations in the 2019/2020 season — one of the participating pharmacies did not meet this target. It was also anticipated that 500 responses would be achieved, giving a 0.5% sample size.

A survey instrument was designed to meet the objectives of the service evaluation. The survey was divided into two sections: the first section comprised nine closed questions to evaluate the quality and acceptability of a community pharmacy-based influenza vaccination service, and the second section featured demographic data (gender, eligibility category for vaccine and ethnicity). A four-point Likert scale (ranging from ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very unsatisfied’) was used for the attitudinal measurement questions. The survey was then reviewed by a senior academic at the University of Bath and revised prior to printing for circulation to each of the participating pharmacies.

Selection criteria

Preregistration pharmacists in the participating branches were briefed by the researcher in December 2019 and were asked to complete surveys with patients between 1 January 2020 and 29 February 2020. The background to the service evaluation, including a detailed explanation of how to complete the survey, was provided. Each preregistration pharmacist received 20 surveys and was requested to conduct the surveys with select patients. This number of surveys were provided because it meant that there was potential for 1,100 respondents, helping increase the chance that the representative 0.5% would be obtained.

Patients were recruited when they visited the pharmacy. These patients had received the influenza vaccination (either NHS-funded or private) from the pharmacy within the previous four months and would give their consent to participate in the service evaluation. Each patient was then asked to complete the first part of the survey in the confidential setting of the consultation room. The preregistration pharmacist then completed the second part of the survey with the patient, ensuring accurate completion of the patients’ demographic and medical profile; no personal information and no identifying information was collected from the participants. Once all the surveys had been completed, they were returned to the Day Lewis support office for data analysis. Although the flu vaccination service ended on 31 March 2020, very few patients were vaccinated after 31 December 2019; therefore, it was unlikely that individuals would receive their vaccination and then immediately complete the survey.

Survey results were then entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Statistical analysis using frequencies, percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were applied for categorical variables (attitudinal measurements), along with medians, means, standard deviation and ranges for variables measured on a continuous scale (demographics).

Results

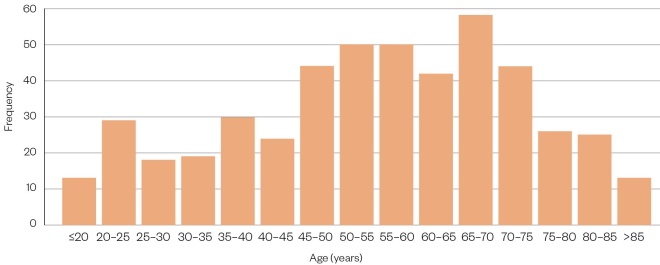

In total, 55 pharmacies in both rural (44%) and urban (56%) settings across England participated in this service evaluation and 54 pharmacies delivered the prerequisite 50 vaccinations to be included in the study. Overall, 45% (n=485) surveys were completed in 57% (n=31) pharmacies and returned for analysis. For the 2019/2020 season, a total of 96,183 vaccines were administered; therefore, a purposive sample of 0.5% (n=481) of total patients vaccinated was achieved. The average age of patients completing the survey was 55.5 years, with a standard deviation of 18.1. The median age was 57 years (range 17–100 years) and there were no statistical outliers. The ages of patients were mildly negatively skewed, with a wider variation in younger patients compared with patients older than the average. In addition, there was a mild negative kurtosis with a flatter distribution compared with a normal distribution (Figure).

Figure: Histogram showing frequency distribution

Analysis of the key demographic features noted that of the 363 patients who completed this section, 50% (n=183) were in the category of aged 65 years and above, and the remainder were in one of the high-risk categories, with the highest prevalence being diagnosed with chronic respiratory disease (11%). In terms of gender and ethnicity, 55% (n=256) of respondents were female and 45% (n=210) were male; 67% (n=313) were from a white British background and 33% (n=154) were from all other ethnic groups combined.

