Mclean/Shutterstock.com

Being labelled as having a penicillin allergy may seem harmless, but for those who fall ill, it increases the likelihood that they will be treated with broad-spectrum, non-penicillin antibiotics, which are linked to a higher incidence of antibiotic resistance and poorer health outcomes.

“Patients with a penicillin allergy record are much more likely to be treated with macrolides, tetracyclines, clindamycin, cephalosporins and quinolones, and some of those are more associated with resistance,” explains Jonathan Sandoe, an associate professor of microbiology at the University of Leeds.

“For example, in Streptococcus pneumoniae — one of the most common causes of community-acquired pneumonia — there’s much more resistance to macrolides than to penicillins.”

Around 10% of the general population claim to have a penicillin allergy, often because of a skin rash that occurred in childhood, and numbers appear to be increasing[1]

. An analysis of hospital episode statistic data by The Pharmaceutical Journal reveals that, between 2012/2013 and 2018/2019, the number of hospital admissions in England where the patient had a recorded history of penicillin allergy almost doubled, from 575,000 to 1.1 million.

Patients with a penicillin allergy record are much more likely to be treated with macrolides, tetracyclines, clindamycin, cephalosporins and quinolones, and some of those are more associated with resistance

As a proportion of total hospital admissions in England, those with a history of penicillin allergy rose from 4% to 6% over the same time period.

However, studies indicate that penicillin allergy could potentially be excluded in 90% of cases and, even for those who have had a reaction to penicillin in the past, the risk of allergy wanes over time as allergic antibodies disappear[1]

[2]

. Just 20-30% of those who have previously reacted to penicillin will do so in the same way ten years later[2]

.

The Department of Health and Social Care is calling for a reduction in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics as part of the UK’s five-year national action plan to tackle antimicrobial resistance, and experts say that reassessing and removing penicillin allergy labels where safe to do so, also known as ‘de-labelling’, could have a significant impact on achieving that goal[3]

. This is a complicated area, but there are some who are looking at ways of making de-labelling routine in the NHS.

Impact of penicillin allergy labels

Numerous studies have highlighted the link between penicillin allergy labels and poorer outcomes for patients.

A 2019 study which collected data on penicillin, carbapenem, monobactam and clindamycin usage, and associated adverse reactions, found that Clostridium difficile infection is more common with broader spectrum antibiotic exposures, such as carbapenems or clindamycin[4]

.

In 2018, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence urged healthcare staff to check that only bona fide penicillin allergies are recorded, after research published in the BMJ highlighted that people with a penicillin allergy label were almost 70% more likely to develop methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and 26% more likely to develop C. difficile

[5]

.

“If you look at the evidence around the risks associated with having a penicillin allergy and getting an alternative treatment, [there are] higher rates of resistant infections and a higher incidence of C. difficile [infection],” says Jacqueline Sneddon, an antimicrobial pharmacist, project lead of the Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG) and chair of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s antimicrobial expert advisory group.

“So, there are potential adverse consequences for patients [who receive] an alternative [to penicillin],” she warns.

We know in our hospital that [if you have a penicillin allergy label], your risk of being given meropenem goes up around six-fold

“We know in our hospital that [if you have a penicillin allergy label], your risk of being given meropenem goes up around six-fold,” says Neil Powell, consultant antimicrobial pharmacist at Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust.

Meropenem, a carbapenem, is on the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) ‘reserve’ list of antibiotics that should be used as “last resort” options, while many of the penicillins are on the ‘access’ list, meaning they are recommended as a first treatment option[6]

.

Powell says that penicillin allergy has also been found to increase the use of vancomycin — an antibiotic on the WHO’s ‘watch’ list — which in turn drives the evolution of vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

“So, the penicillin allergy label does drive more second-line or broad-spectrum antibiotic use. These antibiotics seem to be more toxic and are associated with higher treatment failure rates,” he adds.

Determining true penicillin allergy

Unfortunately, according to Powell, testing people for ‘true’ penicillin allergy is a “laborious process” that requires specialist input which is not always available.

