CORDELIA MOLLOY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

All is not well within the state of Maine. Nestled in the northeastern corner of the United States, it is known for rocky beaches, dense forests and quiet fishing villages. But within this idyll, heroin addiction is rife. Last year, the state saw a 68% increase in the number of deaths due to heroin overdose compared with 2013.

In the past, Maine struggled with a high rate of addiction to prescription opioid painkillers. About three years ago, that all changed.

“It was as if somebody flipped a switch,” says Mark Publicker, an addiction medicine specialist at Mercy Recovery Center in Portland, Maine. “The prescription opioids flipped over to heroin.”

Publicker says heroin suddenly seemed to flood the state, and even people with no history of painkiller abuse started to use the drug. Now more people are treated for heroin than for prescription opioids.

Paul LePage, the governor of Maine, has chosen to confront this public health emergency with an increased focus on law enforcement, while trying to limit addiction treatment. He has proposed defunding methadone programmes, a mainstay for treating opiate addiction, and has imposed a two-year limit on how long a person can be treated with a newer drug, buprenorphine.

“We’re barely scratching the surface in providing effective treatment, and now we’re putting further impediments in the way,” Publicker says.

Despite decades of treatment options, heroin addiction endures. Of the 16.37 million people in the world who have used heroin or other opiates, it is estimated that about one-quarter become dependent on these drugs. In the UK, heroin use has been declining since 2005 but its prevalence is the highest in Europe. In the United States, it is rising sharply as people shift from prescription opioids — abused by about 4.5 million Americans — to cheaper and easier to obtain heroin.

Synthetic opioids such as methadone and buprenorphine, which mimic some of the actions of the poppy-derived opiate heroin, are widely known to stabilise heroin users by ending their drug seeking and to decrease mortality, and both have a place on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. Another drug called naltrexone, and even heroin itself, can also be used to treat addiction. Yet getting treatment to the people who need it remains challenging: only 8% of injecting drug users in the world receives these medicines[1]

. Some heroin abusers are reluctant to be treated, while for those who are willing, treatment implementation is patchy, often reflecting ideology rather than medical evidence.

For example, there is no consensus about what the goals of treating addiction should be, or even about the nature of addiction itself. Some argue that if, by stabilising heroin abusers with methadone or buprenorphine, physicians can set them on a path of productive living, that counts as success. They view addiction as a chronic disease requiring long-term medication, similar to treating diabetes with insulin. Others worry that recovery, meaning complete drug-free living, is an overlooked treatment goal.

“If the goal is abstinence, then everyone is disappointed,” says Richard Mattick of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, who has tracked studies of methadone and buprenorphine around the world. “But if the goal is keeping people alive, stopping them from doing crime, maybe getting them a job, getting them healthier and happier, then methadone and buprenorphine do a pretty good job.”

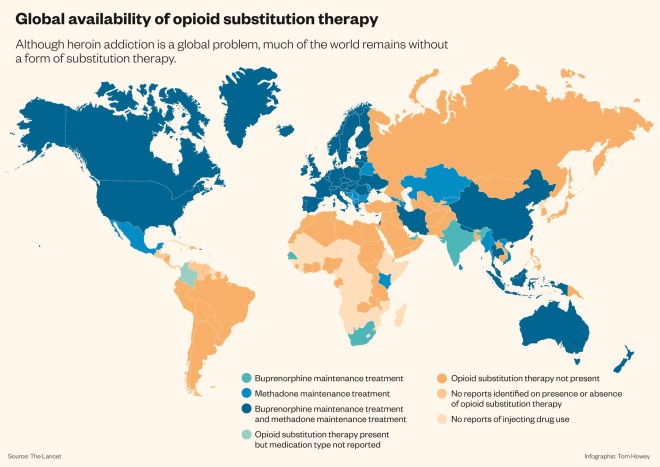

Global availability of opioid substitution therapy

Source: The Lancet

Although heroin addiction is a global problem, much of the world remains without a form of substitution therapy.

Hijacking reward

Heroin targets opioid receptors, which are particularly important for the perception of pain and in the brain’s reward systems. When injected intravenously, heroin swiftly crosses the blood–brain barrier, powerfully stimulating the mu-subtype of opioid receptors to produce intense euphoria.

The heroin high is alluring, but elusive. People become tolerant, requiring higher doses of the drug to achieve the same effect. This not only puts them at risk of death from an overdose, it also leads to a physical dependence on the drug. Without it, regular heroin users descend into the misery of withdrawal, with flu-like symptoms of shaking, sweating, diarrhoea and vomiting. Usually starting within 12 hours of the last dose of heroin, withdrawal drives users to inject again just to feel normal.

