JL/The Pharmaceutical Journal

With almost 700 novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) recorded in Europe, and more emerging every week, the market for them is evolving rapidly, presenting a significant challenge to policymakers across the world.

In the UK, the Psychoactive Substances Act (PSA) came into force in May 2016, making it an offence to produce, supply or offer to supply any psychoactive substance if it is likely to be used for its psychoactive effects, regardless of its potential for harm[1]

.

The concerns that myself and colleagues had when the Act was introduced was that closing down the head shops wouldn’t end the problem

The Act captures all psychoactive substances that are not controlled by the Misuse of Drugs Act (MDA) 1971 or are otherwise exempt, such as medicines, tobacco and caffeine[2]

.

The main intention of the PSA was to shut down shops and websites that traded in what were then known as ‘legal highs’, now widely recognised as NPSs (see Panel 1). While a 2018 Home Office review into the PSA found that high street ‘head’ shops have been largely eliminated, it revealed that NPS sales had been driven elsewhere (see Figure). According to a Europol study, the UK is still one of the leading dark web sellers of NPSs in Europe[3]

.

“The concerns that myself and colleagues had when the Act was introduced was that closing down the head shops wouldn’t end the problem. It would just drive the problem underground, and that’s what happened,” says Alex Stevens, professor of criminal justice at the University of Kent, who specialises in research on drug policy and the link between drugs and crime.

Panel 1: What are novel psychoactive substances?

Novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) are any substances that are capable of producing a psychoactive effect in the user[4]

. The psychoactive effect of the NPS is generated by stimulation or depression of the person’s central nervous system and affects the user’s mental functioning as well as their emotional state.

NPSs often mimic the effects of traditional drugs controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and, although once referred to as legal highs, the chemicals in NPSs are frequently neither legal, nor safe for human consumption[5]

.

Before the introduction of the Psychoactive Substances Act in 2016, NPSs were generally sold online or on the high street in ‘head’ shops, which may have also had online businesses. There were also some reports of them being sold in non-specialist outlets, such as newsagents or petrol stations[5]

. In addition, NPSs are sold on the dark web and on the illicit market, sometimes under their own name and sometimes falsely as illicit drugs, such as heroin and ecstasy[6]

.

As these substances continue to grow at an alarming rate, in both number and complexity, questions have been raised as to whether the government is approaching the problem in the right way and whether NPSs could be tackled more effectively by focusing not just on those who sell them, but on those who use them too.

Growing market

By the end of 2017, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction was tracking more than 670 NPSs that had been identified in Europe — from synthetic cannabinoids and stimulants to opioids and benzodiazepines.

Gino Martini, chief scientist at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, says he is particularly “appalled” by the widespread use of nitrous oxide. Commonly known as laughing gas, this NPS, according to the Home Office review, does not appear to have been affected by the PSA[3]

.

Source: MAG / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Gino Martini, chief scientist at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, believes nitrous oxide is a gateway to harder drug substances

“The legislation is a little bit irrelevant because it’s not being controlled — I use the word epidemic — it really is … it’s not being policed and the access to the canisters is far too easy.

“The general opinion is that these nitrous oxide canisters are safe. They’re not safe, and they can have adverse consequences for people’s health,” says Martini.

“I also think they’re a gateway to harder drug substances,” he adds.

The list of NPSs appearing on the drug market continues to grow and, on average, around one additional NPS is reported each week in Europe[5]

. But these are just the substances that have been reported. According to the Home Office review, the emergence of new NPSs in the UK has not ceased since the PSA was introduced, perhaps because of incentives to develop new substances that evade the MDA 1971[3]

.

Over the past year we’ve seen an increase, quite dramatically in some areas, in the number of police call-outs and the number of ambulance call-outs related to synthetic cannabinoids, commonly known as ‘Spice’

“Over the past year we’ve seen an increase, quite dramatically in some areas, in the number of police call-outs and the number of ambulance call-outs related to synthetic cannabinoids, commonly known as ‘Spice’,” explains Stevens.

