Mclean/Shutterstock.com

In 2019, the BMJ published rapid recommendations put together by a guideline panel, which included a “strong recommendation” against the use of thyroid hormones in adults with subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) (see Box)[1].

But the guidelines sparked a row among endocrinologists about the prescribing of levothyroxine for SCH, the merits of which are still being debated.

“It’s very controversial if [SCH] should be treated and there are various opinions about that over the past 10 years,” explains Nicolas Rodondi, director of the Institute of Primary Health Care at the University of Bern in Switzerland, and a member of the guideline panel, which comprised patients, clinicians and methodologists.

It’s very controversial if subclinical hypothyroidism should be treated

Nicolas Rodondi

The panel’s recommendation was based on a meta-analysis of 21 trials, involving 2,192 participants[2]. According to the review, for adults with SCH, thyroid hormones consistently demonstrated “no clinically relevant benefits for quality of life or thyroid-related symptoms”. The panel also considered the burden of taking a pill and attending periodic testing on an ongoing or lifelong basis when making its recommendation.

Instead of prescribing levothyroxine, the guideline says that clinicians should monitor the progression or resolution of thyroid dysfunction in these adults.

However, the recommendation was soon met with backlash from the Society for Endocrinology and the British Thyroid Association, which said the guidance could lead to some patients being deprived of “vital” treatment. “For such a strong recommendation, the evidence supporting this must be compelling. We contend that this is simply not the case,” the organisations said in a joint statement on 29 May 2019.

They said that larger studies, using more sensitive measures, and taking factors such as age and genetics into consideration, were needed before drawing such strong conclusions on the benefits or disadvantages of levothyroxine for the treatment of SCH.

“[Levothyroxine] is a vital treatment in people with overt hypothyroidism and I think all episodes should be treated. I prescribe it every day,” explains Rodondi.

“But if it is a subclinical condition or slightly elevated, I don’t understand why [the Society for Endocrinology and the British Thyroid Association] say it’s a vital treatment — in two-thirds of people [with SCH], when you check six months, one year later, they go back to normal values without treatment.”

The largest randomised controlled trial (RCT) considered in the systematic review, which involved 737 of the 2,192 participants, showed no benefit to prescribing levothyroxine for people with SCH[3].

However, Simon Pearce, a professor of endocrinology at Newcastle University, and programme secretary for the Society for Endocrinology, highlights that the trial was not representative of all patients with SCH.

If you’ve got someone who’s asymptomatic, how are you going to improve their symptoms?

Simon Pearce

“The problem was that the mean age of people in the trial was 74 [years], and the other thing was that they mainly took asymptomatic people and the primary end point was symptoms; if you’ve got someone who’s asymptomatic, how are you going to improve their symptoms?”

“Also, the average dose in the study was 50 microgram, but 75% were on 50 or 25 microgram — those aren’t really the doses of levothyroxine you would think of for full replacement therapy.”

Pearce says that, considering these factors, the recommendations are unlikely to be relevant for people aged under 50 years, particularly if they have symptoms.

“If you’ve got a young person with no symptoms and SCH, you can observe that person with an annual TSH measurement. But if that person has got symptoms, there’s no evidence that they shouldn’t have at least a trial of treatment.”

However, Rodondi, who is one of the authors on the RCT as well as the systematic review, says the limitations of the RCT were taken into account, which is why the panel’s recommendations were based on the wider systematic review, in which the mean age of participants ranged from 32 years to 74 years[2].

The panel’s recommendation does not apply to patients with severe symptoms, young adults aged under 30 years, women who are or trying to become pregnant, or patients with TSH >20mIU/L and normal T4 levels.