Between chasing the high and avoiding withdrawal, heroin users easily fall into addiction. While dependence refers to the physical need for heroin to avoid withdrawal, addiction describes a more turbulent condition in which a person cannot control their habit. Seeking and using the drug becomes their sole purpose, even if it means losing their job, family or home.

But that is not all heroin users stand to lose. The mortality rate in this group is 6 to 20 times higher than that of the general population[2]

. And the problem is getting worse. Globally, the number of deaths related to opioid abuse, including heroin and prescription painkillers, rose by 93% between 1990 and 2013[3]

.Those who inject heroin (which can also be snorted or smoked) are at high risk for blood-borne infectious diseases, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis C.

Yet the nature of addiction does not lend itself to treatment. “Everyone else who has a disease suffers discomfort and wants to get better,” says David Gastfriend, chief executive officer of the Treatment Research Institute, an addiction research and policy centre in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. “But a person with an addiction suffers a magnetic desire to use more of their drug and become sicker.”

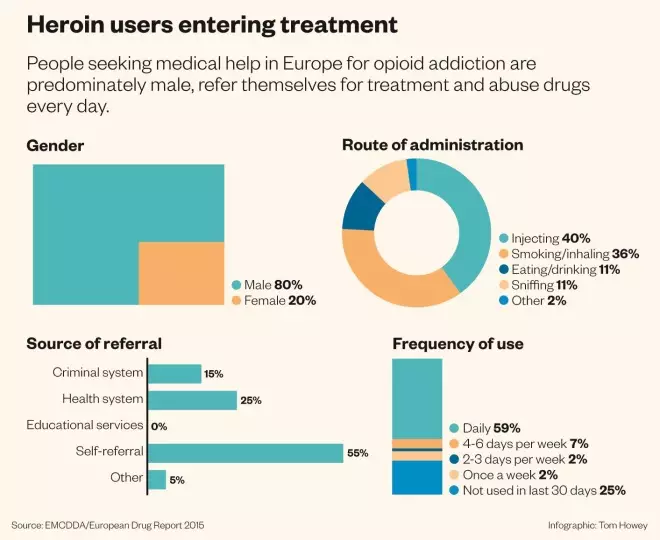

Heroin users entering treatment

Source: EMCDDA / European Drug Report 2015

People seeking medical help in Europe for opioid addiction are predominately male, refer themselves for treatment and abuse drugs every day.

Agonist therapy

Since the 1960s, methadone has become the foundation for treating heroin addiction. Methadone binds to and activates the mu-opioid receptor targeted by heroin. There, the agonist prevents withdrawal and dulls craving, but gives less of a euphoric effect.

Nonetheless, methadone can be intoxicating, and so is typically given out daily at specialised clinics. Despite this inconvenience, people can do well with it: methadone reduces mortality and the crime associated with a life of heroin-seeking, and a meta-analysis found that it decreases use of street heroin and increases time spent in treatment relative to non-drug therapies, including counselling and rehabilitation services[4]

.

“It controls the symptoms so people can feel normal and participate in recovery counselling, and hold down a job, take care of families, and do all the other good things that the rest of us take for granted,” says Peter Friedmann, an addiction medicine physician at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

[Methadone] controls the symptoms so people can feel normal and participate in recovery counselling, and hold down a job and take care of families

But people need to stay on methadone to get these benefits, which fosters the belief that methadone merely trades one addiction for another. Poor-quality clinics, often with limited funding for counselling, reinforce the idea that patients get stuck on methadone, rather than moving on with their recovery. Then there is the fact that people can (and do) overdose on the drug, and that some purposefully use methadone to lower their opiate tolerance, allowing them to get a cheaper high with heroin. These drawbacks sway government policies, most dramatically in Russia, which in 1997 banned methadone, and in 2014 outlawed it in Crimea.

A potentially more appealing medicine, buprenorphine, became available in the 2000s. A partial agonist, buprenorphine activates the mu-opioid receptor less potently than methadone, thus lowering its potential for abuse and overdose. It can be prescribed in a doctor’s office, and patients can take home a month’s worth of pills at a time, thus avoiding the stigma of methadone clinics.

Still, some use it to get high. One formulation, trade-named Suboxone, combines buprenorphine with naloxone, an opioid receptor antagonist, to help prevent misuse: if injected, the naloxone triggers withdrawal.

