JL / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Government figures show that over a one-year period around 1 in 11 adults (aged 16–59 years) used an illicit drug in England and Wales. This equates to around 3 million people. For young people (aged 16–24 years), this proportion more than doubles to around one in five. And, despite huge efforts to reduce illicit drug use, there has been little change in these figures over the past decade.

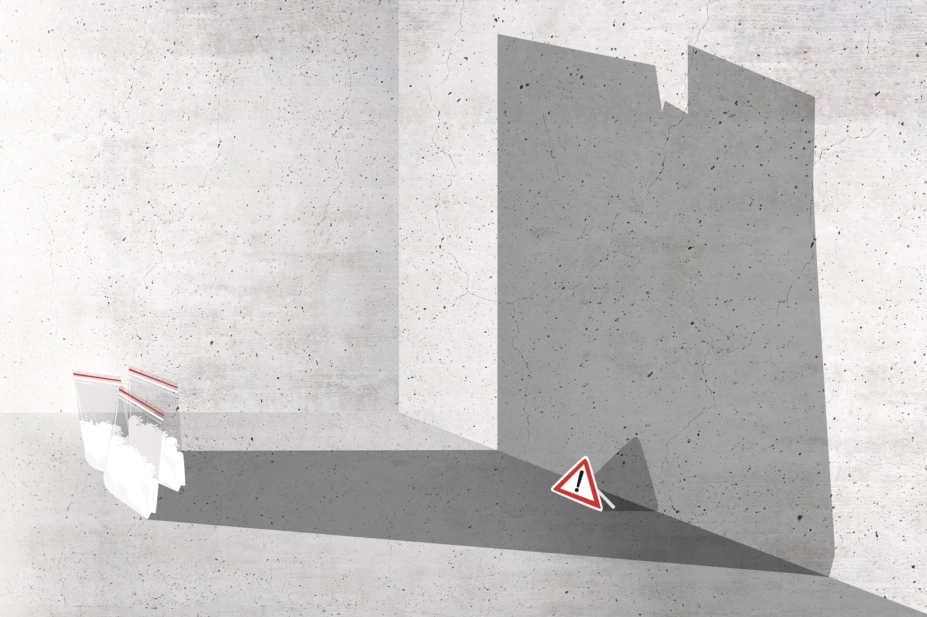

This failure to tackle the problem has consequences. The most recent statistics show that there were 3,756 deaths from drug poisoning in England and Wales in 2017, with two-thirds of these related to misuse of illicit drugs. Pushing illicit substances to the margins is clearly not working and so a new approach is needed.

If people are not going to stop taking these substances, then one way to reduce the level of harm they can cause is to provide users with information on what they may be taking

A new pharmacist-led street drug-testing service in Somerset, south-west England — the first to be licensed by the Home Office — may provide a different way forward.

If people are not going to stop taking these substances, one way to reduce the level of harm they can cause is to provide users with information on what they may be taking. This outreach service, which recently reached the end of its month-long trial, tested samples of illicit substances in real time, offering users advice on the drugs they held, and, where appropriate, brief clinical interventions.

The pilot scheme was operated by the charity Addaction, along with the University of Hertfordshire and The Loop, a non-profit drug testing organisation. The full results of the testing period are yet to be published, but the pharmacists behind it are satisfied that their ‘proof-of-concept’ operation has been a success.

The team told The Pharmaceutical Journal that, despite its short run time, the pilot project analysed a wider-than-expected variety of drugs, brought in across a diverse demographic and saw people with different types of substance misuse histories and drug-taking habits. Some of the drug users were already known to the local drug service, but they also saw recreational drug users who may otherwise not have come into contact with any kind of drug treatment facility.

Some people who used the service said they had changed their drug-taking habits as a result. Others said the brief interventions delivered by staff may have had more of an impact because of the immediate knowledge of what they were intending to take.

Acceptance of the scheme, both by illicit drug users and the general public, was helped by the prominent involvement of pharmacists. This provided a level of trust, those involved say, and also improved the service’s accessibility.

This is only a small pilot, housed in a relatively little-used drug service, so its benefits should not be overstated and the evidence must be published before hard decisions can be made. But those running this service say there has been keen interest in their work within the UK and internationally, and the potential gains could be great if it was replicated in larger towns or cities.

However, local authorities are already having to slash their substance abuse provision as a result of cuts to public health funding — the think tank The Health Foundation estimates there has been a reduction of £900m in funding, in real terms, for public health between 2014/2015 and 2019/2020 in England. This is only made worse by the soaring cost of buprenorphine, which led to local authorities and charities spending £5.5bn on its inflated price concession in 2018. As a result, finding the money to provide such a novel service elsewhere may be a struggle.

Momentum for pharmacists to be given greater scope to employ their clinical skills is building, following the publication of the ‘NHS Long Term Plan’ in January 2019 in England and other intiatives in the devolved nations. The placement of pharmacists in GP surgeries, A&E departments and care homes across the UK and pharmacy negotiators’ hopes of securing a landmark community pharmacy contract in England to reward case management of patients shows what a difference pharmacists can make.

But this pilot potentially shows that pharmacists could have a powerful role in improving public health, using their expert knowledge to reduce harm for drug users and lessening the burden on the NHS. It must be hoped that, somehow, the money can be found to take such an innovative, progressive and valuable pharmacist-led service forward and tackle this intractable problem.