Data from West Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust show a surge in call-outs linked to use of ‘Spice’ (a street name that has been applied to many different synthetic cannabinoids). Numbers went up from 2,890 call-outs between January 2017 and July 2017, to 3,233 call-outs in the same period a year later[7]

. A similar pattern was seen in figures from South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust, which saw a rise from 157 call-outs between August 2016 and July 2017, to 960 call-outs between August 2017 and July 2018. In 2017, Manchester was overwhelmed by users of Spice in a so-called ‘zombie epidemic’.

Source: Courtesy of Amira Guirguis

Amira Guirguis, a pharmacist and senior lecturer in pharmaceutical chemistry in the Psychopharmacology, Drug Misuse and Novel Psychoactive Substances Research Unit at the University of Hertfordshire, says that education and training is needed at every level

Amira Guirguis, a pharmacist and senior lecturer in pharmaceutical chemistry in the Psychopharmacology, Drug Misuse and Novel Psychoactive Substances Research Unit at the University of Hertfordshire, says there is a “plethora” of new and untested chemically diverse psychoactive substances on which only limited pharmacological testing, if any, is carried out.

“[These may be] resurged molecules, including failed patents, known substances used in novel ways — novel routes of administration, novel forms, for example, nasal sprays, [e-cigarette] liquids — or completely new drugs we’ve never heard of before, with unpredictable and unknown adverse effects.”

The generally untested nature of NPSs adds another layer of complexity to controlling them on the streets, particularly as new groups of users start to emerge.

“We’ve started to see new cohorts among the socially marginalised population — prisoners, the homeless — in addition to existing cohorts, such as students, professionals, people in treatment, men who have sex with men, the unemployed,” explains Guirguis. “It’s not confined to one, so it’s not easy to track or define.”

We’ve started to see new cohorts among the socially marginalised population — prisoners, the homeless — in addition to existing cohorts, such as students, professionals, people in treatment, men who have sex with men, the unemployed

Who is using novel psychoactive substances?

Use of synthetic cannabinoids among prisoners is of particular concern. A survey conducted in UK prisons in 2016 found that 33% of the 625 inmates who responded reported using Spice within the previous month, in comparison to 14% who reported cannabis use in the previous month[6]

.

According to the Home Office review, NPS use in prisons has continued, or in some cases increased, since the PSA came into force — as have associated violence and health harms[3]

.

Stevens explains that prisoners are able to get hold of the drugs in several ways.

“They are smuggled in by staff or visitors. There has also been a move from smuggling it in herbal material to sending it in soaked in paper. People cut up the little bits of paper and smoke them in joints — it’s very hard to keep these substances out of prison.”

Source: Courtesy of Roz Gittins

Roz Gittins, director of pharmacy for Addaction, a national charity that provides a range of services to help support people affected by drug and alcohol problems, says that pharmacists have a role in directing NPS users towards specialist services

Roz Gittins, director of pharmacy for Addaction, a national charity that provides a range of services to help support people affected by drug and alcohol problems, sees the impact of NPS use on a daily basis.

Very often people aren’t only using NPSs, they’re using additional, maybe more traditional, substances that we’d think of, like heroin, on top

“Very often people aren’t only using NPSs, they’re using additional, maybe more traditional, substances that we’d think of, like heroin, on top. Sometimes they choose to displace them and use one over another, while others may be presenting purely for problems with NPSs alone.”

Gittins says that one of the biggest challenges is identifying what someone has taken.

“If someone says they’re using Spice, unless they’ve gone off and got it tested there is no guarantee that that is truly what they’ve taken.”

She adds that pharmacists have a role in directing NPS users towards specialist services.

“If someone presents, for example in community pharmacy, saying that they’re experiencing problems with these substances, then [pharmacists] need to signpost appropriately, and that includes specialist substance misuse treatment services [like Addaction] as well.”

If someone presents, for example in community pharmacy, saying that they’re experiencing problems with these substances, then pharmacists need to signpost appropriately, and that includes specialist substance misuse treatment services like Addaction as well

The Psychoactive Substances Act

Despite the current focus on the harms associated with NPS use, some experts, including David Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College, London, have highlighted that, compared with traditional drugs of misuse, the death rate associated with NPSs is low.

