istockphoto.com

‘Basic bootcamp training’ is how Northern Ireland agency Locate a Locum Now describes the preregistration training year that all graduate students must undergo in order to register as a pharmacist.

On the other hand, Tim Roberts, professional development manager for the Queensland branch of the Pharmacy Guild of Australia, prefers to think of its internship programme as a “safety net” to support the transition from pharmacy student to registered pharmacist. And researchers report that Sweden’s six-month advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) is seen as a “bridge” between knowledge and practice[1]

.

However you describe it, it is difficult to find anyone on any continent who does not believe in the value of preregistration training, an internship or a traineeship — that is: an extended period, or extended periods, working in a pharmacy under the supervision of a registered pharmacist before the trainee or intern can proceed to registration (known as licensure in some countries).

Angela Cawsey, a pharmacist preceptor (tutor) in Alberta, says the multiple practical placements Canadian pharmacy students must undergo is “critically important”.

“The most valuable part to developing as a new pharmacist is having hands-on experience in practice,” Cawsey says.

A European Union directive (2005/36/EC) stipulates that the minimum training requirement for recognition of a pharmacist’s qualifications must include at least a six-month traineeship. And the International Pharmaceutical Federation’s (FIP) 2013 Global Education Report found that at least 25 out of 94 countries globally (27%) support a post-degree preregistration internship system of 6 to 12 months.

Source: FIP

Luc Besancon, chief executive and general secretary of FIP, says that improvements in pharmacy training and education should be globally driven but based on locally determined needs

Luc Besancon, chief executive and general secretary of FIP, says that improvements in pharmacy training and education should be “globally driven but based on locally determined needs because the expected role of pharmacists can differ greatly from one country to another”.

Slight differences in the details in different countries (and, in several cases, different areas within a country) reveal common question marks over how preregistration training can best serve its purpose across the globe.

Early versus late placements

The 2011 Pharmine study of pharmacy education in the European Union found that, of the 25 member states studied, traineeship began in the fifth year (74%) but some countries, such as Finland, France, Germany, Hungary and Malta, started traineeship earlier — in the first or second year. Cyprus and Luxembourg were excluded because at the time they did not have a full pharmacy degree course.

In countries that follow the more common approach (i.e. training at the end of their university studies), some students believe that earlier practical experience would have been beneficial. Maja Å erÄić, a pharmacy student in Slovenia, says: “It might be good to get [some practical experience earlier] during the course of the studies because it would be easier to connect the knowledge with practical implications.”

Not everyone agrees with this view. Clara Brandt, a pharmacy student in Germany, became frustrated by a first-year placement once she had experienced a later one. “In the last year, interns are allowed to do most tasks in the pharmacy. Therefore I don’t see the necessity of having the four-week internship as part of the [first-year] curricula,” she says.

But research in Finland, following the University of Helsinki’s change from a single, six-month internship at the end of a BSc to a two-part internship system during the second and third year, concluded that there are advantages to earlier integration of the internship experience. Likewise, Canada’s National Association of Pharmacy Regulation Authorities recommends that the country’s requirement for a structured practical training experience should ideally be incorporated into the undergraduate academic programme.

The UK looks set to follow suit, with the NHS’s Modernising Pharmacy Careers Board having recommended, back in 2011, a five-year degree programme integrating two six-month placements, instead of a four-year degree plus preregistration year. Several universities have already embarked on the process of accreditation for new-style course, with the University of Nottingham advertising its 2016-entry, five-year integrated MPharm as “groundbreaking”.

The issue of multiple shorter placements rather than one longer one raises the question: “How much time should preregistration trainees spend in practical training?” Perhaps because of the perceived benefits, some believe that a longer training period would be ideal.

“My placements were often not long enough,” says Dan Burton, pharmacy student and vice president of professional affairs for the Canadian Association of Pharmacy Students and Interns. “I found I learnt so much more while on rotation. You can finally put all the pieces together and see how real life practice actually works.

