Shutterstock.com

Pharmacists have had the opportunity to become independent prescribers for 15 years, but it is only in the past few years that their contribution to the health service has taken off.

When it was announced in 2006, this extension of prescribing powers was hailed by Keith Ridge, chief pharmaceutical officer for England, as “the dawn of a new era” that will “transform the public’s perception of pharmacy and the services they deliver”.

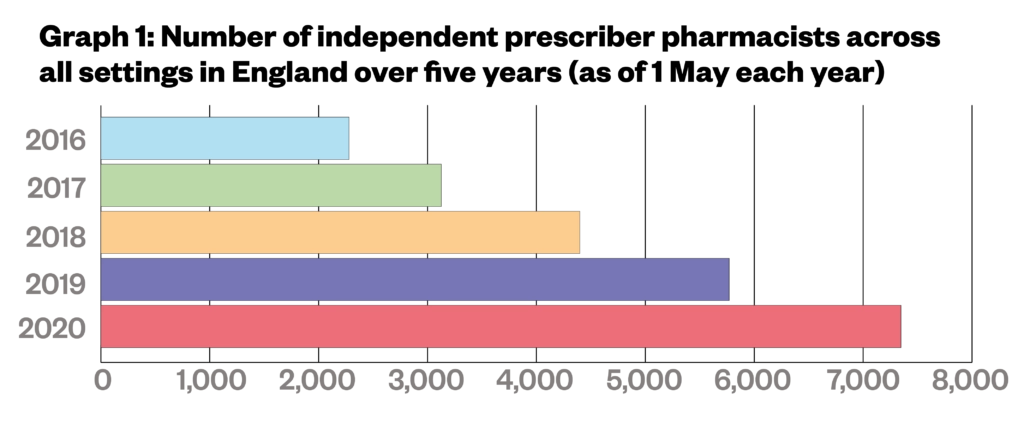

However, this transformation has been slow moving. A decade later, in 2016, there were only 2,200 pharmacist independent prescribers in England.

This has increased markedly in the subsequent years (see Graph 1), but a survey of just over 12,300 pharmacists across England, Scotland and Wales conducted by the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) in 2019 suggested that of the 16% who had an independent prescribing qualification, 20% had never used it. The majority (57%) said this was because they had not been given the opportunity to do so.

Source: Freedom of Information data from the General Pharmaceutical Council

Pharmacist independent prescribing in hospitals has been particularly slow to embed. Despite the recommendation from Lord Carter’s 2016 report, ‘Operational productivity and performance in English NHS acute hospitals: unwarranted variations‘, that 50% of hospital pharmacists should be actively prescribing by 2020, data compiled by the NHS Benchmarking Network — seen by The Pharmaceutical Journal — show that just 32% of hospital pharmacists were qualified as independent prescribers in 2020. And this is only a 6 percentage point increase on the number of hospital pharmacist prescribers in 2017 at 26%.

The NHS Benchmarking Network data show that of those hospital pharmacists that are qualified to prescribe, only 60% routinely do so. But the tide may be turning — at least for some pharmacists.

A growing trend

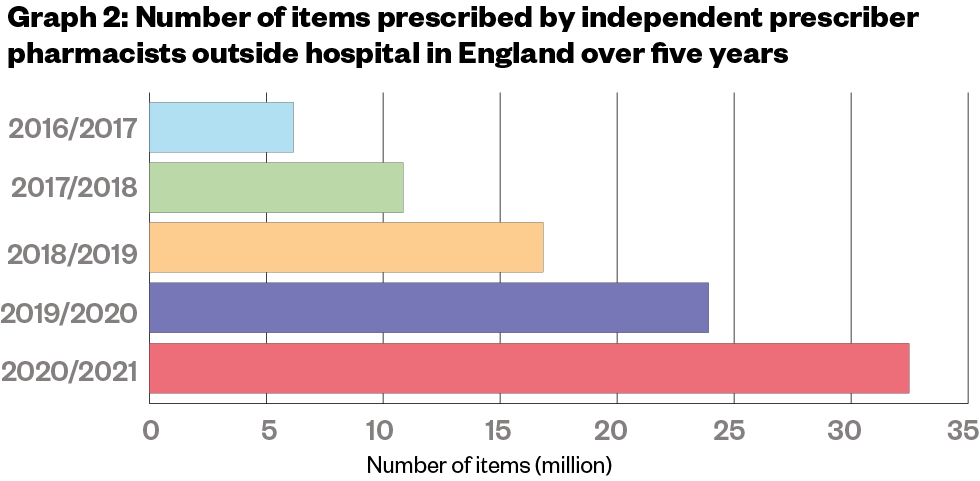

Data, obtained by The Pharmaceutical Journal through a freedom of information (FOI) request made on 20 May 2021 to the GPhC and NHS Business Services Authority, show that independent prescribing pharmacists working outside hospitals in England prescribed 32.5 million items in 2020 (see Graph 2).

