This content was published in 2002. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Identify gaps in your knowledge

- What social factors influence health?

- What is the reasoning behind health action zones and health improvement programmes?

- How does a knowledge of health inequalities facilitate effective pharmaceutical service delivery?

This article relates to the principles and methodologies of social science relevant to pharmacy. This topic has been included in the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s latest indicative syllabus for pharmacy (available at: www.rpsgb.org.uk/pdfs/eddegnewreq.pdf). You should consider how it will be of value to your practice.

The likelihood of becoming unwell is linked to social as well as biological circumstances. It is not surprising that individuals with few economic resources, and therefore restricted housing, transport and employment opportunities, are at greater risk of ill-health than those who are relatively better off. This is one component of what has been termed the socio-economic model of health, which supplements the bio-medical model. Concomitant with the emergence of this socio-economic model has been the recognition that to improve a population’s health and for everyone to enjoy equal health chances, changes in the way society is organised are required.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC INFLUENCES ON HEALTH AND ILLNESS

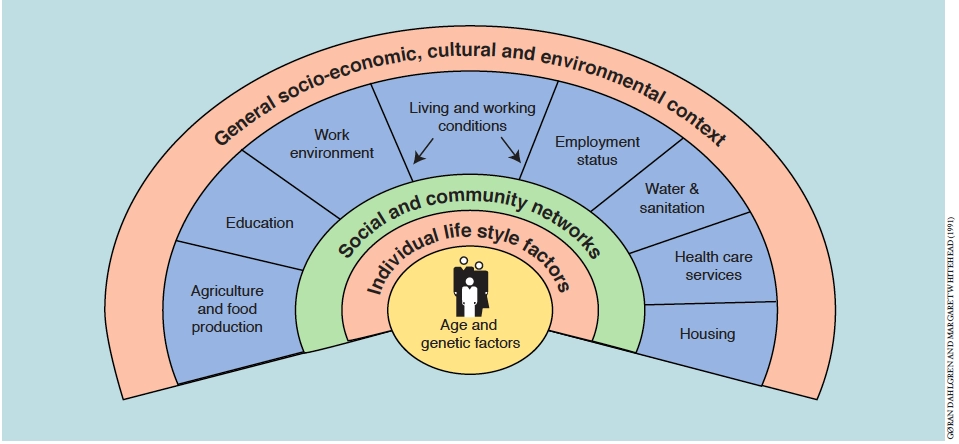

All societies are stratified along cultural, religious and economic lines, and it is apparent that certain diseases are more prevalent among some members of a community than others. Tuberculosis is a prime example. Even our lifespan is influenced by social factors as well as predetermined genetic factors. The multi-layered model of factors determining health status, presented in Figure 1, is a widely accepted interpretation of how an individual’s health is shaped by personal, social, cultural and environmental conditions.

At the centre are immutable factors such as age, sex and genetics. Extending beyond these factors are layers of influence which are modifiable. The innermost layer represents individual lifestyle factors such as smoking, diet and exercise. Next, is a layer of influence representing immediate social networks of friends and family, followed by a layer representing the physical influences exerted by living and working conditions such as employment, housing and the availability of health care services. All these layers of influence are located within a society structured upon capitalist principles which shape the character of our stratified social order.

In western societies, economic stratification is particularly significant in determining health, and socio-environmental influences are particularly pronounced for the socially disadvantaged. Social class has been used extensively as an indicator of material circumstances. A number of classification systems, based on occupation, have been published. In general, these systems have been criticised on a number of counts: for classifying families on the basis of the “head” of the household, non-recognition of the economically inactive and insensitivity to the constantly changing nature of work, such as the rise of service industries, increased part-time working and the increasing number of women in the workforce. Nevertheless, occupational classification is an established and widely used means of relating a person’s socio-economic circumstances to their health status. Table 1 shows the Registrar General’s classification system, which appears in most published studies relating health to social class.