“However, we only get such limited time on rotation then we have to go back to the classroom. The more time I could spend with a preceptor or someone guiding me prior to entering into practice the more confident I would become before stepping into the profession.”

Sectors of practice

Multiple shorter placements spread throughout study years give pharmacy students the opportunity to gain practical experience in different areas of practice.

UK pharmacist Will Farmer, for example, believes he “missed the boat a bit” in terms of completing hospital training, despite a two-week placement as part of buying group Numark’s preregistration training programme. Urvi Shah, a preregistration trainee at Green Light Pharmacy in London, would also like “some insight” into hospital and pharmaceutical industry practice. Shah’s tutor, Salsabeel Al Ansari, agrees that the UK’s preregistration training should “incorporate more time in different industries… so you don’t get pigeonholed into one place depending on where you have done your preregistration [placement]”.

In the UK, there are more than twice as many community preregistration places available than any other type, and this is echoed in other countries, even those that mandate multiple placements. For example, a trainee in Germany must do either two community placements or one community placement and a hospital or industry placement. But Brandt does not understand why she has to complete so much community training when she does not plan to work in the sector. “I would like to have less mandatory internships in community pharmacy, because it decreases the motivation [for the training],” she says.

What is lacking is my contact with other fields in which pharmacists can practice, such as regulatory affairs, pharmacovigilance or others

In Australia, researchers found that interns were not prepared for hospital practice, which they attributed to a lack of opportunities for practical training in the sector[2]

. Raluca Radu found the same as a pharmacy student in Romania. “The only placement I was dissatisfied about was the one in hospital pharmacy because it is underdeveloped in Romania and I did not have that many activities to do.

“I would like the university to be more involved in finding placements for students, especially in areas outside community pharmacy, which are hard to access on your own.” And it is not just a case of community versus hospital, says Radu: “What is lacking is my contact with other fields in which pharmacists can practice, such as regulatory affairs, pharmacovigilance or others.”

Addressing the lack of mixed sector training is one target of changes to pharmacy education in Ireland, where an integrated MPharm replaced a four-plus-one model last September. Boots Ireland teacher practitioner Paula Reilly, based at University College Cork, explains: “This will mean that the current preregistration year will no longer exist and placements will instead be dispersed throughout years two, three, four and five. The aim of this is to expose students to all sectors of pharmacy (community, hospital, industry, regulatory).”

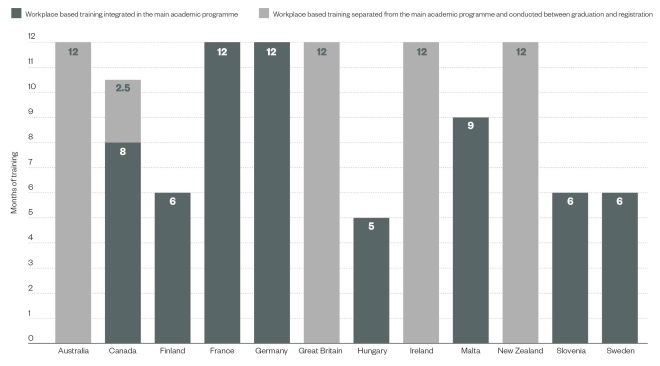

Figure 1: Time spent in practical pharmacy training in selected countries worldwide

Source: FIP

Trainees in most countries complete formal practical training either as part of the main academic programme or separate to it, whereas trainees in Canada complete both types of training

Reflecting pharmacy practice

The changes in pharmacy education in Ireland are also aimed at reflecting huge changes to pharmacists’ roles, says Reilly: “Ten years ago the role of the pharmacist was focused on the task of dispensing, whereas today it is all about patient-centred care and providing services to patients.”

This change is recognised in several parts of the world. In its 2014 Global Framework for Quality Assurance of Pharmacy Education, FIP says: “Many countries are undergoing (or planning to undergo) major transformation of pharmacy education. They are examining the roles and responsibilities that pharmacists can and should have in the delivery of healthcare services, and articulating the competencies that are required to perform these roles and responsibilities effectively.

