Danny Allison

If the sexually transmitted bacterial infection chlamydia is left untreated, it can lead to severe complications, such as ectopic pregnancy and infertility in women, and epididymitis, or testicular pain, in men. Infection rates are high. In England, more than 200,000 new diagnoses of chlamydia were made in 2014[1]

.

For a young person worried they may have contracted a sexually transmitted infection, being able to access testing easily and discreetly is essential. “It’s vital to have different routes to chlamydia testing in the community; simply the more options there are, the more people we are likely to reach,” says Natika Halil, chief executive of the sexual health charity Family Planning Association (FPA).

England has 219 genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics that provide the majority of tests but they are often in towns and cities and not always convenient for rural residents. Community pharmacies have been offering access to screening for chlamydia since 2004, and conducted around 19,000 screening tests in 2012, equivalent to 1% of all tests nationally (although this figure is likely to be an underestimate). Health officials are keen to expand the role of pharmacy in offering testing. As more than 89% of the population live within a 20-minute walk of one of England’s 12,000 pharmacies[2]

, they have the potential to assist in extending coverage across the country.

“Many young people who use pharmacy services would not otherwise access sexual health or GUM clinics,” says Halil. “As many people have asymptomatic chlamydia infections, it can be much harder to engage with people who see no reason to visit a clinic, but who can be reached through other services in the community and can be encouraged to [get tested].”

Jan Clarke, president of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, says: “Pharmacies are very well placed to take a role in sexual health because they are easily accessible, are open extended hours and already have some roles, such as [providing] emergency contraception.” She says it is important to offer patients a range of different access points to sexual health services depending on the level of formal engagement required.

Across England, anyone aged under 25 years can walk into a pharmacy that is taking part in the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) and take home a free test kit. Patients provide contact details so results can be shared, and those with positive results can be invited back to a pharmacy for counselling and offered treatment in areas where this is commissioned. The patient’s GP does not need to be informed unless the patient requests it. Pharmacies also stock other kits – provided for free or for a charge – that only require the patient to have contact with the testing laboratory.

Graham Jones: “I don’t think any other network has the reach that pharmacy does”

Lambourn Pharmacy in West Berkshire offers free chlamydia testing. Owner and independent pharmacist Graham Jones, a local Conservative councillor, is a member of Public Health England’s Pharmacy and Public Health Forum, a group set up in 2011 to provide leadership on public health practice in pharmacy. Jones says it is the informal nature of the screening that makes it work well, particularly for young people. “They’re not having to go in and make an appointment or anything like that. They don’t even need to identify themselves to the staff. It’s completely informal access to that service. It’s made as easy as possible for the patient.”

Pharmacy is in a unique position to offer such services, Jones says. “I don’t think any other network has the reach that pharmacy does. We’re based in the community and on high streets. Increasingly, other medical [services are] provided in health centres, which tend to be larger but further away from communities.”

But the promise shown by this service could be under threat. In England, local authorities gained control of public health budgets in 2013 as part of reforms introduced in the Health and Social Care Act 2012. In June 2015, the government announced that the £3.2bn public health budget would be cut by £200m, or 6.2%, as part of measures to cut overall government spending in the UK. And these cuts are now cemented in the Chancellor’s joint autumn statement and Spending Review, announced on 25 November 2015. Responsibility for public health is devolved in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The decision to cut public health funding provoked a fierce response from health professionals, health charities and local government. Pharmacies and other providers of public health services now face an uncertain few months as they wait to hear whether local authorities in England decide to scale back or withdraw services altogether.

Short memory

On 23 October 2014 — just eight months before the announcement about cuts to public health budgets — NHS chiefs claimed in the ‘Five year forward view’ that a radical upgrade of prevention and public health was needed to protect the future health of millions of children, and ensure the economic prosperity of Britain.

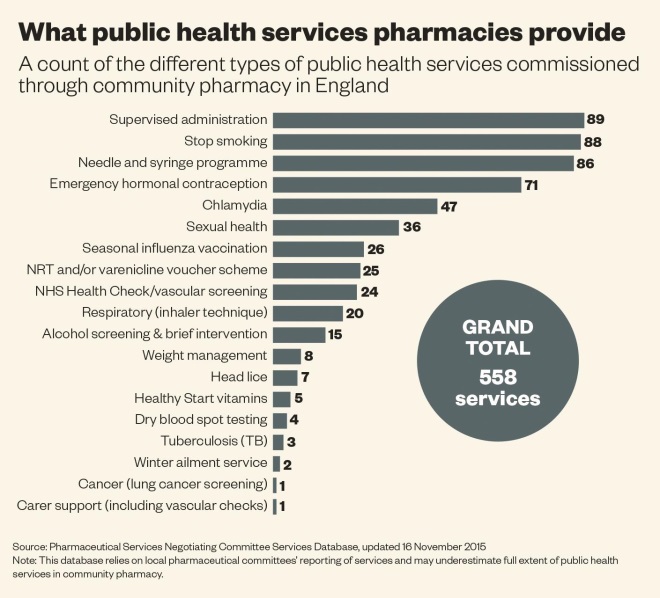

The five-year strategy report focused on the importance of prevention and health promotion. It said pharmacy should have a role in treating minor conditions in the community, as well as providing a range of public health services, from smoking cessation and emergency contraception to needle exchange.

