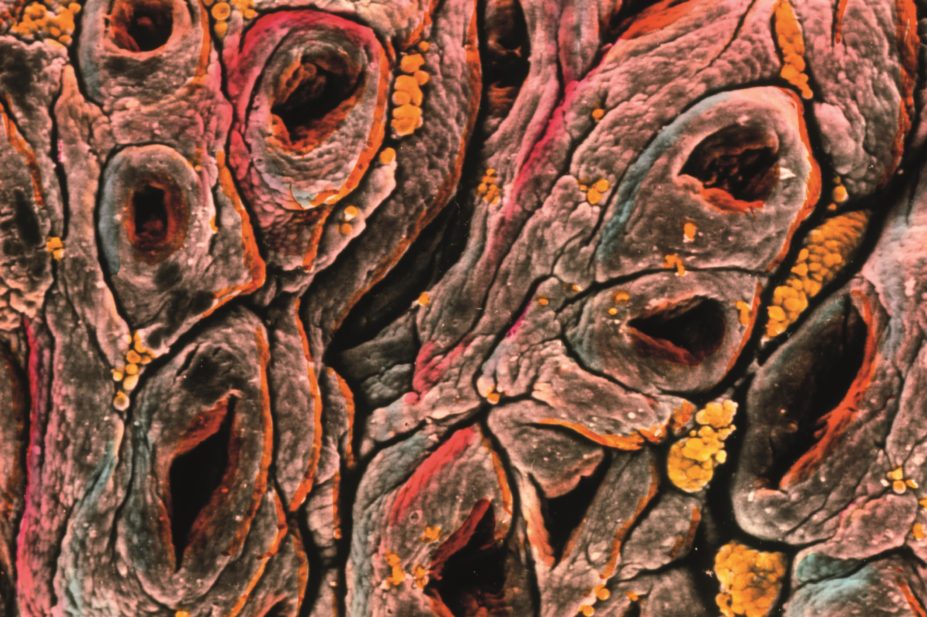

Prof. P M Motta & F M Magliocca / Science Photo Library

For Alice Bast, the first sign of trouble is prickly skin and a flushed face. This gives way to diarrhoea, a terrible headache and fatigue that can last for three days. Bast has coeliac disease, and these are the ill-effects of gluten, a protein found in wheat and other grains that causes an inflammatory reaction in her body. The only current treatment is to avoid gluten, which means steering clear of common foods such as bread and pasta for life.

Alice Bast, head of the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness, based in Ambler, Pennsylvania, says that avoiding gluten is difficult

Despite her vigilance, and the current proliferation of gluten-free choices on supermarket shelves and restaurant menus, Bast still occasionally gets “glutened”.

“I like that I can avoid gluten to feel better. But the reality is it’s really, really difficult to do,” she says.

Bast is not the only one who finds it tough: the perceived burden of a gluten-free diet ranks just below that of patients with kidney disease requiring dialysis, which is considered the worst of all[1]

.

There is hope. New drug treatments for coeliac disease are now being tested in clinical trials: some are designed to be taken alongside a gluten-free diet, protecting against the occasional slip-up, whereas others offer the possibility of ditching the diet altogether.

With a drug option, I wouldn’t have to worry about every morsel of food that goes into my body

“With a drug option, I wouldn’t have to worry about every morsel of food that goes into my body,” says Bast, who founded and heads the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness (NFCA), based in Ambler, Pennsylvania.

But drugs need approval, and there is debate over which study outcomes should be used to measure a treatment’s success. Coeliac disease is notoriously variable; symptoms differ widely, and come and go unpredictably. More objective measures, such as biomarkers in the blood that can be used as indicators of disease status, or signs of intestinal damage, do not necessarily correlate with symptoms. What should regulators focus on — treating symptoms or treating the underlying disease process?

Alessio Fasano, director of the Center for Celiac Research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discovered coeliac candidate drug larazotide

“This is the most debated part of the story, and I’m sure if you talk to five people, they will give you five different opinions,” says Alessio Fasano, director of the Center for Celiac Research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Gut reaction

Around 1% of people in the United States and Europe have coeliac disease, and 20 million people are estimated to have the disease worldwide. Prevalence is on the rise — one study found a four-fold increase compared with 50 years ago[2]

.

Coeliac disease develops when the immune system mistakes gluten for a foreign invader, attacking it and damaging the intestinal wall — which is essential for absorbing nutrients from food — in the process. Symptoms range from stomach aches, bloating and diarrhoea, to headaches, fatigue and, in children, growth deficits. What you get varies from one person to the next and some show no symptoms at all.

Yet coeliac disease sufferers are united by their genes, with most carrying a specific genetic variant in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene known as HLA-DQ2, and the remainder carrying another variant, HLA-DQ8. These genetic variations seem to predispose people to mount an immune response to gluten. Diagnosis relies on blood tests showing antibodies to components of gluten, as well as a biopsy of the small intestine demonstrating damage in the form of flattened villi, the finger-like projections that line the intestinal wall.