| Social class | Examples of occupation |

| I: Professional | Pharmacist, doctor, lawyer |

| II: Intermediate | School teacher, manager, nurse |

| IIINM: Skilled non-manual | Secretary, shop assistant |

| IIIM: Skilled manual | Carpenter, electrician, cook |

| IV: Partly skilled | Postman, bus conductor, machine operator |

| V: Unskilled | Cleaner, labourer, dock worker |

SOCIAL CLASS AND HEALTH

The Report of the Working Group on Inequalities in Health, submitted to the Secretary of State for Health in 19802 (the Black report) provided extensive evidence of inequalities in health status and in the use, availability and provision of health services between different social groups. The report’s recommendations were largely, targeted at issues where class differences in health were widest, with particular priority given to the eradication of child poverty. These recommendations were considered by the government of the day to be economically unrealistic and were not acted upon. Subsequent reports on health have revealed little if any improvement. Indeed, the recent Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health3 (the Acheson report) found that inequalities had in fact worsened since the publication of the Black report, due in part to the increasing gap between the rich and poor within the United Kingdom.

Inequalities and mortality

In 1981, male life expectancy in the UK was 70.9 years and for females it was 76.8 years. By 1998, these hadincreased to 74.9 and 79.8 years, respectively.4 Currently, on average, women live six years longer than men. Socio-economic and socio-environmental factors can result in variations in mortality rates between nations, within nations and even within communities. For instance, a study in Sheffield5 revealed a difference in life expectancy of almost eight years between the most affluent and the most deprived areas of the city. On average in the UK, a man and woman in social class I have respectively a life expectancy 5.2 and 3.4 years longer than their counterparts in social class V.6 Moreover, statistical evidence indicates that infant mortality rates in the UK (ie, the number of deaths within the first year of life as a proportion of all live births) are nearly twice as great in social class V than in social class I.7 So although, overall, mortality rates have decreased in recent years, risks of premature death continue to be linked to social factors.

Explaining health inequalities

Statistical correlations do not in themselves explain the persistence of inequalities or whether social class determines health, or health determines social class. It is possible, for example, as suggested by some sociologists, that people with long term ill-health move down the occupational ladder towards less well-paid employment and consequently their social class is dependent on health. However, it is also possible that individuals from lower socio-economic groups subscribe to certain dominant values ingrained in their communities, which may include a disinclination actively to protect and promote their health, and the adoption of lifestyles which may have potentially harmful effects (eg, consuming a nutritionally deficient diet, regular excessive alcohol intake or smoking). In this sense, the cause of poor health may be attributed to material and environmental conditions, which support value systems that adversely affect health.

Addressing health inequalities and associated ill-health requires pharmacists to challenge and change ingrained and long cherished cultural practices and attitudes. There is a need for a pragmatic approach because change can be difficult to achieve. Clearly not everyone will be able and willing to modify their practices and beliefs. Even where individuals recognise the importance to health of say, nutrition and diet, the circumstances of material deprivation often limit the available choices of food. Research8 has shown, for example, that poorer people pay proportionately more for their food than those who are more affluent because lacking both transport and resources for a weekly shop at out-of-town shopping facilities, they buy little and often from local shops which are relatively expensive.

Inequalities in health care provision

The decision to seek help is contingent upon the availability of health care. More than thirty years ago, a general practitioner, Tudor Hart9 published evidence of a trend demonstrating that general practitioners who worked in areas where the population suffered the highest mortality and morbidity rates, had the highest patient list sizes and the least hospital support compared with areas exhibiting lower morbidity and mortality rates. Similarly, Hart observed, hospital doctors serving areas with the highest morbidity and mortality had greater caseloads with fewer staff and less equipment, worked in more obsolete buildings, and experienced recurrent crises in the availability of beds and replacement staff. He summarised these trends as the “inverse care law” which suggests that the availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need of the population served. Furthermore, there is evidence of an “inverse prevention law” which suggests that those who are at the greatest risk of ill-health experience least satisfactory access to a full range of preventive services.3 Currently, pharmacies are distributed throughout all communities, including those with material deprivation. It is open to question whether future changes to the pharmacy contract and remuneration of pharmacy services, together with the increasing predominance of multiple pharmacies, will ultimately lead to a shift in distribution of pharmacies from poorer to more affluent areas.