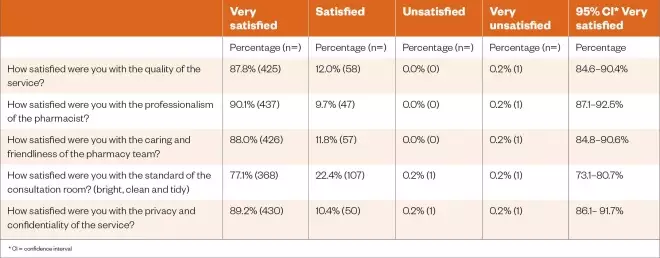

For person-centredness, 87.8% (n=425) of patients were very satisfied (95% CI, 84.6% to 90.4%) with the quality of the influenza vaccination service, and 88.0% (n=426) of patients were very satisfied (95% CI, 88.4% to 90.6%) with the caring and friendliness of the pharmacy team. In relation to professionalism, 90.1% (n=437) of patients were very satisfied (95% CI, 87.1% to 92.5%) with the pharmacist administering the vaccine; however, only 77.1% (n=368) of patients were very satisfied (95% CI, 73.1% to 80.7%) with the standard of the consultation room in terms of brightness, cleanliness and being tidy. For privacy, 89.2% (n=430) of patients were very satisfied (95% CI, 86.1% to 91.7%) with the service (Table 1).

Table 1: Results of survey for person-centredness, professionalism and privacy

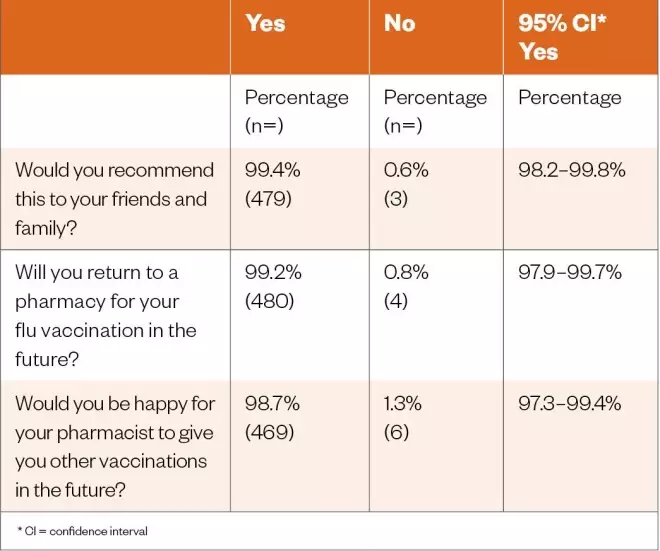

In terms of overall satisfaction, 99.4% (n=479) of patients would recommend the influenza vaccination service to their friends and family (95% CI, 98.2% to 99.8%), 99.2% (n=480) stated that they would return to a community pharmacy for their influenza vaccination in the future (95% CI, 97.9% to 99.7%) and 98.7% (n=469) had confidence in their pharmacist to extend the service to additional vaccinations (95% CI, 97.3% to 99.4%; see Table 2).

Table 2: Results of survey for overall patient satisfaction

Finally, it was noted that 52.1% (n=265) of patients participated in the service because of information or recommendation from the community pharmacy team. This was followed by posters in the window, 18.7% (n=85), and word of mouth, 17.3% (n=88). Advertising was less influential, with only 6.3% (n=32) of patients finding out about the service in this way.

Discussion

While many community pharmacy services may be well established, it is necessary to maintain and improve quality. The “objective measurement of people, practices and organisations against valid and explicit standards” is required to help understand and, subsequently, implement any required change[23]

. This service evaluation has reviewed person-centredness, professionalism and privacy, in line with the literature, to both measure and improve the quality of the service — and with the objective of improving the planning of the influenza vaccination service to be conducted in all Day Lewis pharmacies for the 2020/2021 season.

Person-centredness can be defined as “a standard of care that ensures the patient is at the centre of care delivery”[24]

. Patients value the relationship they have with their local community pharmacy team, with a requirement for a “friendly caring service, continuity of care and the staff ‘knowing’ the individual” [12]

. This is in line with previous studies and was clearly noted in this service evaluation owing to the high levels of patient satisfaction with the quality of the influenza vaccination service, and the caring and friendliness of the pharmacy team. The opportunity to develop this relationship further could be achieved through more proactive recruitment of patients to attend for a vaccine. This may be achieved through personal contact with patients in target groups when they visit the pharmacy, to remind them of the importance of having an influenza vaccination this winter. More direct methods of patient contact may also be deployed; for example, reminder texts or information leaflets included with dispensed medicines, both of which are currently being used in all Day Lewis pharmacies.