Buprenorphine can work as well as methadone and is a good option for people who have stable enough lives that they can protect the medicine from misuse by others. But getting patients off it is tough: after a gradual month-long taper of buprenorphine, 70% of participants in one study returned to heroin[5]

.

Doctors are more likely to have success weaning patients off agonist therapies by encouraging them to make substantial changes to their lives and behaviour. These include establishing a drug-free social circle, maintaining employment and other responsibilities, and learning to cope with life’s stresses without using drugs.

The poison as the medicine

Agonist therapy does not work for everyone, with around 5–10% of heroin abusers not responding to methadone or buprenorphine treatment. For these most severe cases, the poison may be the medicine. Several European countries, including the UK, offer pure, pharmaceutical-grade heroin (‘diamorphine’) in supervised clinics as a treatment of last resort. Patients can come two to three times a day to inject themselves, in the presence of a nurse in case of overdose, and to engage in intensive counselling and social services.

This counterintuitive approach has the advantage of engaging users who may otherwise be hard to reach, keeping them in treatment longer and reducing their dependence on illicit drugs and criminal activity. These gains can lay the groundwork for recovery: heroin-assisted therapy was associated with improved social function and mental health in a UK trial, although not to a different extent to the methadone comparison groups, which received similarly intensive counselling and support[6]

.

“Obviously the goal of all treatment would be for someone to become abstinent from drugs, and to live as a fully functioning person in society,” says Nicola Metrebian, a senior researcher at King’s College London who conducted the UK trial, which also found that giving heroin in this context decreased mortality[7]

. “Here we are thinking of stabilisation and harm reduction, but always with that vision of moving people towards those goals.”

Obviously the goal of all treatment would be for someone to become abstinent from drugs, and to live as a fully functioning person in society

In other countries, heroin-assisted therapy is politically radioactive. In the state of Nevada in the United States, a recent bill proposing an increase in taxes to fund addiction treatment, including a pilot of heroin-assisted therapy, did not even make it out of committee for a vote. And despite good outcomes in a trial in Canada, the federal government has refused to provide ongoing heroin treatment to study participants who found benefit from it. Several of the patients are now challenging this in the Canadian Supreme Court. In the meantime, the study researchers are exploring hydromorphone as a similarly effective, less contentious, alternative.

“For people on heroin-assisted treatment, in their mind they are clean because to them heroin is a medication, not a street drug anymore,” says Eugenia Oviedo-Joekes, a researcher at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, who is leading the Canadian trial. “For many people it is the first chance to recover very important aspects of their lives.”

Antagonist alternative

A more politically palatable option may be to block mu-opioid receptors with the antagonist naltrexone. Taking heroin while on naltrexone is a joyless experience, as the high is blocked, and as a treatment strategy it avoids the physical dependence that comes with any opioid receptor agonist. However, it will also throw people who are still on opioids into withdrawal, so anybody taking it needs to be ‘detoxed’ first — a hurdle agonist therapies do not face.

Formulation matters. Daily naltrexone pills work no better than placebo due to poor adherence — each day, people are tempted to skip their pill and get high. Better results come from long-acting monthly injections of extended-release naltrexone, known as Vivitrol: an early study found that it tripled the length of time people abstained from all drugs, doubled the number of people staying in treatment, and halved craving, compared with placebo[8]

. Over 20 studies have produced similar results in a range of patients, including those with alcohol dependence, and Vivitrol is already being used in countries including the United States and Russia.

“Now that the patient isn’t tested on a daily basis, extended-release naltrexone can stabilise early recovery, prevent relapse, and buy time for counselling to take effect and for the patient to initiate lifestyle changes,” says Gastfriend, who previously worked for Alkermes, the company that developed Vivitrol.

Extended-release naltrexone can stabilise early recovery, prevent relapse, and buy time for counselling to take effect

Studies indicate that Vivitrol works at least as well as agonist therapy, and has been associated with 49% lower healthcare costs than methadone[9]

, but head-to-head comparisons in randomised clinical trials are still to be done. Naltrexone might also be useful in shifting patients off long-term agonist therapy, as very low doses may neutralise the cravings associated with discontinuing opioids.

Even though coming off naltrexone does not lead to withdrawal, addicts may resume drug use, with one study of naltrexone implants reporting that about half of patients relapsed once the medication had presumably worn off. A study in alcohol-dependent patients suggests that some protection from relapse may linger, but no clinical guidelines are in place to inform how best to discontinue the drug.

