Shutterstock.com and Alamy Stock Photo

It has been an unsettling 12 months for pharmacy and, as 2017 draws to a close, there are still a number of unresolved issues hanging over the New Year.

Brexit prompted the decision by the drugs safety watchdog, the European Medicines Agency, to move its HQ from London. In November it announced it will make Amsterdam its new European home. But the impact of that move on London and the UK remains unknown.

Brexit also brought uncertainty to the life sciences sector this year. There is continuing concern about future funding for research and development and there is still a question mark over whether the UK will remain an attractive destination for scientists in the run-up to, and after it is outside of, the European Union.

The surprise general election in June also created additional pressures for pharmacy organisations. While Jeremy Hunt kept his job as health secretary in the post-election cabinet, pharmacy minister David Mowat — who had held the post for just one year — lost his Warrington South seat.

So half way through 2017, and just as cuts to community pharmacy really started to bite and the NHS financial crisis deepened, pharmacy leaders were forced to forge a new relationship with his successor Stephen Brine.

Brine, who was appointed in July, has already declared himself to be a friend of pharmacy. But whether the minister can be its champion in 2018 as it tackles continuing cuts and the fallout of Brexit, only the next 12 months will tell.

We look back at some of the main issues to have impacted pharmacy during 2017:

- Decriminalisation of inadvertent dispensing errors

- Supervision

- Revalidation

- Primary care integration

- Low-value medicines

- AMR

Decriminalisation of inadvertent dispensing errors

Source: Shutterstock.com

At the end of 2016, community pharmacist Martin White from Northern Ireland began a suspended prison sentence after pleading guilty to inadvertently dispensing the wrong drug to a patient who later died.

He became the latest pharmacist to find himself facing a criminal prosecution for making a dispensing mistake — attributing his fatal error to similar packet branding on two different medicines sitting side by side on the same shelf.

But as 2017 ends, the necessary Order to prevent cases such as White’s, resulting in a criminal prosecution, was finally laid before parliament in Westminster — following a year dogged by delays.

In January, the then health minister David Mowat promised that the legislative change needed, which will remove the threat of criminal prosecution from community pharmacists and technicians working in registered pharmacies, was poised to be placed before parliament. At the same time Ken Jarrold, chair of the Rebalancing Medicines Legislation and Pharmacy Regulation Programme Board, which was set up by the government to push through the legislation, confessed to delays, and seeking to reassure the profession said: “That [the delay] does not mean that it is unimportant or that we will abandon our task …The case of Martin White is evidence that our work is relevant.”

Three months on (April), the decision by Prime Minister Theresa May to call a surprise general election brought another postponement which Jarrold described as “very frustrating.”

But by the end of the summer there were indications that things were starting to move again when the new pharmacy minister Stephen Brine told the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) annual conference in September that it was his personal priority to ensure that the law would be changed.

And in October, the Board promised that the vital statutory Order would be in place before Christmas. That pledge was finally fulfilled in November, prompting Paul Bennett, RPS chief executive, to declare: “This … marks the beginning of the end for the automatic criminalisation of inadvertent dispensing errors.”

Finally, the Pharmacy (Preparation and Dispensing Errors – Registered Pharmacies) Order 2018 was presented by pharmacy minister, Steve Brine, to the First Delegated Legislation Committee on Monday 4 December.

Brine described the order as an important step forward in addressing barriers to pharmacists providing a safe, higher quality service.

“This Order supports improved patient safety by encouraging a culture of candid and fulsome contributions from those involved when things go wrong,” he said, adding that working under such a threat of sanction has been a hindrance to the reporting of errors and accidents and therefore wider learning.

“Let me be clear — this is not about accepting the inevitability of dispensing errors … it is to ensure we collect info on errors that do occur and think hard about how to prevent them in future,” said Brine.