Leadership and team-working considerations are important to deliver patient-centred care; the results noted that more than half of the patients were made aware of the service by the pharmacy team. It is therefore essential that the whole pharmacy team are fully appraised and are ambassadors for the benefits of the service. In addition, following a recent government consultation, it has been proposed to allow other healthcare professionals to also administer the influenza vaccine; in community pharmacy, this may open up new opportunities for pharmacy technicians to extend their role[25]

.

Patients clearly expect professionalism in the dispensing of prescriptions, product sales and pharmacy services in a community pharmacy setting. While high levels of satisfaction were noted with the pharmacist administering the vaccine, a lower satisfaction was reported with the standard of the consultation room in terms of brightness, cleanliness and being tidy. There is an opportunity to reflect upon patient expectations, and while community pharmacy consultation rooms may often be smaller in size than a room in a GP surgery or a secondary care setting, the importance of a high-quality clinical environment should not be underestimated. In addition, the consultation room should be in line with the General Pharmaceutical Council’s standards for registered pharmacies[26]

. To achieve this, a full decluttering and cleaning of the room should be considered. This may include removing unnecessary furniture, books and paperwork and replacing fabric-covered patient chairs with easy-to-clean, impermeable, wipeable PVC alternatives to maintain infection control standards[8]

.

In some cases, a more extensive refurbishment may be required. This may include replacing carpet with resilient flooring (vinyl), including coved edging, allowing the flooring to continue up onto the wall for a distance of 150mm for ease of cleaning; introduction of energy-efficient and brighter LED lighting; installation of a clinical hand-wash basin with elbow action or hands-free taps; and a full redecoration. In extreme cases, the pharmacist may decide that a new enlarged and upgraded consultation room may be the best option as a long-term investment; indeed, at Day Lewis, 20 new consultation rooms will be installed by the end of 2020.

In addition, professional clinical leadership of the service will require pharmacists to be fully up to date with the vaccine and service specification and the patient group direction for the community pharmacy flu vaccination service 2020/2021 to ensure full compliance with all legislation surrounding the service[8],[27],[28]

.

Privacy, confidentiality and dignity are all vital elements of a trusting relationship between healthcare professionals and their patients. While a high level of satisfaction was noted, the importance of this to patients in terms of both record keeping and confidential conversations should always be reflected upon for improvement. Patient informed consent in the written form has always proved to be a challenge in terms of storage capacity, but, more recently, environmental reasons to eliminate paper have contributed towards this. New technology to obtain electronic signatures for patient consent should be considered. A thorough review of information governance requirements for each pharmacy, relating to all pharmacy services, could be beneficial.

Confidential discussions can be achieved in the consultation room setting, although it may be a good opportunity to review how soundproof the room is. In addition, consider not placing chairs for patients adjacent to the consultation room. There is a need to ensure lockable filing storage and password-protected computers for all patient-related data.

As an addendum, since the service evaluation commenced, the WHO announced the COVID-19 outbreak to be a global pandemic[29]

. Owing to the pandemic, pharmacy teams will need to be mindful of guidance by public health bodies, such as Public Health England, as to the appropriate requirements for pharmacies, in terms of personal protective equipment and social distancing[30]

. These changes may impact the patient experience of flu vaccination services delivered by community pharmacy.

Examples of measures that could be adopted include:

- Reconfiguring the consultation room to maximise social distancing;

- The introduction of clear perspex acrylic protective screens in the consultation room, either hanging or free-standing;

- Cleaning the consultation room after each vaccination;

- Encouraging patients to complete some of the required consultation questions prior to the appointment;

- Asking patients to wear a short-sleeve garment for ease of vaccination and asking them to wear a face mask or face covering;

- Temperature monitoring of patients prior to vaccination, using an infrared digital handheld thermometer.

