Effective appraisals and support for personal development are good employment practices that can enhance staff performance, staff satisfaction and patient outcomes. If a hospital appraises 20% more staff and trains 20% more appraisers, it is likely to have 1,090 fewer deaths per 100,000 admissions.1 This is why the Care Quality Commission and the Department of Health regard appraisals and personal development plans (PDPs) as essential within NHS organisations.

The NHS staff survey is conducted each year between October and December.2 The survey includes questions to monitor the uptake and quality of appraisals in the NHS. Results from the 2010 survey showed that 77% of NHS staff had an appraisal within the previous 12 months.

The NHS Knowledge and Skills Framework (KSF)3 was designed to enable the growth of services that better meet the needs of patients and the public through investment in staff development. The KSF provides a structure on which to base appraisals and personal development (see Box 1). However, the 2010 staff survey reported that only 34% of NHS staff believed their appraisal was well structured and only 67% had a PDP.2

Box 1: Your appraisal and the KSF

You and your manager are jointly responsible for the appraisal, Knowledge and Skills Framework (KSF) review and personal development plan (PDP). Appraisals should involve a review of competence in relation to the KSF outline for your job. Learning needs are identified in areas of the KSF where competence is lacking and these should inform your PDP. Activities to address particular learning needs should also be included in your PDP.

Some NHS organisations have reported finding the KSF too complex and difficult to integrate into appraisals and PDPs. And so last year the NHS Staff Council undertook work to simplify the KSF to revive its use.4 The council’s recommendations include a greater focus on core KSF dimensions. This seems a sensible approach since these generic dimensions apply to all NHS employees. In contrast, the specific health and well-being dimensions were difficult to apply because they required interpretation to be meaningful for different clinical professions.

Therefore, the simplified approach promotes the use of profession-specific competency frameworks (eg, the general level framework5) alongside the core KSF dimensions. In addition, ensuring that development relates to the “quality” and “service improvement” dimensions enables staff to contribute to the “quality, innovation, productivity and prevention” (QIPP) agenda.6

Despite the simplified approach, some organisations still struggle to implement the KSF. One reason for this could be that line managers are expected to take on aspects of the KSF review cycle that might be better suited to a mentor.

Could mentoring be the link?

Mentoring could improve the integration of the KSF into appraisals and PDPs, thereby maximising the effectiveness of the KSF in achieving its intended outcomes.

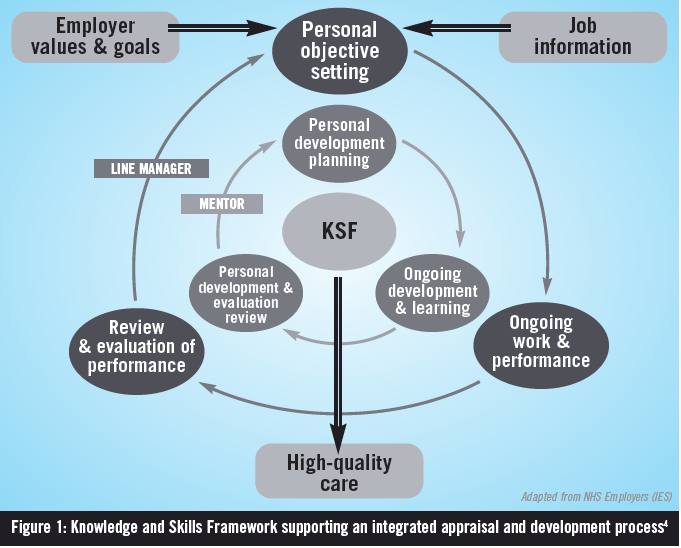

Figure 1 illustrates how the KSF supports an integrated appraisal and development process.4 The outer cycle shows activities that are most suited to a line manager and the inner cycle shows activities that could be undertaken by a mentor.

The same principles could be applied when using any competency framework to support appraisals and PDPs. Box 2 describes the different focuses of managers and mentors and sets out contributions that each can make to appraisals and PDPs.

| MENTOR — FOCUS IS ON HELPING THE MENTEE | MANAGER — FOCUS IS ON GETTING THINGS DONE |

| Focuses on supporting longer-term development for current and future roles | Focuses on the completion of tasks and immediate deadlines |

| Helps the mentee reflect on his or her practice and make a self-assessment of competence in relation to the KSF outline or other competency framework | Assesses performance against standards and conducts appraisals |

| Helps the mentee to see development opportunities and identify learning needs for the PDP | Enables the worker to deliver and perform; identifies performance issues to inform learning needs for the PDP |

| Helps the mentee to set goals and to learn, develop and progress | Sets objectives and checks that these have been met |

| Helps the mentee to monitor his or her progress in relation to the KSF outline or other competency framework | Monitors performance to ensure quality |

To be an effective mentor, it is not necessary to be especially senior within the NHS or to have specialist knowledge of the mentee’s area of practice. The mentor should be an enthusiastic “people developer” who facilitates problem solving and action planning.

Mentors need to stand back, be objective and non-judgemental, and be able to put themselves in the mentee’s shoes. Rather than acting as an expert, mentors take on a supportive role: encouraging mentees to find their own expertise. A mentor can be thought of as a catalyst that stimulates self-directed change, with a belief in the mentee’s ability to solve his or her own problems.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has information for mentors and mentees in the members area of its website,7 connected to a recently launched mentoring service (see Box 3). In addition, the United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association and the Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists have developed a mentoring resource pack, which contains useful tools for setting up and structuring a mentoring session.8

Box 3: Mentor database

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s mentoring service enables pharmacists with various levels of experience practising in any area of pharmacy to benefit from support and guidance.