In December the legislation was passed by committees in both the House of Lords and the House of Commons.The next step is for the motion to be put before both Houses of Parliament for approval before progressing to the Privy Council where it will be signed into law. It will then automatically become law 28 days after that.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s English pharmacy board chair, Sandra Gidley, said: “One of the few highlights in what has been a bleak community pharmacy landscape is the fact that the order to decriminalise pharmacists who make inadvertent dispensing errors has now been passed. It still beggars belief that the process to produce and pass the legislation took so many years, but it has also been helpful that the pharmacy minister, Steve Brine, has taken a strong interest in this. It has been an area of focus for the Society in recent years and now we will keep the pressure on and hope that hospital pharmacists will soon be protected in similar fashion.”

The professional regulator has said the stage is now set for further changes so that the threat of criminal prosecution is removed from pharmacists working in other settings. General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) chief executive, Duncan Rudkin, said the GPhC had been consistently clear that, in its view, single dispensing errors, do not constitute a fitness-to-practise concern, if there is no wider pattern of errors or significant aggravating factors.

He said: “We look forward to a governmental consultation next year on removing the threat of criminal sanctions for dispensing errors made by pharmacists working in settings other than registered pharmacies.”

Supervision

Source: Alamy Stock Photo

The key, and still unanswered, question hanging over the Rebalancing Board, which is looking at the future of supervision, at the beginning of the year was whether the UK government intends to allow pharmacy technicians to sell and supply medicines in the absence of a pharmacist.

In March, Ken Jarrold chair of the Board, admitted any change “will not be easy”.

It would be difficult to find a more significant, and contentious, issue facing pharmacists as they grapple with an evolving healthcare environment and changing models. The emergence of new technology, pressures within primary care and the desire of many pharmacists to move into more clinical roles are all key to the supervision debate.

In July, the Pharmacists in Pharmacy campaign group wrote to some Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) Assembly members asking where they stood on supervision. The group believes that a pharmacy without a pharmacist is “just a shop.”

In August, health secretary Jeremy Hunt, attempting to reassure a pharmacist locum, wrote: “The government has not brought forward any proposals to allow pharmacy technicians to supervise pharmacies.”

But in September, a report, written by a working group of the rebalancing board, suggested that current legislation could be changed to allow a “registered pharmacy professional,” which could include a technician, to “take responsibility for “the sale and supply of pharmacy and prescription-only medicines”, was leaked to the press.

The RPS issued a statement saying that a pharmacist should always be present in a pharmacy “apart from short periods of time.” It read: “We do not want to see pharmacies run without pharmacists.” The RPS promised a consultation about supervision in 2018.

The Pharmacists’ Defence Association (PDA) said it was “inconceivable” to have a pharmacy without a pharmacist present and pledged to campaign to “regain the supervision debate” from the Board.

True to its word, in October, the PDA and the community pharmacist association, the National Pharmacy Association (NPA), wrote a joint letter to the Board. They requested that any supervision proposals should be presented to the health secretary only when certain criteria were met — that included “compelling evidence” that patient safety would not be damaged.

Board chairman Jarrold confirmed that supervision would be discussed at its January 2018 meeting, acknowledging that, because of the sensitivity of the issue, the Board had to get it right: “It comes to the heart of what pharmacists feel about themselves and about the future, and that is why we have got to approach it carefully.”

But will the Board get it right in 2018? Board member and RPS president Ash Soni voiced the fears of many that the continued budget cuts and decommissioning of clinical services suggest the sole aim of the supervision review is to get rid of community pharmacy.

He said: “We need confidence and trust that supervision is not an attempt to undermine the professional capabilities of pharmacists”.

Revalidation

Source: Shutterstock.com

Plans to introduce professional revalidation, bringing pharmacists in line with their nurse and doctor colleagues, took a significant step forward this year. Today pharmacists are now much clearer about what is expected of them — even if some do not like what they see.

After the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) published its proposals for consultation in April, there was mounting concern about the move to introduce “peer discussion”.

This will require a pharmacist to have a conversation with a peer about their practice and how it reflects professional standards. Small community pharmacies, specialist pharmacists and locums as well as others were worried they would be unable to find an appropriate person (October).