“It is meant to be delivered by allergy services — immunologists — but there’s no capacity to do that,” he explains.

“With an increasing number of patients coming in [with suspected penicillin allergy] and no solution to this problem currently with the immunologists, we need to work out ways of moving this out of immunology and into general medicine — medics, pharmacists et cetera — to try to tackle this.”

With an increasing number of patients coming in [with suspected penicillin allergy] and no solution to this problem, we need to work out ways of moving this out of immunology

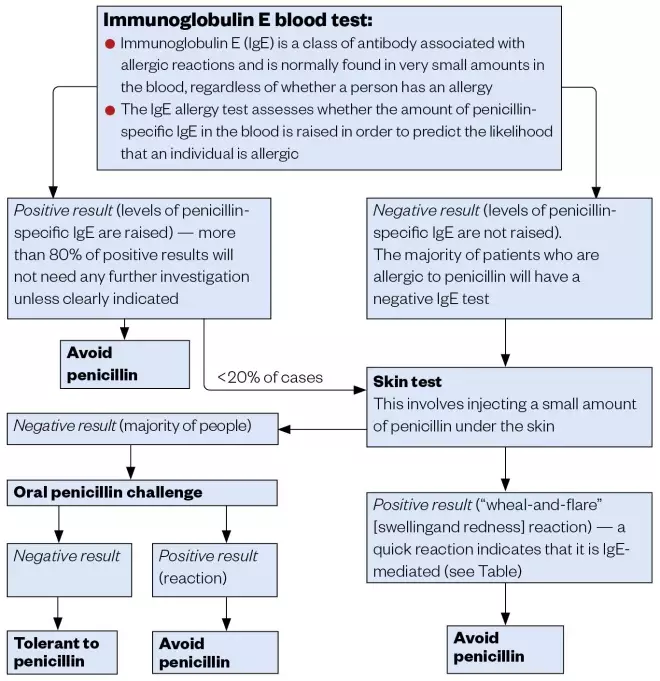

Testing for a true penicillin allergy starts with an immunoglobulin E (IgE) test. IgE is a class of antibody associated with allergic reactions and is normally found in very small amounts in the blood, regardless of whether a person has an allergy (see Figure).

Figure: Testing for a penicillin allergy

The majority of people who have a positive IgE result will be confirmed as being allergic and will not undergo any further investigation unless it is clearly indicated. If the result is negative, a skin test will then be carried out, which involves injecting a small amount of penicillin under the skin.

“If the [patient] reacts to [the skin test] quickly, that’s likely an IgE-mediated reaction,” says Powell. “And then the [immunologist] won’t go any further.”

“If you have a negative skin test, which the majority [of people] do … then they would go on to [do] an oral challenge. If the patient doesn’t react to the oral challenge then you can [confirm that] they are not allergic to penicillin”.

However, Powell adds that it is possible to go straight to a supervised oral challenge for people with a history of a low-risk allergy, such as a delayed skin reaction, without having to do a skin test. This means that penicillin allergy testing could be moved out of immunology and into other areas of the hospital.

Moving away from immunology

In Scotland, Sneddon is piloting a process to de-label penicillin allergy in acute hospitals using an oral penicillin challenge.

“We’ve developed a risk-based algorithm which helps us to identify which people are at low risk of having a true allergy ,” she explains.

The test involves giving low-risk patients a single dose of penicillin and then monitoring them closely to see if they have a reaction. If they fail to have a reaction, this is documented in their notes and communicated to the patient and their GP.

We’ve developed a risk-based algorithm which helps us to identify which people are at low risk of having a true allergy

“The process involves lots of communication with the patient about the practicalities of the test and the benefit of a negative test,” Sneddon explains.

The SAPG aims to launch a national toolkit towards the end of 2020 to help clinical teams in Scotland safely carry out penicillin allergy de-labelling.

Louise Savic, a consultant anaesthetist at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust with a special interest in drug allergy and chair of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) penicillin allergy de-labelling guideline group, says that penicillin allergy is a “big problem” in surgical patients.