Current guidelines

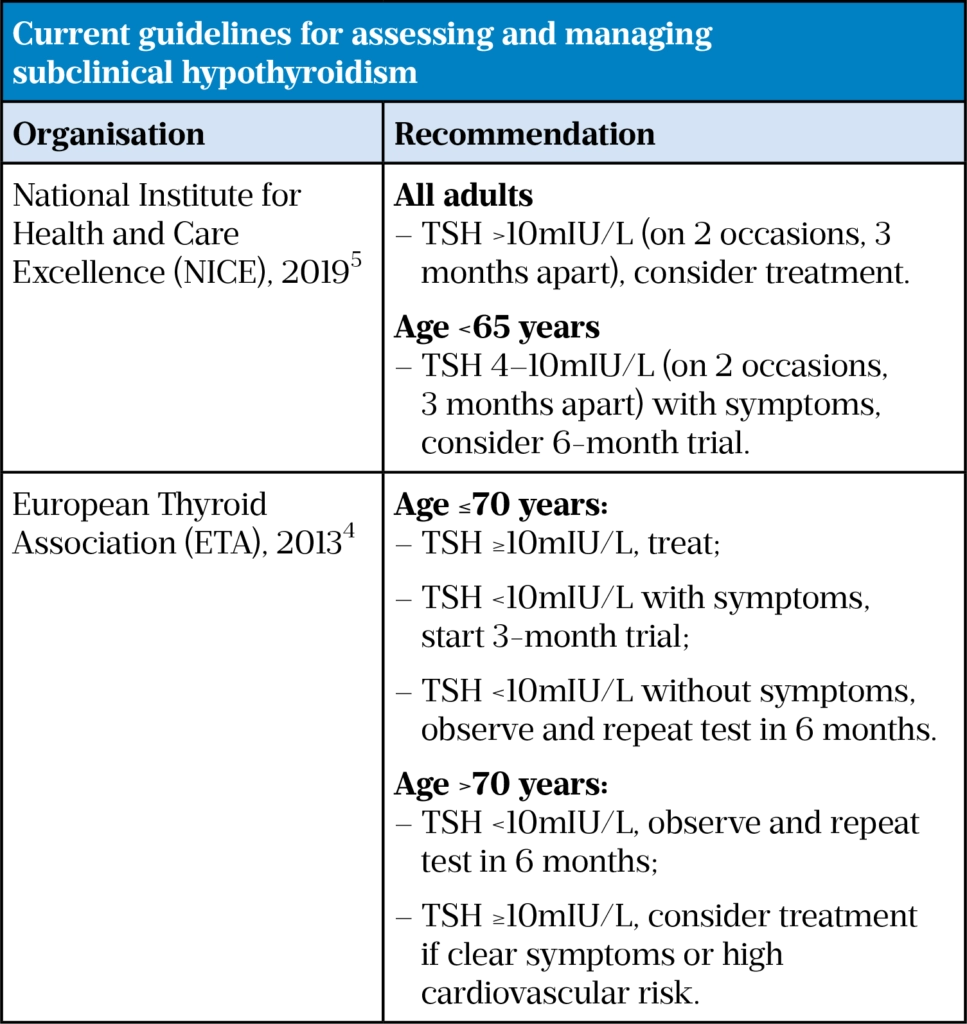

Guidelines generally recommend thyroid hormones for adults with TSH levels of >10mIU/L and for people with lower TSH values who are young, symptomatic, or have specific indications for prescribing.

Pearce was lead author of the 2013 European Thyroid Association guideline on management of SCH[4].

“The guidance is don’t prescribe for older people unless TSH is over 10[mIU/L] — in which case, if they’ve got symptoms, you can consider it,” he explains.

“For young people with SCH that is persistent — in other words, they have TSH that’s over 5 or 6[mIU/L] for 3 or 6 months and they have symptoms that are consistent with hypothyroidism, it’s appropriate to give them a trial of thyroxine therapy for 4–6 months to see if they feel better.

“If they’re seeking pregnancy, it’s obligatory to correct TSH before pregnancy.”

However, it is unclear whether these guidelines, or those published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (see Box 2), are being followed in practice.

“Which guidelines do you follow?” asks Ma’en Al-Mrayat, a consultant endocrinologist at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

Which guidelines do you follow? It is quite a murky business at the moment…

Ma’en Al-Mrayat

“You’ve got the NICE [guideline], you’ve got the European [guidelines] and then, when you refer to your local endocrinologist, you get a slightly different advice. It is quite a murky business at the moment.”

Al-Mrayat believes that the confusion around SCH starts with its basic definition.

“Subclinical is an inaccurate term, because normally you’ll have symptoms and that’s why you do the blood test. And then, hypothyroidism, you’re acknowledging they have an underactive thyroid and therefore you need to do something about it.