In a blog posted prior to the PSA coming into force, Nutt said that protagonists for the PSA had exaggerated the number of deaths and that the actual number in 2014 was “about five”[8]

.

Two years on, Nutt maintains that “NPSs, as properly defined (i.e. those captured by the PSA not the MDA 1971), pose little health threat”.

“The number of deaths is small in relation to other drugs,” agrees Stevens.

“The big public health crisis at the moment is not Spice, it’s heroin. There are thousands of people dying every year from heroin, the number of people dying from NPSs is in the tens,” he explains.

The big public health crisis at the moment is not Spice, it’s heroin. There are thousands of people dying every year from heroin, the number of people dying from NPSs is in the tens

“Obviously those are tragic deaths that something needs to be done about but, compared with the total inaction, or almost complete inaction, of the government on heroin, there’s been a complete overreaction on NPSs.”

Stevens adds that before the PSA was introduced, the government reported that there had been at least 68 NPS-related deaths recorded by the National Programme on Substance Abuse Deaths in 2012. However, many of the substances that caused these deaths were already controlled under the MDA 1971.

“The number of deaths related to substances that were newly controlled by the PSA (i.e. NPSs) was even smaller than that,” he explains.

This oversight was highlighted in a letter to The Lancet written by Nutt and his colleague Leslie King, on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, in 2014[9]

.

“There is thus no simple answer to how many deaths were associated, let alone caused, by new psychoactive substances or even legal highs in any given period,” they wrote.

However, it seems the PSA has been effective in tackling the problem of NPSs on the surface. The Home Office review found there had been a considerable reduction in NPS use among the general adult population since the PSA, mainly driven by a reduction in use among those aged 16–24 years.

The review includes data from police forces, which suggest that the PSA has led to head shops either closing down or no longer selling NPSs, with 332 retailers identified as having ceased the sale of these substances. Anecdotal feedback from police forces also confirms that the open sale of NPSs has ceased since the introduction of the PSA, it says.

“The Act has been successful in closing down the head shops — there are no longer places you can go to buy Spice or synthetic stimulants,” says Stevens.

The Act has been successful in closing down the head shops — there are no longer places you can go to buy Spice or synthetic stimulants

A study published in 2017 examined how online shops selling NPSs adhered to UK legislation. It found that, following the PSA, UK-registered websites closed down or moved domain locations and no longer sold to UK customers[10]

.

However, the study also pointed out that it was unknown whether the UK retailers had ceased selling NPSs or had just been displaced to underground markets.

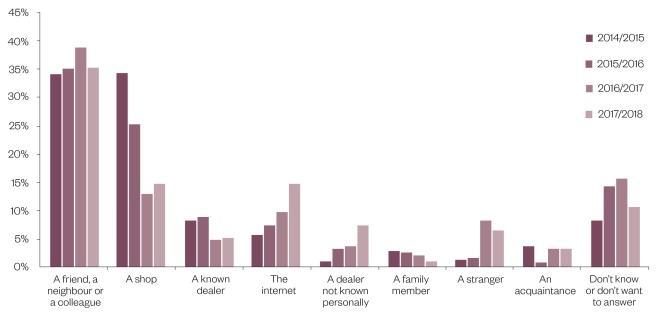

The Home Office review found indications that the PSA had caused the prices of NPSs to increase, and their availability to fall, and discovered a “large-scale shift” away from retailers, with street dealers becoming the main source of NPSs, particularly synthetic cannabinoids (see Figure)[3]

. It also pointed out that there had been an increase in Class A drug use among people aged 16-59 years between 2016/2017 and 2017/2018.

Figure: Sources of novel psychoactive substances used in the past year

Source: Home Office

The Crime Survey for England and Wales provides evidence of a shift away from retail sales of novel psychoactive substances. The survey includes people aged 16–59 years in households across England and Wales, so does not take account of prisoners or homeless people

“The market for street drugs has merged with that of what was formally legal highs. People are getting Spice from the same people they are getting cocaine or heroin from, and that has increased the harms of these substances,” says Stevens.