Indeed, later that October morning, health secretary Jeremy Hunt stood in the House of Commons and announced that “the government warmly welcomes the report as a blueprint for the direction of travel needed for the NHS”.

Jonathan McShane: “It’s not the approach if you want to make the NHS sustainable in the long run”

“There’s just no good talking about prevention and then cutting funding for public health,” says Jonathan McShane, a Labour councillor in the east London borough of Hackney, a local authority with relatively high levels of deprivation, and chair of the Pharmacy and Public Health Forum. “It’s not the approach if you want to make the NHS sustainable in the long run and tackle some of these conditions that are amenable to early intervention.”

Local authorities commission around 40–80% of public health services, such as sexual health, public health nursing, drug and alcohol treatment and NHS health checks, through the NHS, according to the Association of Directors of Public Health. The Local Government Association (LGA), which represents councils, says councils will have “no choice” but to reduce funding to these providers. “It will be impossible for these reductions to avoid hitting the NHS,” it says.

In Hackney, the council has written to all local providers of public health services — including pharmacies — saying it cannot guarantee funding beyond April 2016, as the council waits to see what changes it will need to make once budgets have been agreed.

According to the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC), pharmacies elsewhere are already feeling the pinch. Alastair Buxton, the PSNC’s director of NHS Services, says it has heard evidence from “a handful of local pharmaceutical committees who have already seen services such as smoking cessation and minor ailments services decommissioned or cut”.

“If further funding reductions go ahead we would expect to see pharmacy having to work harder to make the case for local services, and funding levels and service targets may be altered,” he adds.

Stitch in time

Nearly 115,000 deaths in England and Wales in 2013, equivalent to 23% of the total, were potentially avoidable through good quality healthcare or public health interventions, according to the Office for National Statistics. Lifestyle diseases are among the leading causes of death, costing the NHS an estimated £5.8bn from illness related to poor diet each year, £900m from physical inactivity, £3.3bn from smoking, a further £3.3bn from alcohol misuse and £5.1bn from obesity[3]

.

Currently, 5.1% of the overall health budget is spent on public health, up from around 4% in 2006–2007[4]

, and public health has been shown to be a good use of national resources.

A study in 2012 by researchers at England’s health watchdog the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) found 85% of 200 public health interventions were considered cost-effective at the threshold NICE uses to assess new drugs[5]

. Many public health interventions were tens of times more cost-effective than drugs it regularly approves.

NICE judges the health benefit of an intervention in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which measure the quality and quantity of healthy life gained. It usually recommends the NHS does not spend more than around £20,000–30,000 per QALY on new treatments.

Smoking cessation interventions led by a pharmacist cost just £546 per QALY on average, and other pharmacy services involving a consultation about the use of nicotine patches are cost-saving. Intensive interviews to address physical inactivity cost just £105 per QALY.

“With pressure on budgets and fundamental changes under way in the NHS and public health structure, there is a need for evidence to support the case for investing in public health interventions,” the study authors write, adding that “given that the cost per QALY for most interventions is extremely low, it seems likely that as a nation we are not investing sufficiently in public health interventions”.

The backlash

Several organisations have expressed concerns over the Department of Health’s consultation on how to implement the savings that will need to be found as part of the funding cuts. The LGA, in a joint submission with the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives and Senior Managers (SOLACE), suggest that even though the cuts were defined as “non-NHS” spending by the Department of Health, they will have a direct effect on NHS funding, since the NHS provides many public health services.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) condemned the cuts to public health funding and has called for the decision to be reversed. “If these cuts fall hardest on the poorest parts of the country they will widen health inequalities,” the RPS’s English Pharmacy Board said in its official consultation response.

John Ashton: “Everything that public health funds touch is potentially vulnerable”

Since the transfer of public health from primary care trusts, public health teams have been reduced in size and public health money is being used to “prop up” many other local authorities’ functions that are also experiencing reductions in funding, says John Ashton, president of the Faculty of Public Health, a charitable association that sets standards for specialists in public health in the UK.

Many different services could be at risk but there is particular concern about sexual health services and smoking cessation programmes. “Everything that public health funds touch is potentially vulnerable,” says Ashton. “Mental health services, drug treatment services; these are all on the list.”

The impact on pharmacy may not simply be confined to reduced or withdrawn services, however. “In recent years there’s been a real effort to understand the extended contribution that pharmacies can make to public health and medicine,” he says. “Unless there’s a real business case from the pharmacy perspective, then the sort of things that have been supported and perhaps co-funded out of public health budgets won’t happen.”

Ashton says that when he was director of public health in Cumbria from 2006 to 2013, he worked with community pharmacies to provide “all sorts of” extended services. “Things that have required a stimulus and impetus from public health teams, are [now] unlikely to happen. It’s the development, the creative stuff, the innovation that will be under threat.”