“The professional societies need to come in and review it — [we need to] use a terminology that describes it as a biochemical abnormality, rather than a clinical entity.”

As a consultant endocrinologist, Al-Mrayat says he has come across people on both sides of the ‘to treat or not to treat’ argument.

On one hand are those who are keen to correct every abnormality to improve the quality of life of the patient, and on the other hand are those who feel that, by committing to regular blood tests and potentially putting patients on lifelong treatment, they could be doing more harm than good.

Matthew Heppel, an advanced clinical diabetes and endocrinology pharmacist at Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, prefers a personalised approach.

I don’t think you can say for all patients with SCH ‘don’t treat’, because some patients can become quite distressed

Matthew Heppel

“I don’t think you can say for all patients with SCH ‘don’t treat’, because some patients can become quite distressed, especially those who have chronic fatigue.

“There’s a lot more therapy going on there than just correcting the hormone; if you treat it a little bit and it doesn’t resolve, then that helps that person go forward with their health journey to look for other things.

“I do think there are benefits in treating the person rather than treating the disease.”

Increased prescribing

While overt hypothyroidism is found in just 2% of the UK population, the estimated prevalence of SCH is between 4–20%, increasing with age and in women[5]. Increasing levels of levothyroxine prescribing in England over the past decade suggest that it is being relied on as a treatment for SCH.

Prescriptions for levothyroxine have increased exponentially over the past decade.

According to NHS primary care prescribing data, the amount of levothyroxine dispensed in England increased by more than 60% — from 20,426,378 prescriptions in 2008 to 32,956,754 prescriptions in 2019. In fact, prescribing of levothyroxine in 2019 was only surpassed by one other drug, atorvastatin.

Although Heppel says that the rise is likely owing to increased testing over the past decade, research also suggests that clinicians may be feeling the pressure to prescribe.

A large UK retrospective cohort study published in 2014 found that between 2001 and 2009, the annual rate of new levothyroxine prescriptions increased 1.74-fold and the median TSH level at the initiation of levothyroxine therapy fell from 8.7mIU/L to 7.9mIU/L[6].

“And I’m sure it’s much lower now,” adds Pearce.

The study also found that up to 50% of individuals with SCH may be treated inconsistently with the guidelines.

A few people were prescribed levothyroxine when their TSH was normal because they’re tired and the GP couldn’t think of anything better to do with them

Simon Pearce

“It even found that a few people were prescribed levothyroxine when their TSH was normal,” points out Pearce, suggesting this could be “because they’re tired and the GP couldn’t think of anything better to do with them.”

More recently, a Canadian study, published in 2020, found that a minor lowering of the upper limit of the TSH reference range (from 6mIU/L to 4mIU/L) resulted in 500 new, and potentially unnecessary, levothyroxine prescriptions per month and a substantial increase in laboratory test use — around 3,000 to 5,000 tests per month[7].

It concluded that efforts to improve both clinicians’ and patients’ knowledge about SCH were warranted.

“I think that we, as professionals, perceive that our patients want ‘something’ from us, when a lot of the time they just want answers,” says Heppel.

“For some patients, it might be enough to say it’s not exactly the way we would want it to be, but you’re not at a stage where you need any treatment.”

Further compounding the issue is that SCH is linked to very common symptoms, such as fatigue, weight gain or feeling low, that could have many other causes, physical and mental.

“There are so many possible symptoms that could be linked to SCH,” explains Rodondi. “And, for a lot of these conditions we have no other medicines; it’s easier to prescribe pills than to make a weight loss management programme.”

It’s easier to prescribe pills than to make a weight loss management programme

Nicolas Rodondi

Pearce says that it has become more socially acceptable to have a hormone problem than to have what could be a mental health problem.

“It’s also easier for the GP to say, I’ll prescribe some levothyroxine, you might feel better, than to say, you’ve got a mental health problem, I’m going to refer you to CBT [cognitive behavioural therapy] and there’s a nine-month waiting list for CBT.”

At a cost of just £2 per item, levothyroxine is also a very cheap option.

Managing expectations

But once a patient starts taking a medicine, it can be difficult to persuade them to stop.

“Patients feel that the treatment is being withdrawn, which is difficult,” says Al-Mrayat.