Social integration and health

A characteristic of socio-economically deprived individuals is that their material circumstances prevent them from fully integrating in the wider community, thus perpetuating the cycle of poor health. For example, without access to transport such as a car or an inexpensive and reliable bus service they maybe prevented from making use of out-of-town shopping and leisure facilities, which most people take for granted. Occasionally, some individuals are altogether excluded. In the 19th century, the sociologist Emile Durkheim demonstrated empirically, the idea that social cohesion and integration is good for health. He found that suicide rates were lower in those countries where the citizens were highly socially integrated. Following Durkheim’s connection, the concept of “social capital” emerged. Social capital refers to the degree of trust, integration and cohesion within a society or a community. In recent years the Government has drawn upon these ideas to develop policies to tackle health inequalities. Examples of these policies include health improvement programmes, urban regeneration programmes (eg, New Deal for Communities) and health action zones, which aim to improve health by encouraging the integration of people in deprived areas with the wider community. However, some have argued that this approach masks an underlying more fundamental issue: the need first to address inequalities in health by focusing on narrowing the gap between the rich and poor by means of income redistribution.

PHARMACISTS AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Policies to address health inequalities have traditionally focused on marshalling the services of health workers to address the population’s health needs. For example, wholesale exemption from prescription charges for the less well off has allowed the prescribing of the appropriate medicines to patients irrespective of their cost. Recently, however, policies have focused on the responsibility of individuals for their own health and ill-health. Illness prevention and health promotion (enshrined in the “Health of the Nation”) target lifestyles as being responsible for individuals’ health. Pharmacy policies have responded to this development with a shift away from a medicine-centred approach towards a patient-centred, health promoting approach.

Pharmacists, as players in this new public health movement, are now expected to promote the idea that individuals should be responsible for their own health. Pharmacists offer dietary advice, cholesterol testing, smoking cessation services and even help to minimise the health risks to people who inject illicit substances through needle exchange schemes. To be a pharmacist is to be an effective health promoter. However, this requires pharmacists to appreciate that part of the arrangement whereby people accept responsibility for their own health is that these people are also empowered to question health professionals and reject professional advice and information. As Martin and McQueen10 have observed, the “ . . . essence of the new public health is a healthy scepticism about the role that health professionals, whether biomedical or behaviourally based, can play in the reduction and amelioration of ill health”.

Action: practice points

- Look at the demographics of the area in which you work. What are the main causes of ill-health? Why do you think this is?

- Find out the aims of your local health improvement programme. Write a plan for how you could contribute to the programme.

- Consider the potential of a collaborative approach between yourself and other primary care workers to address local health inequalities. What issues would best be dealt with on a collaborative basis?

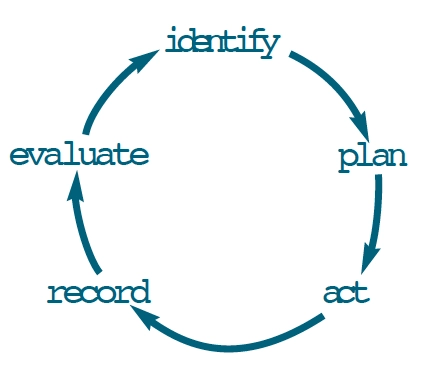

Evaluate

How could your learning have been more effective? What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

Further reading

- Townsend P, Davidson N, editors. Inequalities in health: the Black report (2nd edition). Harmondsworth: Penguin;1990.

- Wilkinson R. Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge; 1996.

References

- Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute for Futures Studies; 1991.

- Black D. Inequalities in health: report of a research workinggroup. London: Department of Health and Social Security;1980.

- Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health. London: The Stationery Office; 1998.

- Office of National Statistics, London: Social Trends; 2001.

- Thunhurst C. Poverty and Health in the City of Sheffield. Sheffield: Environmental Health Department. Sheffield City Council; 1985.

- Pantazis C, Gordon D, editors. Tackling inequalities: where are we now and what can be done? Bristol: The Policy Press; 2000.

- OPCS. Mortality Statistics 1978. London: HMSO; 1982.

- Howard M. Paying the price: Carers, poverty and social exclusion. London: Child Poverty Action Group; 2001.

- Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971; I: 405-12.

- Martin C, McQueen D. Framework for a new public health.In: Martin C, McQueen D, editors. Readings for a new public health. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 1989.p8.