The market for street drugs has merged with that of what was formally legal highs; people are getting Spice from the same people they are getting cocaine or heroin from, and that has increased the harms of these substances

In 2014, Nutt described the PSA as “arguably the worst piece of legislation in living memory” because of the potential impact it would have in driving users to the black market[8]

.

“Now deaths from cocaine and fentanyl are on the rise because, if everything is illegal, there is no incentive for sellers to go for lower risk products, such as NPSs,” he told The Pharmaceutical Journal.

But Guirguis says the PSA, like any law, is a “rigid instrument” and was never going to be able to deal with such a “multi-faceted problem” overnight.

“There are unsolved problems that the Act didn’t deal with. It’s not [just] a UK problem — it’s global — if anyone had a solution for that overnight they would have done it,” she says.

Guirguis believes the wording of the PSA was purposefully ambiguous in order to include “anything and everything”.

“When they said ‘personal use’, they didn’t quantify that. How can you prove that what I’m possessing is not intended for a later supply and later harm?” she asks. Neither the PSA nor the MDA 1971 quantify personal use.

Guirguis explains that proof of a drug’s psychoactive nature needs to be provided in order to convict someone.

“How can you prove that it is psychoactive?” she asks.

“Your first option is human experience — take the drug in front of me so I can check your mental functioning, emotional state, alertness, consciousness, perception of time and space, mood, behaviour change. Then, when I see these are altered, I can say it is psychoactive. This is not going to happen.”

The alternative is to carry out in vitro (laboratory) testing to measure the pharmacological response to a psychoactive substance, explains Guirguis. But this can be complex, particularly when a substance has been encountered for the first time or when the substance can produce a psychoactive effect that cannot be extrapolated from the existing databank.

In its guidance for prosecutors, the Crown Prosecution Service advises that in vitro tests are not suitable for all types of NPSs[5]

. In these cases, it says, expert witnesses will look to alternative sources of evidence, including published literature. But with most NPSs as yet unidentified, let alone studied, classifying a substance with no reference standard is no easy task.

A further negative impact of the PSA has been on scientific research. “Research is very difficult, as all psychoactive drugs are now in Schedule 1,” explains Nutt.

As a researcher, Guirguis has had first-hand experience of how the PSA has affected progress in NPS research, from work to investigate and identify NPS compounds, to finding antidotes to treat those who have overdosed.

There are so many groups in the UK trying to carry out clinical trials on NPSs … however, when it comes to the Act and the need for expensive licences, it’s not easy

“There are so many groups in the UK trying to carry out clinical trials on NPSs … however, when it comes to the Act and the need for expensive licences, it’s not easy,” she says.

“You can easily break the law due to [the PSA’s] broad wording. You can easily be criminalised when you do the research. The easiest way in many institutions is not to touch it.”

Moving forward

Since its review of the PSA was published in November 2018, the Home Office has admitted that there is more to do.

According to a spokesperson for the Home Office, it has now asked the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs to refresh its advice on the synthetic cannabinoids supplied under the brand name ‘Spice’ and to look into why vulnerable people misuse drugs. However, it has no plans to change the legislation.

But Nutt suggests the PSA be revoked altogether. “Allow safe NPSs, such as methiopropamine and some low-toxicity MDMA analogues, to be sold in head shops to help reduce the influence of the black market,” he says.

In Gittins’s line of work, harm reduction is high on the agenda and she feels strongly that drug checking should be made more widely available for individuals who choose to take NPSs.

“Services like that could reduce those harms. It’s not about saying it’s safe or condoning it but it acknowledges that this is going on, let’s reduce those risks of harm.”

There have been cases where, after testing, people have decided to hand over their supplies to an amnesty bin, saying that they’re not interested in taking it anymore, she adds.

