Shutterstock.com

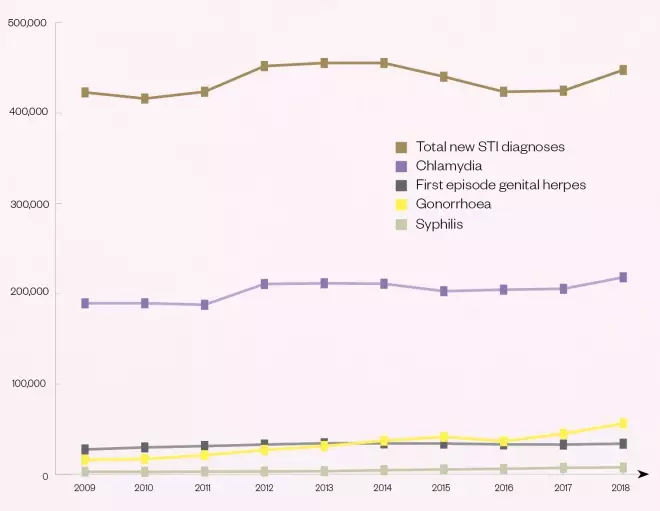

Diagnoses of gonorrhoea in England are at their highest level in more than 40 years, rising 26% between 2017 and 2018. Cases of chlamydia increased by 6% within the same period, syphilis by 5% and first-episode genital herpes by 3% (see Figure)[1]

.

These increases are translating into rocketing demand for sexual health services (SHSs): between 2014 and 2018, consultations in England rose by 15% and the total number of sexual health screenings increased by 22%[1]

.

However, SHSs are struggling to cope. In south London, for example, more than 1,000 patients — half of whom had symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) — were turned away from sexual health clinics over a one-month period in 2017 because they did not have capacity to treat them[2]

.

A similar picture is emerging across the country, with sexual health charities and other non-governmental organisations declaring England’s sexual health system as being “at crisis point”[3]

. And it is not just England that is struggling — in Wales, attendances in sexual health clinics have doubled in the past five years, which has led to considerable pressure on the existing service delivery model[4]

. And, in May 2019, the number of cases of syphilis in Scotland reached 455, a 14% increase on 2017 and the highest since surveillance began in 2002/2003.

In England, many people point to cuts in SHS funding as a cause of this crisis. Between 2013/2014 and 2017/2018, SHS funding has been cut by 14% in real terms[5]

. Advice, prevention and health promotion have been hit particularly hard, with a 35% reduction in funding.

In June 2019, a report published by the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee found “severe” cuts to SHS budgets had meant services were “stripped back” beyond what was needed.

Arrangements fall short of what is needed: funding is insufficient, and commissioning is fragmented

“Arrangements fall short of what is needed: funding is insufficient, and commissioning is fragmented,” concludes the report. “Funding cuts are particularly affecting the ability of providers and commissioners to focus on anything beyond the minimum that is required of them — mandated STI testing and treatment services, and contraception services.”

However, the source of rising cases of STIs is more complex than just money. Public Health England (PHE) says that rising rates could also be attributed to incorrect use of condoms and greater rates of sexual partner change fuelled by the proliferation of dating apps, such as Tinder and Grindr[1]

.

Many of the current challenges with SHSs date back to 2013, when changes introduced via the Health and Social Care Act 2012 led to new arrangements for the commissioning of SHSs in England[6]

.

Figure: Number of new sexually transmitted infections diagnoses in England, 2009–2018

Source: Public Health England[1]

Commissioning arrangements

The new framework saw a shift in commissioning powers from the NHS to local authorities and clinical commissioning groups as part of an overarching government vision for “local leadership for public health”[6]

.

These changes have attracted their fair share of criticism from organisations such as the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare[7]

. Although the bulk of responsibility lies with local authorities, each of the three bodies commission some element of SHSs, with some significant overlap. For example, local authorities are responsible for general contraception, but clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) for contraception for gynaecological purposes. The result has been confusion and additional complexity[6]

.

At a time where sexual health services provided by the NHS are facing cuts … the role of the pharmacist cannot be understated to fill that gap

Addressing this fragmentation may take a long time, but some are suggesting that commissioning community pharmacy to provide better access to sexual health care could have an immediate effect.

