istockphoto.com

Peer review involves the unbiased, independent critical assessment of scholarly or research manuscripts submitted to journals by key experts or opinion leaders[1]

.

The value of peer review is widely debated[2],[3],[4],[5]

, but is often viewed as measure of a journal’s quality. Although peer review is not without flaws[6]

, it acts as a filter, providing each manuscript with a fair assessment and appraisal by members of the scientific community[7]

. The process is used to determine the suitability of an article for publication, with recommendations and comments from reviewers used by the editor to decide whether to accept the article for publication or reject the manuscript.

Peer review can take place in many forms, with variations between disciplines and journals. The three most common types used by journals in the science and medical field are single-blind (reviewer names are hidden from the author), double-blind (both the author and reviewers are anonymous) and open peer review (author and reviewers are known to each other)[2]

.

Benefits for reviewers

A 2009 survey found that 90% of reviewers agree to take part because they like playing their part as a member of the scientific community and 85% enjoyed reading manuscripts and being able to suggest ways to improve them[8]

. The same survey also found that 91% of researchers believed their last paper was improved by the peer review process[8]

.

Acting as a peer reviewer for a journal allows you to apply your professional expertise to help others improve their manuscripts[1],[9]

and help ensure that the best manuscripts are published within your field. It is also a way of keeping up-to-date with the latest research and developments within your specific areas of interest[1],[9]

.

Reviewing manuscripts can be particularly useful for early career researchers, exposing them to developments within their field of research while allowing them to play a greater role in the research community. Reviewers can learn how to see their own work objectively and can further develop their own research, writing and data presentation skills[10]

.

Participation in the peer review process also allows reviewers to build contacts and relationships with journals and editors, and is therefore a way of improving both their academic and professional profile[9]

.

Reviewers often feel a sense of prestige by being asked to participate in the process[9]

and agree to take part because of its reciprocal nature[11]

— that is, researchers looking to publish their own work would want their article to be peer reviewed and so participate when invited themselves.

Reviewer criteria

Generally, editors will examine the manuscript and seek experts within that particular field of research or those with an aligned interest to provide a review[10]

. Some may use databases such as PubMed[12]

and Web of Science[13]

to identify these individuals or select suitable authors from the reference list in the manuscript.

However, there are no restrictions on who can peer review an article[10]

. Editors do not necessarily confine themselves to always inviting leading academics — the important thing is that reviewers have specific expertise[10]

and are active within the community, either by sitting on expert panels and working groups or by engaging on social media.

Developing knowledge and skills

Most experienced reviewers have learnt how to perform the role through practice[10]

. Some research groups and medical departments hold ‘journal clubs’ to discuss recently published papers, where individuals can develop skills to appraise research papers critically[14]

. When peer reviewing an article for the first time, it may be useful to speak to an experienced reviewer to provide advice or act as a mentor[7]

.

Although most journals tend not to provide formal training for reviewers, they usually provide their own guidance documents for reviewers. Some national and international conferences run specific sessions around peer review. Training days and online courses are also available, but are not compulsory for those wishing to act as a reviewer.

Agreeing to review

Many publishers have databases of contributors and subject experts, and welcome hearing from individuals volunteering to review. If you are interested in participating in the peer review process, you should contact the journal editor, outlining your area of expertise and attaching a current CV (with contact details and affiliations), requesting to be added to their reviewer database. Editors can then contact you should your expertise and research interests match with future submitted manuscripts.

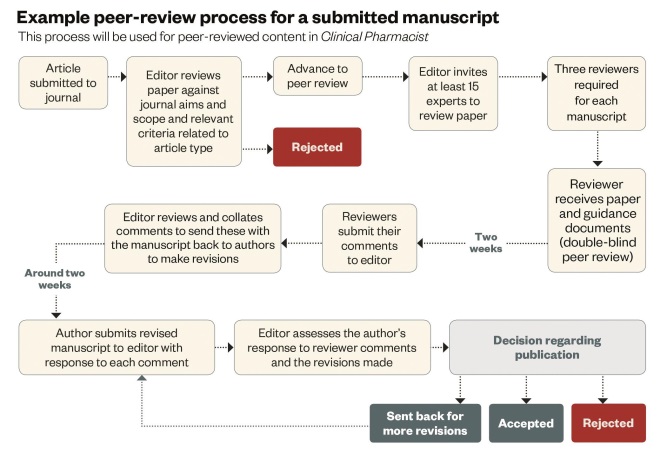

Individuals are usually invited to review by editors directly (see ‘Example peer-review process for a submitted manuscript’). The editor may be aware of your broad expertise and general research interest or specialism, but may not know the specific details of your current work[7]

. You therefore need to decide whether you have the relevant expertise or knowledge to complete a review competently[7],[9],[11]

. If you are in any doubt, you should decline the invitation.

Additionally, if you are thinking of accepting an invitation to review a manuscript, you should consider whether you have the time to review it. Although the time to produce a thorough review varies between manuscripts, it should take three to four hours to complete properly[7]

and reviewers are usually given around two weeks to complete a review. Individuals can participate in the review process regularly, if they have time and have a wide expertise, and can review for more than one journal related to their specialism. If you do not have time to conduct the review, you should notify the editor at the earliest opportunity, so as not to delay the process. Under these circumstances, it is common practice to provide suggestions of suitably qualified alternative reviewers to the editor[11]

.

Lastly, it is important to consider whether you have any conflicts of interest with the work that you are being asked to review. Full details of any potential conflicts of interest, which may be personal, financial, intellectual, professional, political or religious[11]

, should be provided to the editor when you respond to the invitation. The editor can then decide if this would prevent you from providing an unbiased review of the article[7]

. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) has published a useful document that outlines the basic principles to which peer reviewers should adhere and the expectations of the reviewer when being approached to review[11]

, as well as other resources peer reviewers may find useful.

