Source: Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Gonorrhoea is a sexually-transmitted infection caused by the Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterium. Untreatable antibiotic-resistant strains of the infection are on the increase, the

World Health Organization has recently warned, with some strains showing resistance to all known antibiotics. The problem of dwindling treatment options is further complicated by the fact that there are very few new antibiotics in development.

Before the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, a diverse array of herbs, animals and minerals were used to treat gonorrhoea. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society Museum collection holds many fascinating examples of these pre-antibiotic era treatments. The earliest objects date from the 1600s — before clinical trials and well before the acceptance of the germ theory of infectious disease in the 1880s.

The collection also features numerous examples of antibiotics that were once effective for the condition, but have now become obsolete.

Materia medica of the 1600s

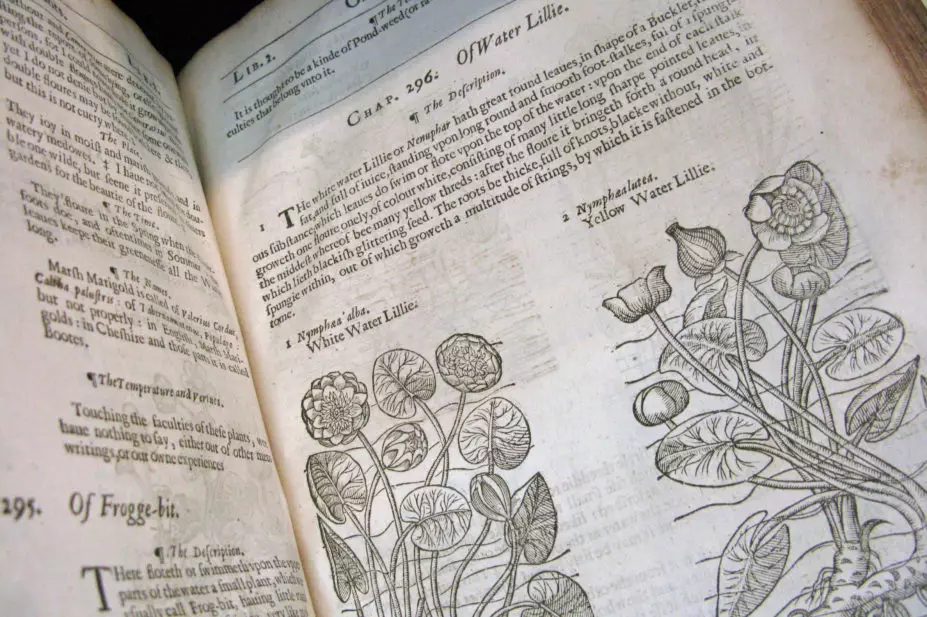

A survey of 17th century herbals — books which describe the botanical features and medical properties of plants — reveals some of the earliest known British treatments for gonorrhoea. A comparison of two popular herbals from the 1600s shows the lack of consensus regarding treatments for gonorrhoea.

The 1633 edition of Gerard’s Herbal recommends six plants, including the water lily: “The green leaves of the great water Lilly either the white or the yellow, laid upon the region of the backe in the small, mightily cease the involuntary flowing of the seed called Gonorrhoea or running of the reins, being two or three times a day removed, and fresh applied thereto.” In John Gerard’s time, gonorrhoea was thought to be an excess of semen — hence the reference to “seed”.

Gerard also believed the juice of knotgrass; comfrey roots; resin from the turpentine fir tree, and the pulp of roasted apples to be beneficial.

In contrast, Nicholas Culpeper’s Complete Herbal, published in 1653, offers a quite different list of treatments: the herb and flowers of Viola tricolor; the white flowering Amaranthus; powdered rupturewort, or the root of Potentilla erecta.

Medicinal ingredients derived from animals and minerals were also used to treat the symptoms of gonorrhoea. Pierre Pomet in his Compleat History of Druggs, first published in England in 1712, stated that powdered coral is “cooling, drying and binding … and is profitable in the Gonorrhoea and Whites”. Pomet also recommended the powdered black tips of the claws of sea crabs.

19th century therapies

During the 1800s, pharmaceutical treatments for gonorrhoea mainly focused on reducing the inflammation and discharge caused by the infection.

Two of the most consistently used drugs were Copaiba balsam and sandalwood oil. Both were either taken internally in capsules, or applied as a solution injected into the urethra. Sandalwood oil, which had been used medicinally since the mid-1400s, was being used as a stimulant and disinfectant of the entire genito-urinary tract by the late 1800s.

In 1879, Albert Neisser discovered the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and proved it to be the causative agent of gonorrhoea. His discovery led to medicines with antiseptic properties being applied locally to the mucous membranes most commonly infected by the gonococcus bacteria — the urethra and the cervix — again to reduce the inflammation and discharge caused by the infection. Frequently used drugs included silver compounds like silver nitrate, colloidal silver and strong silver protein (Protargol), as well as potassium permanganate and zinc sulphate. These drugs were administered as irrigations or injections into the urethra using urethral tubes called bougies, or in pessaries.

