Olaf Doering / Alamy Stock Photo

Working in academia can allow pharmacists to educate and inspire the next generation of healthcare professionals. Teaching and research-led career progression is possible within universities and other institutions, while pharmacists can still spend more than half their time practising in hospitals, industry or the community. However, these are some requirements and considerations for pharmacists contemplating the transition to academia.

“When people move from the NHS to academia it can be a culture shock because things are less structured so you need self-discipline. It’s not something you do for the money but for the job satisfaction,” says Margaret Culshaw, deputy head of pharmacy at the University of Huddersfield.

Source: Courtesy of Margaret Culshaw

Moving from the NHS to academia is something you do for the job satisfaction, says Margaret Culshaw, deputy head of pharmacy at the University of Huddersfield.

Moving to academia

Culshaw had worked in hospitals for more than 20 years, completing her Masters in healthcare law and teaching a prescribing course at universities part time, before she got her full-time position at Huddersfield.

To work in academia, a pharmacist must have or be working towards a relevant PhD and usually needs to demonstrate why they would be a good teacher. Gillian Hawksworth, a retired lecturer and visiting fellow at the University of Huddersfield, undertook a part-time qualification — a PhD from the University of Bradford — while working in her own community pharmacy in Mirfield, before seeking a position in an academic institution.

“In the 1990s, I was one of the first CPPE [Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education] tutors and, although I loved community pharmacy and I was doing innovative work, I wanted to add training to my portfolio,” she explains. “In 2005 I had the opportunity to go and work at the University of Bradford as a teacher practitioner for three days a week, which was a great experience.”

Roisin O’Hare is the lead teacher practitioner for the Northern Ireland universities network and splits her time between education and clinical work. “My first role in academia was helping the university teach clinical pharmacy more effectively,” she says. “It is hard to balance the split with clinical work because both areas can be busy at the same time.” O’Hare completed her pre-registration training for community pharmacy Moss Chemists in Liverpool, England, before working in the cardiology department at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast.

Pharmacist Kathryn Davison, programme leader for MPharm from the School of Pharmacy, Health and Wellbeing at the University of Sunderland, also divides her time between teaching and practice. She started her career in academia after managing a community pharmacy for 12 years by teaching at Sunderland primary care trust. Her pharmacy-led teaching to care home staff prompted the University of Northumbria to ask her to run a medicines course for nurse prescribers.

Source: Courtesy of Kathryn Davison

Kathryn Davison divides her time between teaching and practice.

After contacting the University of Sunderland to ask if it had any teaching posts available, Davison began running a few community pharmacy sessions and providing ad-hoc classroom support at the university. She studied for the Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) teaching qualification and achieved a Masters in clinical pharmacy.

“I’ve now been at Sunderland for six years and worked my way up to programme leader,” she says. “I still practise and have good relationships with local community pharmacies.”

Mixing clinical practice and teaching

As well as serving as a useful route into academia, teaching and practising pharmacy concurrently has other advantages. O’Hare notes: “If I decided to work in education full time, my experience would not be as relevant and current. Students like to know that your knowledge is up to date.”

Hawksworth agrees. “I was able to teach public health topics,” she says of her time as a teacher practitioner. “To teach well you must be able to talk about your research and provide real-life examples, for instance, around sexual health or smoking cessation.”

Source: Courtesy of Gillian Hawksworth

Gillian Hawksworth says that to teach well you must be able to talk about your research and provide real-life examples.

Natasha Slater is a pharmacy teaching fellow at Kingston University, but is still a regular locum in community pharmacies. She explains: “I decided to move out of community pharmacy when I realised how much I enjoyed the training and professional development aspect of being a pre-registration tutor. I found it rewarding to see my students progress throughout the year, sit their final exam and qualify as pharmacists.”

The qualities and skills of an academic

Slater adds: “You have to be empathetic and supportive to your students and enthusiastic and passionate about the training aspects of pharmacy.”

At the University of Leeds, Theo Raynor, professor of pharmacy practice, has worked in academia for 20 years, having previously spent two decades in hospital pharmacy. “Academia is rewarding but, with league tables and fee-paying students, you must be focused and committed,” he emphasises.

Graham Sewell, head of the School of Health Professions and associate dean at Plymouth University, agrees. “Academia is heavily regulated and the research side is intense. If you come into academia today you must be prepared to up your game in clinical practice,” he says. “Students are clients now and a university is a service provider and gate keeper to quality.”