And naltrexone is not necessarily the most attractive treatment option for heroin abusers. It can interfere with pain relief, and some worry that it may dull pleasure from other activities, such as eating, exercise, and sex. Pain can be managed through non-opioid drugs such as paracetamol and aspirin, and there is evidence that naltrexone does not get in the way of everyday pleasures. But heroin addicts considering naltrexone need to be prepared to give up on any possibility of getting high.

“It is a very important treatment, but it’s a niche treatment for the subset of highly motivated patients,” Mattick says.

Going without

Many treatment centres and abstinence-based 12-step programmes see both opioid agonists and antagonists as a barrier to drug-free recovery. Some groups under the umbrella of the self-help organisation Narcotics Anonymous even bar people on opioid replacement therapy from speaking at meetings, although they are welcome to come and listen to the testimonials of others.

However, some drug-free treatment advocates are changing their tune. Facing the epidemic of opioid abuse in the United States, in 2013 Hazelden Betty Ford treatment centres bucked tradition and began to use buprenorphine and naltrexone as adjuncts to their 12-step treatment programmes.

“We recognised things weren’t going well in our setting,” says Marvin Seppala, chief medical officer of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, Center City, Minnesota. Patients were trying to smuggle drugs into treatment centres, and those who completed treatment would too often die of an overdose afterwards.

Now every opioid abuser is offered medicine as part of their treatment. Of those in a long-term residential programme, about equal proportions choose Vivitrol, Suboxone, or nothing. This has resulted in decreases in the death rate after treatment and in the number of people who leave treatment early.

“We feel everything we are doing is making a difference, but the medicines are certainly making a great contribution,” Seppala says, noting that relying on medicines alone is a recipe for relapse.

“If you only use medication as treatment, that ignores the psychological, social, even spiritual aspects of addiction,” he adds. “It’s just as inadequate as saying, ‘Go to meetings and stay sober.’”

If you use medication and that’s all for treatment, that ignores the psychological, social, even spiritual aspects of addiction

In the United Kingdom, where methadone is the first line of treatment and Suboxone use is increasing, policy makers are also beginning to focus on getting people off drugs completely.

“Our concern is that too many users have been parked on methadone for too long, and that treatment has become synonymous with receiving a substitute medication, rather than being a broader process involving a range of rehabilitative services,” says Neil McKeganey of the Centre for Drug Misuse Research in Glasgow, UK. McKeganey has conducted surveys in Scotland showing that heroin abusers wish to become drug free more than many had realised.

Within the past five years, the UK government has encouraged treatment centres to evaluate the progress of those in recovery at regular intervals. However, this does not mean imposing a timetable for cutting off methadone, McKeganey says.

The reorientation also calls for greater investments in high-quality counselling and rehabilitation services, which are more costly and complicated than simply giving out methadone to as many people as possible.

And it shifts the emphasis away from framing addiction as a chronic illness. “The idea that drug addiction was a chronic, relapsing condition underpinned the idea that treatment needed to be long term,” McKeganey says. “We now recognise that there are individuals who do recover, who don’t need life-long medication.”

But commitments to helping addicts recover need to be backed with money. “Rural Maine is impoverished, there are few treatment resources available and poor economic and educational opportunities,” Publicker says. “Often the circumstances to support recovery don’t exist.”

References

[1] Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. The Lancet 2010;375(9719):1014–1028.

[2] Hser YI, Evans E, Grella C et al. Long-term course of opioid addiction. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2015;23(2):76–89.

[3] GBD 2013. Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 2015;385(9963):117–171.

[4] Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J et al. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;8(3):CD002209.

[5] Ling W, Hillhouse M, Domier C et al. Buprenorphine tapering schedule and illicit opioid use. Addiction 2009;104(2):256–265.

[6] Metrebian N, Groshkova T, Hellier J et al. Drug use, health and social outcomes of hard-to-treat heroin addicts receiving supervised injectable opiate treatment: secondary outcomes from the Randomized Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial (RIOTT). Addiction 2015;110(3):479–490.

[7] Strang J, Metrebian N, Lintzeris N et al. Supervised injectable heroin or injectable methadone versus optimised oral methadone as treatment for chronic heroin addicts in England after persistent failure in orthodox treatment (RIOTT): a randomised trial. The Lancet 2010;375(9729):1885–1895.

[8] Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W et al. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. The Lancet 2011;377(9776):1506–1513.

[9] Baser O, Chalk M, Fiellin DA et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of opioid-dependence treatments. American Journal of Managed Care 2011;17(8):S235–S248