Science Photo Library / Shutterstock.com / MAG / The Pharmaceutical Journal

David, a carpenter from London, was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) ten years ago. “When my breathing gets bad it feels like my lungs are out of gear,” he says. “It’s like I’m revving and revving, trying harder and harder to breathe, but nothing happens. I get anxious even talking about it. I end up living a sort of half-life where I’m too scared to go out or do anything in case I have an exacerbation.”

David, whose name has been changed, is not alone. An estimated 329 million people around the world — nearly 5% of the population — have COPD, which is a blanket term for conditions that cause breathing difficulties, such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis. In the UK alone, 115,000 people are diagnosed with COPD each year — that’s one diagnosis every 5 minutes. But there are no treatments that can modify disease progression.

This disparity, says Peter Barnes, a respiratory disease researcher at the Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London, is at least in part because the needs of people with COPD are out of gear with the market forces that determine how much money is spent researching the disease.

Source: MAG / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Peter Barnes, respiratory disease researcher at the Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London, says that targeting steroid resistance pathways could salvage some treatment benefit of steroids for COPD patients

“The main problem is [COPD’s] link to smoking, so people consider it self-induced,” Barnes says of people’s seeming reluctance to donate to charities for COPD research. “Also, the risk factors for COPD are closely linked to poverty — cigarette smoking, breathing polluted air, poor diet, poor housing and occupational exposure. The patients are poor and they don’t lobby like patients with, say, heart disease, who tend to be richer.”

The main problem is COPD’s link to smoking, so people consider it self-induced

Another factor, says Barnes, is that whether hamstrung by a lack of funding or not, research into treatments for COPD is difficult. “We don’t know why some smokers develop disease and others don’t,” he says. “Genetic studies haven’t so far been very informative but it’s probably a gene-environment interaction.” Much work is needed to understand the basic pathology of the disease and to look for treatment targets, he says, but researchers also need more short-term solutions to help those who already have it. “One [way] to do that is by blocking the pathway for steroid resistance that we see in COPD patients.”

Getting around steroid resistance

Current treatment for people with COPD is a combination of long-acting beta antagonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), bronchodilators that do not modify the disease course but can relax the small airway smooth muscle and reduce the air trapping that can make people feel breathless. Patients are also given inhaled corticosteroids, anti-inflammatory drugs to target the inflammation that drives much of the disease process.

Inhaled corticosteroids, says Barnes, work well in patients with asthma. They suppress inflammation by de-acetylating the histones that activate inflammatory genes. But in COPD, oxidative stress deactivates histone deacetylase 2, an enzyme necessary for switching off inflammation, thwarting any anti-inflammatory effect of the steroid. “This is why steroids are ineffective in most patients with COPD,” says Barnes.

Oxidative stress switches off the effect of the steroids through several signalling pathways. As such, by targeting these pathways you can reverse the effect and salvage some treatment benefit of steroids for patients. “The idea is being tested but not adequately enough,” says Barnes. He and his colleagues have shown that theophylline — a drug that inhibits phosphoinositide 3-kinase, or PI3 kinase, an enzyme in the steroid-resistance pathway — in combination with steroids is more effective than either drug alone in mice exposed to cigarette smoke[1]

.

However, Barnes says that success with COPD treatment in animals has not been predictive of success in people, probably because of the differing underlying disease mechanisms in humans. Researchers at the University of Aberdeen are testing low-dose theophylline in a randomised controlled trial in 1,424 participants, preliminary findings from which are expected by the end of 2017[2]

. Other trials of theophylline are under way but are at an earlier stage[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8]

.

Theophylline is being tested first because it’s cheap and available but there are other potential drugs

“Theophylline is being tested first because it’s cheap and available,” says Barnes, “but there are other potential drugs.” These include the antidepressant nortriptyline and macrolide antibiotics, both of which increase histone deacetylase-2 activity, but Barnes knows of no ongoing trials of either.

Deepak Deshpande, who researches treatment targets for asthma and COPD at Thomas Jefferson University in Pennsylvania, agrees that drugs to combat steroid resistance in COPD patients are not being tested adequately. “Their potential impact on the disease as a whole is big but for whatever reason they are just not being tested or developed well enough,” he says. “Financial incentive obviously plays a part but, really, until we know more about the disease [and] until we understand the heterogeneity of it better, [it is] a less tempting prospect for drug companies because they’re shooting at target populations they can’t see.”

The problem with clinical trials of drugs for COPD is their cost. You need to follow many patients over at least three years to get clinically relevant outcomes. Barnes estimates that the TORCH (TOwards a Revolution in COPD Health) study[9]

, which tested salmeterol (a LABA) and fluticasone (an inhaled glucocorticoid) in around 6,000 people over three years, cost several hundred million dollars. But the study found no effect on mortality. Such costs are a spectre that looms over any trial of candidate COPD treatments.

“Anti-inflammatory drugs tested so far have been disappointing,” says Barnes. “Clinical trials in COPD are difficult and involve large numbers of patients studied over long time periods.” Barnes adds that there is a risk in developing drugs for COPD because companies have to invest a lot of money before they know whether a drug works. “But if they find one that works they have an opportunity to make a very large amount of money. It may be necessary to be more selective with patients put in trials and to work towards a more personalised treatment approach,” he adds.

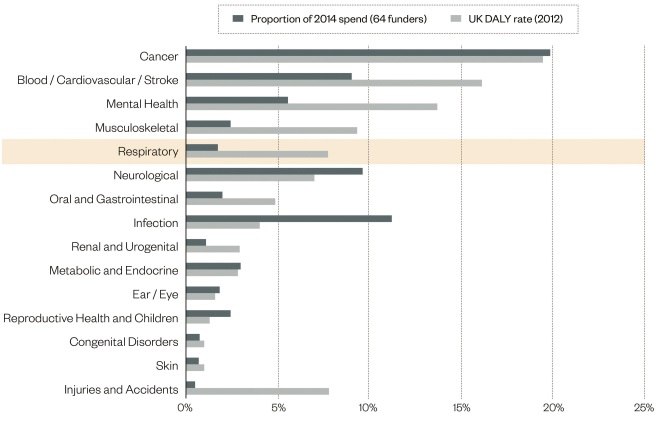

Figure 1: Comparing research funding with disease burden

Source: UK Clinical Research Collaboration 2015. UK health research analysis 2014

Although respiratory disorders account for around 8% of the UK’s disability-adjusted life years, they receive only 2% of research funding

Know thy enemy

To make trials cheaper it would help to test drugs in a smarter way. Testing drugs en masse might mask a real treatment effect in subpopulations of patients; therefore researchers need a better understanding of the disease mechanisms rather than recruiting on clinical phenotype.

COPD is diagnosed spirometrically as a FEV1/FVC (forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity) ratio of less than 0.7. But some patients with COPD have predominantly small airway disease; others have mostly emphysema; and many have a mixture of both. Similarly, some patients have frequent exacerbations while others don’t, and many have a mixture of COPD and asthma, whereas others have one or the other.

The old approach to COPD is to say ‘well this is at least in part an inflammatory disease, so let’s develop anti-inflammatories and see if they work’ — the likelihood that these individual drugs will have a big impact on the disease as a whole is modest

“It think it’s pretty clear that COPD is a heterogenous disorder”, says Prescott Woodruff, a clinical investigator at the University of California in San Francisco. “The old approach to COPD is to say ‘well this is at least in part an inflammatory disease, [so] let’s develop anti-inflammatories and see if they work’. The likelihood that these individual drugs will have a big impact on the disease as a whole is modest.”

Woodruff is one of the lead investigators of the SubPopulations and InteRmediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study (SPIROMICS), a multicentre US study that is prospectively collecting and analysing phenotypic, biomarker, genetic, genomic, and clinical data from patients with COPD. The aim is to identify subpopulations of patients and intermediate outcome measures that might speed up — and thus reduce the cost of — drug trials.

Source: Courtesy of Prescott Woodruff

Prescott Woodruff, a clinical investigator at the University of California in San Francisco, is collecting and analysing phenotypic, biomarker, genetic, genomic and clinical data from patients with COPD, with the aim of identifying subpopulations of patients and intermediate outcome measures that might speed up clinical trials

“We have found that there are subsets of people with different types of inflammation,” says Woodruff. “Type 2 inflammation and interleukin-17-driven inflammation, for example[10]

.” GlaxoSmithKline, he says, is testing mepolizumab in COPD patients with eosinophilia. Mepolizumab is a monoclonal antibody against interleukin-5 and could offer benefits in the subset of patients with primarily type 2 inflammation, driven by the secretion of cytokines such as interleukin-5 by type 2 helper cells.

Other findings presented by the SPIROMICS group at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2016 conference, held in San Francisco, California, on 13–18 May 2016, are that some patients have abnormalities in airway mucin concentration in their sputum samples, and that this mucin secretion is associated with chronic bronchitis and not emphysema[11]

. “It means that some people might have luminal chronic airway disease that involves mucus or poor mucus clearance,” says Woodruff, commenting on the work led by Mehmet Kesimer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

At the ATS 2015 conference, held in Denver, Colorado, on 15–20 May 2015, the SPIROMICS group also presented findings that suggested the value of CT scans to assess disease types. They found that both small airway disease measured by parametric response mapping and vascular abnormalities measured using measurements of pulmonary vascular volume are associated with progression to emphysema[12]

. “It is possible that some people have primarily vascular disease and some have primarily small airway disease, both leading to emphysema,” says Woodruff[13]

. “If you really wanted to prevent emphysema you’d like to know which of those to target.”

Woodruff describes the most surprising finding to come from the SPIROMICS cohort as one published in the New England Journal of Medicine in May 2016: that even smokers who do not have airflow obstruction defined spirometrically can have symptoms consistent with COPD[14]

. “If they do have exacerbations they have an increase in airway mucin concentration — these people are a new clinical subset,” he says of a group of patients they’ve termed ‘smokers with symptoms despite preserved spirometry’. The existence of this subgroup presents a big opportunity. “If these people progress to COPD, if there is a pre-COPD condition, it offers an opportunity for secondary prevention if we can understand what’s driving their disease and treat that.” Based on their power calculations, says Woodruff, the investigators will follow-up these people for five to seven years to assess their outcomes.

Breathing life into COPD research

Further discoveries that sharpen our picture of COPD will be aided by more funding – but this is what COPD and respiratory disorders lack. A report published in 2015 by the UK Clinical Research Collaboration estimated that although respiratory disorders account for around 8% of the country’s disability-adjusted life years — a measure of disease burden — they receive only 2% of research funding[15]

. Neurological disorders, oral and gastrointestinal diseases, infections, and metabolic and endocrine disorders, as well as reproductive health and childbirth-related disease, all receive a greater proportion of funding despite exerting a smaller burden of disease.

Ian Jarrold is head of research at the charity British Lung Foundation, which, he says, funnels between £1m and £1.5m into respiratory disease research each year. “There’s a sense of almost nihilism around COPD,” he says. “People feel that the [lungs are] a difficult thing to study and that [they are] hard to make progress on as quickly as you can in other areas. And we haven’t had any big breakthroughs in a while that could help change that impression.”

Source: Courtesy of Ian Jarrold

Ian Jarrold, head of research at the charity British Lung Foundation, says respiratory diseases lack governmental task forces as seen in other areas, such as dementia and diabetes

The focus on cigarette smoking — though important for public health messaging — is unhelpful for rallying support. It might also be detrimental to the outcomes of non-smokers who develop COPD. “Everyone thought that if you bring down smoking the disease will go away, but we’re learning this is not the case,” Jarrold says, referring to a Canadian forecasting study that predicts a 150% increase in the number of COPD cases from 2010 to 2030, with a 220% increase in people aged 75 years or older[16]

. “We’ve got an ageing population and lung function declines even if you don’t smoke.”

Everyone thought that if you bring down smoking the disease will go away, but we’re learning this is not the case

Jarrold points to a lack of governmental task forces as seen in other areas, such as dementia and diabetes, which could stimulate investment. Other than learning more about the early steps in COPD, he highlights finding a cure as an obvious investment area. “So many people have established disease so we need to find a way to regenerate or repair damaged lungs,” he says. “But that’s of course not easy.” The potential risk of cancer with stem cell therapies added to the already increased risk of lung cancer in people with COPD makes stem cells an unlikely candidate. And the complicated genetic milieu, along with the strong environmental component of the disease, precludes a blockbuster gene therapy.