Freedom of Information data from the NHS Business Services Authority

This is five times as many items as were prescribed in 2015 (6.2 million items) and coincides with a more than three-fold increase in the number of pharmacist independent prescribers working across all settings in the country from 2,224 in 2016 to 7,348 in 2020.

These figures perhaps show a growing confidence in the profession to prescribe, and also that pharmacist independent prescribers are being given even more opportunities to do so.

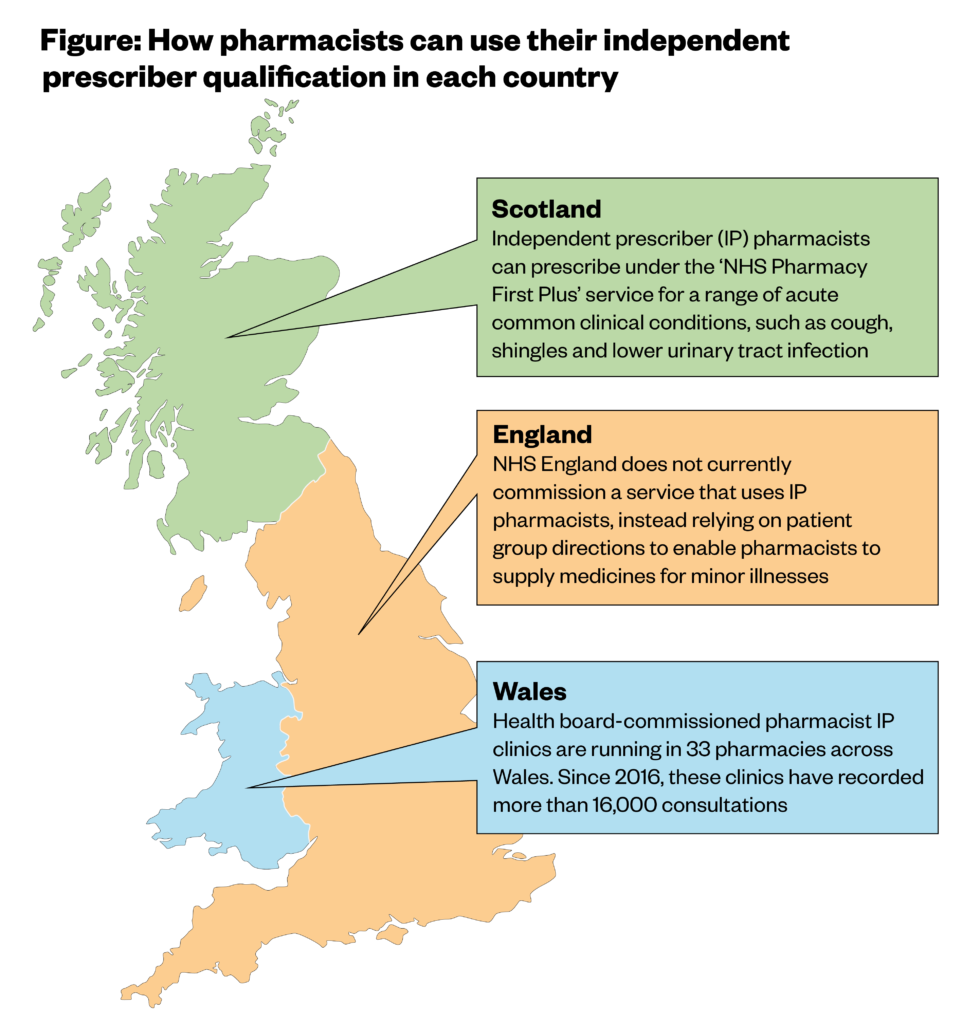

In Wales, the number of clinics run by community pharmacist independent prescribers is starting to increase since their launch 2016, with data from June 2021 showing that the 33 pharmacies offering prescribing services in the country have carried out more than 16,000 consultations in the past five years.

Meanwhile, community pharmacist independent prescribers in Scotland have been able to receive funding to treat acute common clinical conditions — such as cough, shingles and lower urinary tract infections — through the NHS Pharmacy First Plus service since September 2020.