“If I was going to prescribe it, I personally would say, this is a trial therapy; let’s give you treatment for three to six months, and then see what happens to your symptoms.”

“[Then] if they come to me six months down the line and say ‘I don’t feel any different’, I can take them off the medication, [and] because we had a plan at the beginning, it doesn’t come as a shock.”

As well as taking a trial approach, it is clear that all patients with SCH cannot be lumped together.

“We use the same reference range for somebody in their 20s as somebody in their 80s,” Al-Mrayat points out.

“[But, there may be] an adaptive advantage of the decline in thyroid function with age — a protective mechanism [or] an adaptive process, and we might be interfering with that.”

A study published in May 2020 found that thyroid hormone replacement among older adults (average age 78 years), even when treated to target, was associated with a significantly increased mortality risk compared with euthyroid individuals with no history of thyroid hormone exposure[8].

The authors of the study said this suggests treating isolated elevated TSH, when changes are owing to ageing adaptations rather than primary thyroid disease, could adversely affect health by altering key homeostatic adaptation.

In addition, recent research presented at the Endocrine Society’s 2021 meeting (20–23 March 2021), has shown that potentially a third of older adults on thyroid hormone are taking medicines that have been known to interfere with thyroid function tests, such as prednisolone and carbamazepine.

The European and NICE guidelines both split approaches to SCH treatment into those below the age of 70 years (treat) and those above (watch and wait), but neither specifically mention younger adults, such as those aged 30 years and below, and the evidence for this age group is limited.

Left untreated, SCH could result in the development of overt hypothyroidism, and observational data suggest that it is also associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality, particularly in those with TSH levels >10 mIU/L[1].

But overtreatment with levothyroxine brings its own downsides: “The harms of unnecessary levothyroxine are atrial fibrillation and osteoporosis, so they’re not insubstantial over a long time,” says Pearce.

The 2019 BMJ Rapid Recommendations highlighted that future research could explore whether there is more benefit of levothyroxine treatment in groups of people for whom there is “less direct evidence and therefore more uncertainty”, including young people aged 30 years and below.

We don’t all wear the same size of clothes so why would we treat everyone with a condition the same?

Matthew Heppel

And, as yet, this is an evidence gap that has not been filled. In the meantime, it is clear that to ensure optimum management, patients with SCH need to be reviewed carefully, regularly and on an individual basis.

“We don’t all wear the same size of clothes, do we, so why would we treat everyone with a condition the same?” says Heppel.

“Thyroid disorders are categorised as an easy thing to manage — you just give them a bit of levothyroxine — but actually it’s much more complicated than that and it requires much more thought … and it’s certainly something that people should think about more.”

- 1Bekkering GE, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, et al. Thyroid hormones treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2019;:l2006. doi:10.1136/bmj.l2006

- 2Feller M, Snel M, Moutzouri E, et al. Association of Thyroid Hormone Therapy With Quality of Life and Thyroid-Related Symptoms in Patients With Subclinical Hypothyroidism. JAMA 2018;320:1349. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.13770

- 3Stott DJ, Rodondi N, Kearney PM, et al. Thyroid Hormone Therapy for Older Adults with Subclinical Hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2534–44. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1603825

- 4Pearce SHS, Brabant G, Duntas LH, et al. 2013 ETA Guideline: Management of Subclinical Hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2013;2:215–28. doi:10.1159/000356507

- 5Thyroid disease: assessment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng145/resources/thyroid-disease-assessment-and-management-pdf-66141781496773 (accessed Apr 2021).

- 6Taylor PN, Iqbal A, Minassian C, et al. Falling Threshold for Treatment of Borderline Elevated Thyrotropin Levels—Balancing Benefits and Risks. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:32. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11312

- 7Symonds C, Kline G, Gjata I, et al. Levothyroxine prescribing and laboratory test use after a minor change in reference range for thyroid-stimulating hormone. CMAJ 2020;192:E469–75. doi:10.1503/cmaj.191663

- 8Abbey EJ, Simonsick EM, McGready J, et al. OR18-05 Thyroid Hormone Use and Survival among Older Adults – Longitudinal Analysis of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). Journal of the Endocrine Society 2020;4. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvaa046.235