The online mentor-mentee matching database allows RPS members to find a suitable mentor or to volunteer their services as one. Further information is available at www.rpharms.com/you-and-your-career/mentoring.asp

Both hats?

Some managers think they can mentor individuals at the same time as managing them. This is not recommended because it can be difficult for a manager to balance the managerial focus (getting things done) and the mentoring focus (helping the mentee); and managers can be tempted to be directive and give their own answers to the mentee’s problems. It can also be uncomfortable for an individual to discuss their weaknesses and issues in a full and open manner with their manager, particularly if the issues are contentious.

Matchmaking

Mentoring will have a different meaning for different individuals. For some it will mean a relationship where the mentor guides the mentee on specific topics, and for others it will relate to a wider, less directive relationship.

If there is a mismatch of the expectations of the mentor with those of the mentee, the mentoring relationship could be destined for failure. Therefore, it is important to discuss expectations at the outset of any mentoring relationship. The following questions can be asked by both the mentor and mentee to help decide whether or not they are a suitable match:

- How would you define mentoring?

- What do you want to get out of this mentoring process?

- What do you expect from me?

It is unlikely that the expectations of both parties will be identical, so some compromises may be necessary to find common ground. However, if the expectations of both parties are quite different then it may be better for the mentee to look for an alternative mentor.

The RPS website has some useful checklists for mentors and mentees, which can aid the matching process.9,10

What is in it for a mentee?

The mentor can help the mentee to develop the skills to make a selfassessment of competence against the KSF or other competency frameworks. Learning needs are identified to address gaps in competence and these should be documented in the PDP alongside any learning activities planned to meet these needs. An “Individual knowledge and skills analysis” pack has been developed by London Pharmacy Education and Training11 to help staff develop the ability to produce a PDP with the support of a mentor. The tools within the pack can be applied to the KSF and other competency frameworks.

Mentoring meetings can then focus on supporting the mentee to achieve the learning needs within the PDP, demonstrating evidence of competence and preparing for appraisals.

The mentee should record mentorship actions on the PDP and identify the KSF dimensions or competences that it helps him or her achieve. Particular attention should be paid to how learning activities relate to the “quality” and “service improvement” dimensions — to ensure there is a link to organisational objectives and patient outcomes.

Mentoring should provide a balance of challenge and support. For the mentee it will:

- Shape new and broader perspectives

- Instil greater confidence

- Support the integration of learning into the workplace

- Promote greater self-reliance

- Encourage reflection on practice

Why become a mentor?

Being a mentor can help an individual to fulfil two of the core KSF dimensions: “communication” and “personal and people development”. Mentoring develops an individual’s interpersonal and problem solving skills, selfawareness and ability to challenge assumptions. And, of course, there is the satisfaction of making a positive contribution to the development of an individual and the organisation.

In summary

If trusts are to achieve the required efficiency savings while delivering high-quality patient care, they must ensure that staff are clear about what they are doing and why, and have the skills to do their jobs well.

The KSF defines the knowledge and skills that staff need to apply in their work in order to deliver quality services. Effective appraisals and personal development lead to improved performance and better patient outcomes. Nevertheless, some trusts have found it difficult to link the KSF to appraisals and PDPs.

Mentoring could improve the integration of the KSF into appraisals and PDPs, thereby maximising the effectiveness of the framework in achieving its intended outcomes. Staff using other competency frameworks may also find mentoring to be useful as they work to fulfil their PDPs.

References

- Borrill C, West M. Effective human resource management and patient mortality. A toolkit for use by HR professionals in the NHS. NHS Modernisation Agency Leadership Centre. 2004.

- Care Quality Commission. NHS staff survey 2010: key findings. www.cqc.org.uk/nhs-staff-have-their-say-results-national-survey-arepublished (accessed 20 October 2011).

- Department of Health. The NHS Knowledge and Skills Framework (NHS KSF) and the development review process. October 2004. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/ DH_4090843 (accessed 17 March 2011).

- NHS Employers. Appraisals and KSF made simple — a practical guide. November 2010. www.nhsemployers.org/Aboutus/Publications/Pages/AppraisalsAndKSFMadeSimple-ApracticalGuide.aspx (accessed 17 March 2011).

- Competency Development and Evaluation Group. General level framework. www.codeg.org/frameworks/general-level-practice (accessed 20 October 2011).

- NHS Improvement. Quality, innovation productivity and prevention (QIPP) www.improvement.nhs.uk/Default.aspx?alias=www.improvement.nhs.uk/qipp (accessed 20 October 2011).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Mentoring. www.rpharms.com/you-andyour-career/mentoring.asp (accessed 17 October 2011).

- United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association and Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists. Mentor Resources. www.docstoc.com/docs/25744280/ Resources—UKCPA–GHP-Mentor-Database (accessed 17 October 2011).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Checklist for mentors. www.rpharms.com/ checklists/checklist-for-mentors.asp (accessed 17 October 2011).

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Checklist for mentees. www.rpharms.com/checklists/checklist-for-mentee.asp (accessed 17 October 2011).

- London Pharmacy Education and Training. Individual Knowledge and Skills Analysis pack. 2011. www.lpet.nhs.uk/ProfessionalDevelopment/ CPDSupport/KSFLearningResources.aspx (accessed 4 October 2011).