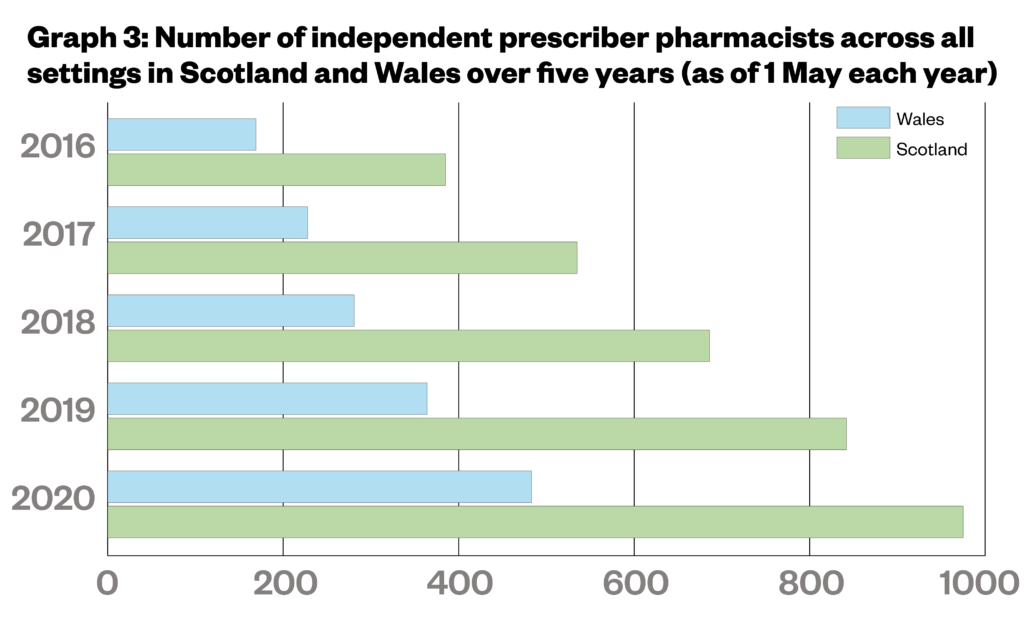

According to data obtained through a FOI request from the GPhC, both countries have seen an increase in the number of pharmacist independent prescribers since 2016 (see Graph 3). The numbers increased from 167 in 2016 to 483 in 2020 in Wales; and from 390 in 2016 to 975 in 2020 in Scotland.

Freedom of Information data from the General Pharmaceutical Council

One sector that has seen very little progress so far is community pharmacy in England, where there is very little opportunity for prescribers to use their qualification.

David Evans, chief pharmacist and managing director at Daleacre Healthcare, who owns 12 Evans Pharmacy branches across Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, says working in a GP practice is “the only chance you get to use your independent prescribing qualification at the moment”.

Evans has been an independent prescriber for 14 years but says he has never been commissioned by the NHS to use his qualification. He says he went into independent prescribing to provide travel medicine and lifestyle medication — such as athlete’s foot cream — privately.

“There are a number of services that could be done quite easily by an independent prescriber in a community pharmacy,” he says.

Some pharmacies in Derbyshire, including those run by Evans, provide the Community Pharmacy Extended Care Services, which enable pharmacists in the NHS England Midlands region to supply prescription-only medicines for urinary tract infections, impetigo, infected insect bites and infected eczema.

However, this scheme relies on pharmacists signing patient group directions (PGDs) rather than using an independent prescriber qualification.

“Nobody has thought to say, ‘Well, actually, we don’t need PGDs — these guys have a prescribing qualification. Why don’t we use that?’,” he says.

Technology barrier

In Great Britain, NHS England is the only commissioning body not offering a national service in which pharmacist can use their independent prescribing powers (see Figure).

For pharmacist prescribers in England, using a prescribing qualification in the community setting is a “trickier area … because the systems don’t talk to each other yet”, says Hannah Syed, diabetes lead pharmacist at East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, who is also a GP practice pharmacist and community pharmacy locum.

“Getting hospital systems to talk to primary care systems is challenging enough,” she explains.

“The technology is there, but for pharmacists in the community to be able to take on patients and prescribe appropriately, they’re going to need access to more patient records and blood tests, which at the moment, there’s just not the facility for them to have.”

Pharmacist access to patient records was one of eight recommendations made by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) in April 2021 as part of its campaign for the greater use of pharmacist independent prescribers.

The recommendations followed the approval of new GPhC initial education and training standards for pharmacists on 11 December 2020, which say that newly qualified pharmacists will be able to become prescribers at the point of registration by 2025/2026.

In its recommendations, the RPS warned that these changes to education standards make it “essential that systems are in place to support pharmacist independent prescribers to use [their] skills and get the most from this investment”.

However, the document also says that the existing workforce “must not be left behind” and instead ensure “adequate resources” are available for registered pharmacists to undertake training and qualify as independent prescribers.

“Current challenges to starting the training include funding of courses, finding cover whilst training and finding a suitable superviser,” it says.

Training opportunities

Training is another area where England lags behind the devolved nations. In 2021/2022, the Welsh government is increasing the number of subsidised independent prescriber training places from 50 to 60 in 2021/2022, plus offering a £3,000 training bursary.

Scottish community pharmacists have also been able to access fully-funded independent prescriber training since January 2019, when NHS Education for Scotland covered the cost of 25 places for community pharmacists at the University of Strathclyde.

Community pharmacists in England, meanwhile, have so far only received unfulfilled promises.

In May 2021, Ridge told attendees of the NHS Confederation Conference that NHS England was “identifying funding” to provide community pharmacists with independent prescriber training.

At the time of writing, The Pharmaceutical Journal understands that further details of the funding will be announced shortly.

NHS England now has less than five years to shape community pharmacy into a profession suitable for a prescriber or risk leaving many newly registered pharmacist prescribers without a way of keeping up their skills.

It may, as Evans says, take a “fundamental shift” in NHS England, but “a lot might change in five years’ time”.