An early 20th century treatment regimen

Source: Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Intensive treatment for gonorrhoea in the 20th century required the administration of seven different medicinal preparations over the course of seven days. Numerous solutions of potassium permanganate, Protargol, gold chloride, zinc sulphate, and silver nitrate were applied into the urethra and the bladder using an irrigation tube.

One particular treatment programme recommended in pharmacopoeias during the early 1900s shows how intensive and invasive medicines for gonorrhoea could be. The schedule required the administration of seven different medicinal preparations over the course of seven days. Throughout the week, numerous solutions of potassium permanganate, Protargol, gold chloride, zinc sulphate, and silver nitrate were applied up into the urethra and the bladder using an irrigation tube. During the day, a tablet containing sandalwood oil was to be taken every three hours. Then at night, bougies containing the antiseptic Protargol and the pain reliever Antipyrin were inserted into the urethra. This regimen is a stark contrast to today’s standard treatment of a single antibiotic tablet and a single antibiotic injection.

Development of modern antibiotics for gonorrhoea

Source: Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

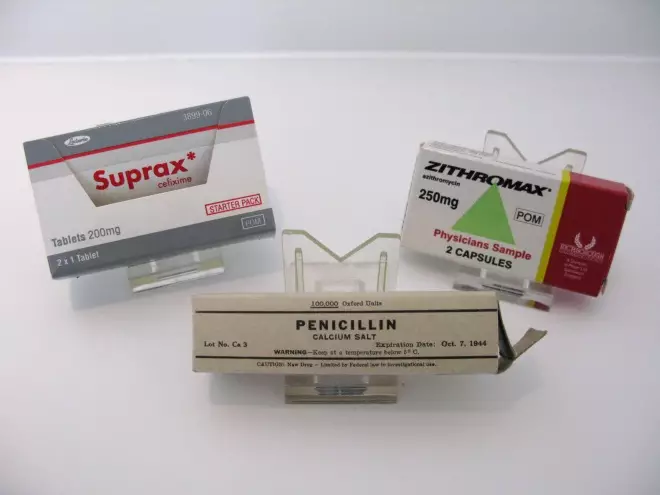

Antibiotics from the early 1940s onwards revolutionised the treatment of gonorrhoea, making it less intensive and more effective compared with previous treatments.

The arrival of antibiotics from the early 1940s onwards revolutionised the treatment of gonorrhoea. Antibiotics were effective, had fewer side effects compared with older drugs, and ended the need for complicated and intensive treatment regimens requiring a number of medicinal preparations in multiple doses.

The initial effectiveness of antibiotics in treating gonorrhoea, compared with the earlier treatments, quickly became apparent. After the introduction of antibiotics, the vast majority of pre-antibiotic treatments were no longer recommended.

However, antibiotics weren’t the wonder drugs they initially appeared to be.

Antibiotic resistance in gonorrhoea

Antibiotic resistance in gonorrhoea is not a recent development. As early as the 1940s, shortly after the first penicillin-based antibiotics were introduced, resistance became apparent as increasingly larger doses were required. During the 1970s, penicillin and tetracycline-resistant strains emerged. By 1986, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that penicillins and tetracyclines only be used in areas of the world where antimicrobial resistance was low.

Over time, more and more antibiotics have had to be abandoned. To protect those that are still effective against the infection, WHO guidelines published in 2016 now recommend single-dose ceftriaxone or cefixime, either on their own or in combination with azithromycin; or spectinomycin as a single dose on its own.

Future treatments for gonorrhoea?

What if gonorrhoea develops resistance to all current antibiotics? Could currently effective antibiotics, like other past therapies, also become museum curiosities? With hardly any new antibiotics in development, scientists are increasingly having to look at other treatment options. While it is unlikely that we will have to resort to pre-antibiotic treatments, it does provide food for thought about what effective treatments will be available in the future.

Aside from new antibiotics, another potential future treatment would be the development of an effective vaccine. During the first half of the 20th century, gonorrhoea vaccines prepared from isolated cultures of the bacterium were administered by injection to increase the patient’s resistance. However, they were abandoned in the 1950s because of doubts about their efficacy, and after the introduction of sulphonamides and penicillin.

New vaccines produced from the bacterium’s surface antigens are being investigated

[1]

, but are still in the experimental stage.

Unfortunately, one of the major hurdles to overcome in the development of an effective vaccine is the ongoing evolution of resistant strains of gonorrhoea. Stewardship of our remaining antibiotic resources is now more urgent than ever.

References

[1] Liu Y, Hammer L, Liu W et al. Experimental vaccine induces Th1-driven immune responses and resistance to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in a murine model. Mucosal Immunology [Online] 2017. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.11

You may also be interested in

Long service of members

Membership fees 2022