In Hackney, McShane believes it is too early to know whether pharmacies will lose contracts from local councils, as they are yet to hear the final decision about their allocations — although this is causing significant uncertainty itself. “There will be an impact on community pharmacy as there is on everyone else,” he adds.

Despite some pharmacy services being under threat, there may be new opportunities for pharmacy as councils rethink the allocation of increasingly limited resources. For instance, some may take a more targeted approach to interventions such as the NHS Health Check scheme, says McShane. The period in which services such as this are redesigned will become “crucial” for community pharmacy to explain better what it can do and the evidence for its outcomes.

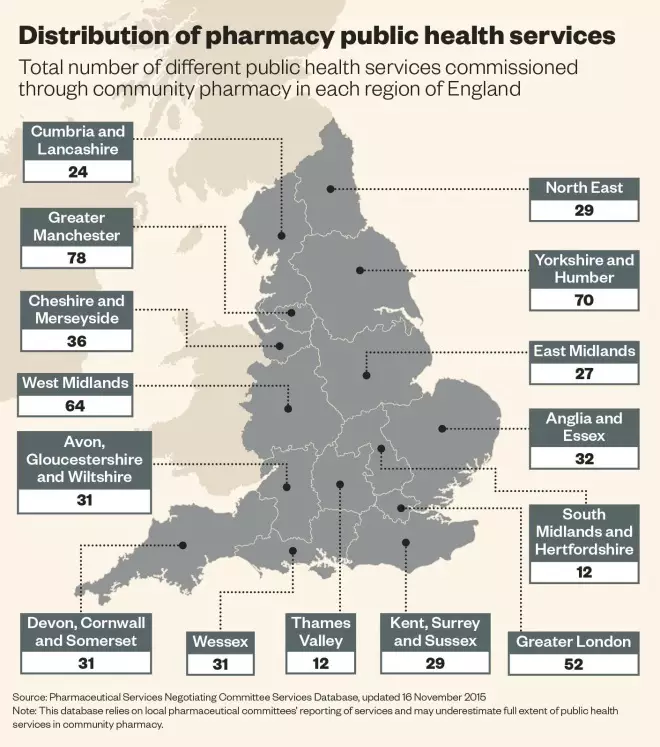

The Pharmacy and Public Health Forum is in the process of mapping services provided by community pharmacy across England, to share “robust” evidence for the added value these bring so that successes can be replicated elsewhere.

McShane encourages pharmacies to embrace the healthy living pharmacy (HLP) initiative — a framework through which a range of public health and promotion schemes can be commissioned by local authorities and clinical commissioning groups. “Getting HLP status is a way of saying we’re ready and equipped and we have the energy and enthusiasm to play a big part in our shared ambitions for our health locally,” he says.

Rob Darracott, chief executive of Pharmacy Voice, which represents several community pharmacy organisations, says new developments such as regional devolution within the UK and the Better Care Fund, which provides financial support for councils and NHS organisations to jointly plan and deliver local services, offer opportunities to integrate health and social care. “One would hope that community pharmacy representatives locally would want to continue to have conversations about how having the [pharmacy] networks in all neighbourhoods is a fantastic resource.”

Once the allocations are revealed, Darracott says, “we need pharmacy at local level to be relatively flexible and recognise the challenges faced by local government in their area”.

Public Health England’s chief executive Duncan Selbie said in a statement that while the cut to funding would be a “difficult ask” of local government, “they are best placed to manage and prioritise resources and I am confident they will, with the least possible impact”. The Department of Health acknowledges that difficult decisions need to be made to reduce government spending. “Local authorities have already set an excellent example of how more can be done for less to provide the best value for the taxpayer,” it says.

The full effect of the spending review on public health budgets has yet to be determined. Councils are more anxious about the long-term impact of this than the grant reductions, McShane says. Until the effects are realised, as in Hackney, many councils’ planning for public health in the next financial year will be largely on hold.

Jones believes that pharmacy-led chlamydia services may be more vulnerable to cuts than some other services, such as addiction support. If the service is lost, some young people may be deterred from getting tested, he says. “It’s the informality of access which I think is pharmacy’s great strength.”

References

[1] Public Health England. Infection report. Sexually transmitted infections and chlamydia screening in England, 2014 . June 2015.

[2] Todd A, Copeland A, Husband A et al. The positive pharmacy care law: an area-level analysis of the relationship between community pharmacy distribution, urbanity and social deprivation in England. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005764. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005764

[3] Peter Scarborough P, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe KK et al. The economic burden of ill health due to diet, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol and obesity in the UK: an update to 2006–07 NHS costs. J Public Health 2011;33(4):527–535. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdr033

[4] Butterfield R, John Henderson J & Scott R. Public Health and Prevention Expenditure in England . Health England Report No. 4 2009. Health England.

[5] Owen L, Morgan A, Fischer A et al. The cost-effectiveness of public health interventions. J Public Health 2012;34(1):37–45. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdr075