This content was published in 2002. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

A number of challenges for the profession were set out in “Pharmacy in the future — implementing the NHS plan”,1 one of which was the need to embrace new technology. The Audit Commission, in its recent report on medicines management,2 enthusiastically endorsed this suggestion. However, the introduction of automation is not without its difficulties3 and within United Kingdom pharmacy practice automation remains a largely untested innovation. Although others have tried automation,4,5 this has been based on unit doses and proved impractical within the UK health care setting.

It was only with the introduction of “patient packs” that automation became a realistic proposal. Bar codes on original packs are essential for successful automation. Although becoming more widespread, these are still not in standard use across the whole of the pharmaceutical industry. Other potential barriers to implementation include staff attitudes,6,7 particularly among those grades of staff who might see the innovation as a threat to their continued employment.

Despite potential difficulties there is a clear perception that technology is “a good thing” that is likely to be associated with a myriad of benefits, not least a release of scarce pharmacy staff to other, more appropriate duties. However, these benefits were unproven in the UK.

In 1999, we developed a business case for the introduction of automation into the dispensary of a district general hospital. As part of this business case, we identified a number of potential benefits, including reallocation of technical staff to wards to facilitate the re-engineering of medicines supply, and a possible reduction in dispensing errors. In order to justify the subsequent investment, we undertook an evaluation of the implementation of automation, and assessed its impact on performance, staffing requirements and error rates.

Implementation

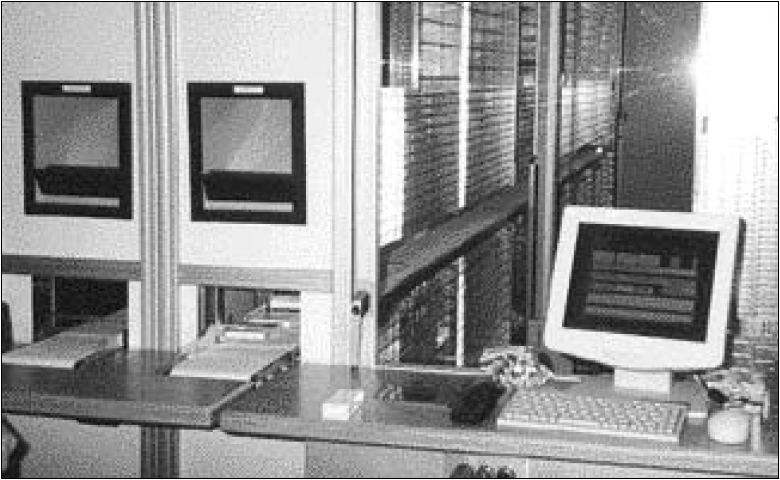

An automated dispensing machine (ROWA speedcase) was installed in the main dispensary at Wirral Hospital at the end of 2000 and “went live” in January 2001. The machine is a tandem system and has the capacity to hold up to 8,000 original packs of drugs in each side while dispensing an average of one item every 20 seconds. Approximately 80 per cent of the dispensary stock is now housed within the speedcase, allowing the dispensary to be redesigned. The speedcase is interfaced with the pharmacy stock control system, JAC, and picks the appropriate pack in response to a “picking message” that is linked to the production of a label.

Before submitting the business case for automation, efforts were made to encourage all pharmacy staff, particularly the technicians, to grasp the benefits to be gained from automation. This involved developing an alternative role for technicians at ward level and including technical staff in the selection process. We visited working sites in Europe and fed back to the rest of the staff during a formal meeting. Technicians were also influential in determining the necessary changes to the design of the dispensary and the changes in workflow that might result from implementation.

The initiation of this plan involved a radical culture change within the pharmacy department and the acknowledgement that current ways of working must be revised in order to obtain real benefit from the innovation. The introduction of automation enjoyed widespread support and indeed without the entire department’s effort it would have proven impossible.

Evaluation

The expected benefits of the system were that it would release technician time to ward-based activities and, based on a historical analysis of dispensing errors, reduce error rates. We also looked for potential problems or effects in other areas. The main variables evaluated were:

- Impact on staff time required for dispensing and availability of technician time at ward level for clinical work

- Impact on the turnaround time for prescriptions

- Impact on error rates within the dispensing process

- Impact on the ordering process as shelf space should be at less of a premium

The benefits of this system were obvious from the first day we went live. By 5pm on day one, we had a dispensary full of staff who had finished early for the first time in years. We had not expected to achieve these benefits so early and therefore had not planned for the redeployment of staff so quickly. This has now been addressed and the amount of time spent at ward level has increased.

The impact of the robot was measured after it had been live for three months.

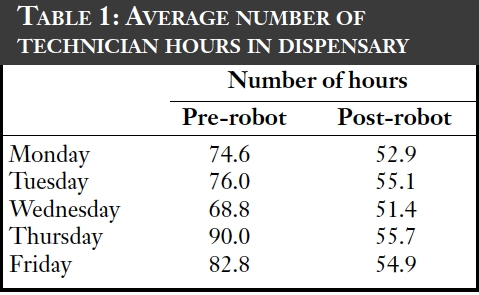

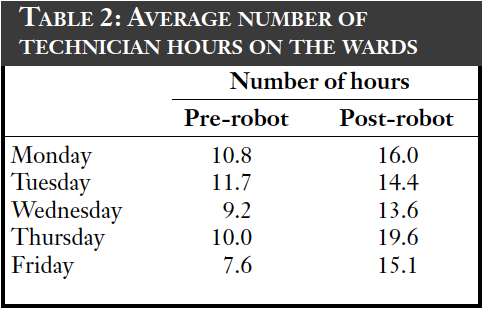

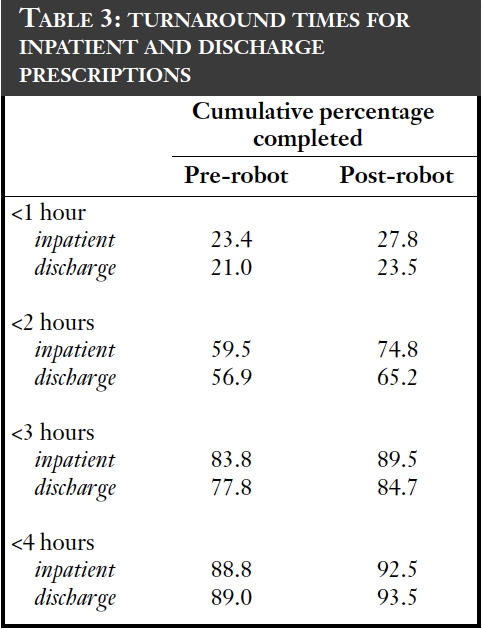

The dispensary handles an average of 38,000 original packs each month. The effect of automation on staff time in the dispensary can been seen in Table 1, with the staff time now available for ward cover in Table 2. In total there has been a redeployment of 3.5 whole time equivalents following the introduction of this technology. Table 3 shows that there has not been any diminution of the service and that turnaround times have improved slightly.

Further reductions in staff time have been seen because less time is needed to order drugs — this has dropped by an average of an hour per day. However, loading of stock into the robot has taken up more time than was envisaged, mainly due to drug deliveries arriving when the dispensary is at its busiest; dispensing from the machine takes precedence at these times.

Other benefits include a reduction in space within the dispensary. We now have 70 per cent less shelving in the dispensary and the occupied floor space has been reduced by half. Up to 80 per cent of the stock is now within the robot.

More importantly, dispensing error rates have fallen: the error rate dropped by 50 per cent for items dispensed in the first four months following introduction of the robot.

Discussion

The machine has now been in operation for over a year and continues to perform well. A desire to maximise its benefits led us to move some dispensing activity from the trust’s second dispensary, which has increased workload on the acute site, without affecting staffing levels or response times.

Other attempts at introducing automation into UK dispensing have fallen foul of the problems of unit dose supplies. This current system depends on the widespread introduction of original pack dispensing. Although strongly endorsed by the Department of Health in its medicines management framework, there are still areas in which primary care colleagues remain unconvinced about the benefits of budget virement. This is surprising because the available information suggests that such an initiative saves money in primary care.

Hospital pharmacy is suffering from a serious staffing crisis. A recent report shows that we are not training sufficient pharmacists or technicians to allow us to address the current shortfall. According to the national hospital pharmacy vacancy survey 2001, there were 247 fewer medical technical officer trainees due to qualify than there were vacancies. Under such circumstances and in the light of the appeal by the Audit Commission for central funding for automation, it would be tragic if primary care colleagues were to derail this initiative due to an inability to facilitate the introduction of original pack dispensing.

Future developments

The machine’s picking head is in use for approximately an hour and half in every 24-hour period. It has 50 per cent of its loading capacity unused. Currently it is not used for picking ward stocks but clearly it could be, given the correct interface with the stock control system. This would bring further benefits to staff workload and reduce errors.

The delivery of drugs into the department is currently undertaken manually with an error rate that could be dramatically reduced by using the bar code technology within the robot and transferring the delivery data to the stock control system (currently a manual process). Discussions are under way to try to develop this. Storage of other drugs is also a possibility. The Home Office has given permission for Controlled Drugs to be stored once robust security software has been included.

In-line labelling and interface to electronic prescribing systems is also at the planning stage, this would reduce the need for any human interaction in the dispensing process, and would be the final cog to allow us to redeploy staff to ward level to practise clinically.

Conclusion

The risk that the trust took in implementing this software has been justified and has reaped more benefits than were originally expected. It has also justified the inclusion of this technology in the “Pharmacy in the future” document.1

The recent report from the Audit Commission, “A spoonful of sugar”2 has explicitly endorsed the introduction of automation. In addition, we have made representation to the Department of Health that the introduction of automation will aid the delivery of targets for reduction in medication errors outlined in “Organisation with a memory”.8

The Audit Commission has specifically recommended that the Department of Health and the National Assembly for Wales commission a specification for automated dispensary systems and consider the provision of earmarked funds to roll out these systems to all hospitals.2

References

- Department of Health. Pharmacy in the Future — Implementing the NHS Plan. London: The Department; 2001. 2

- Audit Commission. A spoonful of sugar — Medicines management in NHS hospitals. London: Audit Commission; 2001. 3

- Rutter PM Brown D, Portlock JC. Can automated dispensing decrease prescription turn-around time and alter staff work patterns? Int J Pharm Prac 2001;9(Suppl):R22.

- Clark C, Chilton NS, Goldberg LA. Automated unit dose drug distribution. Pharm J 1990;244:478–83.

- Boots to trial automated drug distribution system in hospital. Pharm J 1992;249:221.

- Lively BT, Shrader KR. High tech and the human condition: impact on employees. Am Pharm 1986;26:24.

- Crawford SY Grussing PG, Clark TG, Rice JA. Staff attitudes about the use of robots in pharmacy before implementation of a robotic dispensing system. Am J Health-System Pharm 1998;55:1907–14.

- Department of Health. An Organisation with a Memory. London: The Department; 2000.