“They are considering what levels, models, and duration of education and training are needed to ensure that pharmacists achieve these competencies before entering practice.”

It certainly keeps training providers on their toes, says Roberts, from the Pharmacy Guild of Australia: “Because our industry is so dynamic and the practice of pharmacy is ever evolving, the challenge to internship training providers is to remain relevant and in touch with contemporary pharmacy practice. The content covered in our course is constantly under review, ensuring that any changes to practice (or new areas of practice) are incorporated.”

Hege Amundsen, a pharmacist in Oslo, believes the necessary evolution is already happening. “The practice of pharmacy in Norway has an increasing focus on communication and counselling of patients and other professional healthcare providers, and this trend is partly reflected in the internship system,” she says.

So does Burton, in Canada, where the Canadian Pharmacists’ Association is keeping tabs on how pharmacists are taking on expanded roles and are increasingly being recognised as the medication management experts of the healthcare team. Alberta is the most advanced province in this regard, with 16 areas of practice expansion — from vaccinations to ordering laboratory tests — all enshrined in law.

But there is more to be done. Amundsen adds: “I would like to see more practical assignments in counselling and other pharmaceutical tasks in the internship.”

Incorporating interprofessional learning

One particular area crying out for development is inclusion of interprofessional working in preregistration training. As FIP says in its 2015 Global Report Interprofessional Education in a Pharmacy Context: “A collaborative practice-ready workforce cannot exist without first establishing effective interprofessional education [IPE]. IPE efforts… should begin before registration or licensing.”

Luke Vrankovich, a pharmacist who says his Pharmacy Guild of Australia internship “definitely delivered”, agrees.

Being able to communicate with other health professionals can only come from experience

“I would like to see more compulsory involvement of interns with other allied health professionals,” he says, and his desire is backed by research. The previously mentioned Australian study[2]

found that 51% of interns “were not prepared for multidisciplinary team care”. And, as one New Zealand intern points out: “Being able to communicate with other health professionals can only come from experience.”

One case study of progress in this area comes from Namibia, where pharmacy and medical students completed tuberculosis clinical rounds together — although the impact of this is still being evaluated.

Changing teaching ahead of changing practice

However, interprofessional working is also an area that highlights the danger of education — in aiming for an ideal — racing ahead of progress in practice, where change can happen more slowly. FIP warns: “If, for example, pharmacy educators have a vision for pharmacy practice and education and implement a model that is not supported by practitioners or regulators, graduates may become disillusioned if the practice or regulatory environment does not allow them to practise in the manner conveyed by the academic programme.”

The issue of pharmacy graduates feeling disillusioned by the lack of opportunity to flex their clinical muscles, particularly in community practice, has been well discussed in the UK. And the same problem exists on the other side of the world, where Australian researchers point out that pharmacists are reluctant to change or expand their scope of practice, and therefore the realities of practice challenge the idealistic professional identities that graduates develop at university. “For example,” they say, “graduates entering an internship in community pharmacy may find that they are required to spend most of their time dispensing. Yet they had anticipated spending more time solving patients’ medication-related problems.”

That the freshly educated can in some ways be ahead of more experienced hands perhaps explains why tutors all over the world are quick to point out that one of the advantages of preregistration training is that the people who support it also learn from the experience.

Elizabeth Khoury, a pharmacist tutor in Sweden, says that one of the best things about being a tutor is “to learn from students who just got out from the university [because] they have new knowledge”.

Cawsey agrees: “Teaching and working with interns often enhances my own practice; teaching is a great motivator to stay on top of new guidelines and primary literature.”

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists and the European Pharmaceutical Students Association for their support.

References

[1] Wallman A, Sporrong SK, Gustavsson M et al. Swedish students’ and preceptors’ perceptions of what students learn in a six-month advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(10):197. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7510197

[2] Mak VS, March G, Clark A et al. Do South Australian pharmacy interns have the educational and behavioural precursors to meet the objectives of Australia’s health care reform agenda? Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22:366–372. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12090