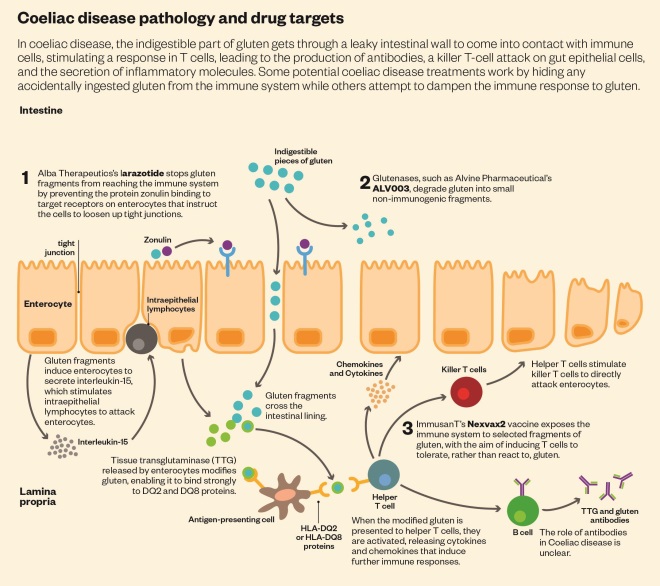

Normally, when gluten-containing food is eaten, the indigestible part of gluten — gliadin — is swept along the digestive tract to be excreted. But in coeliac disease, gliadin gets through a leaky intestinal wall to come into contact with immune cells. HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 molecules bind the gliadin and stimulate an immune response in CD4 T cells, leading to the production of antibodies, a killer T-cell attack on gut epithelial cells, and the secretion of inflammatory molecules.

After cutting out gluten, someone with coeliac disease can often feel better quickly and the levels of antibodies in their blood will go down. But intestinal healing can take years, and any lapses can prolong the process: around 70% of coeliac disease patients still show signs of intestinal damage after two years on a gluten-free diet[3]

. The long-term consequences of an unhealed gut have been linked with an increased risk of lymphoma, hip fractures and osteoporosis, but no change in mortality.

Hiding in plain sight

Some potential coeliac disease treatments work by hiding any accidentally ingested gluten from the immune system. Sufferers would continue on the gluten-free diet, prophylactically taking a pill before every meal.

This is not a passport to eating gluten with impunity

“This is not a passport to eating gluten with impunity,” says Joseph Murray of The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Murray has been involved in clinical trials of these treatments.

One way of dodging the immune system would be with an enzyme that chops gluten into shorter, unrecognisable pieces. The ‘glutenase’ furthest in development is San Carlos, California-based Alvine Pharmaceutical’s ALV003. When taken with gluten amounting to half a slice of bread every day for six weeks, ALV003 prevented intestinal damage in coeliac disease sufferers in a phase IIa study[4]

. However, compared with placebo, the drug did not significantly change levels of coeliac disease markers in the blood or reported symptoms.

Yet the condition of the gut is a sensitive indicator of a drug’s effects on the underlying pathology of coeliac disease, says Markku Mäki of the University of Tampere, Finland, who led the trial. Intestinal damage often precedes symptoms, follows swiftly after a gluten challenge, and is more easily detected than changes in the raft of symptoms associated with coeliac disease.

“A biopsy gives us an essential readout of whether the drug is doing some good,” he says, noting that an exclusive focus on symptoms may result in a drug that masks persistent gut damage and inflammation.

A phase IIb study (designed to assess drug efficacy rather than determine dosing, as in phase IIa study) has recently concluded, in which around 500 people with coeliac disease took ALV003 or placebo while following their usual gluten-free diet. The results have not yet been published, but the study is using levels of intestinal damage as its primary outcome.

By contrast, clinical trials of another candidate, larazotide acetate, are focusing on symptoms. Larazotide keeps gluten out of the immune system’s reach by preventing it from getting past the intestinal wall. The ability of the drug to inhibit gut permeability was discovered by Fasano, and Alba Therapeutics, based in Baltimore, Maryland, is leading the clinical trials.

So far, the results have been encouraging. Two studies showed that larazotide limited gluten-induced gastrointestinal symptoms[5]

,[6]

, and this effect was confirmed in a phase IIb study of more than 300 people on a gluten-free diet[7]

.

But coeliac disease sufferers should not expect a treatment to arrive too quickly. Alba Therapeutics is currently looking for funding partners for a planned phase III study. With no other drug having been approved for coeliac disease, there is no model for drug companies to follow, making investment a risky business.

Taming T cells

Another treatment strategy is to dampen the immune response to gluten. If successful, this could provide an alternative to a gluten-free diet.

If you can prevent the T cells from being reactive to the gluten, then you can stop the pathology

Bob Anderson, chief scientific officer at ImmusanT

Bob Anderson, chief scientific officer at ImmusanT, is developing a vaccine that dampens the immune response to gluten

“If you can prevent the T cells from being reactive to the gluten, then you can stop the pathology. Then in principle, it wouldn’t matter how much gluten you eat,” says Bob Anderson, chief scientific officer at ImmusanT, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Anderson and colleagues were the first to identify the gliadin components responsible for triggering a T-cell response in coeliac disease[8],[9]

.

ImmusanT’s Nexvax2 vaccine aims to retrain the immune system through low level, repeated exposure to these offending molecules — similar to how allergy shots work to desensitise the immune system to allergens.

So far, the vaccine has been tested in 116 people with coeliac disease on a gluten-free diet in three phase I studies. The results have not yet been published, but the vaccine was deemed safe and well enough tolerated to warrant phase II trials, which will start later in 2015. Anderson says the new trials would be looking for changes in symptoms, blood biomarkers and on gut biopsy.

Editorial advisers: Alessio Fasano and Joseph Murray

Measuring success

The different approaches taken for different drugs begs the question: on which outcome should coeliac disease trials be focused? Trials are designed to look at the effects of a treatment on a single primary endpoint. Other, secondary endpoints can also be investigated, but if the trial does not meet the primary endpoint, it fails. So researchers need to choose wisely.

There’s not one endpoint that measures the disease, like blood sugar does for diabetes

“Our outcomes are tricky,” says Sheila Crowe, head of the Celiac Disease Clinic at the University of California, San Diego Health System. “There’s not one endpoint that measures the disease, like blood sugar does for diabetes.”

Sheila Crowe, head of the Celiac Disease Clinic at the University of California, San Diego Health System, likes to see symptom improvement and reversal of any nutritional abnormalities in her patients

As a clinician, Crowe likes to see symptom improvement, decreases in coeliac-disease-specific antibodies and the reversal of any nutritional abnormalities in her patients. Only occasionally does she re-biopsy them.

But drug trials demand more than clinical judgement, and each feature of coeliac disease — symptoms, blood biomarkers and gut biopsies — may fall short in capturing a drug’s benefits. Gut biopsies are invasive, may miss the damaged portion of small intestine, and the results can be misread. Blood markers take time to index gluten exposure, do not necessarily reflect gut damage and may be too low in a person already on a gluten-free diet to detect a drug’s effects. Symptoms may flare up quickly after gluten exposure, but they vary and do not necessarily reflect the condition of the gut. No standard questionnaire is in use to measure coeliac disease-specific gastrointestinal symptoms.

In March 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) convened a workshop of researchers, regulators and patient advocates to discuss how best to define the clinical benefit of a drug for coeliac disease. The point of the meeting was not to come up with a consensus, but some felt that the FDA was leaning towards patient-reported outcomes — how patients themselves feel about their symptoms and quality of life.

“They made it very clear that the primary outcome has to be clinical improvement or prevention of symptoms when people are exposed to gluten,” says Fasano, who spoke at the meeting.

Fasano probably read the mood right. “The main goal is to demonstrate that a given treatment has a clinically meaningful effect on how patients feel, function or survive,” says FDA spokesperson Tim Irwin in an emailed statement. But, he acknowledges, “it will also be important to demonstrate that the drug has a favourable effect on the underlying disease, which is usually measured by histological assessment [of the intestine]”.

But some researchers suggest a middle ground that may involve establishing a drug’s benefit on the intestine in earlier trials, with symptoms becoming the primary outcome in later stages. “Gut histology probably needs to be part of the package for determining [the] safety and efficacy of a drug, but I don’t know that it has to be the primary endpoint,” Murray says.

As a patient, Alice Bast wants both: “As long as it is going to heal my villi and help me with my symptoms, I would take a drug.”

References

[1] Shah S, Akbari M, Vanga R et al. Patient perception of treatment burden is high in celiac disease compared with other common conditions. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2014;109:1304–1311. doi:10.1038/ajg.2014.29

[2] Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2009;137:88–93. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.059

[3] Rubio-Tapia A, Rahim MW, See JA et al. Mucosal recovery and mortality in adults with celiac disease after treatment with a gluten-free diet. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2010;105:1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.10

[4] Lahdeaho, Kaukinen K, Laurila K et al. Glutenase ALV003 attenuates gluten-induced mucosal injury in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1649–1658. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.031

[5] Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Abdallah HZ et al. A randomized, double-blind study of larazotide acetate to prevent the activation of celiac disease during gluten challenge. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2012;107:1554–1562. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.211

[6] Kelly CP, Green PH, Murray JA et al. Larazotide acetate in patients with coeliac disease undergoing a gluten challenge: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2013;37:252–62. doi:10.1111/apt.12147

[7] Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Green PH et al. Larazotide acetate for persistent symptoms of celiac disease despite a gluten-free diet: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1311–1318. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.008

[8] Anderson RP, Degano P & Godkin AJ. In vivo antigen challenge in celiac disease identifies a single transglutaminase-modified peptide as the dominant A-gliadin T-cell epitope. Nature Medicine 2000;6:337–42. doi:10.1038/73200

[9] Tye-Din JA, Stewart JA, Dromey JA et al. Comprehensive, quantitative mapping of T cell epitopes in gluten in celiac disease. Science Translational Medicine 2010;2:41ra51. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3001012