Finally, the literature review identified the opportunity to extend the vaccination service to additional vaccines; this was supported by the service evaluation, which showed participants that would be willing to have other vaccines delivered in the community pharmacy. For example, once the COVID-19 vaccine is available, this may be an opportunity for all UK community pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals such as pharmacy technicians, to support the national effort to vaccinate all at-risk groups.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study was that the service evaluation was only conducted in Day Lewis pharmacies and may not be generalised to other community pharmacies in England, or the rest of the UK. In addition, the time since accessing the service to answering the questionnaires could be up to four months, and patients’ detailed memory of events may have deteriorated. Finally, the service evaluation only captured regular patients to the community pharmacy, and not those who visited as a one-off to have the vaccination. In the future, it may be a methodological improvement to conduct the survey with all patients who received the vaccination by also contacting non-regular patients. In addition, a fixed time duration after the vaccination may be more appropriate to survey patients (e.g. four weeks), but not immediately afterwards, to allow for reflection time.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated the importance of person-centredness, professionalism and privacy to the delivery of a quality influenza vaccination service in a community pharmacy setting. It has highlighted how pharmacists and their teams can modify their practices based on the results from this service evaluation to ensure high levels of satisfaction for the 2020/2021 season.

Currently, Day Lewis pharmacists have implemented all the recommendations in this paper, and they have delivered 114% more vaccines up to 1 October 2020, compared with the same period last year. This is testament to the commitment of pharmacists and their teams to step up at a time of national pandemic to protect increased numbers of both older and vulnerable patients from the influenza virus.

Key points

- Influenza is a highly contagious viral infection and severely affects between 3 million and 5 million people globally each year, causing between 290,000 and 650,000 respiratory deaths annually. For most, influenza is a mild disease; however, for the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions, the outcome can be more serious.

- Community pharmacists have been delivering a pharmacy service for the influenza vaccination since 2010 and administered 1.7 million doses as part of the NHS vaccination programme in England in 2019/2020.

- A service evaluation was conducted with 485 patients across 55 pharmacies following the 2019/2020 campaign to assess person-centredness, professionalism and privacy, and to make a recommendation for improvements for the 2020/2021 season.

- Satisfaction levels were high, with 99.4% of patients stating that they would recommend the influenza vaccination service to their friends and family; 99.2% would return to a community pharmacy in the future; and 98.7% had confidence in their pharmacist to extend the service to additional vaccinations.

- Reviewing current practices in community pharmacy will enhance the service in the future; considerations may include proactively recruiting patients, decluttering or refurbishing the consultation room, reviewing patient confidentiality and data security, and implementing any additional measures requred as a result of COVID-19.

About the Author

Tim Rendell is head of pharmacy at Day Lewis, a professional doctorate student at the University of Bath, studying pharmacogenomics, and chair of the operations board at the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education, based at the University of Manchester. Correspondence to: tim.rendell@daylewisplc.co.uk

Financial and conflicts of interest

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

References

[1] World Health Organization. WHO launches new global influenza strategy. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/11-03-2019-who-launches-new-global-influenza-strategy (accessed October 2020)

[2] World Health Organization. Prevention and control of influenza pandemics and annual epidemics. 2003. Available at: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/1_WHA56_19_Prevention_and_control_of_influenza_pandemics.pdf (accessed October 2020)

[3] Jorgensen P, Mereckiene J, Cotter S et al. How close are countries of the WHO European Region to achieving the goal of vaccinating 75% of key risk groups against influenza? Results from national surveys on seasonal influenza vaccination programmes, 2008/2009 to 2014/2015. Vaccine 2018;36(4):442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.019

[4] Eurostat. 44% of elderly people vaccinated against influenza. 2019. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20191209-2 (accessed October 2020)

[5] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. PSNC briefing 007/15: analysis of seasonal influenza vaccination services 2014/15 in England. 2015. Available at: http://psnc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/PSNC-Briefing-007.15-Analysis-of-Seasonal-Influenza-Vaccination-Services-in-England-does-not-include-appendix-on-fees-available-to-all1.pdf (accessed October 2020)

[6] Atkins K, van Hoek AJ, Watson C et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination delivery through community pharmacists in England: evaluation of the London pilot. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009739. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009739

[7] NHS Business Services Authority. The National Health Service Act 2006. The pharmaceutical services (advanced and enhanced services) (England) (amendment) (no. 2) directions 2018. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/2018-08/Drug%20Tariff%20Part%20VIC%20NHS%20PS%20%28Adv%20Enh%20Serv%29%20%28Eng%29%20%28Amnd%29%20%28No2%29%20Dir%202018%2031082018.pdf (accessed October 2020)

[8] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee, NHS England & NHS Improvement. Service specification. Community pharmacy seasonal influenza vaccination advanced service. 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/20-21_Service_specification_for_seasonal_flu_FINAL.pdf (accessed October 2020)

[9] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Flu vaccination data for 2019/20. 2020. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/flu-vaccination-service/flu-vaccination-statistics/flu-vaccination-data-for-2019-20/ (accessed October 2020)

[10] Day Lewis. Our story. 2020. Available at: https://www.daylewis.co.uk/ourstory (accessed October 2020)

[11] Day Lewis. Internal unpublished data. 2020.

[12] Watson MC, Silver K & Watkins R. How does the public conceptualise the quality of care and its measurement in community pharmacies in the UK: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027198. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027198

[13] Warner JG, Portlock J, Smith J & Rutter P. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination uptake using community pharmacies: experience from the Isle of Wight, England. Int J Pharm Prac 2013;21(6):362–367. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12037

[14] Rai GK & Wood A. Effectiveness of community pharmacies in improving seasonal influenza uptake: an evaluation using the Donabedian framework. J Public Health (Oxf) 2017;40(2):359–365. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdx078

[15] Hattingh HL, Sim TF, Parsons R et al. Evaluation of the first pharmacist-administered vaccinations in Western Australia: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011948. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011948

[16] Burt S, Hattingh L & Czarniak P. Evaluation of patient satisfaction and experience towards pharmacist-administered vaccination services in Western Australia.Int J Clin Pharm 2018;40:1519–1527. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0738-1

[17] Anderson C & Thornley T. Who uses pharmacy for flu vaccinations? Population profiling through a UK pharmacy chain. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Care 2016;38:218–222. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0255-z

[18] Kirkdale CL, Nebout G, Megerlin F & Thornley T. Benefits of pharmacist-led flu vaccination services in community pharmacy. Ann Pharm Fr 2017;75(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2016.08.005

[19] Kirkdale CL, Nebout G, Taitel M et al. Implementation of flu vaccination in community pharmacies: understanding the barriers and enablers. Ann Pharm Fr 2017;75(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2016.08.006

[20] Twycross A & Shorten A. Service evaluation, audit and research: what is the difference? Evid Based Nurs 2014;17:65–66. doi: 10.1136/eb-2014-101871

[21] NHS Health Research Authority. Defining research. 2017. Available at: http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/docs/DefiningResearchTable_Oct2017-1.pdf (accessed October 2020)

[22] NHS Health Research Authority. Do I need NHS REC review? 2020. Available at: http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/ (accessed October 2020)

[23] Shaw CD. Measuring against clinical standards. Clinica Chimica Acta 2003;333(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(03)00175-X

[24] McCance T, McCormack B & Dewing J. An exploration of person-centredness in practice. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 2011;16(2):1–10. Available at: https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-16-2011/No2-May-2011/Person-Centredness-in-Practice.aspx (accessed October 2020)

[25] Department of Health and Social Care. Consultation document: changes to Human Medicine Regulations to support the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/distributing-vaccines-and-treatments-for-covid-19-and-flu/consultation-document-changes-to-human-medicine-regulations-to-support-the-rollout-of-covid-19-vaccines#proposed-expansion-to-the-workforce-eligible-to-administer-vaccinations (accessed October 2020)

[26] General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for registered pharmacies. 2018. Available at: https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/standards_for_registered_pharmacies_june_2018_0.pdf (accessed October 2020)

[27] NHS England & NHS Improvement. Implementing the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation advice on vaccines in the NHS annual seasonal flu vaccination programme and reimbursement guidance for 2020/21. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NHS-England-JCVI-advce-and-NHS-reimbursement-flu-vaccine-2020-21.pdf (accessed October 2020)

[28] NHS England. Community pharmacy seasonal influenza vaccine service. 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/community-pharmacy-seasonal-influenza-vaccine-service/ (accessed October 2020)

[29] World Health Organization. R&D blueprint and COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/novel-coronavirus/en/ (accessed October 2020)

[30] Public Health England. COVID-19: guidance for the remobilisation of services within health and care settings Infection prevention and control recommendations. 2020. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/910885/COVID-19_Infection_prevention_and_control_guidance_FINAL_PDF_20082020.pdf (accessed October 2020)