In March 2019, PHE published a policy paper to “raise awareness” with commissioners and providers about the “community pharmacy offer” for SHSs[8]

. This paper was the first of its kind and suggested that pharmacists could help alleviate some of the current burdens on the system, not least because of their accessibility to deprived communities and the trusted relationship they enjoy with the local communities they interact with daily.

Trusted member of the healthcare team

This position is backed by other experts. “At a time when sexual health services provided by the NHS are facing cuts and we’re also seeing cuts to local community-based services, the role of the pharmacist cannot be understated to fill that gap,” says Marc Thompson, strategic programme lead for health improvement at the Terrence Higgins Trust.

An enhanced role for pharmacists is necessary to address this “pressing need”, he adds.

“STI screening, particularly for HIV, may be more acceptable to those unwilling to visit specialist sexual health services [and] having local pharmacies as an option for receiving treatment of STIs, particularly with the expansion of postal testing, could provide a convenient option for patients.”

Gareth Kitson, professional development and engagement lead at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, agrees: “There are many reasons pharmacists are well placed to do more,” he says, including their skills and accessibility.

Using the pharmacy to access these services helps to remove the taboo that some people feel

He adds that the “relationship aspect” is also important because pharmacists are often seen as consistent and trusted members of the healthcare team, which is essential when it comes to discussing sexual health.

“People often find it embarrassing to talk about sexual health and would prefer to do this in an informal, but confidential and private manner, with someone they trust,” he says. “Using the pharmacy to access these services helps to remove the taboo that some people feel.”

Some enlightened local authorities are pressing ahead with new pharmacy services in this area. For example, councils in the London boroughs of Southwark, Lambeth and Lewisham have created a network of pharmacies that will provide emergency contraception, sexual health assessments and a condom distribution scheme, which means that any young person with a ‘C-card’ can access condoms free of charge. In Birmingham, pharmacies are providing a range of free services, including chlamydia treatment, condoms, the contraceptive pill and STI self-sampling kits (see Box).

Box: Pharmacy takes on the sexual health challenge

South London

In July 2018, after several sexual health clinics in the area closed as a result of budget cuts, Southwark, Lambeth and Lewisham councils proposed a redesign of the local provision of sexual health services. The redesign proposals were developed in response to increasing rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV and repeat abortions, and involved creating a network of specialised pharmacies from pre-existing pharmacies.

The councils proposed that all of the pharmacies would provide emergency contraception, ongoing contraception, and assessments or referrals for long-acting reversible contraceptives, as well as being ‘C-card’ outlets, which means that any young person with a C-card can access condoms, free of charge. The scheme officially launched in April 2019 and there are now 13 specialised sexual health pharmacies up and running in Southwark, offering all of these services.

“We want to create a pharmacy service that helps people access contraception in a planned way and when they need it most,” says Evelyn Akoto, cabinet member for community safety and public health at Southwark Council.

Birmingham

Funded by the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (UHB), the Umbrella Sexual Health initiative was set up to reduce stigma, expand prevention and self-care, and create access for previously excluded groups. The work of community pharmacies is a central component of the initiative by increasing access and consequently reducing pressure on sexual health clinics.

Through the £500,000 scheme, a total of 174 pharmacies in the area now provide a range of free services under either tier 1 (T1), a relatively basic level of service, or tier 2 (T2), a more comprehensive level of service provision.

T1 includes chlamydia screening, emergency hormonal contraception, condoms and STI self-sampling kits, while T2 includes all of these services plus start-up and continuation of oral contraception, injectable contraception, STI kit initiation, chlamydia treatment and hepatitis B vaccination.

The initiative required the creation of a dedicated training programme for pharmacists, a spokesperson from UHB explains, with face-to-face sessions and online resources provided for free, and some elements needed to be refreshed on a mandatory basis.

“Investing in pharmacy to make overall efficiency savings without compromising standards of care is something many other commissioners might consider,” says Jeff Blankley, chief officer at Birmingham and Solihull Local Pharmaceutical Committee.