Their fears were similar to those expressed by nurses and midwives when their regulator proposed the introduction of “peer review” as part of their professional revalidation in the run up to its introduction in 2015.

Reporting back on the results of the consultation in October, the GPhC described feedback as “generally…very positive.” However, the RPS — while telling the profession not to worry and it was there to help —

said the recommendations were too focused on the “process” and were “not robust, future-proof or flexible enough” (July).

And while community pharmacy national negotiator, the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC), was generally supportive of the changes, it was worried about the costs.

From next year, revalidation will be introduced in phases until 2020. The GPhC chief executive, Duncan Rudkin, said the key issue for 2018 will be to make sure that pharmacists “can access the information and guidance they need so they understand what they need to do and when, and are supported through the process.”

The framework for revalidation was formally approved by the GPhC at its council meeting on 7 December, confirming that the new system would be introduced from 30 March 2018.

Dr Catherine Duggan, Director of Professional Development at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society said: “Revalidation will further enable pharmacists to demonstrate their capabilities and be recognised for excellence in healthcare provision. We support this focus on reflection and learning for all registrants and believe it will further enhance the public’s confidence and trust in the profession. We look forward to continuing to work with the GPhC as revalidation further develops in the future to support pharmacists for the benefits of patients.”

While the NPA, which represents community pharmacists, spelt out what its members needed to make revalidation work: “Success in the early phase will depend heavily on the quality and timeliness of feedback given to registrants.”

Primary care integration

Source: Shutterstock.com

Pharmacists in England were urged by the RPS at the beginning of 2017 to find a seat at the table of their local Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs).

STPs, a collaboration between health and social care to create integrated services

“are now where the action is,” Sandra Gidley chair of the English pharmacy board of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) declared in January.

STPs are designed to deliver the government’s Five Year Forward View — its planning blueprint for health services in England up until 2019–2020.

But as 2017 drew to a close, pleas to pharmacists to become involved in their STPs, and calls for STPs to recognise the potential of pharmacists, have often fallen on deaf ears.

In March, the RPS director for England Robbie Turner wrote to all 44 STPs outlining the “strategic benefits” of involving pharmacists on the grounds that “medicines are one of the biggest investments in any STP budget.”

But two months on (May), Turner was forced to admit that pharmacists’ involvement in STPs was “variable, and in the main disappointing.”

Figures published in July by the RPS, PSNC and Pharmacy Voice backed this up. They found that only 10% of local pharmaceutical committees (LPCs) said they had “high levels of involvement” with their STP and a third said they had no opportunity at all to take part.

But as the year progressed, those pharmacists who had taken an active role — such as those in Greater Manchester, where regional devolution has been an advantage, and south east London — found they were influencing the future shape of services. In July, Lancashire LPC, which had “embedded” itself with its local STP from the start, joined in the celebrations when Blackpool and Fylde Coast was named as one of the first districts chosen by the government to develop an “accountable care system” which will take STPs and integration to the next level.

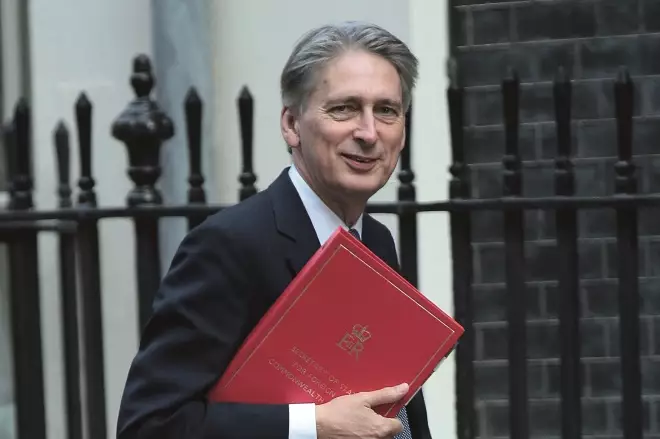

At the end of November, following Chancellor Philip Hammond’s announcement in the autumn budget that £2.6m had been earmarked to support the implementation of STP schemes between now and 2022–2023, Turner wrote to the STP leads again urging them to also include pharmacists in secondary care plans.