Drugs aside, he says we need to learn more about maximising the effects of existing therapies, such as exercise. In particular, pulmonary rehabilitation — a defined programme of education and exercise — can help people with advancing disease. “We know pulmonary rehabilitation is useful for people but we also know that it’s not available to all COPD patients in the UK,” says Jarrold. “There are also big questions around the benefits of maintenance exercise after a pulmonary rehabilitation programme — we know the benefits of a programme fade over time and it’s suggested that maintenance exercise would help extend the benefits, but we don’t have research data to prove that.” Until we do, he adds, clinical researchers may not take it seriously and patients could be missing out.

For Jarrold and his colleagues at the British Lung Foundation, there is no question of the glass being half empty. “There’s a feeling that there’s so much to do that it’s hard to know where to start,” he says. “But at the same time there are chinks of light. We just need to make sure we take advantage of them.”

References

[1] To Y, Ito K, Kizawa Y et al. Targeting phosphoinositide-3-kinase-δ with theophylline reverses corticosteroid insensitivity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:897–904. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0937OC

[2] Devereux G, Cotton S, Barnes P et al. Use of low-dose oral theophylline as an adjunct to inhaled corticosteroids in preventing exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:267. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0782-2

[3] The effect on small airways of addition of theophylline as inducer of histone deacilase activity for patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), treated with inhaled steroids and long acting beta agonists. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00893009. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00893009 (accessed November 2016)

[4] Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): clinical study of Symbicort Turbuhaler combined theophylline. Chinese Clinical Trial Registry identifier: ChiCTR-TRC-10000969. Available at: http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=8569 (accessed November 2016)

[5] Efficacy and tolerability study in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients (SECURE2). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01415518. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01415518 (accessed November 2016)

[6] Enhancement of corticosteroid efficacy in COPD. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02340520. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02340520 (accessed November 2016)

[7] Low-dose theophylline as anti-inflammatory enhancer in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ASSET). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01599871. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01599871 (accessed November 2016)

[8] Theophylline and steroids in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) study (TASCS). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02261727. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02261727 (accessed November 2016)

[9] Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, Celli B et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070

[10] Hastie AT, Alexis NE & Doerschuk C. Blood eosinophils poorly correlate with sputum eosinophils, and have few associations with spirometry, clinical and quantitated computed tomography measures compared to sputum eosinophils in the SPIROMICS cohort. American Thoracic Society 2016. Available at: http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2016.193.1_MeetingAbstracts.A6168 (accessed November 2016)

[11] Ford AA, Radicioni G & Cao R. Mucin hypersecretion associated with chronic bronchitis and not emphysema in sputum from COPD patients from the SPIROMICS cohort. American Thoracic Society 2016. Available at: http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2016.193.1_MeetingAbstracts.A3518 (accessed November 2016)

[12] Dougherty T, Iyer KS & Jin D. Total pulmonary vascular volume and one year progression of CT-assessed emphysema in the SPIROMICS cohort. American Thoracic Society 2015. Available at: http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2015.191.1_MeetingAbstracts.A2436 (accessed November 2016)

[13] Boes JL, Hoff BA, Bule M et al. Parametric response mapping monitors temporal changes on lung CT scans in the subpopulations and intermediate outcome measures in COPD Study (SPIROMICS). Acad Radiol 2015;22:186–94. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.08.015

[14] Woodruff PG, Barr RG, Bleecker PHE et al. Clinical significance of symptoms in smokers with preserved pulmonary function. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505971

[15] UK Clinical Research Collaboration 2015. UK health research analysis 2014. Medical Research Council: London; 2015. Available at: http://www.hrcsonline.net/pages/uk-health-research-analysis-2014 (accessed November 2016)

[16] Khakban A, Sin DD, Fitzgerald JM et al. The projected epidemic of COPD hospitalizations over the next 15 years: a population based perspective. Am J Resp and Crit Care Med 2016. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201606-1162PP