Public acceptance of the service has now reached such a level that Umbrella plans to ‘upgrade’ all T1 pharmacies to T2 to ensure that there is a consistent service across all pharmacies.

Of course, the role of pharmacy in sexual health is nothing new. Many pharmacy teams already engage in the provision of sexual health, reproductive health and HIV services, including emergency hormonal contraception (EHC), chlamydia screening and treatment, pregnancy testing, condom distribution and providing information on HIV.

However, there are inconsistencies in the types of services that can be accessed and where. In 2014/2015, less than half (47%) of community pharmacies were being commissioned to provide EHC, according to PHE, 28% to provide chlamydia screening or treatment, and a much smaller proportion commissioned to provide free condoms (9%)[9]

.

To some extent, privately owned pharmacies must continue to exercise discretion as to whether sexual health is a suitable part of their overall offer, points out Thompson.

“It’s down to the willingness of local pharmacies and pharmacists to get onboard with this, thinking about their own capacity to do so. Does it fit with their business model, and are they in areas where there is a prevalence of poor sexual health?”

If pharmacies are in a rural area with an older population and a low prevalence of STIs, he says, it might not be appropriate to take up that training and development.

“Whereas if in a large urban area where there is a high prevalence of, say, chlamydia in young people, it would be highly appropriate for them to step in and provide additional services.”

Sexual health is multifaceted and, in many cases, requires specialist medical expertise, equipment or resources. As a result, careful consideration will need to be given to which services pharmacies are best placed to provide.

The future of pharmacy-based sexual health services

PHE recommends that, with appropriate training, pharmacy teams could deliver sensitive sexual and reproductive health advice, consult on and supply ongoing or emergency contraception, offer pregnancy testing and annual STI screening services, partner notification, as well as encourage onward referral of positive test results to GPs and sexual health clinics. It is still calling on CCGs and local authorities to commission these services, despite their dramatically reduced budgets. However, it defends this call by saying that, in creating a more effective service that prevents more unwanted pregnancies and reduces STI infection rates, large sums of money will be saved.

Pharmacy services should not act as a substitute for traditional services; we would urge the government to reverse the significant cuts .. which are having a damaging effect on patient care

However, Mark Lawton, a consultant in sexual health and HIV and board member for the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, insists that pharmacists should not be viewed as a panacea to slashed sexual health budgets.

“It should not act as a substitute for traditional services. We would urge the government to reverse the significant cuts to public health funding it has made over recent years, which are having a damaging effect on patient care,” he says.

Despite this, experts on all sides appear to agree that pharmacy could act as a crucial addition to the stretched and fragmented network of SHSs currently grappling with severe spikes in STIs and escalating demand.

“Concerns around the time it takes to effectively provide these services and the costs associated are valid, and discussions would need to happen to understand how the pharmacist can be made available to support patients, while the operational aspects of running a pharmacy are still taken care of,” says Kitson.

“However, this should not be seen as an insurmountable problem. This is an exciting and valuable role that pharmacists can play and will give them great opportunities to develop professionally and personally.”

References

[1] Public Health England. 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/806118/hpr1919_stis-ncsp_ann18.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[2] Terrence Higgins Trust. 2018. Available at: https://www.tht.org.uk/our-work/our-campaigns/funding-hiv-and-sexual-health-services (accessed October 2019)

[3] Terrence Higgins Trust. 2018. Available at: https://www.tht.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-11/Public%20health%20and%20sexual%20health%20funding%20updated%20Oct%20FINAL.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[4] Public Health Wales. 2018. Available at: http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/888/A%20Review%20of%20Sexual%20Health%20in%20Wales%20-%20Final%20Report.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[5] Department of Health and Social Care. 2019. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmhealth/1419/report-files/141906.htm (accessed October 2019)

[6] Public Health England. 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/640578/Sexual_health_reproductive_health_and_HIV_a_survey_of_commissioning.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[7] The Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. 2015. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/blogs/examining-the-impact-the-new-health-and-social-care/ (accessed October 2019)

[8] Public Health England. 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/788240/Pharmacy_Offer_for_Sexual_Health.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[9] Public Health England. 2017. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/643520/Pharmacy_a_way_forward_for_public_health.pdf (accessed October 2019)