Once you accept an invitation, the editor will usually supply a report form, which gives you direction to help focus your comments when compiling a report.

Writing the report

Once you have received the manuscript and related documents, it is useful to first familiarise yourself with the content published in the journal[9]

.

Reviewers should provide honest and constructive feedback on the manuscript relating to the quality, validity and relevance of the topic to the existing body of literature[1],[9]

. Authors welcome positive feedback as well as constructive criticism. You may not always agree with the opinions of the author that are expressed in the manuscript. However, you should allow these to stand if they are supported and are consistent with the available evidence[11]

.

The following questions are important to keep in mind when reviewing manuscripts:

- Is the manuscript original, topical, interesting and relevant to the journal’s audience?

- Does it help expand the knowledge base in this subject area, thereby contributing significantly to the field?

- Does it build on previous work?

- Is it likely to have an impact on practice or debate?

- Are the methods, analysis and conclusions robust?

- Do the figures and tables make a valuable addition to the article?

- Is the literature adequately addressed? Are the references well integrated and up-to-date with the existing literature?

- Is the manuscript scientifically accurate?

- Is there anything missing that you feel would make the manuscript more complete and comprehensive?

- Does the manuscript mention data that you are unable to access and that would be useful for readers and future researchers?

Once you have read and assessed the quality of the manuscript, you will be asked to make a recommendation regarding publication for the editor. These decisions vary by journal but often include:

- Accept as is — the manuscript is suitable for publication in its present form;

- Minor revision — the manuscript will require light revisions before publication;

- Major revision — the manuscript will require substantial revisions before publication;

- Reject — the paper is not suitable for publication within this journal, or the revisions required are too fundamental for the manuscript to be considered in its current form[1],[7],[9]

.

A section is also usually available in the report for detailed comments. Any comments made in this section should be suitable for transmission to the authors[11]

. Peer reviewers can seek clarification on specific points made in the manuscript and indicate where further elaboration is required. Suggestions on how the author can improve the clarity and the overall presentation of information are valuable and, in some instances, it may be appropriate to comment on whether the subject of the manuscript is interesting enough to justify its length. Reviewers do not need to comment extensively, correct or edit the manuscript regarding grammar or quality of English. However, where the meaning is unclear, this can be highlighted.

Once the review is complete, you can submit it directly to the editor. Some journals require comments to be submitted through an online content management system. However, details would be provided in the original invitation and would be clear from any correspondence you have had with the editor.

Peer reviewers should remember that, throughout the process (including post-review), the manuscripts and correspondence are privileged confidential documents[9],[11]

. If at any time you are thinking of seeking an opinion from a colleague, this should be raised with the editor beforehand[7]

.

After the review

Peer reviewers should respond promptly if the editor contacts them about matters relating to their review and provide any additional information required. Similarly, a reviewer should contact the editor immediately if anything that may affect their comments or recommendations comes to light once their review has been submitted[11]

.

Most reviewers only look over the manuscript once, but some may request that they see the revised version of the manuscript — for example, if certain revisions are deemed necessary or extensive — before publication. In cases where extensive revisions have been made, or if additional data has been included, the editor may request that the original reviewers provide comment on the revised manuscript. Individuals should do their best to accommodate requests from journals to review revisions or resubmissions of manuscripts they have reviewed previously[11]

.

Some experts believe that true scientific peer review begins once a manuscript has been published and journals have processes in place for their readers and the community to submit comments, queries, questions and criticisms on published articles[1]

.

References

[1] International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals (2014). Available at: www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf

[2] Ware M. Publishing Research Consortium Summary Papers 4 (2008). Peer review: benefits, perceptions and alternatives. Available at: www.publishingresearchconsortium.com

[3] Nature’s Peer Review Debate. Available at: www.nature.com/nature/peerreview/debate/

[4] Jennings CG. Quality and value: The true purpose of peer review. Nature 2006. doi:10.1038/nature05032

[5] Novella S. The importance and limitations of peer-review. Science Based Medicine 2008. Available at: www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/the-importance-and-limitations-of-peer-review/

[6] Smith R. Peer review: a flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R Soc Med 2006;99(4):178–182. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.4.178

[7] Elsevier. Reviewers’ Information Pack. Available at: https://www.elsevier.com/reviewers

[8] Sense About Science. Peer review survey 2009. Available at: http://www.senseaboutscience.org/pages/peer-review-survey-2009.html

[9] Jones L. Taylor and Francis Editor Resources. Reviewer guidelines and best practice (2014). Available at: http://editorresources.taylorandfrancisgroup.com/reviewers-guidelines-and-best-practice/

[10] Wilson J on behalf of The Voice of Young Science. Standing up for science 3 – Peer Review: the nuts and bolts, 2012. Available at: http://www.senseaboutscience.org/data/files/resources/99/Peer-review_The-nuts-and-bolts.pdf

[11] Hames I; on behalf of the Committee on Publication Ethics Council. COPE Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers, 2013. Available at: http://publicationethics.org/files/Peer%20review%20guidelines_0.pdf

[12] NCBI. PubMed Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

[13] Thomson Reuters, Web of Science. Available at: https://login.webofknowledge.com/error/Error?PathInfo=%2F&Alias=WOK5&Domain=.webofknowledge.com&Src=IP&RouterURL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.webofknowledge.com%2F&Error=IPError

[14] Esisi M. Journal Clubs. BMJ Careers 2007. Available at: http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=2631