In Wales, there are 64 primary care clusters (PCCs) which aim to bring together GPs and other healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, to increase access to care services and reduce pressures on GPs. However, a report from the Welsh Assembly’s Health, Social Care and Sport Committee, published on 13 October 2017, concluded there was still “a long way to go” before PCCs were in a position to serve local communities in the way the government had planned. Mair Davies, RPS director for Wales, said: “The multidisciplinary cluster model must be strengthened and galvanised across Wales so that pharmacists and other health professionals can fully utilise their unique skills to support patients and to contribute to whole system solutions across the NHS.”

The transformation of primary care was also high on the agenda in Scotland during 2017. On 21 August, the Scottish government launched a nine-point plan ‘Achieving excellence in pharmaceutical care: a strategy for Scotland’, which aims to transform both pharmacy and primary care.

The strategy builds on the government’s ‘Prescription for excellence’ document published in 2013, and Scottish chief pharmaceutical officer Rose Marie Parr said the proposals would achieve “world class pharmaceutical care”.

She added: “The commitments and actions in this strategy will help the public and professions alike realise the true value that pharmacy can bring to our communities and daily lives.”

Low-value medicines

Source: Shutterstock.com

Government plans to take low-value medicines and cheaper, over-the-counter (OTC) products off prescription in England to cut the drugs bill, progressed significantly during 2017.

Pharmacy organisations opposed plans to take some OTC products off prescription for people on low income because of the risk of increasing health inequalities (October). But there was a consensus in 2017 that low-value medicines, such as homeopathic and herbal remedies, should no longer be available on prescription (October).

The government wants to take some products off prescription to stop variations in GP prescribing decisions and save money. The results of its recent consultation, due to be discussed by NHS England in November, will form the basis of new statutory prescribing guidelines for clinical commissioning groups (CCGs).

In March, NHS Clinical Commissioners (NHSCC), the organisation which represents CCGs, listed 10 routinely prescribed products which it said could save £128m if they were taken off prescription. The products, it claimed, had little or no clinical value or robust clinical evidence; were costly and had cheaper alternatives, had low NHS priority or had cheaper OTC alternatives. The list included some travel vaccines and gluten-free foods and other products which had cheaper alternatives including fentanyl and liothyronine.

That same month, the initiative was highlighted in the government’s update of its Five Year Forward view, potentially securing its place in NHS long-term plans.

In July, NHS England increased the list of products to 18, classifying them as “relatively ineffective, unnecessary, inappropriate or unsafe”. It said if they were all withdrawn from prescription, £141m could be saved.

That same month it put the list out for public consultation. Views were additionally sought on whether 3,200 prescription items, often available OTC at a cheaper price, should also no longer be available on prescription. Those products included paracetamol, cold treatments, and eye drops which currently cost the NHS £645m annually.

Pharmacy organisations have generally supported moves to take low-value medicines off prescription, acknowledging that the list of 18 products is likely to get longer in 2018.

The government wants to take some products off prescription to stop variations in GP prescribing decisions and save money. At a meeting in November, NHS England board members agreed that draft recommendations, sent out for consultation between July and October, for all 18 products should remain unchanged or be modified or clarified. The consultation formed the basis of new statutory prescribing guidance for clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), which were published on 30 November.

The board also agreed to launch a consultation on curbing prescriptions for the 3,200 OTC products for which they had sought views in the public consultation.

As 2017 draws to a close, worries about taking some OTC products off prescription remain: “Of particular concern is the impact of any changes for those on low incomes, potentially leading to increased use of more expensive urgent-care services,” said Alastair Buxton, director of NHS services at the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee, which negotiates on behalf of community pharmacies.