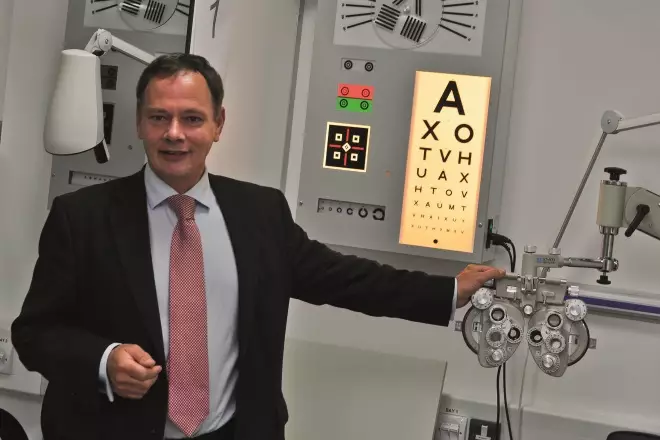

Source: Courtesy of Graham Sewell

Graham Sewell, head of the School of Health Professions and associate dean at Plymouth University, explains that students are clients and universities are service providers.

In addition to conducting research, pharmacists working in academia must be prepared to deliver lectures, seminars, tutorials, practical demonstrations, field work and e-learning programmes, so having strong IT skills is usually important. Additionally, pharmacists may be expected to represent their institution at conferences and other events.

Drawbacks and benefits

Pharmacists moving to academia from other sectors, such as hospitals, community pharmacy or the pharmaceutical industry, may have to accept a lower salary. There is a single pay scale and starting salaries for lecturers are up to £43,000. Additionally, most roles are administration heavy and require constant networking.

However, for Raynor, the attraction was the ability to complete and publish research. He moved into academia after deciding he was a better researcher than he was a pharmacist. His passion is medicines information and he pioneered patient-centred research that improved medicines labelling internationally.

Source: Courtesy of Theo Raynor

For Theo Raynor, the attraction to academia was the ability to complete and publish research.

Sewell believes pharmacists in academia can benefit from having a varied career — he achieved his PhD early to support his career strategy of combining clinical, scientific and technical work. He obtained his first degree in pharmacy from the University of Bath and then underwent pre-registration training with Oxford Hospitals. Returning to Bath, Sewell completed his doctorate then held senior hospital pharmacist positions at Bristol, Exeter and Plymouth, combined with academic appointments of research fellow, lecturer and reader respectively.

As Sewell demonstrates, there are ample opportunities for pharmacists working in academia — individuals can become senior or principal lecturers, readers, professors or deans. O’Hare is actually employed by the Southern Health and Social Care Trust rather than the university and could apply for other jobs within the NHS in future.

Leaving academia

Maria Bell is a pharmaceutical adviser and chief pharmacist at the Department of Health and Social Care on the Isle of Man. She started as a hospital pharmacist in mental health, studied for a Masters and then worked for the armed forces health services charity, SSAFA (Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Families Association), as a pharmaceutical adviser. From here, she went to lecture at the University of Leeds and work as a regional manager for Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE), a provider of educational solutions for the NHS pharmacy workforce across England, in Manchester.

“During five years at CPPE, I became interested in health strategy and economics. The time came to leave academia if I was to remain current”, says Bell.

She says constant networking is crucial if you plan to move from academia back into the NHS. “You need to go to lots of events because you never know who you might meet.”

Bell adds: “I miss the students, but I like the urgency with which we make decisions in my current job. I’m responding to queries from politicians and seeing our work have an immediate impact.”

According to Paul Turner, owner of recruitment consultancy Sterling Cross in Sandwich, England, there are plenty of opportunities for pharmacists working in academia but want to move back into a community, clinical or industrial role.

“There is demand for pharmacists with the communication and planning skills gained and developed within academia,” he says.

Andrew Wise, managing consultant at recruiter Blue Pelican based in Tunbridge Wells, England, says pharmacists moving out of academia can enter medical affairs. “This is a growth area and a diverse discipline where employers want people with deep expertise. There is no selling or marketing, which appeals to pharmacists who have a PhD and want to be involved in detailed discussions about medicines,” he says.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click: