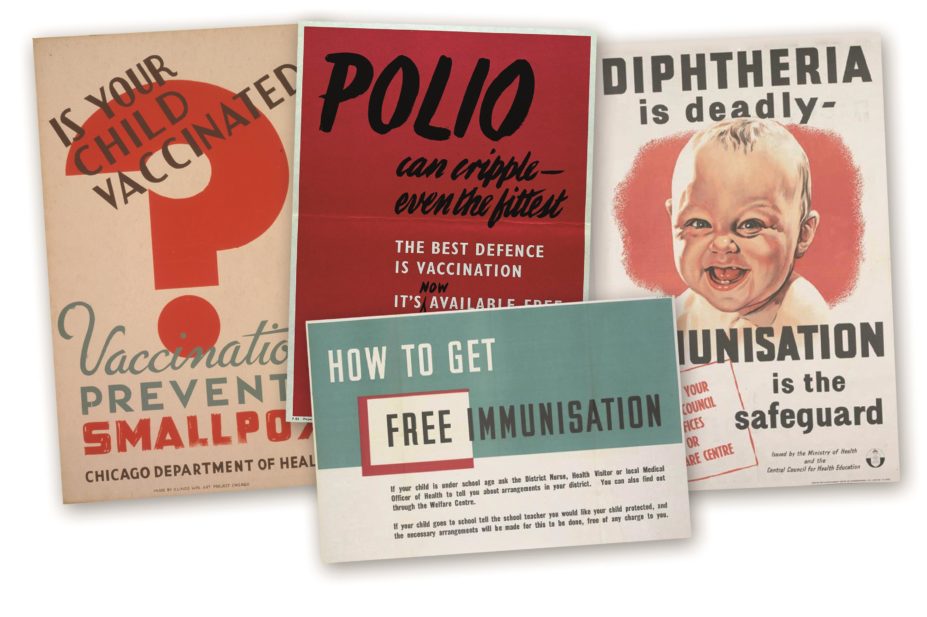

Wikimedia Commons and Wellcome Library, London

Vaccines are possibly the most important modern medical advance and have saved countless lives. They have even led to complete eradication of smallpox infection. In the least developed countries, we cannot get the vaccines to the children who desperately need them; one child dies every 20 seconds from vaccine preventable diseases, according to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Yet in countries where vaccines are readily available, parents sometimes refuse to vaccinate their children. For example, up to 5% of parents in the UK and 9% in the United States refuse to allow their children to be vaccinated with the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

The 2014 measles outbreak in the United States, and the 2015 death of a German toddler from measles during an outbreak in Europe, have once again brought vaccination policies into the worldwide media spotlight. A rich and varied debate has ensued among vaccine advocates, vaccine deniers, politicians and scientists. With little likelihood of consensus in the near future, governments across the world should consider mandatory vaccine policies in their respective countries, or at least implement changes to the current vaccine policies to reduce exemptions, thereby ensuring consistent coverage and stemming further disease outbreaks.

Current vaccination policies

Vaccination policies vary worldwide, from no requirement in Canada to compulsory vaccines for nine childhood diseases in Slovenia[1]

. In the United States, vaccines and well child visits to physicians are covered by insurance or Medicaid and the Vaccines for Children programme, and all 50 states require children to have certain vaccines to attend public school. However, the vaccines that are required vary by state. In the UK, there are no mandates, but routine vaccinations for eight childhood diseases are recommended and provided for free by the NHS. Similar to the United States, most schools in the UK require schoolchildren to receive certain vaccinations. In Slovenia, Italy, Greece, Poland and several other EU countries, some vaccines are mandatory for all children[2]

. Yet each country has a different combination of mandatory vaccines. For example, 13 EU countries require children to receive the polio vaccine, eight countries require the MMR vaccine, and in one country (Latvia) the human papillomavirus vaccine is mandatory. Vaccination is not required in Australia, but instead a tax-free payment is made to parents when a child is vaccinated[1]

.

Even in countries with mandatory vaccine policies, we will never reach 100% coverage. There will always be a small percentage of the population who should not be vaccinated: immunosuppressed patients, cancer patients, people with known allergies to components of the vaccines, and very young children who simply cannot be vaccinated.

The good news is that we do not need to have 100% vaccination rates to protect vulnerable members of society. Maintaining high vaccination rates protects the entire population due to a concept known as community immunity (also known as herd immunity). An example of the effectiveness of high vaccine rates comes from Mississippi, where the vaccination rate exceeds 99% and where they have not had a case of measles since 1992. However, there is a direct correlation between declining vaccine rates and increase in disease incidence[3],[4],[5]

. Parents need to wake up and realise that, if they continue to refuse vaccines, childhood diseases will come back with a vengeance.

Reasons to refuse

Vaccination rates have declined because more and more parents refuse vaccines for their children. Parents want to do what is best for their child and they believe they are making the right choice. However, many parents have been lulled into a state of false complacency. They have not experienced or witnessed polio, measles, or other deadly and debilitating diseases, and they do not take the risk to their children seriously.

The information parents use to justify vaccine refusal is often flawed and unscientific. The internet provides volumes of information, some of which is reliable, much of which is not. Websites with legitimate sounding names disseminate false and distorted information. Vaccine opponents cite fraudulent studies that have been discredited and retracted, such as the infamous study that claimed a link between the MMR vaccine and autism[6]

.

Other opponents say that vaccine side effects are not worth the risk, not realising that complications from natural infection are much more common and serious. With all this misinformation available at the click of a mouse, should we blame parents for being frightened of vaccines?

In the United States, 48 states allow religious exemptions, usually with no requirement to prove association with a particular religion. In addition, 20 states also allow personal belief exemptions with little oversight.

We will never be able to stop infectious diseases from entering our borders. Global transportation can rapidly disseminate disease from one of the estimated 20 million people that contract measles each year. The single best protection we have is to vaccinate as many people as we can to build an immunological border.

Little option

The easiest way to build that immunological border is to tighten up vaccine policies. Mandatory vaccination is certainly a possibility. Despite conjuring up images of children being held down and vaccinated by force, in 1853 England and Wales passed a law mandating vaccination against smallpox. Similarly, Massachusetts in the United States implemented mandatory vaccination against smallpox in 1809. Both policies met with significant resistance. However, in a legal challenge, the US Supreme Court sided with Massachusetts claiming that vaccination was a matter of safety for all citizens.

In countries where freedom and personal liberty are valued above all else, a more subtle approach may be needed; for example, by limiting exemptions to vaccination. In California, all that is required is a signature on a form printed from the internet to obtain a personal belief exemption. These loopholes allow parents to refuse vaccines on unscientific and unproven grounds.

Instead, paediatricians should do more to counsel parents about the safety and efficacy of vaccines, and more education should be provided to school age children. Hopefully, such educational plans can raise vaccine rates without imposing punishments. If parents still refuse vaccination, they should be held accountable. Perhaps they should pay a fine, similar to what Massachusetts instituted in the 1800s smallpox vaccination campaign. At the very least, unvaccinated children must be kept out of school in the event of an outbreak.

Religious exemptions should only be offered to parents who demonstrate membership of a religion that genuinely opposes vaccination, of which there are few. The reality is that many parents use religious exemptions to justify vaccine refusal, even if their religion says nothing about vaccines, or even supports vaccination. Yet, legislators in the United States would likely avoid association with anything viewed as impinging on religious freedom. It is highly likely that religious exemptions will remain, thus governments must do more to strictly enforce their legitimacy.

Keeping the balance

If a country does decide to enact and enforce mandatory vaccination, it will be important to determine which vaccines will be required. Although some vaccines should be mandated on the grounds that the diseases they protect against are highly contagious or extremely debilitating or deadly, the decision is less straightforward for other vaccines. For example, hepatitis B requires direct exposure to blood or open sores and therefore is relatively not contagious for children. Yet if it is contracted, it can cause severe disease. Where should a government draw the line? Should citizens be required to be vaccinated for every disease for which scientists develop a vaccine? Probably not.

Democracies are built on freedom and we should have the freedom to make choices about our healthcare. But we cannot risk making choices that endanger the lives of others. Governments must step in and tighten up rules on vaccination to protect our children and our future.

Cynthia Leifer, PhD, is an associate professor of immunology at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

References

[1] Walkinshaw E. Mandatory vaccinations: the international landscape. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2011;183:1167–1168.

[2] Haverkate M, D’Ancona F, Giambi C et al. Mandatory and recommended vaccination in the EU, Iceland and Norway: results of the VENICE 2010 survey on the ways of implementing national vaccination programmes. Eurosurveillance 2012;17(22).

[3] Majumder M, Cohn EL, Mekaru UR et al. Substandard Vaccination Compliance and the 2015 Measles Outbreak. JAMA Pediatrics 2015. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0384.

[4] van Boven M, Kretzschmar M, Wallinga J et al. Estimation of measles vaccine efficacy and critical vaccination coverage in a highly vaccinated population. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2010;7(52):1537–1544.

[5] van Boven M, Ruijs WLM, Wallinga J et al. Estimation of vaccine efficacy and critical vaccination coverage in partially observed outbreaks. PLOS Computational Biology 2013;9:e1003061.

[6] Retraction — Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. The Lancet 2010;375:445.