And he suggested an alternative to a blanket ban on prescribing OTC medicines — the establishment of a national pharmacy-led minor ailments service targeting low income patients exempt from NHS prescription charges.

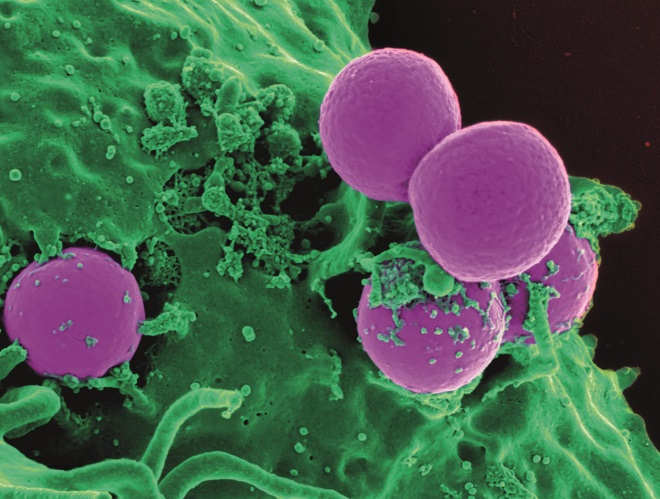

AMR

Source: Wikimedia Commons

There was a stark warning from England’s chief medical officer Sally Davies in the autumn of 2017, when she proclaimed that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) could “signal the end of modern medicine” and, unless action was taken, the world was facing a “post-antibiotic apocalypse”.

Choosing to deliver her chilling words on a world stage, illustrated that if the battle against AMR is ever to be won, it has to be a global fight.

Back in the UK, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) also took a leading role in AMR. It unveiled its antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) campaign in September, encouraging pharmacists to play a greater role in safeguarding antibiotics to minimise the spread of AMR. As part of the campaign, the Society published a new AMS policy and a quick reference guide The Society also relaunched and updated its AMS portal, a hub for healthcare professionals which it runs jointly with University College London, as part of the drive and urged the public to wash their hands for 20 seconds as part of its wider AMR public health message.

Others around the world have also done their bit this year.

In March, the World Health Organisation (WHO) published a list of bacteria that need to be targeted for antibiotic development, hoping to encourage specific AMR research.

Two months later G20 summit leaders agreed to adopt national AMR action plans by the end of 2018, in line with WHO’s Global Action Plan The International Pharmaceutical Federation declared that pharmacists should be encouraging immunisation and implementing antibiotic effectiveness health education campaigns to help control AMR while EU member states, the WHO and the European Medicines Agency organised a joint AMR summit in September.

2017 also saw increased recognition that if the AMR war is to be won, the battle also has to be fought on the animal, food and farming fronts.

In October, EU member states developed a set of outcome indicators to help monitor their progress in combatting AMR.

The collaboration, involving the European Food Safety Authority, the EMA and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, significantly addressed antibiotic consumption and resistance for both humans and animals. The following month (November), WHO called on farmers and the food industry to stop using antibiotics routinely to promote growth and prevent disease in healthy animals.

The call coincided with a review in The Lancet Planetary Health which found interventions that restrict antibiotic use in food-producing animals reduced antibiotic-resistant bacteria in these animals by up to 39%.

But the year concluded with an accusation from the author of a landmark report on AMR, published in May 2016, accusing the UK government of losing focus on the challenge over the past 18 months.

Lord Jim O’Neill voiced his concerns when he formally opened a new AMR Centre in Alderley Park Cheshire on 23 November, which aims to support and accelerate the development of new antibiotics and diagnostics through a fully integrated development capability, offering translational R&D through to clinical proof of concept.

He said: “The UK government has played a mammoth role in getting the ball rolling on antimicrobial resistance all over the world but since the review, some of the intensity of focus has been lost.

“I hope the government rediscovers the passion for championing the AMR Centre and other initiatives that place Britain in a leading role on this issue.”