“We know that at least 10–15% [of patients] have this label and will [consequently] get second-line antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery,” she explains.

“And that causes us a problem because the second-line antibiotic they get, which is teicoplanin in this country, is quite allergenic — more so than any other drug we give in the perioperative period.”

But an even bigger problem, she says, is how this is feeding into antimicrobial resistance. According to Savic, in the surgical population alone, millions of doses of antibiotics are given to help cope with surgical-site infections; if 10% of the population has a penicillin allergy label and are getting alternatives, then that is potentially millions of second- and third-line, broad-spectrum antibiotics that are being given, in most cases, “completely unnecessarily”.

“We know that there are all these patients with labels — and we know that the vast majority aren’t correct — but we don’t have enough allergy specialists to test all of the people in the country.”

We know that there are all these patients with labels — and we know that the vast majority aren’t correct — but we don’t have enough allergy specialists to test all of the people in the country

In Savic’s line of work, preoperative assessment clinics are an appropriate place to assess patients with a penicillin allergy label, but some countries, including the United States and Australia, have explored carrying out these tests in emergency departments, inpatient areas and oncology, with some success[7]

.

There is also the potential for penicillin allergy de-labelling to be carried out in primary care, but Savic says that views on this are “a bit mixed”.

“There’s really good evidence in children. They’re much more likely to have viral rashes at the time of taking penicillin, so they probably can be de-labelled very safely in the community.

“[But] I think there are some problems with de-labelling adults in the community. The biggest of those is going to be that GPs don’t have time to do their day job, let alone take on an additional role,” she says. “[Plus,] I’m not totally convinced that it’s the safest place for it to be done.”

As Savic explains, if you give enough people a challenge test, eventually somebody will have an allergic reaction.

Barriers to de-labelling

In a recent study, Savic recruited more than 26,000 surgical patients and anaesthetists to determine understanding of penicillin allergy and the potential barriers to de-labelling.

“We looked at all the people within that group who had a penicillin allergy label and stratified them into low-, intermediate-, or high-risk of true allergy, based on a detailed history,” she explains.

“[We were] trying to work out what the barriers [were, whether] the patients wanted testing, how many would be suitable for a direct [oral] challenge and what anaesthetists thought about the label.”

The research highlights that it is clinicians and healthcare workers who might provide the biggest barriers to labelling. “Patients generally want testing, but there’s still a lot of anxiety among clinicians,” Savic says.

Sandoe is the co-chief investigator on a National Institute for Health Research-funded study, due to end in October 2023, called the ALABAMA (Allergy antibiotics and microbial resistance) study, which aims to find out whether people with a penicillin allergy label in their GP health records really do have an allergy, and if the number of patients wrongly labelled can be reduced[8]

.

“ALABAMA is an open-label, randomised controlled trial of penicillin allergy testing in patients in primary care,” he explains.

“Patients with a penicillin allergy record who are likely to need an antibiotic in the future are randomised to either carry on usual clinical care or go to an immunology clinic and be formally penicillin allergy assessed [and potentially de-labelled].”

Following randomisation, the researchers will look at how individuals respond to treatment when prescribed antibiotics for a condition where penicillin would normally be considered first line.

“It is a trial of a complex intervention,” says Sandoe, speaking in a personal capacity. “It’s not just comparing test A with test B, or drug A with drug B, we’re actually looking at the whole process of testing as well as the effect on patient health outcomes.”

The study has also revealed many of the barriers preventing penicillin allergy de-labelling. These range from overarching practical barriers, including the lack of capacity in the NHS, to local barriers, such as GPs often not referring patients for testing because they are uncertain about the processes involved and how they would interpret the results.

However, as with Savic’s findings, there is a willingness to be tested among patients and a willingness to take penicillin if a test comes back negative.

They don’t like having this allergy label and they often don’t know why it’s there

“They don’t like having this allergy label and they often don’t know why it’s there, for example, they were just told that they had a reaction in childhood, so many patients are positive about being tested,” says Sandoe.

The literature, he adds, indicates that after excluding patients with anaphylaxis, which has been reported as being less than 1%, more than 95% of people with an allergy record who are tested turn out not to be allergic after all[9]

,[10]

.

