Science Photo Library

Newly qualified pharmacists may find this hard to believe but there was a time, not so long ago, when mobile phones were used for calling people and playing games that involved a 2D snake, films were watched on a VHS player, and we treated almost all patients with a venous thromboembolism (VTE) with warfarin.

As it is a drug that requires regular monitoring and considerable patient education, warfarin presented an opportunity for us, as pharmacists, to start developing pharmacy clinics.

In 2013, a pharmacist colleague and I were approached by the clinical director for the ambulatory care unit with a problem — patients were diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis and started on warfarin, but no one was officially responsible for treatment initiation. We saw an opportunity and agreed to take on the role at Singleton Hospital in Swansea, Wales.

A pharmacist loading warfarin may not be groundbreaking now, with pharmacists running anticoagulant clinics all over the UK, but at the time it was a foot in the door to a more clinical role.

Initially, it wasn’t clear where that door led. When direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) began to be prescribed for VTE following changes in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance in 2014 (which previously called for warfarin to be used as a first-line treatment), our role became almost redundant. Monitoring, counselling and loading were all things that were suddenly far quicker and easier for patients on DOACs.

However, after my colleague left for another job in 2015, I became the sole lead for the VTE clinic and I started to dedicate far more of my time to it, including gaining my independent prescriber qualification in 2018.

A clinician with a specialist interest in venous thromboembolism is needed to improve consistency of management decisions — there is no reason why that clinician can’t be a pharmacist

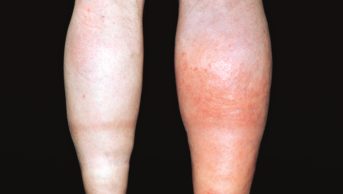

I began to take a considerable interest in the condition, and I slowly came to three realisations. First, VTE management is far more complex than it had appeared. DOACs aren’t a ‘one size fits all’ therapy — the treatment still needs to be individualised. Decisions around treatment duration are complex and require both good consultation skills and a very good understanding of VTE. Also, patients themselves can also sometimes be complex; they bleed and can develop long-term conditions, such as post-thrombotic syndrome.

Second, the condition is almost exclusively managed using medication. And third, both of these facts meant that a clinician with a specialist interest in the condition is needed to improve consistency of management decisions. I felt that there was no reason why that clinician couldn’t be a pharmacist and, importantly, all my medical colleagues completely agreed with me.

And so, with a team of three fellow independent prescriber pharmacists, in late 2018 we set about changing the clinic model so that we would see a patient on the same day that they had been confirmed to have a VTE to decide on an appropriate anticoagulant regime. The previous model meant that patients would be seen up to three days later. From this point, we would be the primary clinicians managing the patient and would review all aspects of the patient’s care, including deciding on the duration of therapy, arranging follow-up investigations and referring to consultant colleagues in patients with certain complications.

We also implemented a dedicated cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT) pathway. In 2015, a study was published that highlighted the lack of support this patient group felt they were receiving after a CAT diagnosis. Our local service evaluation included a knowledge retention study about treatment practices, length of treatment and side effects. The average correct score for patients in our model was 80.6%, compared with 60.2% for the previous model. Simple anxiety scores showed that patients reduced their anxiety levels from 5.2/10 pre-clinic to 1.8/10 after our clinic review.

The service is now the established primary VTE clinic for Swansea Bay University Health Board, with each patient with a VTE in the health board seen as part of our service. We’ll likely see around 500 patients in 2021, having seen just 150 patients in 2017. The service has become a slight victim of its own success as word spread, with similar clinics running in other parts of Wales.

I would argue that VTE is now seen as a pharmacy-managed condition in our health board. I get requests for advice on a daily basis from a variety of healthcare professionals. I also undertake a weekly clinic on behalf of our consultant haematologists, reviewing patients with complex anticoagulant and VTE management issues.

It’s a challenging role, but very rewarding. We were privileged, as a team, to win awards at the Welsh Pharmacy Awards, the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists Awards, and have our work recognised at the Anticoagulant Achievement Awards.

What’s next? We recently received short-term funding for a successful pilot that had us take on a diagnostic role, in which patients were referred to our clinic for VTE diagnosis and then treated by us. It felt like a further organic development for our service. We await news on whether we will gain long-term funding for this but, regardless, it feels like we’ve already come a long way from our humble beginnings.

Kieron Power is clinical lead pharmacist — thrombosis and anticoagulation at Singleton Hospital in Swansea Bay University Health Board

READ MORE: A quiet revolution: how pharmacist prescribers are reshaping parts of the NHS