The Loop is one of several organisations that provide drug safety testing, welfare and harm reduction services at nightclubs and festivals. The aim of on-site drug safety testing such as this is to discover trends in the drug market, identify substances of concern that may put users at a greater level of risk, provide an opportunity to engage with hidden and hard-to-reach user populations, and facilitate giving harm reduction information.

“There is a clear rationale to educate people, make them aware of the risks, tell them if they’re going to choose to continue using those substances how they can reduce those risks. But with improved education, you may well see less of it as well,” says Gittins.

There is a clear rationale to educate people, make them aware of the risks, tell them if they’re going to choose to continue using those substances how they can reduce those risks but with improved education, you may well see less of it as well

Guirguis is also in favour of drug testing as a form of education.

“I know it’s controversial but it’s the same as needle exchange. Yes you tell clients that heroin is a harmful substance, we don’t recommend its use and there’s no safe way to use it, but we still say, if you are going to take it, then use clean needles,” she explains.

“And we try to provide them with naloxone kits, convince them to engage with treatment and promote recovery. That’s where we should be going rather than convicting people,” she adds.

Although Martini agrees with the importance of education, he believes that efforts to guide users towards safe use of NPSs could be risky.

“All it does is encourage people to experiment,” he says.

Source: Courtesy of Alex Stevens

Alex Stevens, professor of criminal justice at the University of Kent, who specialises in research on drug policy and the link between drugs and crime, says new legislation has driven the sale of novel psychoactive substances underground

Stevens says the government should focus on why people are using NPSs in the first place.

“In prisons [they] should be focusing on creating regimes of activity and treatment that reduce the demand for drugs, including Spice. Outside of prisons they should be reducing homelessness and providing a wraparound service for people with complex needs, including mental health problems and drug addiction.”

Guirguis emphasises that raising awareness, providing education and the importance of harm reduction and prevention should not be underestimated: “Education and training is needed at every level.”

Panel 2: Resources for pharmacists

- The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s ‘Quick reference guide’, published in April 2018

- The Department of Health and Social Care’s ‘Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines for treatment from substance misuse’ (the ‘Orange Book’), published in July 2017

- Neptune clinical guidelines (endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) and e-modules, published in early 2018

- Medicines, Ethics and Practice 42, published in July 2018

References

[1] Scottish Drugs Forum. A simple (ish) guide to the Psychoactive Substances Act (PSA). 2017. Available at: http://www.sdf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Psychoactive-Substances-Act-2016.pdf (accessed December 2018)

[2] Home Office. Psychoactive Substances Act: Forensic strategy. 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/circular-0042016-psychoactive-substances-act-2016 (accessed December 2018)

[3] Home Office. Review of the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016. 2018. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/756896/Review_of_the_Psychoactive_Substances_Act__2016___web_.pdf (accessed December 2018)

[4] Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Psychoactive Substances Act 2016. Section 2. 2016. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/2/section/1/enacted (accessed December 2018)

[5] Crown Prosecution Service. Psychoactive Substances. 2018. Available at: https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/psychoactive-substances (accessed December 2018)

[6] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. European drug report: trends and developments. 2018. Available at: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/8585/20181816_TDAT18001ENN_PDF.pdf (accessed December 2018)

[7] Marsh S. Huge rise in ambulance callouts to deal with spice users. The Guardian. 20 September 2018. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/sep/20/huge-rise-in-ambulance-callouts-to-deal-with-spice-users (accessed December 2018)

[8] Nutt D. Psychoactive Substances Bill - flawed rationale and huge potential for increase in harms. University of Bath. 2016. Available at: http://blogs.bath.ac.uk/iprblog/2016/02/24/professor-david-nutt-on-psychoactive-substances-bill-flawed-rationale-and-huge-potential-for-increase-in-harms/ (accessed December 2018)

[9] King L & Nutt D, on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. Deaths from “legal highs”: a problem of definitions. Lancet 2014;383(9921):952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60479-7

[10] Wadsworth E, Drummond C & Deluca P. The adherence to UK legislation by online shops selling new psychoactive substances. Drugs: Ed, Preven & Pol 2017;25(1):97–100. doi: 10.1080/09687637.2017.1284417