Moving forward

The BSACI, which has wide stakeholder engagement from several royal colleges, plans to produce guidelines later in 2020, which will outline which patients can safely be de-labelled by non-specialists, what methods they should use, and what the safety and training standards should be, in order to encourage more widespread de-labelling.

“I think there’s a role for a wide range of people who aren’t primary allergy specialists — and that’s pharmacy, that’s nursing, it’s other medical specialties. I don’t think this is a problem owned and delivered by doctors alone, it has to be cross specialty,” says Savic.

Sneddon agrees that pharmacists should have a major role in the de-labelling process.

“From a pharmacist perspective, the screening element it likely to be their main role … they could screen to see if the patient is low-risk and then pass on the details to the specialist to make the decision as to whether they want to offer the de-labelling test or not,” she says.

From a pharmacist perspective, the screening element it likely to be their main role

As part of his PhD, Powell is trying to assess how to motivate and encourage doctors, nurses and pharmacists to take allergy histories on the ward to help identify those who are at low risk of penicillin allergy and who could be given penicillin under supervision.

“What tools do they need to safely do it, and what reassurance do they and the organisation need to [help them understand that] this is a safe thing to do, [and that] patients are up for it?”

While there are pockets across Great Britain where important work is being carried out in the area of penicillin allergy, this needs to be widespread in order to have a significant impact on improving antimicrobial stewardship and reducing adverse healthcare outcomes.

“The upshot is that we’re seeing twice as many patients with this label than we used to,” says Powell.

Antibiotic resistance, increased readmission rates and lengths of stay, and admissions to intensive care units are all things associated with penicillin allergy labels, he adds.

“If you think about the creaking healthcare service in terms of volume of patients, we’re unnecessarily [adding to this] because of these labels.”

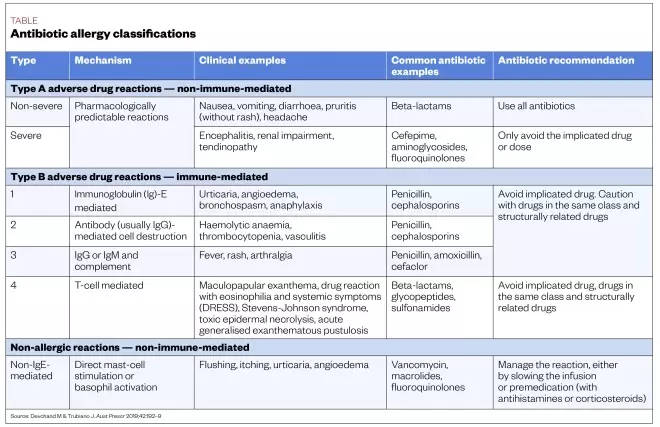

Table: Antibiotic allergy classifications

References

[1] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg183/resources/drug-allergy-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-35109811022821 (accessed June 2020)

[2] Jethwa S. Pharm J 2015;295:7878. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2015.20069170

[3] Department of Health and Social Care. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/784894/UK_AMR_5_year_national_action_plan.pdf (accessed June 2020)

[4] Liang EH, Chen LH & Macy E. Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; pii:S2213-2198(19)31017-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.11.035

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018. Available here: https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/double-check-patients-with-penicillin-allergy-to-avoid-increased-mrsa-risk (accessed June 2020)

[6] World Health Organization. 2019. Available here: https://www.who.int/medicines/news/2019/WHO_releases2019AWaRe_classification_antibiotics/en/ (accessed June 2020)

[7] Maguire M, Hayes B, Fuh L et al. World Allergy Organ J 2020;13(1):1000093. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100093

[8] National Institute for Health Research. 2019. Available here: https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/RP-PG-1214-20007 (accessed June 2020)

[9] Sacco K, Bates A, Brigham T et al. Allergy 2017;72:1288-1296. doi: 10.1111/all.13168

[10] Savic L, Khan D, Kopac P et al. Br J Anaseth 2019;123(1):e82–e94. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.026